Roberto Clemente: Baseball Rebel

This article was written by Robert Elias - Peter Dreier

This article was published in ¡Arriba! The Heroic Life of Roberto Clemente (2022)

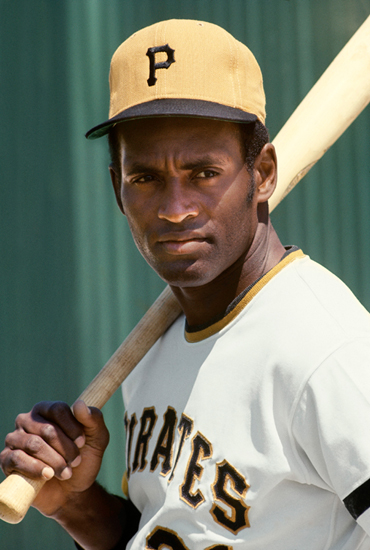

(Courtesy of The Clemente Museum.)

Robert Clemente was not the first Latino to play major-league baseball, but he was the first Latino superstar. He saw that as both a responsibility and an opportunity. Like Jackie Robinson, he used his athletic celebrity to speak out on behalf of social and racial justice. And like Robinson, he faced racism and pushback from owners, fans, sportswriters, and even some fellow players.

Clemente made his major-league debut in April 1955. Besides his solid hitting, he performed exceptionally on the basepaths and defensively in the outfield, routinely throwing out runners. Clemente introduced an exciting, rambunctious style of play, which endeared him to the fans but also made him more susceptible to injuries. In 1960 he was selected for his first of 15 All-Star Game appearances and helped lead the Pirates to the World Series and to their upset victory over the Yankees. Clemente won the first of his four batting titles in 1961 (with a .351 average) and an MVP Award in 1966. In 1968 he injured his shoulder and had such a hard time swinging the bat that he thought he’d have to retire. He rallied, however, making a comeback in 1969, hitting a NL second-best .345. In 1971 Clemente again led the Pirates to the World Series. He starred in the seven-game upset of the Baltimore Orioles, hitting .414, and winning the Series MVP. In 1972 Clemente reached 3,000 hits in his next-to-last game of the season, a feat surpassed by only 10 other major leaguers at the time.1 For his career, Clemente hit over .300 13 times and ended his career with a .317 average, 240 home runs, 1,305 RBIs, and 12 Gold Gloves.

Born in 1934 in Carolina, Puerto Rico, Clemente starred as an all-around athlete in high school. His arm was so strong that he became an Olympic prospect throwing the javelin. But he loved baseball and attracted the attention of Brooklyn Dodgers scout Al Campanis at a San Juan tryout in 1952. After an outstanding 1953 season with the Santurce Crabbers in the Puerto Rican League, the New York Giants and Milwaukee Braves offered Clemente a contract, but he signed with the Dodgers instead in 1954. Under rules at the time, Clemente received a signing bonus that required the Dodgers to keep him on their major-league roster or risk losing him in the offseason draft. Bonus players often just sat on the big-league bench when otherwise they could be gaining experience playing in the minors.

The Dodgers took a chance on losing Clemente by sending him to their Montreal Royals farm team in the International League for the 1954 season. The Royals put Clemente in the lineup for only 87 of their 155 games. Some argue that they did so to hide his skills from other clubs, especially the Dodgers’ archrival, the Giants, that might claim him at the end of the season. Others speculate that Clemente wasn’t elevated immediately to Brooklyn because they had a quota for Black players.

Clemente struggled initially in Montreal, but his performance improved by the season’s end. The Dodgers knew that the Pittsburgh Pirates – by then run by former Brooklyn general manager Branch Rickey – had their eye on Clemente. Dodgers GM Buzzie Bavasi struck a deal with Rickey (his former boss) to have the Pirates draft another player off the Royals roster. Since each minor-league team could lose only one player, Clemente would be protected. But the deal fell through and Clemente became a Pirate after all. In the offseason, Clemente returned to the Santurce Crabbers, joined by Willie Mays in the outfield. Clemente enjoyed a sensational season and the two players led the team to the Caribbean Series championship. Near the end of the winter season, an automobile accident damaged Clemente’s back. It would hinder him for the rest of his baseball career.

Clemente bristled over the racist way that sportswriters covered him. Clemente was frequently hurt and sometimes required surgery. He suffered damaged discs, bone chips, pulled muscles, a strained instep, a thigh hematoma, tonsillitis, malaria, stomach problems, and insomnia. Even so, between 1955 and 1972 he played more games than anyone in Pirates history.

Yet some sportswriters, teammates, and managers repeatedly accused him of being lazy or faking injuries if he missed a game. To the contrary, Clemente repeatedly played through pain, and excelled nevertheless. According to Pirates trainer Tony Bartirome, Clemente “… wasn’t a hypochondriac, he was a fighter.” When a White player pushed through injuries, he was regarded as a hero. “Mickey Mantle is God,” Clemente observed, “but if a Latin or black is sick, they say it is in his head.”2 Clemente fought constantly against negative stereotypes of emotional and lackadaisical Latinos.

The racism extended to the names the sportswriters used to identify him. They called him Bobby or Bob, instead of his preferred name, Roberto. Baseball card companies and other merchandisers followed suit even through the end of his career. White players were always asked what they wanted to be called. Sportswriters also made fun of his accent, quoted him in broken English, and paid little attention to his powerful intellect and social conscience. He knew little English when he joined the majors, and naturally spoke with a Spanish accent. After winning the 1961 All-Star Game for the National League, for example, Clemente was quoted as: “I get heet.… When I come to plate in lass eening … I say I ‘ope that Weelhelm [Hoyt Wilhelm] peetch me outside.…”3

Reporters corrected grammatical mistakes in English for White players all the time, but routinely made Latinos look ignorant, even a highly intelligent thinker like Clemente. The sportswriters thought nothing about not speaking Spanish themselves despite the growing presence of Latinos in major-league baseball.

Despite his stellar play for the Pirates’ 1960 World Series champions (.314 average, 16 homers, and 94 RBIs), he placed only eighth in the MVP balloting for an award bestowed on his White teammate Dick Groat. Given the racism he’d experienced throughout his time in the majors, he couldn’t help feeling that it influenced the voting. Clemente wasn’t a hometown favorite like Groat. Some baseball writers viewed him as brash and moody for speaking his mind, and speaking in Spanish. Clemente believed that Latino players like him didn’t receive the recognition they deserved, and he publicly complained about it.

Clemente played in the Puerto Rican League most offseasons, mostly for the Senadores de San Juan, which he also managed in 1964. He felt obliged to play for his Puerto Ricans fans. As Stew Thornley has noted, Clemente was “perhaps the most inspirational figure the island has ever known, and he took that responsibility seriously.”4

In the 1970-1971 offseason, he managed the Senadores again, competing against Santurce, managed by future Hall of Famer Frank Robinson. Both were top candidates to be the first Black manager in the major leagues, which Robinson achieved in 1975 with the Cleveland Indians.

Clemente was a proud Black man, Puerto Rican, and American. From 1958 to 1964 he served in the Marine Corps Reserve. Coming from Puerto Rico, a more racially integrated island, he was shocked by the segregation he encountered in mainland America, especially during spring training in the Jim Crow South. Black players on the Pirates during Florida spring training in the late 1950s and early 1960s couldn’t stay in the same hotels or eat in the same restaurants as their White teammates. While on the road, White teammates had to bring their food out to the team bus. Clemente refused to sit and wait on the bus. He demanded that the Pirates provide Black players with another vehicle so they could drive to Black restaurants where they would be served. He and other Black players were also excluded from the Pirates’ annual spring golf tournament at a local country club, while their White teammates participated.

During Clemente’s playing days, Pittsburgh had a large Black population but few Latinos.5 The prejudice against Latinos came not only from the fans and the media, but also his teammates, who used racial slurs when referring to Clemente and other Latino players. He occasionally confronted his bigoted White teammates. Clemente said, “I don’t believe in color; I believe in people. I always respect everyone, and thanks to God my mother and my father taught me to never hate, never to dislike someone because of their color. I didn’t know about racism when I got to Pittsburgh.”6 Nevertheless, the racism he faced turned “a mild, kind man into a blunt and angry one,” wrote biographer Mike Freeman.7

Clemente refused to be treated as a second-class citizen, repeatedly protesting Jim Crow segregation. When he encountered racism and stereotypes, he fought back vocally and visibly, even when that made him a bigger target. Clemente pushed back when a reporter called him a “chocolate-covered islander” or when sportswriters otherwise mocked him personally or questioned his abilities. He was confident of his abilities, insisting that “nobody does anything better than me in baseball.”8 Some Whites resented his directness but he demanded their respect.

As MLB.com columnist Joe Posnanski wrote, Clemente “… did rage. In this way, he was like one of his heroes, Jackie Robinson. He was unwilling to simply accept what he saw as injustice.”9 Clemente refused to remain silent. “You writers are all the same,” he shouted at one critical reporter. “You don’t know a damn thing about me.”10 Clemente didn’t want to merely represent Latin Americans; he wanted to improve their lives. He always said: “Remember who paved the way for you,” and he paid tribute to Puerto Rican pioneers in major-league baseball like Hiram Bithorn and Luis Olmo.11

According to his wife, Vera, Clemente talked “a lot about how being a black Latin coming into baseball meant you had two strikes against you. He wanted the Latino players to get their fair share of the money. He wanted them to be managers … to get respect.”12 According to Pirates trainer Tony Bartirome, Clemente saw his quest to improve things for the Latin and Black player as “his small way of changing the country for the better.”13

Clemente was angered by double standards. “When the sportswriters write about a black or Hispanic player, it’s always something controversial. When they write about white players, it’s usually nice – human interest stuff.” He liked to think he made some progress against that practice. “I believe that every human being is equal, but one has to fight hard all the time to maintain that equality. Always, they would say you’d really have to be something to be like Babe Ruth. But Babe Ruth was an American player. What we needed was a Puerto Rican player they could say that about, someone to look up to and try to equal.”14

In 1970, at Roberto Clemente Night at Three Rivers Stadium, Clemente declared: “I have achieved this triumph for us, the Latinos. I believe it is a matter of pride for all of us, the Puerto Ricans as well as others in the Caribbean because we are all brothers.”15

Clemente pushed the Pirates to hire more players of color and they listened. By the early 1970s, half the Pittsburgh roster was Black, Latino, or Spanish-speaking, and in 1971, for the first time in National or American League history, the Pirates fielded an all-Black and Latino lineup, thanks largely to Clemente.

Clemente played his entire career with the Pirates, from 1955 to 1972, during the peak of civil-rights activism. He closely followed the movement and identified with its struggles. He witnessed a speech Martin Luther King Jr. gave at a university in San Germán in February 1962.16 They later became friends. They met often, including a long visit on Clemente’s farm on the outskirts of Carolina, Puerto Rico, where they discussed King’s philosophy of nonviolence and racial integration. Clemente voiced these ideas both inside and outside the clubhouse. As teammate Al Oliver recalled: “Our conversations always stemmed around people from all walks of life being able to get along. He had a problem with people who treated you differently because of where you were from, your nationality, your color; also poor people, how they were treated.”17

King was assassinated in Memphis on Thursday, April 4, 1968, during the last week of baseball’s spring training. His funeral was scheduled for Tuesday, April 9, the day after opening day. Immediately, the NBA and NHL suspended their playoff games. Racetracks shut down for the weekend. The North American Soccer League called off games. But major-league baseball waffled. After many players sat out the last few games of spring training to honor King, several owners insisted that Commissioner William Eckert penalize them for refusing to play. But Eckert was more concerned about the start of the regular season.

Clemente was upset that Eckert announced that each team could decide for itself whether it would play games scheduled for Opening Day and the day of King’s funeral. Some team owners, torn over what to do, approached their Black players to feel the pulse of their employees.

In response, Clemente observed that “[i]f you have to ask Negro players, then we do not have a great country.”18

King’s murder triggered rebellions in a number of cities with major-league teams. Two teams, the Washington Senators and Cincinnati Reds, postponed their home openers because their stadiums were near the protests. But Houston Astros owner Roy Hofheinz, a businessman and former Houston mayor, insisted that his team would play its opener against the Pirates – the third game scheduled for April 8. “Our fans are counting on it,” explained Astros vice president Bill Giles.19 Under baseball rules, as the visiting team, the Pirates were required to play if the Astros wanted the game to go on.

On Friday, April 5, the next to last day of spring training in Richmond, Virginia, the Pirates players met in the hotel room of first baseman Donn Clendenon, who at King’s urging had attended Morehouse College and who taught school with King’s sister, to discuss what to do. The first meeting was attended by all 11 Black players (six of them also Latino), more than any other major-league team. At that meeting, veteran third baseman Maury Wills urged his teammates to refuse to play on Opening Day and the following day, when America would be watching or listening to King’s funeral.

The following day, all 25 players came to the meeting at the ballpark. The Black players explained that they had decided to boycott the two games. After Clemente urged his teammates to support Wills’ idea, they took a vote. They unanimously supported the idea. Clemente and Dave Wickersham, a White pitcher, contacted Pirates general manager Joe Brown and asked him to postpone the season’s first two games. The two players wrote a public statement on behalf of their teammates, which was included in the Pittsburgh Press story about the protest the next day: “We are doing this because we (white and black players) respect what Dr, King has done for mankind. Dr. King was not only concerned with Negroes or whites but also poor people. We owe this gesture to his memory and his ideals.”20 Clendenon and Willie Stargell walked into the Astros’ locker room and persuaded the Black players to join the protest. The other players agreed and informed the Houston brass: They would not play the first two games, until after King was buried.

St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Bob Gibson and some of his teammates had the same idea. They met in first baseman Orlando Cepeda’s apartment and then told Cardinals management that they wouldn’t play on April 9, Opening Day for most of the teams. Players on other teams followed their lead. The Los Angeles Dodgers’ Walter O’Malley was the last owner to hold out, but when the Phillies players refused to take the field against the Dodgers, his hands were tied. Commissioner Eckert, his back against the wall, reluctantly moved all Opening Day games to April 10. No sportswriter at the time described the players’ action as a strike. But that’s what it was – a two-day walkout, not over salaries and pensions, but over social justice.

Besides being concerned about racial injustice, Clemente was also a strong proponent of workers’ rights and labor unions. He played an important role in the battle to dismantle baseball’s reserve clause. He was the Pirates’ player representative to the Major League Baseball Players Association and a close ally of Marvin Miller, whom players hired as the union’s first executive director in 1966. Three years later, the St. Louis Cardinals traded their star outfielder Curt Flood to the Philadelphia Phillies. Flood didn’t want to move to Philadelphia, which he called “the nation’s northernmost southern city.”21 The Phillies offered him a $100,000 salary for the 1970 season, a $10,000 boost from his Cardinals salary. But for Flood, it was a matter of principle. He objected to being treated like a piece of property and to the reserve clause’s restriction on his (and other players’) freedom.

Flood talked with Miller about the possibility of suing in order to overturn the reserve clause. In 1922, in a case called Federal Baseball Club v. National League, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, which was intended to prevent collusion and monopolistic practices by business, did not apply to baseball. The court claimed that baseball was an “amusement” rather than a business engaged in interstate commerce, and thus was exempt from the federal antitrust law. The ruling allowed major-league baseball owners to operate as a monopoly, with teams colluding to deny players their right to bargain with prospective employers. Many scholars believed that this was one of the high court’s worst decisions, but it remained in force a half-century later.22 It was as if, Miller once observed, “the courts were saying, ‘Yes, you’re an American and have the right to seek employment anywhere you like, but this right does not apply to baseball players.’”23

Miller warned Flood that the odds were against him. He pointed out that a lawsuit would be expensive and could take two or more years. Moreover, Miller said, even if he won the lawsuit, he’d probably be unemployable in major-league baseball; the owners would blacklist him as a player and as a future coach or manager. Miller recalled, “I said to Curt, ‘Unless some miracle takes place and the Supreme Court reverses itself, you’re not going to win,’?and Curt, to his everlasting credit, said, ‘But would it benefit all the other players and future players?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ And he said, ‘That’s good enough for me.’”24

At the urging of Clemente, the players union held its annual executive committee meeting in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in early December of 1969. Miller invited Flood to the meeting at the Sheraton Hotel to seek the union’s financial and moral support for his lawsuit. Many of the players were skeptical of Flood’s idea to sue. After all, two previous legal challenges – by New York Giants outfielder Danny Gardella in 1949 and Yankees minor leaguer George Toolson in 1953 – had failed. Tom Haller, the Dodgers All-Star catcher, bluntly asked Flood if his decision to challenge his trade was based on race. “I didn’t want it to be just a black thing,” Haller recalled. “I wanted it to be a baseball thing.”25 Flood responded that while being Black no doubt made him more sensitive to injustice, he was doing this for all ballplayers, regardless of color.

The tide turned after Clemente spoke out on Flood’s behalf. He declared that Flood was the only player with the courage to take on the owners and the reserve clause. “So far, no one is doing anything,” he said.26

Clemente explained how as a minor leaguer he’d had turned down a much bigger bonus offer from the Milwaukee Braves because he wanted to played for the Brooklyn Dodgers. He was upset when the Dodgers allowed him to be drafted by the Pirates without any say in the matter because of the reserve clause. He would have preferred to play in New York, with its large Puerto Rican population, rather than Pittsburgh, a more racist city for Latinos. He even offered to refund the Pirates $4,000 in exchange for his freedom, but Joe Brown, the Pirates’ general manager, refused. “He had me,” Clemente told his fellow players on the union’s executive committee. He estimated that over his career with the Pirates, the team had “made $300,000 on me.27 Clemente no doubt lost lucrative commercial endorsement opportunities in the smaller and whiter Pittsburgh region.

Clemente was one of the few players on the executive committee who was earning at least $100,000.28 The players understood that Clemente – like Flood – was speaking on behalf of them, younger players, and future players. “Roberto was respected by everyone,” recalled Dick Moss, the MLBPA’s lawyer. “He was very important to us.”29

After Clemente spoke, Miller repeated his recommendation that the MLBPA support the lawsuit of their fellow player and union member. The players voted unanimously to back Flood’s lawsuit.30

Clemente once observed that: “If you have a chance to help others and fail to do so, you are wasting your time on this earth.”31 His activism went beyond fighting against racism and for players’ rights. Besides sponsoring philanthropies to distribute food, medical supplies, and baseball equipment, Clemente focused particularly on children. He routinely visited sick kids in hospitals and held frequent baseball clinics for low-income children. He campaigned to use sports to counter drug problems in Puerto Rico and elsewhere. Most ambitiously, he began building a Sports City in Puerto Rico, seeking to replicate it throughout the United States to provide athletics and counseling but also intercity and interracial exchanges to challenge all forms of discrimination.

A lasting bond between Clemente and the Nicaraguan people also began in the 1963-1964 offseason when Clemente played winter ball for the Senadores de San Juan, who represented Puerto Rico in the International Series in Managua, Nicaragua. Clemente became a fan favorite during the series, making many friends and pledging to return.

In 1971 West Point graduate Anastasio Somoza Jr., the third in a succession of US-backed Somoza dictators, canceled Nicaraguan Winter League baseball. However, the Nicaraguan national amateur team thrived. The following year, in front of euphoric home crowds in Estadio Nacional, the amateur team led by future major leaguers Dennis Martinez and Tony Chevez captured a bronze medal in the World Amateur Baseball Championships (WABC), including upsets over perennial champions Cuba and the United States. Those victories sparked national celebration. One of Nicaragua’s proudest and most memorable moments was upended three weeks later when a massive earthquake struck Nicaragua, killing nearly 10,000 people and destroying half of Managua.

Clemente had just been in Nicaragua, managing the Puerto Rican team at the WABC games and making more friends in the country, many of whom were poor and needed help. Back home in San Juan, he decided to help the recovery, using the media to organize a massive campaign of food, clothing, and medical assistance. Funded by Clemente, two cargo planes and a freighter began delivering the Puerto Rican aid. But soon word got out that Somoza was siphoning off the international aid flowing into Managua (including $30 million from the United States) and stockpiling it for his corrupt government. President Nixon dispatched a battalion of US paratroopers to Managua, which only further helped Somoza loot the country. Nixon claimed he didn’t want the earthquake to provide opportunities for communists.

Clemente learned that when a private American medical team arrived in Managua, it had to fight local Somoza officials from confiscating the supplies it brought. When Clemente discovered that Somoza was diverting other aid, he was enraged and vowed to personally deliver the relief he had gathered. Well-known and respected in Nicaragua, Clemente believed his presence would ensure that the aid would get to the people who needed it.

On December 31, 1972, the 38-year-old ballplayer boarded a broken-down and overloaded plane. Some warned him against making the trip, but he said, “[B]abies are dying. They need these supplies.” Claiming that “the people in charge know what they’re doing,” Clemente may nevertheless have suspected something was wrong with the plane, but said: “I have to go. I have to make sure everything’s okay in Nicaragua.”32 Several minutes after takeoff, the plane crashed into the Atlantic Ocean, killing Clemente and four others.

After Clemente’s death, Nixon proposed a Roberto Clemente Memorial Fund, even though the president’s support for the dictator Somoza and US foreign policy’s long-standing oppression of Nicaragua led directly to Clemente’s demise. In 1973 Nixon hosted the Clemente family survivors in the White House, posthumously bestowing the first-ever Presidential Citizen’s Medal on the fallen star. Clemente would have likely bristled at Nixon’s words: “The best memorial we can build to his memory is to contribute generously … to those he was trying to help … in Managua in Nicaragua, one of our friends to the south. [T]hat is the way Roberto Clemente would have wanted it.”33

As David Maraniss observed, Clemente became “universally loved and admired … but it wasn’t like that in his playing days.”34 It was “glorification after the fact.” Clemente’s memory was co-opted not only by Nixon, but by other politicians he would have likely despised, including George W. Bush (who posthumously awarded him the Medal of Freedom).

More genuinely, the Pirates retired Clemente’s number in 1973 and the Baseball Writers Association of America waived the normal five-year waiting period to elect Clemente to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973, the first Latino player ever inducted, if one excepts Ted Williams, whose mother was Mexican-American.35 The Office of the Commissioner established an annual Roberto Clemente Award (for community service) and a Roberto Clemente Day. In 1974 the Roberto Clemente Sports City opened in Puerto Rico and has since served hundreds of thousands of kids, including future major-league stars Juan González, Bernie Williams, and Iván Rodríguez. In 1998 the Sports City complex unveiled a bronze cenotaph, usually reserved for fallen military heroes, describing Clemente as “Son of Carolina, Exemplary Citizen, Athlete, Philanthropist, Teacher, Hero of the Americas and the World.” Clemente has been honored by dozens of schools, hospitals, coins, stamps, post offices, bridges, parks, housing developments, ballparks, streets, and museums in his name in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Nicaragua.

For all his posthumous veneration, Clemente was, as Maraniss has observed, “no gentle giant or saint” but instead a “fierce critic of both baseball and American society.”36 Clemente’s crusade should not be sanitized: “He ranks only behind Jackie Robinson among players whose sociological significance transcended the sport itself.” He raised issues that remain relevant and unresolved to this day. “With the nativist strain in American politics resurgent,” wrote Maraniss in 2016, “I wish Clemente were around to respond to … Donald Trump and those who promote fear based on geography and language and race.”37

ROBERT ELIAS is a professor of law and politics at the University of San Francisco. A longtime SABR member, he’s published many baseball essays, including the Octavius Catto bio for the SABR Biography Project. His dozen published books include five on baseball: The Empire Strikes Out, The Deadly Tools of Ignorance, Baseball and the American Dream, Major League Rebels, and Baseball Rebels. He’s now writing a baseball biography for the University of Pennsylvania Press entitled Danny Gardella: Post-War America and the Neglected Working-Class Hero to Today’s Millionaire Athletes. He recently joined in the Century Committee’s work on baseball and the Supreme Court.

PETER DREIER is the E.P. Clapp Distinguished Professor of Politics at Occidental College. He earned his BA in journalism from Syracuse University and his PhD in sociology from the University of Chicago, and has also worked as a newspaper reporter, community organizer, and senior policy deputy to Boston Mayor Ray Flynn. He is coauthor (with Robert Elias) of two new books, Baseball Rebels: The Players, People and Social Movements That Shook Up the Game and Changed America (University of Nebraska Press) and Major League Rebels: Baseball Battles Over Workers’ Rights and American Empire (Rowman & Littlefield). His other books include The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame (Nation Books), Place Matters: Metropolitics for the 21st Century (University Press of Kansas), The Next Los Angeles: The Struggle for a Livable City (University of California Press), and We Own the Future: Democratic Socialism, American Style (The New Press). His articles have appeared in Baseball Research Journal and NINE as well as in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, The Nation, American Prospect, Harvard Business Review, Perspectives on Politics, the Journal of the American Planning Association, Urban Affairs Review, New Republic, and other publications. He wrote the SABR profiles of Sam Nahem and Joe Black. He coauthored a 2018 report on working conditions at Disneyland, Working for the Mouse, and a 2022 study of working conditions among America’s grocery workers during the COVID pandemic, Hungry at the Table, both of which generated significant media attention.

Notes

1 Clemente did appear in one more game on October 3, 1972, in the ninth inning as a defensive replacement, but he did not bat.

2 Clemente Family, with Mike Freeman, Clemente: The True Legacy of an Undying Hero (New York: Celebra, 2013), 34.

3 David Maraniss, “The Last Hero, Roberto Clemente, Baseball’s Latin Legend,” Washington Post, April 2, 2006, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2006/04/02/the-last-hero-span-classbankheadroberto-clemente-baseballs-latino-legendspan/7c38584c-a70d-4ff1-9eea-1febd1c05402/.

4 Stew Thornley, Roberto Clemente (Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books, 2006), 56.

5 In 1960, Pittsburgh’s population of 604,332 was 83.2 percent White, 6.7 percent Black, and less than one percent Hispanic. Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung, “Historical Census Statistics On Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For Large Cities And Other Urban Places In The United States,” Washington, D.C. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, Working Paper No. 76, February 2005.

6 Matt Snyder, “Remembering Roberto Clemente, 40 Years After His Death,” CBSSports.com, December 31, 2012, https://www.cbssports.com/mlb/news/remembering-roberto-clemente-40-years-after-his-death/.

7 Clemente Family, with Freeman, Clemente, 58.

8 C.B. Ways, “‘Nobody Does Anything Better Than Me in Baseball,’ Says Roberto Clemente,” New York Times, April 9, 1972: SM38.

9 Joe Posnanski, “A Legacy Cherished: Remembering Roberto: Hall of Famer Synonymous with Heroism Thanks to Charitable Spirit, Baseball Feats,” MLB.com, December 28, 2017, https://www.mlb.com/news/roberto-clemente-s-legacy-still-resonates-c264059654.

10 Posnanski, “A Legacy Cherished.”

11 Mashkur Hussain, “The Great One,” The Ball Point, August 26, 2017, https://theballpoint.org/the-great-one-11985eb949c4.

12 Peter Dreier, “Athletes’ Racial Justice Protest Last Week Made History. But It Wasn’t the First Wildcat Strike in Pro Sports,” TalkingPointsMemo, September 3, 2020, https://talkingpointsmemo.com/cafe/athletes-racial-justice-protest-history-wasnt-first-wildcat-strike-pro-sports.

13 Clemente Family, with Freeman, Clemente, 35.

14 “Beyond Baseball: The Life of Roberto Clemente,” Smithsonian Institution (http://www.robertoclemente.si.edu/english/virtual_legacy.htm).

15 Roger Bruns, Finding Baseball’s Next Clemente: Combatting Scandal in Latino Recruiting (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2015), 79.

16 Kevin Blackistone, “‘More Than a Ballplayer’: After MLK Shooting, Roberto Clemente Halted MLB Opening Day 1968,” Washington Post, March 28, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/more-than-a-ballplayer-after-mlk-shooting-roberto-clemente-halted-mlb-opening-day-1968/2018/03/28/658f94b2-3289-11e8-8abc-22a366b72f2d_story.html.

17 David Maraniss, Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 220.

18 Blackistone, “‘More Than a Ballplayer.’”

19 John Florio and Ouisie Shapiro, “When King Died, Major League Baseball Struck Out,” The Undefeated, April 4, 2018, https://theundefeated.com/features/when-martin-luther-king-died-major-league-baseball-struck-out/.

20 Les Biederman, “Pirate-Astro Opener Delayed,” Pittsburgh Press, April 7, 1968.

21 Flood with Carter, 158.

22 Abrams, “Before the Flood”; Nathanson, “Who Exempted Baseball, Anyway?”; Mitchell Nathanson, interview with Peter Dreier, April 8, 2021.

23 Barra, “How Curt Flood Changed Baseball.”

24 Kevin Blackistone, “Baseball’s Hall of Fame Cannot Be Complete Without Curt Flood,” Washington Post, December 25, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/mlb/baseballs-hall-of-fame-cannot-be-complete-without-curt-flood/2019/12/23/68e9a526-25b7-11ea-ad73-2fd294520e97_story.html

25 Snyder, A Well-Paid Slave, 76.

26 Maraniss, Clemente, 231.

27 Snyder, A Well-Paid Slave, 79.

28 David Maraniss’s authoritative biography says that Clemente earned over $100,000 in 1969. But Baseball-Reference.com lists his salary that year as $45,000, although acknowledging that other sources indicate different salaries. Baseball Reference says he made $100,000 in 1970, so it is possible that he had signed a contract for that amount by the time of the December 1969 union meeting. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/c/clemero01.shtml.

29 Maraniss, Clemente, 232.

30 On June 19, 1972, the Supreme Court ruled against Flood by a 5-3 vote. Writing the majority decision, Justice Harry Blackmun admitted that baseball’s exemption from federal antitrust laws was an “aberration” but declared that it was up to Congress, not the court, to fix the situation. Miller found another way to dismantle the reserve clause. At the close of the 1975 season, he persuaded Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Andy Messersmith and Montreal Expos pitcher Dave McNally to refuse to sign contracts with their teams, claiming that they were free agents because the reserve clause should only apply for one year. The union had already won the right to a three-person board to hear all grievances. On December 23, 1975, the neutral arbitrator Pete Seitz ruled in favor of Messersmith and McNally, agreeing with Miller that owners didn’t have the right to perpetually renew contracts, that renewals could only be a one-time thing, and that players should be free to negotiate with another team.

31 “Roberto Clemente Quotes,” Baseball-Almanac.com, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/quotes/roberto_clemente_quotes.shtml.

32 Clemente Family, with Freeman, Clemente, 78.

33 Richard Nixon, “Remarks at a Ceremony Honoring Roberto Clemente,” The American Presidency Project (May 14, 1973), https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-ceremony-honoring-roberto-clemente.

34 David Maraniss, “No Gentle Saint: Roberto Clemente Was a Fierce Critic of Both Baseball and American Society,” The Undefeated, May 31, 2016, https://theundefeated.com/features/roberto-clemente-was-a-fierce-critic-of-both-baseball-and-american-society/.

35 Williams never publicly acknowledged his Latino heritage, but it may have made him sensitive to racial bigotry. In his Hall of Fame induction speech in 1966, Williams made a plea for adding Negro League players to Cooperstown. See Bill Nowlin, Ted Williams – The First Latino in the Baseball Hall of Fame (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2018).

36 Maraniss, “No Gentle Saint.”

37 Maraniss, “No Gentle Saint.”