Entering the National League: The Phillies’ Bumpy Journey

This article was written by Robert D. Warrington

This article was published in Fall 2022 Baseball Research Journal

NOTE: This is the final installment of a three-part series addressing the founding of the Philadelphia National League Baseball Club.1 Click here to read Part One (1881 Eastern Championship Association) and click here to read Part Two (1882 League Alliance).

Traditional histories of the Philadelphia Phillies portray the club’s entry into the National League as a straightforward and smooth process. It was anything but. Numerous challenges had to be overcome in establishing the franchise and assembling a team for the 1883 regular season. The fledging club was also overshadowed by the rival Athletics, who already held major league status and represented “the first name in Philadelphia baseball.” Whether the Phillies could compete effectively against other NL teams and secure a prominent place in Philadelphia’s baseball landscape was uncertain. Hope attended the Phillies’ ascendance to the National League, but so did doubt, and success was not guaranteed.2

PHILADELPHIA IN THE NATIONAL LEAGUE—AN INAUSPICIOUS START

Philadelphia’s first membership in the National League was a failure.3 The Athletics represented the city during the League’s inaugural 1876 season, but were banished when—out of pennant contention—the club refused to make a final western road trip believing it would lose money by doing so.4 The A’s brief tenure exemplified the organizational tumult the NL experienced in the early years of its existence. The Hartford Dark Blues, Louisville Grays, St. Louis Brown Stockings, and other teams had entered and departed the League’s ranks between 1876 and the Phillies’ arrival in 1883.5

Despite their short stay in the NL, the Athletics remained the lead name in Philadelphia baseball, as they had since the 1860s.6 The 1883 version of the club had a one-year head start over the Phillies in the major leagues. The A’s had become a member of the American Association—a new organization established to challenge the NL’s monopoly on major league status— in 1882.7 The upstart Phillies had spent the year in the League Alliance—the group of minor-league teams affiliated with the NL.8 The Athletics dominated the allegiance of Philadelphia fans, and it remained to be seen if those fans would find room in their hearts to embrace a second major league team.

THE STARS ALIGN FOR PHILADELPHIA’S RETURN TO THE NL

Though the Athletics enjoyed preeminent baseball status in the city, the formation of the Association served as the genesis for the Phillies gaining major league membership. By placing teams in the nation’s two biggest cities—Philadelphia in 1882 and New York the following year—the AA created an imperative for the National League to do likewise. Owners were not about to cede those cities to the Association in their fight to remain the sole major league.9

From a marketing perspective, Philadelphia had a lot going for it as the future home of an NL team. By 1880, the city’s population had grown to 847,170—the second-largest city by population in the United States—trailing only New York (1,206,299).10 Industrial giants dominated Philadelphia’s economy—the Baldwin Locomotive Works, Pennsylvania Railroad, and Cramp shipyards. Together with myriad smaller enterprises they provided steady employment for thousands of workers, many of whom were, or were about to become, devoted baseball fans.11 The game had proven to be widely popular in the city by the time the Phillies joined the National League.12

The position of NL owners who favored allowing Philadelphia and New York to reenter the League was strengthened when president William Hulbert died on April 10, 1882. His refusal to permit those cities to return after teams representing them were expelled for failure to complete their 1876 schedules was the last institutional obstacle to welcoming them back into the fold.13

The advantageousness of the moment for the Phillies to join the NL was further enhanced by the League’s desire to jettison its two weakest clubs—the Worcester Brown Stockings and Troy Trojans—from the ranks.14 At a September 22, 1882, NL owners’ meeting, it was announced that both Worcester and Troy had resigned from the league effective the end of the season, and that clubs from Philadelphia (Phillies) and New York (Metropolitans) had filed applications for membership to replace them.15

The Phillies’ time in the NL-affiliated League Alliance in 1882 had served as a crucial prelude.16 Membership in the alliance afforded the Phillies the opportunity to develop their organizational structure, build a ballpark, assemble a pool of talented players, develop a fan base, and compete against a variety of opposing teams. All of this was done under the watchful gaze of NL owners eyeing the club as the League’s future Philadelphia representative.17 Thus the Phillies began the 1883 season possessing many features of a more established major league franchise.

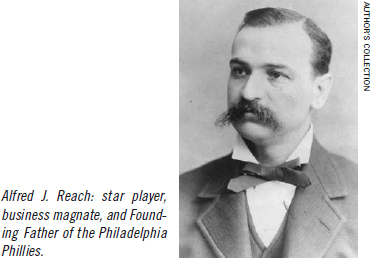

REACH IS THE PHILLIES’ FACE, BUT NOT ITS PATRON

The Phillies were also fortunate to have a former star player and by then a highly successful businessman as their president—Alfred J. Reach—who had led the club when it was in the League Alliance.18 His baseball career had begun in the 1860s as a member of the Brooklyn Eckfords. A talented player, Reach became the first openly professional baseball player in 1865 when he accepted $25 a week to play for the Athletics. Upon leaving Brooklyn for Philadelphia, Reach also became to first player paid a salary to change cities to play baseball.19

As his career started to wind down, Reach turned his talents to entrepreneurial pursuits. Beginning with a cigar store, he expanded into sports equipment manufacturing, opening his first sporting goods store in 1874.20 Reach’s businesses prospered, and achieving considerable wealth provided an opportunity to pursue his continuing passion for baseball—if not on the field, then in the front office.21

Although portrayed by some authors as champing at the bit to join the National League, Reach was far too prudent a businessman to allow unbridled eagerness to dictate his decisions.22 He took actions to strengthen the Phillies’ management structure and limit his own financial investment in the club should the venture fail.

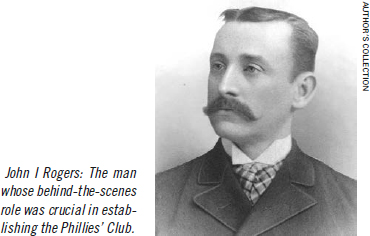

Reach procured a partner to work with him in running the new ballclub—John I. Rogers—a well established lawyer with political connections in the city.23 While acting primarily in a behind-the-scenes role, Rogers handled all the club’s legal issues, conducted salary negotiations with players, and used his influence at City Hall to gain preferential treatment for the Phillies in municipal assessments, services, and fees.24

Despite having the welcome mat laid out for him, Reach’s misgivings about the Phillies’ viability as a major league club caused him to hesitate upon receiving the offer to join the League, arousing the ire of NL owners. The resulting friction was noted in an article in the New York Clipper on October 7, 1882:

The reason that the Philadelphia Club entered the League was because Al Reach was told that if he did not, a League club would be placed in Philadelphia which would throw out the League Alliance club.25

Reach’s negotiating position was sufficiently strong, however, that threats alone would not cause him to ignore his doubts. The League had helped subsidize the Phillies financially during the 1882 League Alliance season while positioning the club for NL membership the following year. The inducements included having League teams travel to Philadelphia to play 65 games, their presence guaranteeing larger crowds for Phillies’ home games. The Phillies, meanwhile, did not play away games in any NL cities, helping to minimize the club’s expenses for players’ travel, room and board.26 With NL owners promoting fans’ attendance at Phillies’ games and curtailing the club’s operating costs, the Phillies avoided incurring substantial debt in their League Alliance season.27

By the time the NL tendered its membership offer, moreover, Reach had become the face of the Phillies.28 He solidified that leadership position by being the club’s spokesperson during the 1882 season, and his standing in Philadelphia as a former star player and wealthy businessman enhanced the club’s major league credibility and standing with the public. Rogers, mean-while, occupied an equally important position in establishing the organization’s administrative, legal, and financial relationships with the League and the city. Without Reach at the helm, an infrastructure already in place to operate the team, and a political insider (Rogers) to ensure the city’s cooperation in assisting the club’s operations, the NL owners’ threat of a last-minute, hastily assembled, unknown and untried team being installed as the Philadelphia League representative was toothless.

NL owners also confronted a genuine public relations disaster if Reach turned his back on the National League. The Metropolitans—simultaneously groomed to enter the League as the New York member—decided in October to join the American Association instead.29 How humiliating would it be to the League if both clubs, representing the two largest cities in America, declined to join?

Leveraging their bargaining advantage, Reach and Rogers decided to limit their monetary commitment in the Phillies. Insufficient wealth was not the issue; playing it safe was. If the club foundered, their losses would be minimal. Reach and Rogers insisted on running the club, but sought another individual to become majority shareholder. They needed someone who would risk the largest financial investment in the franchise without being in charge of it. NL owners— likely in consultation with Reach and Rogers—used the period between the owners’ meeting on September 22 and the end of October to search for such a person.

IS FARRELLY A BACKER OR A FRONT?

On November 1, 1882, the Phillies incorporated as the Philadelphia Ball Club, Limited.30 The amount of capital in founding the franchise, according to the partnership agreement, was $15,000, divided into 150 shares at the value of $100 per share. The partners and their share purchases were as follows:

- Stephen J. Farrelly (100 shares: $10,000)

- Alfred J. Reach (20 shares: $2,000)

- Thomas J. Pratt (20 shares: $2,000)

- John I. Rogers (10 shares: $1,000)

The four men were identified as members of the Phillies’ Board of Directors. As a reflection of their determination to be in charge despite being minority stockholders, Reach was elected Chairman of the Board and Rogers its Secretary and Treasurer. Farrelly and Pratt held no management titles.31 While Reach’s and Rogers’ associations with the Phillies are well-known, Farrelly’s and Pratt’s are not.

Thomas J. Pratt

Thomas Pratt was a noteworthy pitcher during the earliest days of baseball in Philadelphia.32 In 1860, he joined the Winona Club as a pitcher/outfielder. In 1861, Pratt became a member of the Athletics and stayed through the 1863 season, after which he switched to the Atlantic club of Brooklyn. Pratt reached his peak as a pitcher with the Atlantics in 1864–65, going undefeated those years (19–0, 13–0). Between 1866 and 1870, he played for various teams including the Athletics and Quaker City teams in Philadelphia. In 1871, Pratt was a member of the Athletics that also counted Al Reach among its players.33

Whether that is when the men first met, or if they had become acquainted earlier, is not known. What is certain is that when Pratt purchased 20 shares of Phillies’ stock—equaling the amount bought by Reach—the men knew each other and had extensive backgrounds in baseball.

For Pratt, remaining uninvolved in operating the team was not enough, and he sought a more active role in directing a ballclub. In 1883, Henry Lucas decided to finance the Union Association, an organization intended to operate as a major league in 1884.34 Newspapers reported Pratt would become owner of the Keystones—Philadelphia’s entry in the Association—and he attended its inaugural meeting held in Pittsburgh.35

NL rules expressly forbade any of its owners from having a financial interest in a club belonging to another organization that claimed to be a major league but was not recognized as such by the National League. This applied to the Union Association, whose formation was opposed by the NL and AA, neither of which wanted a third major league. A newspaper article reported the Phillies would be called to account by the League if Pratt continued holding stock in the club while also being an investor in the Keystones.36

How this was resolved is unclear, but Pratt almost certainly was compelled to relinquish his stock in the Phillies at some point in 1883 or no later than 1884 when the Union Association began operating. There is no evidence Pratt’s association with the Phillies continued after becoming one of the initial stockholders, nor is there any evidence suggesting his role on the club ever extended beyond owning a minority share of the stock.

Pratt’s Keystones, meanwhile, were a failure at the turnstiles and on the field. After falling to eighth place (21–46), 50 games behind the league-leading St Louis Maroons, the club announced on August 7 it would leave the Association. Reports indicated the Keystones had lost between $10,000 and $12,000 since the season’s beginning.37 The Union Association folded after the 1884 season.38

Stephen J. Farrelly

Stephen Farrelly is the most mysterious character in the Phillies’ original ownership group. In late 1882 when he became chief stockholder of the club, Farrelly was the head of the Central News Company (CNC) in Philadelphia.39 The company’s business was “purchasing, importing, vending and distributing books, newspapers and other printed matter, fruit, candy and similar refreshments, cigars, cigarettes, tobaccos, soft drinks, miscellaneous novelties and merchandise of a like kind in the city.” The primary sites where CNC plied its trade were newsstands located in commercial and business sections of Philadelphia.40

As business and civic leaders, Reach and Farrelly undoubtedly knew each other, an acquaintance made all the more familiar by the proximity of CNC’s headquarters at 252 South Sixth Street with Reach’s sporting goods store located at 23 South Eighth Street.41 Farrelly’s company may even have supplied tobacco products to Reach’s cigar store located at 404½ Chestnut Street in Philadelphia.42

But Farrelly had no known links to the Phillies or the game of baseball, and nothing about his background or profession made him a likely candidate to invest $10,000 in the club—a figure far exceeding the sums of other investors. At this point John R. Walsh enters the story.

Empire builder, financial magnate, and millionaire, John R. Walsh of Chicago owned some eighteen different companies, including three Chicago-based banks and several railroads in Indiana. He also owned the Western News Company (WNC), which brought him into contact with Farrelly and CNC. WNC and CNC each held a regional monopoly on newspaper and magazine circulation in the territories they controlled, making cooperation between the two businesses essential in setting and enforcing distribution charges imposed on content providers.43

In addition to these holdings, Walsh was a stockholder in the NL’s Chicago club. Period newspapers and magazines identify him as the “owner” of the club, but he was only a stockholder.44 Although club ownership details for that time are sparse, the chief investor almost certainly was Albert G. Spalding, who became president of the franchise in 1882 after William Hulbert died.45 Walsh and Spalding were ardent proponents of the National League, and their efforts to ensure its success extended to using their own money to support clubs that were just starting out or experiencing financial difficulties.46

It was John Walsh who reached into his pocket to bridge the Phillies’ investor funding shortfall, thereby ensuring the franchise would be financially solvent when it joined the League. Stephen Farrelly was the front, investing what was purportedly his money in the club, but which actually came from Walsh’s wallet. This fact was unknown when the Phillies were incorporated in November 1882, and the truth did not surface until 20 years later when Reach and Rogers sold the club. A Philadelphia Inquirer article from 1902 revealed it:

The Philadelphia Ball Club, Limited was organized in 1882, with a capital of $15,000. Of this capital, $10,000 was subscribed in the name of Stephen Farrelly, who was then agent of the Central News Company in this city. As a matter of fact, however, the money was understood to have been really subscribed by Mr. John R. Walsh, of Chicago, then, as he is now, one of the principal stockholders of the Chicago National League Baseball Club.47

But why use Farrelly to mask the true identity of the majority stockholder? The reason was to avoid charges of “alien ownership” that could undermine fan confidence in two ways. Would owners residing in other cities be more focused on making profits than winning championships for local pride, or worse, favor their other team(s)?48 The inherent conflict of interest in “syndicate baseball” found in the National League in the late nineteenth century created doubts about the League’s commitment to fair play. “Syndicate baseball” refers to the same individual or group of individuals simultaneously owning or being principal investors in more than one club.49

The same person owning more than one club was already roiling NL–AA relations in 1883. Both leagues wanted a club in New York—the largest market—and they had each offered membership to John B. Day’s Metropolitans. Day declined the NL’s invitation, enrolled the Metropolitans in the American Association, and then, in a surprising move, announced the formation of a new club, the New Yorks (later Giants), that would join the NL.

The Association objected, believing Day would favor the New Yorks and treat the Metropolitans as New York’s “other” team. These concerns were well-founded. Events proved “…Day’s intention to make a champion of the (New Yorks), and to that end, the Metropolitans would be sacrificed.”50 In their last two years in the Association, “the Metropolitans were simply a doormat performing in out-of-the-way Staten Island, a dropout waiting to happen.”51

That Farrelly’s (i.e., Walsh’s) investment in the Phillies was no more than a temporary expedient to facilitate the club’s entrance into the National League became apparent over time.52 The team enjoyed financial success and became a profit-making enterprise after joining the League.53 Farrelly’s stock was eventually bought up by the other owners, with John Rogers leading the way. He became the majority stockholder in 1895 by owning 78 of the club’s 150 shares.54

SETTLING THE FEUD

With the Phillies’ financial affairs in order, Reach and team manager Bob Ferguson shifted their focus to preparing for the 1883 season. First, however, there was a feud to be resolved. How it was settled would have a direct impact on the composition of the Phillies’ roster and the club’s exhibition schedule.

The Phillies’ entrance into the National League occurred against the backdrop of an ongoing dispute between the League and the American Association over the latter’s claim to be a major league. NL owners refused to acknowledge the Association as an equal, and the resulting friction between the two organizations was further exacerbated by “contract jumping” by players who signed with a club and then hopped to a different team for more money.55

Al Reach longed to play the intracity rival Athletics. He knew the games would stimulate fan interest beyond other potential matchups, and serve as a forum to demonstrate the Phillies’ legitimacy as a major league franchise. Reach knew because in 1882 his then League Alliance club’s two contests against the Athletics drew far more fans to the Phillies’ ballpark than any other game his team played that year.56 The intracity gravy train had only come to an abrupt halt because of a dispute between the League and Association. John “Dasher” Troy had jumped his contract with the Athletics and switched to play for the NL’s Detroit Wolverines. The Association demanded Troy’s return, and after Detroit demurred, declared its clubs would no longer play games against League or League Alliance teams. The decision ended Phillies-Athletics square offs for the 1882 season.57

Reach’s financial incentives went beyond his take of the gate receipts. The Association was a lucrative market for products sold by his sporting goods company.58 Now an NL owner, the last thing he wanted was to have his business dealings upended by bad blood between the two organizations. Fortunately for him, the League and Association recognized the deleterious effects the feud was having on their operations and profits. Leaders from both organizations met on February 17, 1883, and reached a “National Agreement.”59 Not all issues were resolved, but enough of the major disagreements were settled—the reserve rule was raised to 11 men per team, and the two organizations agreed to honor each other’s contracts and blacklists—that Association president Denny McKnight lifted his ban on interleague exhibition games.60

Reach’s financial rewards included the Association’s executive committee selecting his company’s baseball as the one to be used in games during the 1883 season:

The applicants included Mahn, Shibe, Wright & Ditson and Al Reach, and each was heard before the committee. As Al Reach made the most favorable bid for the privilege his bid was accepted, and the Reach American Association ball will hereafter be the only legal ball to be used in all club matches by the American and American-alliance clubs during 1883.61

The Interstate Association—affiliated with the AA as a League Alliance—selected Reach’s ball for all of its games in 1883 as well.62 Reach also was given the contract to print The American Association Baseball Guide for 1883 which a sportswriter called “one of the most complete and valuable annals published in connection with the national game.”63

While the “National Agreement” allowed Reach to include the Athletics on the Phillies’ exhibition schedule, new frictions soon emerged that cast the games in doubt. In the meantime, building a team roster took first priority.64

THE PHILLIES’ ROSTER TAKES SHAPE

Al Reach had no illusions about the difficulties his club would face in competing against NL clubs in 1883. During the 1882 season, the Phillies had played 65 games against League teams, winning 16, losing 44 and tying five.65 One of Reach’s primary goals became, in the words of one sportswriter, “to secure several good young amateurs to strengthen any weak points in the team that will represent Philadelphia in the League in 1883.”66

To discover such qualified players, Reach turned to two veteran ballplayers. He asked future Hall of Famer Cap Anson “to keep a look out for me, and let me know if he came across any desirable players.”67 Reach also relied on Bob Ferguson to find diamonds in the rough. A longtime player-manager in the National League—most recently piloting the Troy team—Ferguson was quickly hired as the Phillies’ new manager after the Trojans had departed the League.68 Ferguson’s task was to use his contacts in baseball and visit amateur clubs to find major league-worthy talent.

Sportswriters forecasting the composition of the Phillies’ 1883 team judged it would consist of holdovers from the 1882 roster augmented by new arrivals. A reporter with the Philadelphia Inquirer offered this prediction of the Phillies’ roster:

(John) Manning, (Fred) Lewis, (William) McClellan, (Jack) Corcoran, (Roger) Connor, (William) Ewing, (Peter) Gillespie, (Timothy) Keefe, (Jack) Neagle, and (Hardie) Henderson will be members of the Philadelphia nine next season.69

Manning, Lewis, McClellan, Corcoran, Neagle, and Henderson had played for the Phillies in 1882, while Connor, Ewing, Gillespie and Keefe had been with Troy that year.70 Why the sportswriter supposed Troy players would come en masse to Philadelphia is puzzling, especially given the fact none of them did.71 None of the players from Worcester, the other outgoing franchise, joined the Phillies either.72 Projections of the Phillies’ roster continued to appear in newspapers as the season drew closer. Although the names of players varied somewhat, the lists always included a core of veterans from the 1882 campaign; most prominently, Neagle, Henderson, McClellan, and Manning.73

HARDIE HENDERSON’S LEGAL PROBLEMS

Controversy, however, complicated building the roster. It started with Hardie Henderson, the pitcher who had provided yeoman’s service to the Phillies in 1882, starting 52 games and compiling a record of 28 wins, 21 losses, and three ties.74 His troubles became public knowledge on December 7, 1882, when the Philadelphia Inquirer ran an article with the headline, “A Base Ball Player Implicated in the Death of a Young Girl.”

According to the article, Sarah McLaughlin had become ill—a condition initially diagnosed as “cramps” by the doctor who examined her. McLaughlin’s condition worsened over the next several days, and she confided to her mother shortly before dying “that the cause of her trouble was some ‘stuff’ which she had taken from a bottle given her by one James Hardy Henderson.”75

The Coroner’s Office held an inquest and autopsy results concluded that “peritonitis, the result of malpractice” had caused McLaughlin’s death. The Coroner’s Jury returned a verdict that “the deceased came to her death from malpractice, the result of the drug administered by herself and furnished by James Hardy Henderson.” A warrant was issued for Henderson’s arrest, and he was taken into custody when found at a saloon in the city. Placed in jail “to await the action of the grand jury,” Henderson is described in the article as a “ballplayer [who] had gained considerable note as a pitcher last season for the Philadelphia Base Ball Club.”76

Because no subsequent reporting on this story could be found in the Inquirer or other local newspapers, it’s uncertain what really happened. There is no evidence Henderson completed high school, attended college, or was a licensed physician. The nature of his relationship with McLaughlin is unknown. He was 20 at the time. McLaughlin’s age is not listed, but she is referred to as a “young girl” in the article.77 During the late nineteenth century, “young girl” could mean any unmarried female up to the age of 18.78

While numerous questions surround the case, a possible explanation is that Henderson had gotten McLaughlin pregnant and gave her a medicine advertised to end a pregnancy by inducing a miscarriage. Not only were such medicines ineffective, they could cause grievous harm and resulted in the death of women who took them with tragic regularity. McLaughlin’s symptoms are consistent with those experienced by women who took these fraudulent medications during the late nineteenth century.79

If Henderson was unwilling to get married, then McLaughlin may have wished to avoid the social opprobrium—prevalent at the time—of giving birth while unwed, which could also explain her reluctance to identify the cause of the “trouble” to her mother until her condition had become dire. Whether the autopsy revealed McLaughlin was pregnant is not known. If she was, then that information was not included in the newspaper story almost certainly out of deference to her reputation and the family’s privacy. What is known is that Henderson was never tried in court for whatever involvement he may have had in McLaughlin’s death.

Based on his 1882 performance, the Phillies undoubtedly anticipated Henderson would be a key member of the pitching staff in 1883. He was with the club at the beginning of the season, but he pitched in only one game before being released. The fact he gave up 24 runs in that single appearance may have contributed to his abrupt departure from the team.80 Henderson subsequently pitched for Baltimore (AA), Brooklyn (AA), and Pittsburgh (NL) before ending his major league career during the 1888 season.81

TO WHOM DO COLEMAN AND RINGO BELONG?

A second major imbroglio the Phillies faced while compiling a roster involved pitcher John Coleman and catcher Frank Ringo. In November 1882 the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that both men had signed to play with the club the next season.82 But a mid-January article in the New York Clipper stated that Coleman and Ringo had signed to play for the Peoria Reds of the Northwestern League and were subsequently “tempted to break their contracts by Reach and Ferguson.”83

Reach shot back with a letter appearing a week later in the Clipper that asserted:

Coleman and Ringo signed contracts with the Philadelphia Club either in late October or early in November…Neither Coleman nor Ringo or any club have intimated to me they have signed elsewhere, and I received a letter from Coleman as late as this week.84

The next volley came from Charles Overrocker, who was quoted in the Clipper in late January as stating he had signed the two players to the Reds on October 22, 1882, and that Coleman acknowledged signing the contract when it was shown to him the previous week. Overrocker also disclosed that Coleman told him he had written for his release from the Phillies but had been refused. In addition, Overrocker declared, “The Peoria Club intends to hold them.”85

But the ground was shifting under his feet. An article in the Clipper citing an unnamed source stated Overrocker was a member of the Quincy Club, “and had no authority to represent the Peoria Reds in the matter of Ringo and Coleman.” The newspaper also reported the players had notified Phillies’ management they would honor their contracts with the club.86 The controversy was finally laid to rest at the February 17, 1883, conference held by the National League, American Association and Northwestern League to resolve a number of issues that were causing friction among the organizations.87

One of the major agreements reached was that the League, Association and Northwestern League would respect each other’s player contracts. This was particularly important to the latter since the League and Association had purloined players from it in the past by sounding the siren’s call of higher salaries.88

As part of the process of settling outstanding disputes over which organization had legal contracts for which players, the Northwestern League renounced all claims on Ringo and Colemen. The League’s president—Elisa Mather—was quoted as saying, “Let bygones be bygones.”89

Names of other players who signed to play with the Phillies in 1883 appeared periodically in newspaper accounts as the season approached. Some examples follow:

“C.C. Roberts, who played second base for the Rockford Club last season, will be given a trial on first base by the Philadelphias. He is about twenty-two years of age, and is said to be a very promising player.”90

“Alexander McKinnon has signed a contract to play with the Philadelphia Club for 1883. The Boston management feels very much disappointed at his action, as they counted on securing his services.”91

“Charles W. Gaunt, the third-baseman of the Nameless Club, the amateur champions of Brooklyn, has been engaged by Manager Ferguson to fill the same position for the League team of Philadelphia next season.”92

“Weston D. Fisler is to be given a trial at first-base by the Philadelphias. Fisler, who gave up playing in 1878 [sic], was connected with the Athletics for thirteen [sic] successive seasons, and had few equals as a general player, being a magnificent batsman and thrower, while able to field finely in almost any position.”93

Signing with the club did not mean making the regular season roster. Despite the praise bestowed on these players’ baseball skills by sportswriters, neither Roberts, McKinnon, Gaunt, nor Fisler played in any Phillies’ games during the regular season.94

THE EXHIBITION GAMES

The Phillies scheduled a series of exhibition games throughout April to allow Reach and Ferguson to evaluate players’ abilities and separate the wheat from the chaff.95 The games and associated preseason training were held in Philadelphia at Recreation Park. The ballpark was hardly an ideal location for preseason conditioning. Some accounts of exhibition games that appear in newspapers mention threatening weather— rain and cold—that forced games to be called early and limited the number of patrons willing to attend.96

Field conditions also left much to be desired. The poor condition of the grounds reduced the quality of play, increased the chance of injury, and in one case compelled a game to be called after the fifth inning “on account of the bad condition of the ground.”97 The groundskeeper’s job was not made any easier by the fact Reach had allowed the field to be used for football in 1882 once the baseball season was over.98

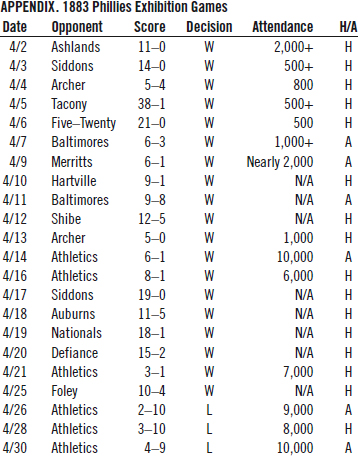

The Phillies played 22 exhibition games during April 1883, but the schedule did not include any games against other NL members. The opponents they did play can be divided into three categories: the Athletics, Association clubs other than the Athletics, and amateur teams. (See Appendix for a list of the Phillies’ exhibition games, including opponent, score, won-loss, attendance, and home-away.) The cost of admission to attend games was twenty-five cents.99

ATHLETICS

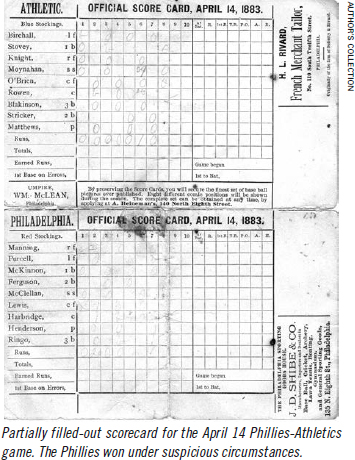

Contests against the Athletics’ club were unquestionably the marquee games of the preseason since they were described as determining the champions of Philadelphia.100 Interest in the games was so intense that Reach had to go on record to confirm the price for a ticket would not be increased to fifty cents to take advantage of the expected larger crowds.101 Six scheduled games were clustered in mid-to-late April, so both teams could spend the first two weeks of the month limbering up against amateur clubs. Each team would host three games—April 14, 21, and 28 at the Athletics’ Jefferson Street Grounds, and April 16, 23, and 30 at the Phillies’ Recreation Park.102

Issues had to be resolved, however, before the games could commence. As noted previously, the NL-AA “peace” agreement in February permitted teams in the two organizations to play exhibition games against each other. The League and Association, however, did not play games by the same rules, and they remained unreconciled. For example, the League required a foul ball to be caught on the fly before a batter could be called out; the Association retained the one-bounce out rule. The League allowed an umpire to call for a new ball at any point in a game; the Association mandated an umpire must wait until the end of a complete inning before introducing a new ball.103

The Phillies and Athletics had to resolve under which set of rules their games would be played. In a decision that presaged interleague play of the late twentieth century, games hosted by the A’s would be played using Association rules and umpire, and games hosted by the Phillies would be played using League rules and umpire.104 The clubs simplified matters somewhat by agreeing Billy McLean would umpire all their games.105 An experienced and respected umpire who lived in Philadelphia, McLean had been the umpire for the first game in NL history on April 22, 1876, between Boston and the Athletics.106

Another issue arose, however, that became a serious point of friction between the two clubs. The NL and AA constitutions gave clubs territorial rights within their home cities. For a League team to play an exhibition game against the Athletics in Philadelphia required the Phillies’ approval. The Phillies’ consent was also needed if clubs in the Northwestern League wished to play the Athletics at the Jefferson Street Grounds.107 The same veto power extended to the Athletics should another Association team or a member of the Interstate Association—the AA’s League Alliance affiliate—seek to play the Phillies at Recreation Park.108

The Athletics hoped to attract League clubs to Philadelphia for exhibition games, recognizing that such opponents would almost assuredly draw big crowds to their ballpark. The Phillies, however, refused to give their consent. The decision may have reflected some envy on the Phillies’ part since no League teams were scheduled to visit Recreation Park during preseason.109

The Athletics retaliated in kind. The Phillies had a two-game, home-and-home series scheduled against the Association’s Baltimores, but the A’s refused to sanction the game in Philadelphia, so both contests had to be played in Baltimore.110 In addition, the Camden Merritts of the Interstate Association planned to visit Recreation Part for two games, but again, the Athletics nixed the plan, forcing the games to be moved to the Merritts’ ballpark. While shifting the game across the Delaware River from Philadelphia to Camden involved minimal inconvenience, the Merritts’ ballpark could hold 2,000 spectators at most, far fewer than the 6,500-capacity Recreation Park.111

Despite the tit-for-tat sniping, neither club allowed it to escalate to the point of jeopardizing their own head-to-head series. The games had been approved by the League and Association, and neither would look kindly on clubs reneging on the agreement out of pique. The games, furthermore, promised a sizable financial return, and officials on both teams were not prepared to cast that aside.

If Phillies’ and Athletics’ owners expected big crowds at their series, they were not disappointed. The six games drew over 40,000 fans to their ballparks, dwarfing the size of crowds attending the teams’ other games. Attendance of 10,000 fans was reported for two of the games at the Jefferson Street Grounds. The grandstand and bleachers were so densely packed, according to one report, that ropes were used to cordon off the outer portion of the outfield so the overflow crowd could stand behind them to watch the games.112 Even unpleasant weather didn’t daunt the spirits of those eager to see the battle for the city championship. The second game held on April 16 at Recreation Park was played in “a cold drizzling rain, making it extremely uncomfortable for both players and spectators.” Yet it still drew 6,000 people.113

The Athletics were expected to dominate the series since, as one sportswriter put it, they were “one of the strongest in the American arena,” while the Phillies were regarded as “the weakest in the League.”114 But those who thought Reach’s team would be a walkover for the A’s were mistaken. The Phillies won the first three contests by scores of 6–1, 8–1, and 3–1.

The first game at the Athletics’ ballpark on April 14 proved especially one-sided—even suspect. The A’s committed 11 errors including dropped fly balls, poor throws, ground balls that fielders failed to stop or fumbled after picking up, and “a high [fly] ball which through bad captaining fell to the ground untouched.” All six Phillies’ runs were unearned. One sportswriter covering the game wrote:

The Athletics not only marred their efforts to win, but greatly helped their adversaries to a confidence which was in itself half a victory… The Athletics were badly captained. They did very little team-work together, and were sadly lacking in skillful play at the bat.115

Accounts of the game contained remarks on the presence of gamblers at the ballpark, with one sportswriter observing, “Large sums of money changed hands on the result.”116 Another commented, “The betting men thought they could win easily, and their money talked….”117

Based on such reporting, an obvious question arises: “Was the game on the level?” A definitive answer is unknowable, but the aforementioned newspaper accounts suggest it was not. In his analysis of the history of gambling in baseball, historian Rob Neyer called the 1865–1920 period a “Stinking Cesspool of Greed.” While acknowledging the title is a “gross simplification,” Neyer argues it is “generally accurate.” In judging whether the Athletics-Phillies game may have been fixed, an assessment in Neyer’s study is particularly relevant:

Prior to 1921 there were so many scandals and near scandals and non-scandals that it’s impossible to list more than a small percentage of them …It’s worth noting that baseball’s scandals weren’t related to players betting on baseball games, but rather to players being paid to lose by gamblers betting on baseball games.118

Exhibition games were particularly ripe for corruption. Compared to regular season games, deliberately losing an exhibition match was relatively painless for a club because it had no bearing on the pennant race. Preseason games were primarily intended to help prepare players for the upcoming season; winning them was a secondary consideration.

If the April 14 game was fixed, then the only real losers in the outcome were the people who bet on the Athletics to win. The players came out ahead if they were paid to lose what they likely regarded as a largely meaningless game. The big winners, though, were those gamblers who in placing their money on the Phillies to win knew they were betting on a sure thing.

Any suspicions about the integrity of play in the first intracity game certainly did not dampen fans’ enthusiasm for the series. Regardless of which team won an individual contest, people continued to flock to watch the contests because of the intensity of the Phillies-Athletics rivalry.

After losing the first three games of the series, the Athletics came storming back to win the last three—the only exhibition games the Phillies lost during preseason.119 The team had won 19 games in a row when they were stopped, 10–2, on April 26. A reporter covering the game noted, “The Athletic nine both out-fielded and out-batted their opponents.” The A’s cruised to victories in the last two games, 10–3 and 9–4, playing truer to form and showing the skills that would lead the team to the Association championship in 1883.

Beyond rousing themselves to play to their full potential, Athletics’ players grasped at an irrational, but apparently persuasive, explanation for their sudden dominance over the Phillies. After the team’s third loss in a row to Reach’s club, they decided a change was necessary, as recorded in an article that appeared in the New York Clipper:

“Joe Quest,” the colored bat-carrier, has been released by the Athletics. The nine thought that “Joe” was a “Jonah,” and since their victories over the Philadelphias, they are certain of it.120

BALTIMORES

The Phillies journeyed to Baltimore on April 7 to play the Association’s Baltimores at their new ballpark called Oriole Park.121 The game marked the Phillies’ first match against a major league club since joining the National League. All previous games had featured amateur teams as opponents. A newspaper account of the game noted it was “the first professional game of the season” for Reach’s team and for Baltimore.122

When the Phillies traveled to play the Baltimores, they could not escape the controversy that seemed to beset them throughout the preseason. The Philadelphia nine won the game, 6–3, before a crowd of more than a thousand. The fans, however, were none-too-pleased by the calls of the umpire. The Phillies had brought Wesley Curry with them to officiate the match, and according to one newspaper report, “His decisions gave great dissatisfaction to the spectators.”123

The teams returned to Baltimore for their second game on April 11. The Phillies again emerged victorious by a 9–8 score. What made the game noteworthy was that it featured the club’s biggest comeback in an exhibition match. Down 8–5 going into the bottom half of the ninth inning, Reach’s team scored four runs to eke out a win.124

AMATEUR CLUBS

The Phillies played most of their exhibition games against amateur clubs—13 of 22—winning them all. All of these contests were held at Recreation Park. With few exceptions, the amateurs were not tough competitors. With scores like 38–1 (Tacony), 21–0 (Five-Twenty), 19–0 (Siddons), and 18–1 (Nationals), it is clear games against such clubs were intended primarily to condition players, practice basic skills and improve teamwork on the field. Still, some games are worthy of note:

In the Phillies’ first exhibition game, John Coleman pitched a no-hitter against the Ashland club, allowing one walk with two other players reaching first base on errors.125

In the second game (vs. the Siddon club), Hardie Henderson repeated Coleman’s feat by throwing a second no-hitter in a row. One batter reached base on a walk, and two others did so through errors. And Fred Lewis hit the Phillies’ first home run, a shot over the right-field wall.126

The game against Archer on April 10 was the Phillies’ first extra-inning match, going ten innings to reach a decision.127

Pitchers on amateur clubs were often victimized by their teammates’ poor fielding. Of the 21 runs scored by the Phillies against the Five-Twenty club, only seven were earned.128

Despite the lack of stout opponents, these games served another useful purpose for the Phillies—the opportunity to assess players on amateur teams who might be added to the roster. For example, when D. Gallagher—pitching for the Archer club—faced the Phillies on April 13, he gave up only one earned run.129 Reach and Ferguson were sufficiently impressed to put Gallagher in the pitcher’s box for a game against Auburn on April 18. He did not pitch poorly, but was wild at times, and catcher Frank Ringo had trouble handling him. None of Auburn’s five runs was earned, but Gallagher was gone from the Phillies’ roster after that sole appearance, never to return.130

The 1883 Phillies’ preseason had enabled club officials to identify the most talented players—individually and collectively—to field the strongest team to compete at the major league level. Numerous players were evaluated, and those found wanting were dropped131

The evaluative process continued into the regular season, causing considerable turnover on the roster. Numerous players were given brief tryouts—sometimes a single game—and then discharged so others could be appraised. The extent of this testing is evident: the Phillies had 29 different players on their roster in 1883, more than any other NL club—in some cases, more than double the number.132

But no amount of preparation and planning could avoid the disastrous season that lay ahead for Reach’s team. Displaying all the weaknesses of a fledgling club, the Phillies combined the lowest batting average (.240) with the highest earned run average (5.34) in the League to finish in last place with a record of 17–81, 46 games behind pennant-winning Boston.133 The team’s winning average of .173 remains the lowest in Phillies’ history134 It was a bleak beginning.

FROM DISMAL ORIGINS EMERGES ENDURING SUCCESS

Despite the turbulence surrounding the Phillies’ entry into the National League, Al Reach could take great pride in the fact he was now president of a major league club. More struggles lay ahead in achieving equal competitive standing with the more established teams, but the Phillies’ ability to endure during their embryonic years heralded their ultimate success. Better times were remarkably close at hand. In 1887—only four years after the atrocity that was the 1883 season—the club finished in second place in the League.135

And what of the goal Al Reach set out in 1882 to have his Phillies emerge from the Athletics’ shadow and exist as a prominent franchise in Philadelphia? He surpassed it. The Association’s Athletics and their successor of the same name in the American League have long since faded into history. The Phillies continue. For the game he loved so much, Reach was a winner for himself and for the City of Philadelphia.

ROBERT D. WARRINGTON is a native Philadelphian who writes about the city’s baseball past.

Notes

1. Part One, “Philadelphia in the 1881 Eastern Championship Association,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2019. Part Two, “Philadelphia in the 1882 League Alliance,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2019.

2. “Phillies” is used as the nickname for the Philadelphia National League Baseball Club in this text. It was not the team’s only nickname in the 1880s. The club was most often referred to as the “Philadelphias” in newspaper accounts of games, achieved by simply adding an ‘s’ to its hometown, as was done in referring to other teams. Additional monikers used to refer to Reach’s club included “Philadelphia Club” and “Philadelphia Nine.” Phillies is used throughout the text to avoid confusion, and because that is the nickname that prevailed as others were dropped over time.

3. For the sake of readability, words spelled differently in the 19th century compared to the 21st century have been modernized. For example, baseball was spelled as two words in the 1880s, but the modern spelling of it as a single word is used in this text. In addition, team names were spelled in singular form in the 19th century. The Philadelphia team in the 1883 American Association was called the Athletic Club of Philadelphia. These and other team names have been pluralized in the text to reflect contemporary usage, and because the clubs themselves began to pluralize them after a few years. The only exception to this rule is when quotations are used in the text. Then, the spelling is kept in its original form.

4. Robert F. Burk, Never Just a Game (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 56. According to Burk, Athletics’ owners offered 80% of the gate share to the St. Louis Brown Stockings and Chicago White Stockings if those teams would come to Philadelphia to play the two final series of the season rather than have the A’s travel to their cities. Both clubs refused, and the Athletics then declined to make the trip, resulting in the latter being axed from the NL’s rolls.

5. David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball (New York: Donald I. Fine, 1997), 90, 103, 115, 127, 139, 157, 176. Nemec lists on those pages all of the teams that composed the NL each year between 1876 and 1882.

6. John Shiffert, Base Ball in Philadelphia (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2006), 41. He characterizes Athletics as “The first name in Philadelphia baseball.”

7. David Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League (New York: Lyons & Buford), 21.

8. Robert D. Warrington, “Philadelphia in the 1882 League Alliance,” Baseball Research Journal (Phoenix: SABR, Fall 2019), 105–24.

9. Shiffert, Base Ball, 113. The author writes, “The National League needed to muscle out some of its smaller franchise cities, and, more importantly, it needed the power and prestige of New York and Philadelphia to survive against the American Association.”

10. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1883/dec/

11. David M. Jordan, Occasional Glory: A History of the Philadelphia Phillies (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002), 6.

12. Donald Honig, The Philadelphia Phillies: An Illustrated History (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), 13.

13. Nemec, Beer and Whisky, 44.

14. “Baseball Matters,” The New York Times, September 25, 1882.

15. “Baseball,” The New York Times, September 26, 1882. According to authors Dewey and Acocella, the meeting was held in secret, and during the proceedings, Worcester and Troy were booted out of the League, and plans were laid to replace them with Philadelphia and New York. Donald Dewey and Nicolas Acocella, Total Ballclubs: The Ultimate Book of Baseball Teams (Toronto: Sports Media Publishing, Inc., 2005), 648. Worcester’s survival as a League member was tenuous from the very start. NL owners circumvented the League’s 75,000-person market requirement when approving the Worcester franchise—the city contained around 48,000 residents—by counting everyone within its five-mile territorial radius, not just the people within the city’s limits. The Worcesters’ finances were in dire straits during the 1882 season, and the League had to give the club a cash bailout so it could finish its schedule. Burk, Just a Game, 59, 72.

16. Warrington, “League Alliance,” 105–24.

17. Newspapers reported rumors emanating from NL sources as early as July, 1882 that Philadelphia would replace Worcester after the season. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, July 15, 1882.

18. Warrington, 105.

19. Shiffert, Base Ball, 237. According to the author, individuals before Reach had been paid to play baseball, such as Jim Creighton, but they were paid under the table. Reach was the first baseball player to openly accept a salary.

20. For a biographic sketch of Al Reach as a player, businessman and club owner, see, Rich Westcott and Frank Bilovsky, The Phillies Encyclopedia, 3rd edition (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004), 365–67. Another overview of Reach’s life and career in baseball is contained in Shiffert, Base Ball, 237–42.

21. Jordan, Occasional Glory, 6. Jordan notes that Reach’s “love of baseball” was one of the motivating factors in his decision to start a baseball club.

22. Frederick Lieb and Stan Baumgartner, The Philadelphia Phillies (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1953), 11–13. The authors portray a scene in their book in which Reach is approached by NL president Abraham G. Mills about owning the club that’s being moved from Worcester to Philadelphia. Reach eagerly replies, “I’m in!” Reach almost certainly wanted to become involved in the operation of a ballclub, but it’s highly unlikely he displayed the unrestrained enthusiasm to do so suggested by these authors.

23. Jordan, Occasional Glory, 6.

24. Francis C. Richter, “Rogers at Rest,” Sporting Life (Philadelphia: Sporting Life Publishing Company) Vol. 55, No. 2 (March 19, 1910), 5. This obituary of Rogers describes him as a “baseball magnate of local and national power.” Rogers’ significant influence in the city and state Democratic Party is addressed in the article, as is the major role he played in legally compelling players who “jumped” to American League teams in 1901 for fatter paychecks to return to the Phillies. Richter also notes that Rogers was Reach’s personal attorney when the two men invested in the Phillies in 1882. An unflattering biographic sketch of Rogers is contained in Shiffert’s book. The author writes, “Rogers was, with good reason, as big a problem to the team as Reach was an asset. Read any account of the Phillies’ first 20 years, and you’ll see adjectives attached to various aspects of (Rogers) and his career in Philadelphia baseball, adjectives like self-promoting, stubborn, arrogant, overbearing, enraged, litigious, bitter, mean-spirited, long-winded, meddler, suspicious, strident and manipulative.” Base Ball, 244–46.

25. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, October 7, 1882.

26. NL rules barred member clubs from playing non-NL teams within the territorial confines of another league city. Burk, Just a Game, 54–55.

27. Warrington, “League Alliance,” 111–12.

28. The Phillies were formally admitted to the National League at the League Convention on December 6, 1882. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, December 16, 1882.

29. Nemec, Beer and Whiskey, 44.

30. There is a widely held belief that when the Philadelphia Ball Club joined the National League its nickname was the Quakers. This is a misconception that can be traced to David Nemec’s book, The Great Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. The myth has been perpetuated on www.baseball-reference.com that states Quakers was the club’s nickname from 1883–89. As 19th century baseball historian Matt Albertson has written, “Nicknames were not official monikers used by major league teams until the 20th century. In the 19th century, nicknames were created and used by newspapers. In 1883 alone, the Philadelphia Baseball Club Limited was identified as “Philadelphias,” “Phillies,” “Quakers,” and even “Athletics.” The nickname “Phillies” itself is simply a shortened version of “Philadelphias.” His article was posted on March 13, 2019 on https://www.sportstalkphilly.com.

31. “League Victory in Law Would Mean Defeat on Field,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 29, 1901. The whereabouts of the original Phillies’ 1882 incorporation document is unknown. Fortunately, it was reproduced in the Inquirer 19 years later and is available to researchers.

32. Pratt’s nickname was “Dump,” although it was not associated with his baseball career. “The Old Sport’s Musings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 18, 1909.

33. Shiffert, Base Ball, 235–36.

34. Nemec, Great Encyclopedia, 214.

35. When not playing baseball, Pratt was part of the family-owned Pratt Bros., a paint and whitewash distributor and manufacturer in Philadelphia. The company’s success provided Pratt the funds to invest in the Keystones. Shiffert, Base Ball, 236.

36. “Notes,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 14, 1883.

37. “Baseball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 8, 1884. The Keystones’ won-lost record, place in the standings and games behind first place are in https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/PHK/1884-schedule-scores.shtml. It was also reported the Keystones would play out the season in the Eastern League. A check of www.baseball-reference.com shows no evidence the club ever joined the Eastern League. Like other members of the Union Association, the Keystones folded and did not make it through the 1884 season. https://www.retroseasons.com/teams/Philadelphia-keystones.com.

38. Nemec, Great Encyclopedia, 214.

39. The company is also referred to as the Central News Service in some newspaper articles.

40. “Charter Notices,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 25, 1904. In this notice of “intended charter,” the corporation is identified as the Union News Company Incorporated. Farrelly is listed as one of the officers in the company.

41. “Arraigned in Court,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 3, 1896. John O. Gallen, who lived adjacent to the Central News Company at 250 South Sixth Street, brought suit against the company asking the court to restrain it from moving or harnessing horses in its stable at the property between 10PM and 7AM. The company it was noted, runs many of its wagons and does most of its business in the small hours of the morning.

42. The location of Reach’s cigar store is identified in, Westcott, Phillies Encyclopedia, 366.

43. https://www.worldclasschicago.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Magazine-Preview.pdf.

44. For example, Walsh is referred to as the “owner” of the Cubs in, George Kibbe Turner, “The Forces Behind Taft,” McClure’s Magazine (New York: The McClure Publications) Vol. XXIX, No. 1 (May, 1912), 245.

45. That the club’s ownership details are unclear for the period is noted in, Jack Bales, Before They Were Cubs: The Early Years of Chicago’s First Professional Baseball Team (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2019), 244. For a list of Cubs’ owners from the first to the most current, see, https://www.mlb.com/cubs/history/owners.

46. Frank L. Hough, “Alien Owners,” Sporting Life, February 1, 1913, 12.

47. “The Old Sport’s Musings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 3, 1902.

48. Hough, “Alien Owners,” 12.

49. https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Syndicate_baseball.

50. Bill Lamb, John Day, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/john-day.

51. Dewey and Acocella, Total Ballclubs, 365.

52. Ban Johnson employed the same technique when establishing the American League. Charles W. Somers, a Cleveland coal baron, along with others, provided the financial backing for Johnson to inaugurate and sustain the League during its early years. Somers purchased the majority of stock in the Philadelphia Athletics initially. Then, Ben Shibe—ironically a partner in the A. J. Reach Sporting Goods Company— bought Somers’ shares to become the majority stockholder, owning 50 percent of the stock. David Jordan, The Athletics of Philadelphia: Connie Mack’s White Elephants, 1901–1954 (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1999), 12, 16. Hough writes that Somers came “across with the requisite capital until such time as arrangements could be made for exclusive local ownership” of American League clubs. “Alien Owners,” 12.

53. Jordan, Occasional Glory, 7–8.

54. “History of the Phillies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 25, 1909. Shiffert, Base Ball, 245.

55. The Athletics were among the most active clubs in purloining players from the NL’s ranks. Nemec, Beer and Whiskey, 44. The NL and AA “blacklisted” players who violated their contracts by “jumping” to another team. In the early 1883 “National Agreement” between the NL and AA, both leagues agreed to respect the contracts of each other’s players. Burk, Just a Game, 71–73.

56. Warrington, “League Alliance,” 123. Between 7,000-8,000 fans crowded into Recreation Park on May 22nd to watch the Phillies take on the visiting Athletics. No other Phillies’ home game in 1882 attracted more than 4,000 attendees. When the Phillies sold out, Reach was considerably annoyed by the fact hundreds of spectators would view the games from the roofs of houses surrounding Recreation Park. The homeowners would charge ten cents for a rooftop seat, vice the twenty-five-cent entrance fee for the ballpark. Reach had canvas screens stretched around the grounds and outside the ballpark during the 1882 season to block the view of the rooftop squatters, thereby ending the practice and depriving homeowners of additional income. “Stray Sparks From the Diamond,” New York Clipper, January 20, 1883. The situation was repeated in the 20th century when homeowners located on 20th Street opposite Shibe Park opened their rooftops to squatters to watch games. Like Reach, Connie Mack was irritated by the practice and had a 22-foot-high barrier of corrugated sheet iron erected on top of the existing 12-foot-high concrete rightfield wall, completely blocking the view from the 20th Street rooftops. Lawrence Ritter, Lost Ballparks: A Celebration of Baseball’s Legendary Fields (New York: Penguin Books, 1992), 180.

57. Warrington, “League Alliance,” 112–14.

58. Reach’s pursuit of sporting-related manufacturing opportunities was constant. In January, 1883, while in the midst of organizing the Phillies, his company introduced a tabletop version of cricket. It was described this way in the New York Clipper, “Table cricket is the name of a new Winter game for junior cricketers, which Al Reach of Philadelphia has just got out. It is somewhat on the principle of a miniature game of ball invented by Frank Sebring of the Empire Club of this city years ago, but is more complete in both the batting and bowling…It is a very ingeniously constructed game, and an enjoyable contest can be had with it on a dining-room table.” “Cricket,” New York Clipper, January 20, 1883.

59. Elias Mather, president of the Northwestern League also attended the meeting, invited at the behest of NL president Abraham G. Mills. Mills envisioned Mather’s role as an informal referent, helping to settle disputes when they arose during negotiations. Nemec, Beer and Whisky, 45–46.

60. Nemec, Great Encyclopedia, 191. The Association’s grudging acceptance of the 11-man reserve rule provoked furious objections from some quarters. An article in the New York Clipper stated the agreement “has awakened indignant protests from the press, public and players all over the country as being the old reserve-rule in a more virulent form.” The article predicted Association owners “will doubtless reject this clause as being most unjust and illiberal.” The owners went along with the change, however, and the rule remained in effect. The newspaper also reported there was “talk of professional players forming a protective association,” but nothing came of it at that time. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, March 3, 1883.

61. “The American Association Convention,” New York Clipper, December 23, 1882. In an interview in early 1883, Reach described in some detail the raw materials and production processes used “for making his patented ball.” He also observed, “A dozen men in the course of a day will turn out about twenty-five dozen first-class balls, and as a rule they make good wages.” New York Clipper, January 20, 1883.

62. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, February 24, 1883. Teams in the Interstate Association were called “American Alliance Clubs,” reflecting a relationship similar to League Alliance Clubs affiliated with the National League. “American Club Addresses,” New York Clipper, March 31, 1883.

63. The guide cost ten cents and was titled, “Reach’s Official American Association Baseball Guide.” It was printed by A.J. Reach & Company Publishers, and had the same address as his sporting goods business—23 South Eighth Street, Philadelphia. Advertisement in the New York Clipper, March 31, 1883.

64. Other official positions related to playing major league baseball games at Recreation Park had to be filled. One, for example, was official scorer. The distinction of being the first official scorer in Phillies’ history belongs to Henry H. Diddlebock. His appointment was announced in the New York Clipper, which reported, “Henry H. Diddlebock, a well-known journalist and attaché at the Tax Office of Philadelphia has recently been appointed official scorer of the Philadelphia Club for 1883.” “Baseball,” New York Clipper, March 31, 1883.

65. “The Philadelphia Club,” New York Clipper, January 13, 1883.

66. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, February 17, 1883.

67. Reach wrote in a letter to the New York Clipper that he had requested Anson’s assistance in identifying players for the Phillies. The newspaper published the letter. “Coleman and Ringo,” New York Clipper, January 27, 1883.

68. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/df8e7d29.

69. “Notes,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 3, 1882.

70. The players who were on the Phillies’ roster in 1882 are listed in an article about the club’s season that appears in the New York Clipper, January 13, 1883. Connor, Ewing, Gillespie and Keefe are listed as having been with Troy during the 1882 season in, Nemec, Great Encyclopedia, 182.

71. The Phillies’ 1883 roster can be found in, Westcott, Phillies Encyclopedia, 7–8.

72. Nemec, Great Encyclopedia, 182–83, 204–5.

73. New York Clipper, January 27, 1883.

74. Warrington, League Alliance, 110.

75. “A Base Ball Player Implicated in the Death of a Young Girl,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 7, 1882.

76. “Sudden Death,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 7, 1882.

77. Henderson was born on October 31, 1862. https://www.baseballreference.com/players/h/hendeha01.shtml.

78. Kathryn Hughes, “Gender Roles in the 19th Century,” British Library, May 15, 2014. https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/gender-roles-in-the-19th-century. For a list of the various definitions applied to the term “young girl,” see, https://www.thefreedictionary.com/young+girl.

79. https://www.glowm.com/section-view/heading/History of Contraception/ item/375#.Yg5tOpZOmuk. Pills advertised during the late 19th century as miscarriage-inducing included Dr. Monroe’s French Periodical Pills and Madame Drunette’s Lunar Pills. One study showed that women who took such pills experienced “violent pain in the abdomen, vomiting and powerful cathartic action…with heat and burning in the stomach, bowels, rectum and anal regions.” The study concluded the pills “could prove dangerous in the hands of desperate women.”

80. “Providence Pounders,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 4, 1883. Social vilification may have followed Henderson in the wake of Sarah McLaughlin’s death, and if so, probably convinced the Phillies and Henderson it would be best if he pitched elsewhere.

81. https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php?p=hendeha01.

82. “The National Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 25, 1882. Coleman had pitched for the Peoria Reds in 1882. The article noted, “Ringo is said to be one of the best pitchers in the country.” The sportswriter got the name wrong. Coleman was a pitcher and Ringo was a catcher.

83. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, January 20, 1883

84. New York Clipper, January 27, 1883.

85. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, February 10, 1883

86. New York Clipper, February 17, 1883. Ringo wrote a letter to the Clipper that was published in the February 24th, edition. In it, he stated in part, “Peoria cannot hold us, and we will certainly play for Philadelphia this season.”

87. “The Work of the Conference,” New York Clipper, February 24, 1883.

88. “The League Convention,” New York Clipper, December 16, 1882. As part of the settlement concluded at the February 17th convention, the NL and AA agreed to recognize the Northwestern League as a minor league, and by doing so, refrain from poaching players under contract from it. https://entertainment.howstuffworks.com/minor-league-baseball-team2.htm.

89. New York Clipper, February 24, 1883. If Coleman really wanted to play for the Phillies, then getting on the team was a pyrrhic victory. He lost 48 games in 1883, still the major league record for most defeats in a season for a pitcher. https://www.baseballreference.com/leaders/L_season.shtml.

90. New York Clipper, February 17, 1883.

91. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, March 24, 1883.

92. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, December 23, 1882.

93. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, March 17, 1883. Some of the article’s information about Fisler’s career is incorrect. He stopped playing in 1879, not 1878. In addition, he played 14 seasons for the Athletics (1866–79), not thirteen. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/f/fisler01.shtml. Part of Fisler’s appeal as a candidate for the roster is that he was a veteran. The Phillies probably believed his presence on the team as a mentor would be useful in maturing the multiple rookies who were likely to be in the lineup. Fisler, however, decided not to return to the diamond in 1883 or thereafter. New York Clipper, March 24, 1883.

94. Nemec, Great Encyclopedia, 204–5.

95. Teams traveling to Florida to prepare for the season started in 1888 when the Washington Nationals went to Jacksonville for preseason training. www.floridagrapefruitleague.com/home/history. The Phillies first trained in Florida the following year, also choosing Jacksonville for spring training camp. www.thegoodphight.com/2016/2/14/10977676/phillies-a-history-of-spring-trainingsites.

96. In a game between the Phillies and the amateur Five-Twenty Club, “the threatening weather kept many people away,” according to one newspaper account. “Another Easy Victory,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 7, 1883. The Phillies’ game against the amateur Foley Club “was stopped at the close of the sixth inning on account of the cold,” a newspaper reported. “A Game of Errors,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 1883.

97. “Burlesque Base Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 13, 1883.

98. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, November 4, 1882.

99. “Notes,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 13, 1883. When playing in the League Alliance in 1882, Philadelphia was permitted to charge only twenty-five cents for a ticket. In an interview in the New York Clipper offices on February 10, 1883, Reach acknowledged that now that the Phillies were members of the National League, the club would be obliged to charge fifty cents for a ticket—the League standard. He opined the higher ticket price would not hurt attendance at Phillies’ games. Reach added, “Fifty cents will give each person entrance to the ground, and a seat also in the grand-stand, while those that come late or prefer a seat elsewhere than in the grand-stand will be allowed a rebate equivalent to their car-fare to and from the ground.” “Baseball,” New York Clipper, February 17, 1883.

100. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, March 3, 1883.

101. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 13, 1883. Variable ticket pricing depending on the opponent was eventually embraced by baseball in the 20th century. The Colorado Rockies were the first club to introduce a sliding price scale in 1998, with tickets for games against “premium” opponents costing extra compared to those for games played against more pedestrian visiting teams. Other clubs followed suit in this practice. https://bleacherreport.com/articles/203152-all-baseball-games-might-be-premium-games.

102. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, April 7, 1883. Six additional exhibition games between the A’s and Phillies were scheduled after the season—October 1st, 6th, 8th, 11th, 13th and 15th. New York Clipper, March 3, 1883.

103. Nemec, Great Encyclopedia, 191.

104. New York Clipper, April 7, 1883. When interleague play started between the American League and the National League in 1997, the decision was made to use the AL’s designated hitter rule during games held at AL ballparks, and not to do so during games hosted at NL ballparks. In addition, for the three years of interleague play (1997–99), umpire crews for each interleague game came from the league where the game was being played. www.mlb.com/mlb/history/interleaue/index.jsp.

105. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, April 14, 1883.

106. https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Billy-McLean. McLean went on to umpire 345 games in the National League and American Association before retiring in 1890.

107. New York Clipper, April 7, 1883.

108. “The American Association Meeting,” New York Clipper, March 24, 1883. According to the newspaper report, “A rule was adopted that no American club shall play any outside clubs in New York or Philadelphia without the consent of the resident club.”

109. New York Clipper, April 7, 1883.

110. “Baseball in Baltimore,” New York Clipper, March 31, 1883.

111. New York Clipper, April 14, 1883. Recreation Park’s seating capacity is found in, Rich Westcott, Philadelphia’s Old Ballparks (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 11. Officials of the Merritt Club were indignant at the Athletics and threatened to leave the Interstate Association. Cooler heads prevailed, however, and the Merritts remained in the organization. They played three exhibition games against the Athletics— two in Camden on April 19th and 27th—and one at the Athletics’ ballpark on April 25th. They lost all three, but the defeats were softened by the knowledge gate receipts far exceeded those that could have been gained playing an amateur club on those dates. “Athletic vs. Merritt,” New York Clipper, May 5, 1883. “More Victims,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 20, 1883.

112. “Athletic vs. Philadelphia,” New York Clipper, May 5, 1883.

113. “Eight to One,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 17, 1883.

114. “Athletic vs. Philadelphia,” New York Clipper, April 21, 1883.

115. New York Clipper, April 21, 1883.

116. “Field Sports,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 16, 1883.

117. New York Clipper, April, 21, 1883.

118. Rob Neyer, “Two Distinct Periods of Gambling,” (January 7, 2004). https://www.espn.com/mlb/columns/story?columnist=neyer_rob&id=1702483.

119. A review of newspaper accounts of the five subsequent games in the Athletics-Phillies series did not contain any mention of gamblers or gambling being associated with the matches.

120. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, May 5, 1883.

121. A description of the new ballpark and some of the amounts spent to build it can be found in, New York Clipper, March 31, 1883. Only the game on April 7th had been originally scheduled to take place in Baltimore. The game on April 11th was later added to the schedule of games in the Monument City.

122. “Philadelphia vs. Baltimore,” New York Clipper, April 14, 1883.

123. The attendance figure is taken from, “Baseball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 9, 1883.

124. “The Game at Baltimore,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 12, 1883. Although the visiting team always bats first in contemporary baseball, in 1883, the teams flipped a coin for the option of batting first or second. In this case, the Orioles selected to bat first. Teams often did this because a baseball, which was kept in a game far longer than is the case today, was in prime condition in the top half of the first inning, giving batters the best opportunity to hit it soundly.

125. “The Opening Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 3, 1883.

126. “Another Victory,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 4, 1883.

127. “The Philadelphia Club’s Opening Week,” New York Clipper, April 14, 1883.

128. New York Clipper, April 14, 1883.

129. “A Good Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 14, 1883.

130. “The Auburns Beaten,” Philadelphia Inquirer. April 19, 1883. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, April 28, 1883.

131. “Notes,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 20, 1883. “Notes,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 1, 1883.

132. Nemec, Great Encyclopedia, 199–205. Pennant-winning Boston had a roster of 12 players; second-place Chicago had 11; and, third-place Providence had 14.

133. Great Encyclopedia, 197, 204–5.

134. Westcott, Phillies Encyclopedia, 8.

135. Nemec, Great Encyclopedia, 320.