J. Lee Richmond’s Remarkable 1879 Season

This article was written by John R. Husman

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was originally published in SABR’s The National Pastime, Winter 1985 (Vol. 4, No. 2).

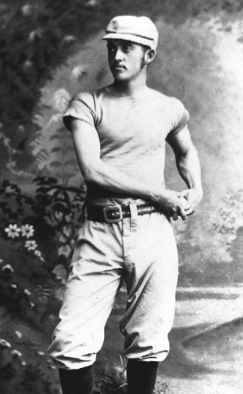

J. Lee Richmond played four full seasons and parts of two others in baseball’s major leagues. Not a long career. Today, more than 100 years later, a check of his statistical record reveals little that would seem to be worthy of recognition. The record does not, however, tell of the spirit he brought to the game and how he changed it. Nor does this record show that he was the first to accomplish the rarest of all single game pitching feats: a perfect game.

J. Lee Richmond played four full seasons and parts of two others in baseball’s major leagues. Not a long career. Today, more than 100 years later, a check of his statistical record reveals little that would seem to be worthy of recognition. The record does not, however, tell of the spirit he brought to the game and how he changed it. Nor does this record show that he was the first to accomplish the rarest of all single game pitching feats: a perfect game.

Richmond burst upon the baseball world in 1879, leading Brown University to the college championship early in that season. He then revived the struggling Worcester, Massachusetts entry in the National Baseball Association so successfully that they were admitted to the National League in 1880. Along the way he played for several teams, as both an amateur and a professional. He ended the season as he began it, playing as an amateur at his alma mater during the fall season. His composite record for the 1879 season may be unparalleled in all of baseball history: a lofty claim, but lending credence are his season total of 47 pitching wins and his official number two ranking among the hitters in the National Baseball Association with a batting average of .368.

Richmond had paid his dues, playing at Oberlin College in his home state of Ohio, for the Rhode Islands of Providence, and two full years at Brown before embarking on this remarkable season. His career in baseball had been lackluster to this point, but the experience he had attained would be the basis for the total baseball player that was about to emerge. Added to this experience was a variety of left-handed curve pitches that he had developed and perfected during the 1878–79 winter in Brown’s gymnasium. In addition, Richmond was named captain of his university’s nine.

The attainment of college baseball’s championship would be the crown on a successful season for most, but it was only the beginning for Richmond. Even before the college season was completed, manager Frank Bancroft of the Worcesters attempted, on more than one occasion, to lure Richmond to his professional team. He sent the young pitcher a barrage of telegrams asking for his services.

PROFESSIONAL DEBUT

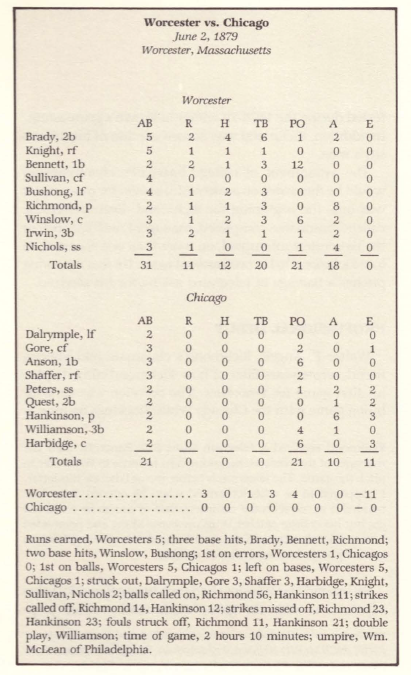

Walter F. Angell, Richmond’s classmate and lifelong friend, wrote years later of how Richmond came to play his first game for Worcester. The occasion was an exhibition game with the Chicago White Stockings on June 2.

Richmond received a telegram from F.C. Bancroft, then the manager of the Worcesters, asking him to come to Worcester to pitch the game. The telegram is before me as I dictate this letter. I happened to be with Richmond when he opened it, and he handed it to me with the comment that of course he could not go, but his college catcher Winslow came along and persuaded him to take chances and change his mind, Winslow agreeing to go along with him and play as catcher.

Richmond and Winslow had each been offered $10 plus expenses to play the game. Richmond resisted jeopardizing his standing at Brown and his reputation on the mound. Chicago was one of the country’s greatest teams, and was hot, having just beaten Boston three in a row. But in the end the arguments of his friend Winslow prevailed. It seems that Winslow was in need of a new pair of trousers, and thus was launched J. Lee Richmond’s professional baseball career!

Anson brought his team to Worcester on June 2 as the leaders of the National League. The Chicagos left Worcester having been shut out 11-0 without having made a single base hit. Richmond had thrown a no-hitter in his first game as a professional! Only three others — Bumpus Jones, Ted Breitenstein, and Bobo Holloman — have done the same in their first start against a major-league nine. This was the first of three exceptional pitching performances he would complete within a nine-day period.

(Click image to enlarge)

Arthur A. Irwin also made his professional debut that day playing third base for Worcester. He went on to play thirteen major league campaigns and to manage eight more. Some 20 years later he recounted the story of that historic game:

I signed a Worcester contract on June 2, 1879, coming to Worcester from my home in Boston, where I had been playing on amateur teams. Although I afterward played shortstop I was sent in to cover third base in that first game. Lee Richmond, the greatest left-handed pitcher this country has ever seen, did the pitching for us, and the game that followed became famous the country over. We had as opponents the Chicago club, and we shut them out by the score of 11–0. Richmond pitched the greatest ball that day I have ever seen in all of my experience. The first Chicago man up reached first on a base on balls, and he was the only one of Anson’s men to see first base during the entire nine innings [author’s note: actually seven innings were played]. Before the game was over the Chicago players were betting cigars against dollars that they would hit the ball, not that they would hit safely, but only hit it.

Richmond had marvelous support by his teammates, not an error being committed — a highly unusual occurrence in that era. His domination was so complete that in addition to eight strikeouts in the seven-inning game not a single ball was hit out of the infield. Both teams wished immediately to get Richmond’s signature on a contract. Worcester was successful, and some 25 years later Bancroft recalled how he had accomplished the signing.

We had struck one of those ruts that comes to every team every once in so often and had lost 18 straight games. The directors were for firing me and getting a new manager. But the stockholders stepped into the breech and saved my life by giving me 30 days in which to either “make good” or lose my job. The next day we were scheduled to play an exhibition with “Pop” Anson’s White Stockings. I had heard of a young fellow with the beautiful name of J. Lee Richmond, with the accent on the Lee, who was doing good work for the Brown University team. I ran down to Providence that night and got the boy to come up to pitch the game against the Chicagos. J. Lee was a slightly built chap, who weighed not much over 135 pounds, and certainly didn’t look the part of a pitcher.

I also got Arthur Irwin — the famous Arthur Irwin — then but a boy playing on the lots around Boston, to come down and go in at short for me [author’s note: Irwin actually played third base). When I told the fans what I had done they gave me the laugh. “What, come out and see those kids play the famous White Stockings?” was their chanted response to my invitation for their money. “Not on your life.”

Those who refused to come out missed one of the prettiest games that was ever played on any diamond. J. Lee Richmond shut out Anson and his heavy hitters without a hit. Anson asked me if had signed Richmond, and I — for once in my life — told a lie. But I “coppered” my fabrication in what I think was a clever fashion. The dressing room for the players was under the grandstand, and it wasn’t much shucks. So I hired a carriage, and when the game was over got young Richmond by the arm and whispered in his ear:

“Now Mr. Richmond — I used the Mr. because I wished to be diplomatic — there isn’t much of a place for you to dress down here, so I’ve taken the liberty of putting your street clothes in a hack. If you would like I’ll drive you down to a hotel, where I have reserved a room and a bath for you. You can dress there.”

He fell into the trap and I hustled him off to the tavern. There I had no trouble signing him to a contract which called for $100 a month. He was the goods too.

Irwin recalled that Chicago wanted to sign Richmond as well:

Old man Anson was as much struck with Richmond’s playing as President Pratt (of Worcester), and when the young pitcher reached Union Station he found Captain Anson there in uniform. Anson had hustled from the grounds, without stopping to change his uniform, in the hopes of getting Richmond to sign with Chicago before Worcester could have a chance to sign him. Anson’s ruse did not work, however, and Richmond remained with Worcester.

BACK TO COLLEGE

Richmond’s second major win of this fantastic nine-day period was the College Championship contest played at Providence on June 9, 1879. Brown beat Yale 3-2 that day with Richmond hurling as he always did for the Bruins. This was the second meeting of the season between these rivals, Yale having won the first contest 2-0 on Richmond’s throwing error. This, then, was a “must win” game for the Brunonians.

Brown lost the toss and was sent to bat first, leaving Yale with the advantage of batting last on Brown’s home field. Both teams scored a run in the first inning. Brown scored one more in the sixth and what proved to be the deciding run in the seventh. Richmond himself doubled and scored on two consecutive errors. He then held on for the win. Yale scored again in the eighth on a wild pitch but the tying run was cut down at the plate by second baseman Ladd on a ground ball with only one out.

Richmond “took to the points” to pitch the bottom of the ninth inning leading 3-2 with the College Championship hanging on his ability to retire the side. Yale’s leadoff hitter, first sacker Hopkins, singled and moved to second as Richmond threw out Camp. Clark, the Yale center fielder, flied out to White at first. However, Smith was safe on Waterman’s throwing error and Hopkins moved to third. Smith then stole second and the game, which had looked to be in hand before Waterman’s error, was now very much in doubt. Runners at second and third, two out, bottom of the ninth, one-run game — a classic finish for a championship contest and season. To add further to the drama, Richmond got wild. He ran the count to eight balls and one strike (nine balls then constituting a walk) to Ripley. Reaching back for something extra, he got two more strikes to strike out Ripley and end it — a storybook finish that is recalled at Brown University to this day. Richmond himself is remembered as the first of Brown’s athletes to be inducted into her Hall of Fame.

The game remained vivid in Richmond’s memory as he wrote about it in Memories of Brown years later.

This final game with Yale that gave possession of the championship was the most exciting game I ever saw. When Yale went to bat in the ninth inning, the score stood 3–2 against them. By the time two men were out they had the bases full. [author’s note: actually there were runners at second and third]. The game literally turned on one ball pitched, for the next batter waited till he had two strikes and eight balls. The grandstand was as still as death. Numbers of fellows had gone behind the grandstand unable to watch the game. When the last ball was struck at and caught by the catcher — well — I can’t tell you my feelings. I remember having Professor Lincoln shake my hand, and wondering if the other fellows found it as uncomfortable to be hoisted up on shoulders as I did.

FAME

Just two days later, Richmond pitched his third gem in this fantastic nine-day stretch. On June 11, 1879 he faced the Nationals of Washington, D.C. at the Driving Park, Worcester. The Nationals were leading the National Baseball Association at the time. It was Richmond’s first professional championship contest (one that counted in league standings). He bested the league frontrunners 4-1 with a neat two-hitter. Richmond had pitched only two games for Worcester, but he had arrived. His presence would provide the spark that would see Worcester roll through the remainder of the season.

The local press was much impressed. From the Worcester Gazette:

The ball game at the Driving Park, yesterday afternoon, was the neatest game of the day, and the spectators, nearly 1000 in number, cheered themselves hoarse over the numerous fine features of the contest…. Richmond’s wonderful work against the Chicagos, last week, had raised high hopes, and his pitching yesterday was all that could have been expected, only two safe hits being made off his puzzling delivery.

And now, as pitcher for the Worcester club his every effort would be noted by the national press. The game account as it appeared in the New York Clipper:

Richmond’s wonderful pitching enabled the Worcesters to defeat the Nationals at Worcester on June 11 in the presence of over 1200 people. The Nationals could not get the hang of Richmond’s left-handed delivery and made but two single basers off him in the entire nine innings. The Worcesters batted very well, Bennett taking a decided lead in that respect. The game was one of the most exciting ever played at Worcester, and the home nine’s victory was a most credible one.

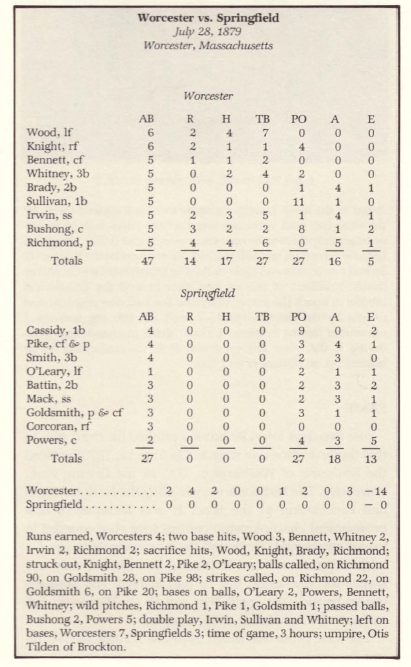

(Click image to enlarge)

So ended Richmond’s “fantastic nine days.” He had won the College Championship with his Brown University team, pitched a no-hitter against the National League leader, and beaten the National Association leader with a two-hitter. He was on his way to a remarkable season that would be marked by fine composite totals and the instant reversal of form by the Worcester club. He was a control pitcher, giving up few walks and striking out more batters than did most pitchers of his time. His defenses recorded unusually high numbers of ground outs. He also helped his cause with the bat, and he took his turn in the heart of the order. On July 28, he no-hit Springfield while knocking out four hits himself-including two doubles-and scoring four runs.

In championship contests through the rest of the 1879 season, Richmond was 18-10 with a league leading earned run average of 1.06. He batted .368 and had a slugging average of .569, leading his team in both categories.

However, there was still much baseball to play. Worcester was scheduled for a slate of exhibition games that would last until mid-October. Featured were contests with the strongest teams of the National League.

Richmond melded participation in these games with attending classes during Brown’s fall term. He played for Worcester in especially prestigious games, the schedule and the game site being the determining factors in whether he would appear. This regimen of pursuing his education and furthering his ballplaying career would continue through 1883, when he would receive his medical degree and play his last full season for the Providence Grays.

The highlights of this postseason exhibition schedule were those contests with Providence, Boston, and Chicago of the National League. Providence would take the pennant by five games over Boston. Chicago, after a fast start, would finish fourth, one-half game behind third-place Buffalo.

Worcester knocked off Boston 4-3 at Worcester on September 11 to set the stage for a very successful exhibition series. The next league team into Worcester was Chicago, on September 18, for a rematch of Richmond’s first professional encounter in June. The White Stockings did not fare much better this trip. Richmond shut them out on four singles.

Mingled among these games with the teams of the “Big League” were almost daily games with other teams, many from the National Baseball Association. Albany, their league’s champion, came to Worcester on September 25. The occasion was the first of a five-game series arranged for the championship of their respective cities. Richmond sent them packing 10-3, recording the then unheard of total of 15 strikeouts.

BIG LEAGUER

Richmond capped off a season of firsts and debuts by playing in his first major-league game on September 27.

Manager Harry Wright of Boston secured Richmond to hurl against Providence in his team’s final league game. The regular Boston pitcher was ill and the change pitcher was also unavailable for this wrap-up game with Providence, which had already clinched the flag. Pitching for Providence was John Montgomery Ward, who had recorded a league high 47 wins in leading the Grays to the pennant.

After a shaky first inning by Richmond and his defense, he pitched a solid 12-6 win, allowing but a single base hit over the last eight innings. He recorded a league record five consecutive strikeouts in his debut in the senior circuit. The New York Clipper felt that the Bostons were a better team with Richmond on the mound:

The Bostons, strengthened by Richmond, the famous left-handed pitcher of the Worcesters, defeated the Providence nine on Sept. 27 at Boston, Mass. The contest was a remarkable one, the visitors being badly beaten, although they started off with a lead of 5 to 0. Singles by Wright and Start and Gross’ three baser earned two runs for Providence, and they made three more runs on errors in the first inning. Richmond then settled down to his work, and the visitors in the next eight innings made but one base hit on him, and that a lucky one to short right field, and scored but one more run, the result of errors by Burdock and Snyder. Eleven of the visitors struck out, five in succession, and we are safe in saying that the chief credit of the victory belongs to Richmond.

Richmond and Worcester went on to split four more games with Boston and Providence. The final game was something of a homecoming for Richmond as Worcester visited Providence, the home of Brown University. J. Lee prevailed again, 3–2, on October 7 in what was both a home and road game for him. This win made him 7–2 against National League clubs for the season, a prodigious record.

Richmond was a busy man. Keeping up with both his studies and his Worcesters was too much for him on one occasion. He mistakenly took the train from Providence to New Haven rather than Worcester for a game with Providence. Failure to meet his team cost him yet another crack at the Grays.

Richmond then rejoined the Brown U. nine for their fall season. Their first scheduled game was with his own Worcester club. Rain interfered, however, and the game was not played. This must have been a great disappointment to Richmond and to the many fans who came to witness another interesting matchup. Brown played four more games, ending their season on October 22. Richmond ended his season as he began it, playing as an amateur. And what a lot of baseball he had played in between!

Richmond’s 1879 exploits paid rich dividends for both him and the Worcester team the next season. Because of Worcester’s resurgence under his leadership the team was admitted to the National League for the 1880 season. The league fathers were so much in favor of admitting the Worcesters that qualifying rules concerning the population of candidate cities were “modified” to allow the Brown Stockings entry. As what may have been sports’ first “franchise player,” J. Lee Richmond was paid a then-record $2,000 salary for his services for the 1880 season. In my view, the admittance of this team from a tiny New England town to the National League was Richmond’s greatest baseball achievement.

PERFECT GAME

The 1880 season was the scene of what others consider as Richmond’s greatest accomplishment on the field, his perfect game against Cleveland at Worcester on June 12, 1880. The perfect game is the milestone event of Richmond’s baseball career, the game that sets him apart from all other pitchers. He was the first of only 10, from the purist’s point of view (discounting the efforts of Ernie Shore and Harvey Haddix), to pitch a perfect game in the entire 110-year history of major-league baseball.

The story of the perfect game is an amazing one. Taken in context with other events that surrounded it, the feat becomes even more formidable. On the Thursday before this Saturday contest, Richmond had shut out the Cleveland team 5-0, also at Worcester. He was in the midst of a streak of at least 42 consecutive innings during which he would not allow an earned run. In addition, the perfect game would be his third shutout within nine days. He returned to Brown for graduation festivities and parties, passing up Worcester’s Friday exhibition game with the Yale nine.

Graduation events included a class baseball game played at 4:50 on Saturday morning. Richmond had been up all night following the class supper at Music Hall. He took part in the ballgame and went to bed at 6:30 A.M. He rose in time to catch the 11:30 A.M. train to Worcester to pitch the afternoon contest against Cleveland. The train on which he rode was delayed and he was forced to go to the field without his dinner. One would not think that proper preparation for a ballgame would include foregoing sleep and food and playing another game earlier in the day.

This train ride has become almost legendary. As the story goes, Frank Bancroft had hired a special train to stand by and rush Richmond to Worcester upon completion of Brown’s graduation ceremonies. The story continues with Richmond proceeding to pitch his perfect game. Great story, but not true. Richmond’s graduation day was four days later, on June 16. On that day Bancroft did, in fact, have a special train waiting. Richmond took this train to Worcester and was beaten by Chicago 7-6 in 1- innings.

The Worcester team of 1880 was very young, the players averaging 23 years of age. The team included several rookies, playing the team’s initial season in the National League. They were enjoying some success, with a 14-9 record early in the season. This series with Cleveland may have offered an extra incentive for Richmond: Cleveland was essentially his hometown team and this was the first time he had ever faced them.

Richmond and big Jim McCormick locked up in a super duel. Richmond himself got the first hit of the game in the fourth, but was erased on a double play. Worcester would get but two more hits the entire day, both by shortstop Art Irwin. The only run of the day scored in the fifth on a double error by Cleveland second sacker Fred “Sure-Shot” Dunlap.

Like so many games that became classic, the game featured a game-saving play. In this case the “saver” may have been the first of its kind. In the fifth inning Cleveland’s Bill Phillips hit a ball through the right side for an apparent base hit. Lon Knight, captain, right fielder, and old man of the team at twenty-six, charged, scooped up the ball, and fired to first. Umpire Foghorn Bradley called the runner out, the no-hitter being preserved. This seems to have been a turning point in the game. Richmond had not struck out a batter. He took complete command, striking out five the rest of the way. His domination was so complete that only three balls were hit out of the infield all day.

An effort was made by Mother Nature to disturb Richmond’s concentration and perhaps halt the string of batters being set down in order. A cloudburst halted the game in the eighth inning for seven minutes. Undaunted, Richmond returned to the box and, using a heap of sawdust to dry the ball, completed the game.

Richmond always kept his achievement in perspective. He once remarked in a newspaper interview that catcher Charlie “Bennett and the boys behind me gave me perfect support.” On another occasion he said, “I couldn’t have pitched it if the fielders had not been so expert in handling the ball.” Richmond knew that an errorless game played by barehanded fielders was a rare achievement in itself.

Just five days later John Ward of the Grays turned in a second perfect effort against Buffalo in Providence. Two perfect games within a five-day period defies all odds. Ward had equaled Richmond’s standard of perfection, a level of play that was not even thought of as being attainable only a week before. The third perfect game did not occur until May 5, 1904, when the legendary Cy Young threw one for Boston (AL). Young’s effort kept the perfect game as an exclusive New England institution. The third perfect game in the National League did not occur for 84 years, when Jim Bunning turned the trick in 1964.

During his remarkable 1879 season, J. Lee Richmond established himself as one of the game’s fine all-round players and foremost pitchers. He did this at a time when baseball was undergoing rapid evolutionary change. He was a major contributor to changes in pitching strategies and philosophies. He was not the first breaking-ball pitcher. Nor was he the first left-hander (“heartside heaver”) to hurl in the National League. He was, however, the first to combine these two then unusual attributes. The results were devastating, especially on a hitter’s first encounter with his unique delivery and pitch. Richmond employed a change of pace and a sharply breaking curve, which broke down rather than out as did the curves of other pitchers. Slight of stature at 140 pounds, he did not overpower hitters. He studied hitters and kept a book on them. His allies were cunning, deception, and strategy. His remarkable 1879 season set off a search for left-handed pitching talent that continues to this day.