Roberto Clemente and the Latino Ballplayer Experience

This article was written by Zac Petrillo

This article was published in ¡Arriba! The Heroic Life of Roberto Clemente (2022)

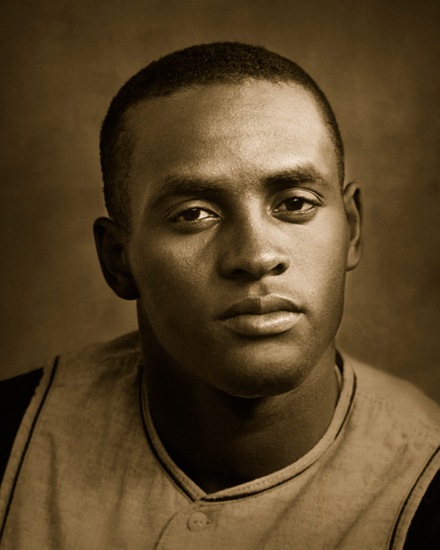

(Les Banos photograph courtesy of The Clemente Museum.)

About Roberto Clemente, Ozzie Guillén, the three-time All-Star shortstop, outspoken World Series-winning manager, and fellow Latin American, said, “He is the Jackie Robinson of Latin baseball. … He lived racism. He was a man who was happy to be not only Puerto Rican, but Latin American. He let people know that. And that is something that is very important for all of us.”1 Guillén, a native of Venezuela, captures what so many like him hold dear: Roberto Clemente, the man as much as the myth, emboldened all Latino ballplayers coming to America after him.

Clemente debuted almost exactly eight years to the day after Jackie Robinson first stepped on the field with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Between those dates, dozens of Black players signed with major-league baseball clubs and all but three teams were integrated. Clemente faced not only the still-present difficulties of being a Black man in a deeply segregated nation, he also was acclimating himself to a new environment, experiencing high expectations and off-base stereotypes.

“There was a largeness to Clemente’s persona that transcended baseball,” said historian Doris Kearns Goodwin.2 Like Robinson, representation and acceptance by Anglo United States only tells part of the story and, at times, reduces the complexities of the man. Clemente was full of contradictions, often belying the tidy version of an exotic Latin star that people, especially the media, wanted him to be. As such, he confronted both similar and uncommon issues compared with players who came before him, but his charisma and dominant play allowed him to pave a path to better prepare the many Latino superstars who followed.

The first Latino major leaguer was Colombian second baseman and outfielder Lou Castro, who debuted with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1902 and played in 42 games. The 1930s saw a small boom in Latino talent signing with major-league clubs, mostly out of Cuba. In 1934 Miguel Angel Gonzalez became a coach with the St. Louis Cardinals and four years later became the first major-league manager from that island nation. However, this representation was almost exclusively relegated to Cuban-born players and entirely for those with light skin.

It took until 1949 (47 years after Castro’s appearance) for a Black Latino player to take the field, when Minnie Miñoso pinch-hit for the Cleveland Indians against the St. Louis Browns. Miñoso played only nine games that season (16 mostly ineffectual at-bats) before being sent back to the minors, where he was kept until 1951. Feeling Miñoso wasn’t ready for the big leagues, Cleveland’s manager Lou Boudreau said, “He was a raw star in the beginning, but in only two years he was a seasoned ballplayer.”3 Still, speculation persists that the color of Miñoso’s skin played a part in keeping him in the minors longer than needed. He tore through minor-league pitching and once called up for good in 1951, he hit the ground running, swatting 10 homers and batting .326. He finished second in Rookie of the Year voting and became the first Latino star. A slew of Latino ballplayers followed Miñoso to the big leagues through the 1950s, including Clemente. While tolerance grew, stereotyping didn’t cease.

Clemente signed with the Dodgers in 1954, but the team had no intention of playing him; they wanted to avoid his talent landing with the crosstown rival New York Giants. Manipulating the international signing system is a practice that continues for Latino ballplayers decades later. In 1955, after being selected by the Pirates in the Rule 5 draft, Clemente told Pittsburgh broadcaster Sam Nover that a Fort Myers, Florida, newspaper said, “Puerto Rican hot dog arrives in town,” upon his arrival at spring training.4 Reporters routinely quoted Clemente with exaggerated phonetics. After Clemente smacked the game-winning hit off future Hall of Famer Hoyt Wilhelm in the 1961 All-Star Game, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette headline read, “I GET HEET, I FEEL GOOD.” In the article, Clemente is quoted: “I ‘ope that Weelhelm peetch me outside, so I could hit to right, but he peetch me inside.…”5 Clemente complained, “I never talk like that; they just want to sell newspapers.”6 Sportswriters also regularly referred to Clemente by pejorative nicknames such as “the dusky flyer” or the “lashing Latin” or the “chocolate-colored islander.”7 Clemente’s experiences were far from uncommon.

Pirates broadcaster Bob Prince leaned into Clemente’s Hispanic roots by creating the “¡Arriba! ¡Arriba!” signature call each time the right fielder did something spectacular on the field. It was a friendly play-by-play that helped endear both Clemente and his culture to the Rust Belt town. Pittsburgh fans took to it, commonly yelling, “¡Arriba!” at Roberto when he came to the plate or was spotted in public. However, the adoration, while meaningful to Clemente, did little to allay the effects of “othering” him, as he continued to feel dislocated culturally from most of his teammates. In 1960 Clemente believed he had a legitimate case to win the National League MVP Award, but writers not only placed him eighth overall, but behind three of his Pittsburgh teammates. Clemente believed the slight was because he was perceived as different and he never got over it.

In his superb Clemente biography, author David Maraniss explains that well into the right fielder’s time in Pittsburgh, he remained an outsider:

Roberto Clemente was indisputably an important member of the team, yet also in many ways alone. At the end of his sixth and finest season, he was still separated by culture, race, language, and group dynamics. He was the lone black player in the starting lineup and a Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican, while none of the sportswriters for the major dailies in New York or Pittsburgh were black or spoke Spanish. Life is defined by images, especially public life, and the Pirates image was that of a band of scrappy, happy-go-lucky, fearless, gin-playing, hard-drinking, crewcut, tobacco-chewing white guys. Where was the place in that picture for the proud, regal, seemingly diffident Roberto Clemente?8

After a game, a New York Giants broadcaster commented to Clemente that he “reminds [him] of another rookie outfielder who could run, throw and get those clutch hits. Young fellow of ours name of Willie Mays.” Clemente replied, “Nonetheless, I play like Roberto Clemente.”9 His “eccentric” tendencies remained a point of discussion, if also ridicule, in the press.

Sportswriters frustrated Clemente throughout his career. He never felt they saw his perspective and the constant stereotyping made him mad. On top of that, he was in a segregated country that told him where he could sleep and eat and even sit on a bus. Even though the word infuriated him, Clemente told author Roger Kahn he was a “double nigger,”10 expressing his feeling of ostracization from both White and Black culture in the United States. “I am black and Puerto Rican,” Clemente said. “I have to behave well. Perhaps I have more responsibility than others.”11

Writing about Minnie Miñoso, Latin baseball historian Adrian Burgos Jr. said, “[Miñoso] presents a quandary for many about where to place a black Latino within U.S. categories of identity: Is he black? Just Latino? Can he really be both?”12 Miñoso’s Cleveland teammate Harry Simpson, an African American from Georgia, accused him of “not being Black.”13 Vic Power, a Black Puerto Rican like Clemente, shared Clemente’s penchant for refusing to fit the mold of what Americans demanded of Latino ballplayers. He was gregarious, spoke out about injustice, and openly dated White women, a flagrant violation of 1950s racial sensibilities.14 In the early 1950s Power was outstanding in the minor leagues for the New York Yankees, the only New York team yet to integrate, but he was held back. Yankees general manager George Weiss said that “the first Negro to appear in a Yankee uniform must be worth having been waited for” and that Power was not the “right kind of Negro.”15 Power was traded to Philadelphia without ever playing for the Yankees.

In 1969 Clemente said to the press, “The farther away you writers stay, the better I like it.… Because you’re trying to create a bad image of me.… You do it because I’m black and Puerto Rican, but I’m proud to be Puerto Rican.”16 Clemente developed a reputation as a hypochondriac who exaggerated his injuries. “Sometimes when I wake up in the morning,” he once said, “I hurt so much I pray that I am still sleeping.”17 Clemente suffered from headaches, stomachaches, malaria, insomnia, tonsillitis, a hematoma in his right thigh, bone chips in his right elbow, a strained right instep, sore shoulders, and various pulled muscles. He freely talked about every ailment.18 His fellow countryman Power ribbed him for making up illnesses. He took the jabs in stride, but when the press teased him with the same barbs, he got incensed.19

The constant moans fueled stereotypes that Latino players were complainers and whiners, and didn’t take the game as seriously as their White counterparts. The perception only further galvanized Clemente to fight for his, and other Black Latino ballplayers’, rightful place in the game.

A deeply prideful man, Clemente’s stance against the media might’ve proved impactful toward getting fans to see him not only as a smiling construct, but as a human being. Instead, Clemente brought excitement to the ballpark and his connection with the fans was the one thing that never wavered. “He was our Jackie Robinson,” said Clemente’s friend and fellow Puerto Rican Luis Mayoral. “He was on a crusade to show the American public what a Hispanic man, a black Hispanic man, was capable of.”20

Clemente spoke out, often in Spanish, against the racial prejudices he faced in the segregated United States. He was especially vocal about the injustice of being separated from teammates during spring training in Florida, including Black team members being unable to attend a Pirates Welcome Luncheon commemorating the team’s 1960 World Series win. The only Black people allowed in were the waitstaff.21 He was fond of Martin Luther King Jr., even welcoming King for an afternoon at his farm in Puerto Rico. “Sometimes you have to understand there are bigger things than you, bigger things than the game,” said Carlos Delgado, a Black Puerto Rican whose path to major-league baseball was shaped by Clemente. “As an athlete, you have a platform with a lot of followers. You can push positive things; you can push movements and support movements.”22

Early in Clemente’s career, Black players were forced to stay on the bus after games while White players ate inside at roadside restaurants. The Black players had meals brought to them to eat on the bus once the others were finished. Clemente was so roiled by this process that he threatened to fight any Black player who tried to eat the meal. He pushed the Pirates to make better accommodations for Black players, which they eventually did, providing a separate means of transportation for them to get food.23 “I hope that we can continue the conversation, that we can tell future generations: ‘Look, this is Roberto Clemente. These are the values and integrity we want representing us,’” Delgado said.24 On September 1, 1971, Clemente was part of history when Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh penciled him into the third spot in the first ever all-Black starting lineup.

When Clemente first reached the US mainland, he roomed with Bob Friend, a pitcher who took him under his wing. The pair watched The Lone Ranger television show together which, along with other Westerns, helped Clemente pick up English. It’s a story told over and over for Latinos first coming to America. For example, when Miguel Tejada was assigned to the Medford A’s, alone and thousands of miles from the only home he knew in the Dominican Republic, he relied on Disney cartoons to help him pick up English so he could connect with his new community.25

In the time since Clemente played his last game, the major leagues have seen an explosion of talent from Latin American countries, with every team putting enormous resources into international scouting. By the 1990s, Latin Americans replaced African Americans as the second most prevalent demographic in the majors. In 2017 nearly 30 percent of all players identified as Latino.26 Clemente’s wife, Vera, continued her husband’s efforts to help Latin American talent by overseeing the Roberto Clemente Foundation as well as baseball clinics, including a “Sports City” complex in San Juan. Some successful major-league players who have gone through the system are Benito Santiago, Ruben Sierra, Juan Gonzalez, Carlos Baerga, both Alomar brothers, and Ivan Rodriguez.27

As detailed in Marcos Bretón and José Luis Villegas’s book about the journey of a Latino ballplayer, Away Games, this explosion “didn’t happen by accident.”28 With the advent of free agency in the mid-1970s, major-league teams scrambled to find talent as cheaply as possible. Felipe Alou, the major leagues’ first Dominican-born manager, said, “It’s like they throw a net in the ocean, hoping that maybe they’ll get a big fish. The problem is, if they don’t get a big fish, they’ll throw all the smaller ones back.”29 For every player who makes it to the big leagues, several more become undocumented men in a country not their own, forced into blue-collar jobs such as construction or must go back to the impoverished villages they came from.

In 1989 Puerto Rican-born players, as American citizens, became a part of the annual amateur draft, affording them much higher bonuses than players procured from other Latin countries. Just as manipulation surrounded Clemente’s signing, the process of scouting and signing international players has become fierce and detrimental to the many young men involved. In 2022 The Athletic dove into problems that persist around scouting of players from Latin American countries. Signing rules developed in 2017 limited the pool of money teams can allocate to talent. As a result, teams zero in on specific players, sometimes as young as 12 years old, so they may lock them up once they reach the allowable signing age. The report notes that use of performance-enhancing drugs is prevalent, especially among older players who have not yet secured a contract from big-league teams and risk falling behind if they don’t stand out.30

While baseball fans have come a long way in accepting Latin American players as an asset to the game, stereotypes still remain. In 2017 ESPN sports analyst Doug Gottlieb openly accused Dominican ballplayer Adrián Beltré, who continued to play at a Hall of Fame level well into his 30s, of using performance enhancing drugs. Gottlieb cited the fact that eight of the 13 players named in the Biogenesis PED scandal were Dominican.31 “Beltré’s from the Dominican Republic,” Gottlieb said. “Beltré (has) also been as or more productive into his mid- and now late-30s as he was in his 20s.”32

Gottlieb, like so many Americans, didn’t see Beltré as a human being who might operate independent of other Latinos, but instead as a stereotype who must represent the worst. It’s this exact type of thinking that Clemente largely broke down. After Clemente died, Puerto Rican writer Elliott Castro observed, “That night on which Roberto Clemente left us physically, his immortality began.”33 Yet what made Clemente so important was that he was every bit a mortal.

Clemente’s son Roberto Jr. recalled a story that encapsulates his father’s legacy, “Once, when I was in Pittsburgh, I stopped to help an old lady change a tire. She said, ‘Thank you, young man, where are you from?’ And I said Puerto Rico. And she said, ‘Puerto Rico! Why that’s where Roberto Clemente was from. He was a great man.”34 Clemente helped kids all around the world, but especially in Latin America, to understand they too could dream big. And dreaming big didn’t mean being perfect, it meant being themselves – battles with the press, headaches, tonsillitis, and all.

ZAC PETRILLO has a BA from Hunter College and an MFA from Chapman University’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts. He has directed multiple short films and produced shows for Comedy Central and TruTV. In 2016 he was instrumental in launching Vice Media’s 24/7 cable network, Vice TV. As a Society for American Baseball Research member, he focuses his work on post-1980s baseball and the intersection between the game and the media industry. He is currently the director of post-production at A+E Networks and teaches television studies at Marymount Manhattan College.

Notes

1 George Diaz, “Clemente 30 Years After His Tragic Death, the Influence of Baseball’s First Hispanic Superstar Is Stronger Than Ever,” Orlando Sentinel, March 31, 2002.

2 MLB, “MLB remembers the legacy of Roberto Clemente,” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KhWgUGbnko, December 17, 2017.

3 Lew Freedman, African American Pioneers of Baseball: A Biographical Encyclopedia (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2007), 286.

4 David Maraniss, Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero (e-book edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 358.

5 Maraniss, 774-775.

6 Adrian Burgos, Jr., “Left Out: Afro-Latinos, Black Baseball, and the Revision of Baseball’s Racial History,” Social Text, Vol. 98, Spring 2009: 47.

7 Steve Wulf, “December 31: ¡Arriba Roberto!,” Sports Illustrated, December 28, 1992.

8 Maraniss, 527-529.

9 Wulf.

10 Burgos, 47.

11 Burgos, 47.

12 Burgos, 45.

13 Burgos, 45.

14 Burgos, 46.

15 Burgos, 45.

16 Julio Ricardo Valera. “Time to Retire Roberto Clemente’s Number 21,” ESPN.com, July 11, 2017.

17 Wulf.

18 Wulf.

19 Maraniss, 705-707.

20 Wulf.

21 Maraniss, 741-742.

22 Jorge Castillo, “Remembering Roberto Clemente as a Black Man Who Fought Against Racial Injustice,” Los Angeles Times, September 8, 2020.

23 Maraniss, 736.

24 Castillo.

25 Alex Coffey, “Has Anybody Heard from Miguel Tejada Lately? Well, Yes, as It Turns Out,” The Athletic, June 22, 2020.

26 Federico Anzel, “MLB Demographics: The Rise of Latinos in Major League Baseball,” Visme Visual Learning Center, https://visme.co/blog/mlb-demographics/, 2018.

27 “Roberto Clemente Day Official in Puerto Rico,” Washington Post, August 18, 1993.

28 Marcos Bretón and José Luis Villegas, Away Games: The Life and Times of a Latin Baseball Player (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001), 39.

29 Bretón and Villegas, 40.

30 Marian Torres and Ken Rosenthal, “‘A failed system’: A Corrupt Process Exploits Dominican Baseball Prospects. Is an International Draft Really the Answer?,” The Athletic, January 20, 2022.

31 Marissa Payne, “Doug Gottlieb Accuses Adrian Beltre of Using PEDS, Partly Because He’s Dominican,” Washington Post, August 1, 2017.

32 Payne.

33 Maraniss, 1782.

34 Wulf.