May 12, 1866: Atlanta’s first recorded game of base ball

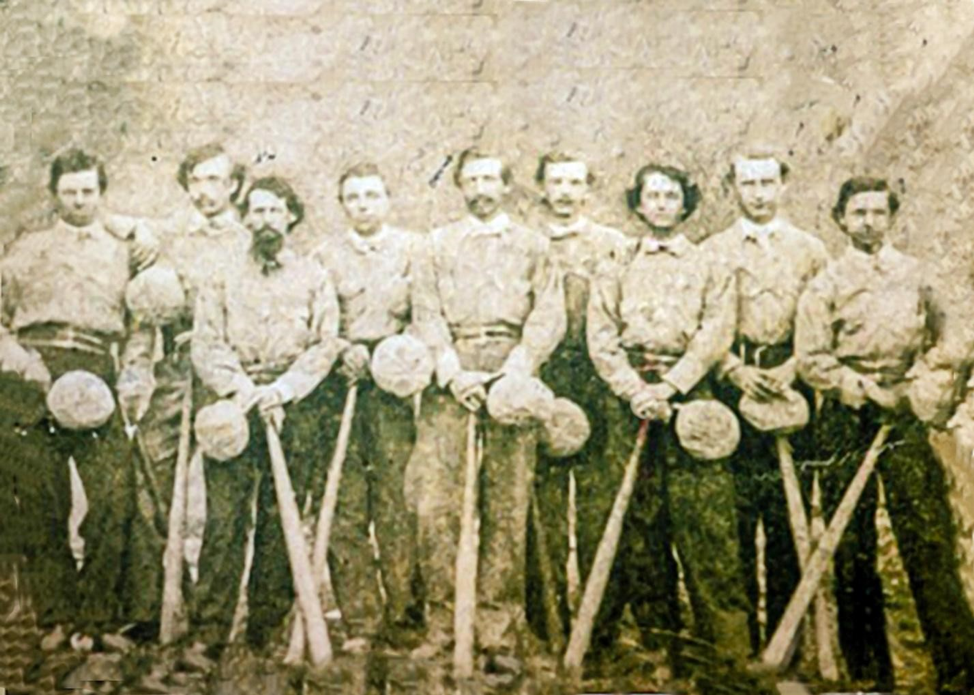

Photo entitled “Famous Gate City Baseball Club of 1867” appeared in Atlanta Constitution, October 21, 1906, page 26. Left to right: Tom Johnson, Hugh Angier, Jim Gregg, Billy Sparks, Bob Dohme, Willis Biggers, George Cassin, Rube Tidwell and John Collier.

In the spring of 1866, a year after the end of the Civil War, Atlanta was in ruins. Lone chimneys served as reminders of where homes and businesses once stood before the city was burned by the Union Army. Red rags hung on doors warned of smallpox quarantine. The city was so poor that its leaders sent pleas to Northern cities for food and money to feed those who had flocked to the once-thriving railroad town that had been so important to the Confederate army.

Amid this chaos, Tom Burnett noticed a lush patch of green grass surrounded by young oak trees near the City Cemetery. Why his thoughts ran to baseball is lost to history, but he decided to organize a baseball team.

Burnett owned an icehouse on Wall Street and likely served as a volunteer fireman, as was common in the 1860s. He quickly gathered friends who were interested in playing baseball. They called themselves the Atlanta Base Ball Club.1 Soon hundreds of enthusiasts went out three afternoons a week to see their husbands, friends, and sweethearts swing the willow stick [bat]; blister their hands catching the ball [no gloves or mitts]; and wear themselves out running the bases.2

After several weeks of enthusiastic practice, team captain Burnett named his starting nine players. Joining him were “Coach” Alexander, Edgar Thompson, Joe Ormond, Smith and Robert Solomon, Sonny Wright, Tiff Meade, Joe Bridges, and Hayne Ellis.3 To celebrate their confidence as a team ready to compete against others, they ordered uniforms. They wore white caps, white flannel shirts, and black broadcloth trousers, held up by wide leather belts trimmed in red.

Robert Dohme, a newcomer to Atlanta who had served in the Union Army, decided to organize his own team. He called it the Gate City Nine. The roster included Dohme as shortstop; James Gregg, pitcher; George Cassin, catcher; John Collier, first base; Willis Biggers, second base; Tom Johnson, third base; Bill Judson, left field; Dick Williford, center field; and Bill Sparks, right field.4

Not to be outdone by the smart uniforms of the Atlanta Baseball Club, they chose light blue knee-length breeches, with crimson stripes down the sides, orange shirts, and highly glazed black military caps. After a few weeks of practice, Dohme decided they were ready to challenge Burnett’s team. The challenge was immediately accepted.

When Tom Burnett and Robert Dohme met to talk about the match game, they settled on May 12, at 2:00 P.M. In need of an umpire, they agreed that Samuel Downs was their best bet. Downs owned the Cabinet Saloon on Alabama Street downtown and was well known as an honest man who never lost his temper and had the respect of both teams.5 Downs studied the Knickerbocker Rule Book and had a large oak chair made to order for the occasion.6 He also arranged for a brass band to lead himself and the two teams onto the field on the day of the game.

So great was the interest in this spectacle that the citizens of Atlanta could talk of little else. Groups gathered on street corners to “discuss the great event and to utter profuse predictions concerning the disastrous defeat that was sure to befall Captain Dohme and his men.”

The day finally arrived. By 10 o’clock people began making their way toward the ball ground near the City Cemetery that would one day be known as Oakland Cemetery. By 2 P.M. the ball ground was surrounded by spectators. Some sat upon carriages, some were in trees and others stood in eager anticipation. Music sounded and a brass band led the teams and Downs onto the field. As the umpire, Downs took his seat in his new solid oak armchair and shouted, “Play Ball!”

And they did. First-hand accounts of the game report that “no one left until the last man in the last inning was declared out.”7

The Gate City Nine had no trouble with Burnett’s soft tosses, delivered underhand in accordance with the rules of 1866. They scored 25 runs in the first inning, often knocking the ball into or over the horses, carriages, and onlookers. By one account, Gate City’s Tom Johnson got the longest hit of the day. It carried so far over the crowd that it was not found until two weeks later – a quarter-mile away.8

It was finally time for the Atlanta Ball Club to swing their bats. Jimmy Gregg pitched, and George Cassin did the catching without a glove, mask, or shin guards. An eyewitness to the game reported, “Gregg pitched a treacherous sphere. … It was a slow twister, which started as if going just where the hitter wanted it and would then fly up under his chin or curl around his feet or zig-zag out into the sociable crowd which surrounded the umpire.”9

Equal praise was given to Cassin, who was described as “a born catcher, he was quick as lightning and active as a cat and would often play right up under the bat. … [H]e could throw to second like a shot out of a shovel.”

After a while, shortstop Dohme and pitcher Gregg exchanged positions and Coach Alexander came to bat for the Atlanta Ball Club. Alexander drilled a soft pitch right back at Dohme, hitting him in the abdomen. “He turned pale as death and fell face-foremost on the ground. Everybody thought that he was dead. Deep groans went up from the crowd. Women screamed and some of them fainted. Children cried aloud.”10 Dohme was revived with some splashes of water and the game continued.

In the end, Sam Downs pronounced the Gate City Nine victorious by a score of 127-29.

The Gate Citys were ecstatic with their victory and had the ceremonial ball covered with gilt and black lettering recording the date, the opponent, and the score. It was placed in exhibition in the downtown Taylor’s Drug Store where people could view it “as if it was some great man lying in state.”

The Atlanta Ball Club was demoralized by the lopsided score and soon disbanded, leaving its beautiful ball ground to the victorious Gate Citys.11 Full of confidence, the Gate City Nine claimed to be the champions of Georgia and would take on any team. Newspaper accounts of the day report that they were victorious in 36 matches before losing to a team of students at the University of Georgia who called themselves the Dixie Club.

Author’s Note

After reading an account of this ballgame in Franklin Garrett’s two-volume history of Atlanta, Atlanta and Environs, I wanted to know if any of the participants in this historic event were buried at Oakland Cemetery, where I served as a volunteer docent. A deep dive into Atlanta history revealed six members of the Gate City Nine (Tom Johnson, Billy Sparks, Bob Dohme, Willis Biggers, George Cassin and John Collier), one member of the Atlanta Ball Club (Joe Ormond) and the umpire (Sam Downs). The research resulted in the creation of a “Boys of Summer” baseball tour that is offered from time to time by the Historic Oakland Foundation. For more information on the Cemetery and the tour: www.oaklandcemetery.com.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Russ Walsh and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Notes

1 Franklin M. Garrett, Atlanta and Environs (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1954), Vol. 1: 12.

2 Augusta Wylie King, “Atlanta’s First Ball Park and First Baseball Team 1866,” Atlanta Historical Bulletin,Vol. 8, No. 32, 1947: 12.

3 King, 13.

4 Garrett, 726.

5 King, 13.

5 Garrett, 726.

6 Smith Clayton, “After 22 Years: The First Match Game of Base Ball in Atlanta,” Atlanta Constitution, May 27, 1888: 5.

7 King, 14.

8 King, 14.

9 Clayton.

10 Clayton. 14 Clayton.

11 Peter Morris, “Gate City Base Ball Club of Atlanta,” in Baseball Pioneers 1850-1870 (Jefferson, North Carolina: MacFarland & Company, 2021), 315.

Additional Stats

Gate City Nine 127

Atlanta Base Ball Club 29

Near City Cemetery

Atlanta, GA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.