The New York Mets in Popular Culture

This article was written by David Krell

This article was published in Fall 2015 Baseball Research Journal

Mets Music

When the New York Mets debuted in 1962, so did a song. More than a sonic icon, “Meet the Mets” is a member of the pantheon of Mets hallmarks occupied by Shea Stadium, Mr. Met, and the mantra “Ya Gotta Believe!” As any devotee of the blue and orange will tell you, “Meet the Mets” attracts Mets fans with a title reflecting the power of alliteration, lyrics infusing the feeling of community, and a horn section blaring the fanfare of excitement. “Meet the Mets” endures in popular culture, demonstrated notably in an episode of Everybody Loves Raymond, an impromptu performance by Bob Costas on Sports Illustrated’s webcast “Jump the Q,” and a revised version in the 1980s.

When the New York Mets debuted in 1962, so did a song. More than a sonic icon, “Meet the Mets” is a member of the pantheon of Mets hallmarks occupied by Shea Stadium, Mr. Met, and the mantra “Ya Gotta Believe!” As any devotee of the blue and orange will tell you, “Meet the Mets” attracts Mets fans with a title reflecting the power of alliteration, lyrics infusing the feeling of community, and a horn section blaring the fanfare of excitement. “Meet the Mets” endures in popular culture, demonstrated notably in an episode of Everybody Loves Raymond, an impromptu performance by Bob Costas on Sports Illustrated’s webcast “Jump the Q,” and a revised version in the 1980s.

When the nascent New York Mets set out to fill the National League void created by the migration of the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants to California after the 1957 season, they faced a Herculean task: to excite, inspire, and motivate baseball fans mourning the loss of two baseball mainstays while creating a unique identity. Rather than ignore the rich National League legacy of New York’s departed teams, the Mets honored it by using Dodger Blue and Giant Orange for their team colors.

When the team announced that it was looking for a theme song, it received 20 submissions. One, called “Meet the Mets,” was the work of the songwriting team of Ruth Roberts and Bill Katz, whose portfolio included “It’s A Beautiful Day for a Ball Game,” “I Love Mickey,” and “Mr. Touchdown, U.S.A.” They actually submitted two versions of the song. According to New York Times sportswriter Leonard Koppett, the entries fell under the scrutiny of Mets president George Weiss, promotion director Julie Adler, and executives of the J. Walter Thompson Advertising Agency. “They submitted one version of ‘Meet the Mets’ to Adler in November in 1961,” wrote Koppett. “Subsequently, they submitted another version to the ad agency. The agency was impressed and called Adler, who was still mulling over some of the other candidates, but was leaning toward the original Roberts-Katz piece.

“Then the agency and Adler compared notes, so to speak, and out of the two versions grew the now familiar work.”1

Glenn Osser created an original arrangement and his orchestra recorded “Meet the Mets” on March 1, 1963. Three years later, “Meet the Mets” entered the musical mainstream when children’s television icon Soupy Sales hosted Hullabaloo, a television show catering to the teenage demographic by showcasing rock and roll groups à la American Bandstand.2

Sales’s sons, Tony and Hunt, performed on the April 4, 1966, broadcast of Hullabaloo with their rock and roll band, Tony and the Tigers. The two sons then joined their father in singing “Meet the Mets” to mark the opening of the 1966 baseball season. It was a curious choice. The song is brassy, like a march. It does not fit into the rock and roll genre, but the Sales family made it work. The Hullabaloo Dancers complemented the Sales men, joining them halfway through the performance.

Additional lyrics reflect the lovable though hapless play of the Mets teams in the early to mid-1960s, describing the Mets as irresponsible, unreliable, and undependable.

Ray Romano used the song as a literary device in the March 1, 1999, episode “Big Shots” of his show Everybody Loves Raymond. Romano’s character, Newsday sports writer Ray Barone, takes his brother Robert to the Baseball Hall of Fame for an event honoring players from the Mets’ 1969 World Series championship team. A devoted Mets fan, Robert names his dog after Art Shamsky. On the car ride to Cooperstown, he points out that Shamsky homered in his first time at bat.

When an announcer introduces the Mets against the backdrop of an instrumental version of “Meet the Mets,” Ray refuses to wait on line to meet Tommie Agee, Jerry Grote, Bud Harrelson, Cleon Jones, Ed Kranepool, Tug McGraw, Ron Swoboda, and Shamsky. He tries to use his journalist’s credentials to avoid the wait. Frustrated by Ray’s arrogance, the Hall of Fame security guards kick out the Barone brothers.

Robert takes the disappointment in stride, but Ray feels shame, anger, and embarrassment because his Newsday affiliation amounted to nil. Ray orders “No talking” on the car trip back to Long Island. Robert acquiesces, humming “Meet the Mets” instead.

Eventually, silence pervades the car. When a local cop stops Ray for speeding, Robert violates the ban on talking by explaining his credentials as a member of the NYPD. It is ineffective—the cop ignores Robert’s status as a fellow law enforcement officer, prompting Robert to experience the same feelings that Ray had endured at the Hall of Fame.

“Meet the Mets” heals the rift. Ray begins singing the Mets’ anthem. Robert joins him, first reluctantly and then joyfully. The scene signifies an unbreakable link among Mets fans, one that has the power to dissolve family tension by instantly recalling a common bond dating back to childhood.

In the mid-1980s, a jazzier version of the Mets’ theme song expanded with new lyrics highlighting the diversity of the geography of Mets fans, mentioning Long Island, New Jersey, Queens, and Brooklyn. Obviously, the song excludes the Bronx—the home of the Yankees has no place in a song about the Mets. A 1990s rap interpretation offered another adaptation.

Koppett decried the lack of traditional arrangement in the song. “There is little in the score of interest to a mid-20th-century audience,” he wrote. “The harmony is traditional; no influences of atonality or polytonality can be found. In fact, it’s sort of un-tonal.

“The melody avoids being square, but is uninspired. The incorporation of folk material (‘East Side, West Side’) in bars 25–28 of the published score is appropriate enough, but not original.

“Nevertheless, if Miss Roberts and Katz have not produced a total success artistically, they should not be blamed nor shown disrespect. The subject is simply too vast. It could be treated with justice only by the mature Mozart, the Mozart of Don Giovanni and the Marriage of Figaro.”3

Mets Movies

One of the Mets’ greatest achievements took place on June 27, 1967—a triple play. Unfortunately, it was fictional. “The triple play, filmed just before the start of the regularly scheduled Mets-Pirates game, was staged for a scene in Paramount Pictures’ The Odd Couple, the film adaptation of Mr. [Neil] Simon’s Broadway comedy about a couple of grass widowers,”4 explained Vincent Canby in the June 28, 1967, edition of the New York Times.

Simon added the Shea Stadium scene and others to give the film version of The Odd Couple an authentic New York City flavor. It highlights the differences between the mismatched roommates, sportswriter Oscar and news writer Felix. During the top of the ninth inning of a Mets-Pirates game, the Pirates trail the Mets by one run with the bases loaded and Bill Mazeroski at bat. Felix calls Oscar in the press box instructions to avoid eating frankfurters as he will be making franks and beans for dinner. During the phone call, Oscar misses Mazeroski hitting into a 5–4–3 triple play.

Canby added, “Before the filming, there was some tension among the Hollywood people, because after setting up their cameras, they had only 35 minutes in which to complete the shot before the start of the game.”5 (The actual Mets-Pirates game that took place on June 27, 1967, resulted in a 5–2 Mets victory.)

When The Odd Couple became a television series, Oscar sometimes wore a Mets cap.

The ’69 Mets formed a plot point in the 2000 movie Frequency, which focuses on an NYPD detective in the present talking to his firefighter dad in 1969. John Sullivan convinces his father, Frank, that their communication is real by explaining certain events of the 1969 World Series.

In a review of the movie for the Los Angeles Times, Michael X. Ferraro explained the inevitability of the Mets’ appearance in movies. “Of course it’s the Mets,” wrote Ferraro. “Who else could it be? It’s no secret that baseball has a certain je ne say hey that Hollywood strives to appropriate whenever possible. But more specifically, when it comes to movie and TV references to the major leagues, the ’69 Mets are the team to use when you’re trying to invoke a sense of wonderment.”

Ferrarro added, “Blessed by the baseball gods, and certainly bolstered by a cadre of New York-born writers and executives, many of whom came of age during the miraculous summer of ’69, the Mets seem destined to live on in the annals of popular entertainment.”6

Characters in the movies The Flamingo Kid and City Slickers wear Mets caps. Similarly, Keeping the Faith and Trainwreck offer homages to the Mets. In the 2005 movie Fever Pitch, Jimmy Fallon plays a Boston Red Sox fanatic who furthers his depression after a romantic breakup by watching the iconic play of Mookie Wilson’s ground ball going through Bill Buckner’s legs in Game Six of the 1986 World Series. As the title “character” in the 1977 movie Oh, God!, George Burns declares, “The last miracle I did was the 1969 Mets. Before that, I think you have to go back to the Red Sea.”7

Mets Television

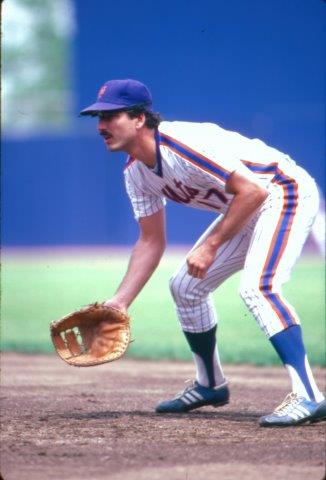

Several episodes of Seinfeld incorporated the Mets into story lines, a result of Jerry Seinfeld being a Mets fan; Seinfeld’s appears in the pilot episode, when the comedic icon declares, “If you know what happened in the Mets game, don’t say anything. I taped it.”8 Keith Hernandez, a key member of the Mets’ 1986 World Series championship team, plays himself in a two-part episode of Seinfeld.9 When Kramer informs Jerry that the Mets play 75 games available only on cable television during the season, Jerry agrees to get illegal cable installed.10 George Costanza pursues an executive position with the Mets, despite having a good front office job with the Yankees.11

Several episodes of Seinfeld incorporated the Mets into story lines, a result of Jerry Seinfeld being a Mets fan; Seinfeld’s appears in the pilot episode, when the comedic icon declares, “If you know what happened in the Mets game, don’t say anything. I taped it.”8 Keith Hernandez, a key member of the Mets’ 1986 World Series championship team, plays himself in a two-part episode of Seinfeld.9 When Kramer informs Jerry that the Mets play 75 games available only on cable television during the season, Jerry agrees to get illegal cable installed.10 George Costanza pursues an executive position with the Mets, despite having a good front office job with the Yankees.11

Seinfeld co-creator Larry David also created the HBO series Curb Your Enthusiasm, a platform for portraying the misadventures of a fictional Larry David. In the episode “Mister Softee,” Bill Buckner guest stars as himself, being a good sport regarding the legendary error in Game Six of the 1986 World Series. Accompanying Larry to a shiva call—a mourning process for Jews—Buckner gets promptly thrown out because one of the mourners is a Red Sox fan who holds a grudge against Buckner.

Buckner becomes a hero when he uses his baseball skills to save a baby. During an apartment building fire, a mother drops her baby from an open window toward the tarpaulin set up by firemen. As the baby bounces from the tarp over the crowd of horrified onlookers, Buckner judges the baby’s trajectory as he would a fly ball and races to protect the baby from hitting the pavement.

A Mets pennant adorns a wall of Lane Pryce’s office on Mad Men. When Pryce hangs himself, Don Draper appropriates the pennant. Who’s the Boss? uses a baseball signed by the 1962 Mets as the focus of a story about the true value of things. Tony Micelli, played by Tony Danza, sells the ball to finance a ski trip for his daughter, Samantha, played by Alyssa Milano. Samantha refuses to let a family heirloom be sold, so she buys the ball back, thanks to some wealthy friends.12

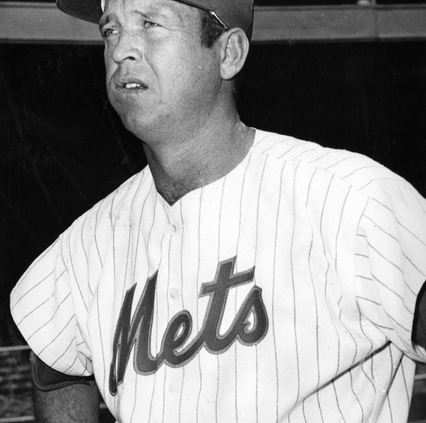

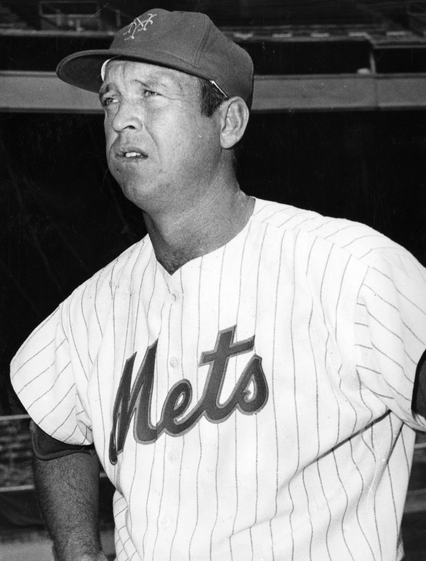

Miller Lite’s popular “Great Taste, Less Filling” television commercials in the 1970s benefit from Mets player “Marvelous” Marv Throneberry, who the Mets acquired on May 9, 1962, and whose mediocrity influences the commercial’s humor: “If I do for Lite what I did for baseball, I’m afraid their sales will go down.” A career .237 hitter beloved by Mets fans, Throneberry played in 116 games for the ’62 Mets, achieved a .244 batting average and notched 87 hits; his career ended the following season, when he played 14 games for the Mets.

Ability, or lack thereof, endeared Throneberry to the denizens of the Polo Grounds in the Mets’ first two seasons, before Shea Stadium’s debut in 1964: “Marv Throneberry, legend has it, was once crestfallen to discover that his birthday cake had been devoured by his Mets teammates before he got a piece—to which Casey Stengel cracked that ‘we wuz gonna give you a piece, Marv, but we wuz afraid you would drop it.’”13

As with Throneberry, it is endearment rather than excellence on the field that has made the Mets endure as a pop culture touchstone.

DAVID KRELL is the author of “Our Bums: The Brooklyn Dodgers in History, Memory and Popular Culture” (McFarland, 2015). David has spoken at SABR’s 19th Century Conference, Negro Leagues Conference, and Annual Convention. He has also spoken at the Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture and Queens Baseball Convention.

Notes

1Leonard Koppett, “For Mets’ Fans: Music to Root By,” The New York Times, May 14, 1963. ↵

2. American Bandstand and Shindig attracted the same audience. Shindig and Hullabaloo each lasted about a year-and-a-half in the mid-1960s, indicative of popular music during the heart of the five-year gap between the Beatles’ American debut on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964 triggering a British invasion of music (e.g., Chad & Jeremy, The Rolling Stones) and the Woodstock concert that emblemized counterculture in 1969. Hullabaloo aired from New York City, alternating between studios in Brooklyn and Manhattan. ↵

3. Ibid. ↵

4. Vincent Canby, “Mazeroski Hits Into Triple Play in ‘Odd Couple Filming at Shea,” The New York Times, June 28, 1967. ↵

5. Ibid. ↵

6. Michael X. Ferraro, “The New York Mets, in the Movies with Startling ‘Frequency,’” Los Angeles Times, May 6, 2000, http://articles.latimes.com/2000/may/06/entertainment/ca-27034. ↵

7. Oh, God!, Warner Brothers, 1977. ↵

8. Pilot, The Seinfeld Chronicles, NBC, July 5, 1989. ↵

9. “The Boyfriend,” Seinfeld, NBC, February 12, 1992. ↵

10.“The Baby Shower,” Seinfeld, NBC, May 16, 1991. ↵

11.“The Millennium,” Seinfeld, NBC, May 1, 1997. ↵

12.“Keeping Up With the Marcis,” Who’s the Boss?, ABC, April 9, 1985. ↵

13.Jason Fry, “Happy Birthday, Jake!,” Faith and Fear in Flushing, June 20, 2015, http://www.faithandfearinflushing.com/2015/06/20/happy-birthday-jake. ↵