Woody Smith: The Original Mr. Marlin

This article was written by Sam Zygner

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Sunshine State (Miami, 2016)

When you ask a Miami Marlins fan today, “Who is Mr. Marlin?” without hesitation you will get the response, “Jeff Conine,” who starred with the team for eight seasons. However, old-timers, who harken back to the days when minor league baseball ruled Miami, will give you a different answer: Woody Smith, a sure-handed third baseman with movie-matinee-idol good looks. Forest Elwood Smith was born on February 25, 1927, in University City, Missouri, to Roscoe Phillip Smith and his bride, the former Beulah V. Tessereau, who both hailed from the Farmington/Fredericktown area of southern Missouri. “Forry”, his given nickname, was the middle of three children; his older brother Roscoe Phillip Jr., known as “Pete,” was three years older and younger brother Jerry came along 17 years after Forest. They were all born and raised in University City, an inner ring suburb of St. Louis County.1

Young Forry stayed active driving a truck and making deliveries for the family’s dry cleaning business, running a paper route, attending church, and playing baseball whenever he could find the spare time. Jerry remembers his older siblings fondly, and how they seemed more like parents to him than brothers. “We were middle-class and both of the boys were in school and working jobs to help out.” He added, “I think they were both highly active in church and we had some people in our church that were professional athletes, or had been.” Mound City has always been a hotbed for baseball and the boys naturally gravitated to the sandlots to compete in pick-up games throughout the city.2

After finishing high school at University City High, Forest figured there were limited opportunities for him staying in the area, so he focused on two choices for his future: pursue a career in baseball or join the military like his older brother had. During World War II, Pete served in the Army in France.

Reggie (Forest’s son), remembers family stories about fate stepping in and how it changed the course of his father’s life. “He wanted to go into the Army, but dad was not allowed to go into the service because of a kidney infection.”3 Ultimately, he chose to play baseball. Jerry said of his brother, “Forry was pretty independent. He was driven and goal-oriented. Baseball didn’t find him; he found it.”4 With that, he began a journey that defined him the rest of his life.

Forest launched headlong into his new vocation and lifelong passion. He was originally signed as a pitcher by scout Jim McLaughlin to his first professional contract in 1946 with the St. Louis Browns organization.5 The wiry nineteen-year old was assigned to the Wausau Lumberjacks of the Class-D Wisconsin State League.6 Although his beginnings were inauspicious with a 4–3 record and a less than stellar 6.44 ERA, the Browns saw potential in the youngster. He made a dramatic improvement his sophomore season with the Ada Herefords of the Class-D Sooner State League, dominating the opposition, leading the league in wins (23–7), and ERA (2.00). He also batted .286 in 140 at-bats.7

The 1948 season proved to be one of both frustration and great joy. Not only was Smith reassigned four times that year, bouncing between Aberdeen, Hannibal, Muskogee, and Springfield, having worked 265 innings the year before in Ada, he came down with a sore arm and spent considerable time off the field with a bum wing.8 Nevertheless, away from the playing field he presented another type of diamond to the joy of his life, his bride-to-be, June A. Oswald. They exchanged nuptials on September 24 in St. Louis, the beginning of 56 years together.9 In 1949, rested and ready to return to full-time play, Smith was designated for assignment to the Gloversville-Johnstown Glovers of the Class-C Canadian-American League. There Forest met new player/manager and regular third baseman James Cullinane, who would have a profound effect on his career. His new skipper immediately assessed Forest’s hitting and fielding abilities and saw that his career path was better suited at the far corner of the infield versus toiling on the mound. Cullinane, known for his fielding prowess, would set a Can-Am League record that same year by collecting 308 assists.10 Smith continued to take the mound for the Glovers while Cullinane took him under his wing and tutored him in the finer points of hitting and fielding. Smith struggled (10–7, 4.99, 128 IP) on the mound, yet despite his inconsistencies on the hill, under the tutelage of his mentor he began to learn the intricacies of playing third base during off time, while playing outfield and first base part-time between pitching assignments. He impressed Cullinane by batting a glossy .324 and collecting 29 RBIs in 216 at-bats.11

By 1950, Cullinane was in the midst of his last season of professional baseball and yielded his playing time to Smith who took over as the Glovers’ regular third sacker. Not only was his performance at his new position extraordinary, Forest was effective with the bat, hitting .288 with 13 home runs in 137 games.

From 1951 to 1955 Smith continued to climb up the minor-league ranks. He was acquired by the independent Class-B West Palm Beach Indians of the Florida International League in the spring of 1951, and his performance caught the eyes of several major-league organizations. Serving as the club’s everyday third baseman, he bashed an impressive .320 and finished the year only 12 points behind league-leading hitter, Ted Cieslak.12

It was with the Indians that his new nickname “Woody” appeared in the press. In interviews with family members it is unclear how he acquired his nickname, but his brother Jerry surmised it most likely derived from his middle name of Elwood, or in connection with his first name.

He once again found himself changing organizations, having been acquired by the New York Yankees prior to the 1952 campaign. He was assigned to the Beaumont Roughnecks of the Double-A Texas League where he turned heads with his flashy glove work all the while batting .281 in 117 games. He earned a promotion to the Kansas City Blues of the Triple-A American Association in 1953 and led all third basemen in the league in double plays turned with 31, and tied for the league lead in assists with 288.13 In 1954, the Yankees were high on 23-year old prospect Kal Segrist Jr., so there was little playing time for Smith. Yankees brass decided to assign Woody to their other Triple-A affiliate in Richmond, Virginia, and after a very brief stay he was optioned to the Philadelphia Phillies Triple-A affiliate, the Syracuse Chiefs of the International League, where he regained his everyday position.

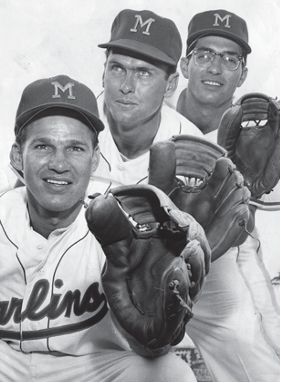

Infield anchors of the 1956–57 Marlins: Smith, Micelotta, Tompkins (left to right). Woody Smith receiving his 1959 Rawlings Silver Glove Award and shaking hands with team owner George B. Storer. (Miami News Collection, HistoryMiami)

Smith returned to the Yankees in 1955, this time with the Denver Bears of the American Association. Finding little playing time again, he was sold to the Charleston Senators. Although Smith excelled with the glove and bat, the Senators struggled to a league worst 50–104 record. Woody would soon find himself packing his bags again, and in December of 1955 was sold to the Havana Sugar Kings of the International League. However, his stay would be brief. The newly minted Miami Marlins, a Philadelphia Phillies affiliate owned by Sid Salomon Jr. and headed up by baseball maverick Bill Veeck, were looking to make a splash in the minor-league market. Veeck had already made a blockbuster move when he signed the ageless wonder Leroy “Satchel” Paige not only as a gate attraction, but as an effective swingman on the mound. With the goal of winning a pennant in their inaugural season Veeck sought to improve his team by any means. One of the team’s glaring weaknesses was at third base where 38-year old Sid Gordon, a 13-year major league veteran famous from his days with the Boston/Milwaukee Braves, New York Giants, and Pittsburgh Pirates, held down the job at the hot corner. Although Gordon was adequate with the bat, he had slowed down to the point of having very little range at his position. On July 26, 1956, Veeck, who had his eye on Smith since the beginning of the season, pulled the trigger and purchased the slick gloveman from the Sugar Kings for $15,000. According to Greg Mulleavy, manager of the Montreal Royals, Smith “didn’t like Havana and told me at the all-star game in Toronto that he wasn’t going back there next year.”14 In an interview with Luther Evans of the Miami Herald, Smith enthusiastically said, “…golly would I like to play for this club.” Woody found a new home and would settle into his position for the next four and half seasons.15

Smith debuted on the night of July 26, 1956, in front of 5,658 rabid fans at Miami Stadium, and it was a night to remember. When his name was announced for the first time the crowd answered with thunderous applause. The evening was an auspicious beginning as he accepted four chances at third without an error and collected four singles and a base on balls in five plate appearances, helping the Marlins defeat the Toronto Maple Leafs 4–3.16,17

Woody’s presence solidified the infield, teaming up with shortstop Mickey Micelotta, second baseman Benny Tompkins, and first baseman Ed Bouchee. This combination would stay intact through the end of 1957, with the exception of Bouchee who was replaced by Francisco “Pancho” Herrera in 1957.

Spurred by Smith’s arrival, Miami surged into first place temporarily on July 29, when they split a twin bill with Montreal, while the Toronto Maple Leafs dropped a nail-biter to Havana, 2–1. On the day Smith went three for five in the first game helping Paige earn the victory, and three for four in the second tilt, including two doubles. One double seemed to be Smith’s first home run for the Marlins, but it was overruled by the umpiring crew. This drew the consternation of Marlins manager Don Osborn, who felt the ball had deflected off the light tower in left-center field, not the fence, making it a homer.18 The Leafs escaped the inning unscathed and won a game they would have lost with a different call.

Smith’s season continued to be eventful. He played in one of the most famous games in minor-league history, the Orange Bowl Game on Tuesday August 7, 1956. The Marlins squared off against the Columbus Jets and played inside the world-famous football stadium. The field was especially configured to accommodate baseball. Veeck, with the intention of breaking the minor league record for attendance, arranged to use the Orange Bowl and surrounded the event with special promotions, pomp, and circumstance including performances by singers Cab Calloway, Margaret Whiting, and the Russ Morgan Band, among others. He called on Satchel Paige to take the mound in front of 57,713 fans.19 For his part, Smith had one base knock in three at-bats and drove in one run on a sacrifice fly in the 6–2 Marlins win.20

Although Miami (80-71) ultimately faded to a third place finish in 1956 and were eliminated in the first round of the Shaughnessy playoffs by the Rochester Red Wings, Smith’s year was a successful one as he finished with 19 home runs, 83 RBIs, and a .267 batting average.

Over the next four seasons the “Fish” as a team failed to put together another winning campaign, yet Smith held down his usual position with aplomb, batting .277 with 14 home runs and 73 RBIs in 1957, .291 batting average, 13 home runs, and 79 RBIs in 1958, and .274 batting average, 16 home runs, and 78 RBIs in 1959, before slumping in 1960 to a mere .213 batting average with only 49 RBIs, though with 11 home runs.21 Smith was named team’s most valuable player from 1957–59 and was widely regarded as the team’s most popular player. In 1958, he was awarded a Rawlings Silver Glove for his defensive prowess, one of the awards he was most proud of during his career.22 The trophy was given each year to nine members (one at each position) comprising every team and its players in the National Association based on their official final fielding average.23 That same season he broke the International League record for consecutive games without an error at third base, 86 straight, smashing the old record of 56 set by Irvine Jeffries of the 1937 Montreal Royals.24

Woody Smith receiving his 1959 Rawlings Silver Glove Award and shaking hands with team owner George B. Storer. (Miami News Collection, HistoryMiami)

Although the inaugural season in Miami, under the guidance of Veeck, had been a successful one, interest in the club soon waned. By 1960 the third owner of the Marlins, Bill MacDonald was taking heavy financial losses that were attributed to a less than satisfactory stadium lease agreement and sagging attendance. On September 11, 1960, Miami played their last game against the Richmond Virginians on the road. In the abbreviated game that was ultimately called after five innings due to a torrential downpour, Woody homered in his last at-bat as a Marlin in what proved to be the game winner.25 Just as he had come in with a bang, he left in the same way.

For all his outstanding efforts, one of the great mysteries to fans and teammates was why the Philadelphia Phillies never called Woody up to the big leagues. In a 2010 interview, Tommy Qualters reminisced about his teammate and how he was mishandled by the Phillies, “Yeah, Woody Smith, I’ll tell you a little story about him. He was probably the best defensive third baseman you could ever see. He was unbelievable.” He added, “So he had come to spring training…We just needed a body and there was no chance he was going to make the team. And it was just obvious. I don’t know what the hell they were thinking. They just didn’t treat him right. They just didn’t show any interest in him at all and he just packed his stuff and went home. Well, Roy Hamey was the General Manager and he black-balled Woody.”26

The Baltimore Orioles took over the Miami affiliate prior to the 1959 season, and ended their working agreement at the close of the 1960. In 1961 Miami did not host a minor league team, and so Smith was signed by the Minnesota Twins and assigned to their Triple-A affiliate in Syracuse, New York. It was the 35-year old veteran’s last season as a regular player before he closed out his career with the Rochester Red Wings, appearing in 10 games in 1962.

In 1969, Smith made a triumphant return to the city where he was so esteemed. Miami, now a member of the Class-A Florida State League, was being run by general manager Bill Durney Jr., under the tutelage of his father Bill Durney. The elder Durney worked for the club in various capacities dating back to the original Marlins in 1956, Bill Jr., had learned the ropes starting out as a ballboy, then pitched batting practice, and eventually was promoted to a front office position. The youthful GM had been mostly compliant with the Baltimore Orioles when it came to who was assigned to the club as its manager, but when he saw the opportunity to bring Smith back to Miami, he was insistent with the parent club’s vice president Harry Dalton that Woody was their man for the manager’s vacancy. Durney Jr. exclaimed, “Since Woody was certainly the acquisition we wanted, and it came down to the very end when they hired him, because we were really pushing for him. And I think they had someone else in mind.”27

With Smith at the helm the Miami Marlins/Orioles reeled off the most dominating stretch in Florida State League history.28 From 1969–72, the club won four straight division titles and four straight league championships, compiling a combined record of 335–201.29 Going back to 1919, no other FSL city has won more than two consecutive league titles.30 Under Woody’s watchful eye, players like Don Baylor, Rich Coggins, Jim Fuller, Kiko Garcia, John Montague, Mike Reinbach, and Tom Walker, just to name a few, climbed the ladder to the big leagues.

During the fall of 1972, after four years of unprecedented success, Smith got a phone call from Baltimore Orioles Director of Player Development, Don Pries at his home in St. Louis to set up a meeting at the airport. June, his wife remembered, “So, Woody was all excited…he just thought oh gosh he’s getting a promotion…And so he went to meet Don and after about an hour or two he came back, he walked in, and I said, ‘What happened?’ He said, ‘I got fired.’ According to June, the reasons given by Pries were that they did not have any place for him to move up or down since managers Cal Ripken Sr. and Joe Altobelli were at the higher levels and they hated to ask him to come back for a fifth season. It was a shock to Smith who had done everything the Orioles had asked of him.

Woody remained resilient despite his disappointment. “He was never bitter, or that upset over being let go that year,” declared June. “He was at the very first when he was let go after four years after he won four pennants. People would think he would be terribly upset, but he went right on.”31

And move on Woody did, managing the Key West Conchs during the 1973 season. He gained some measure of satisfaction by beating his old team on opening day in the Keys, 7–6. He and his team traveled the next night to Miami’s home opener in Miami Stadium to what the Miami Herald described as being like “Woody Smith Night.” The 1972 championship banner was raised and Smith was honored by the North Shore Kiwanis Club with a plaque for outstanding achievements. He was met with wild applause from the 4,177 fans that turned out to honor their hero. It must have felt odd to the many in attendance to see Smith sporting a big KW on the front of his ballcap.32

After the close of the 1973 season, Woody was hired by the Cleveland Indians and moved on to manage at San Antonio of the Texas League for two years (1974–75), Waterloo of the Midwest League (1977–78), and Chattanooga of the Southern League (1979–81). In his first year in San Antonio, Woody managed Dennis Eckersley, who went on to a Hall of Fame career.33 He also served as the Midwest Scouting Director for the Tribe from 1981 through 1987, and also worked in the same capacity with the California Angels from 1988–90 before retiring that same year.

Sadly, later in life Smith struggled with dementia. Although physically he was still a strong man, his mind deteriorated to the point that many of his baseball memories would no longer come to him. Finally, On February 4, 2005, Forest Elwood “Woody” Smith succumbed to natural causes leaving behind his wife June and sons Woody Jr. and Reggie, and daughter Gale.

Woody’s greatest legacy was not only that he was a great player and manager, but also a person who left a positive impact on his friends, family, teammates, and players who had the opportunity to share the playing field with him. Lenny Scott, a pitcher who played under Smith from 1970–72, described his skipper:

Oh, he’s the manager’s man…He knew how to talk to you. You know he didn’t talk at you…He knew how to bring things to the table. He had a lot of hardship. You know Woody would be out on the field practicing while we was out there practicing taking ground balls, and he would talk about the opportunities. And doing whatever you got to do, and take the opportunities and take advantage of it, right. But, he never got that opportunity and I could never understand it. He was a very delightful man. Very knowledgeable about the game and he was a very knowledgeable guy.34

June remembered Woody always saying, “I was their manager, their teacher, and a father to those 25 kids. They would bring me all of their troubles into my office and I would talk to them.” Then he said, “I had to go on to the field and instruct every one of them. I mean you had to know everything.”35

Earl Hunsinger, pitcher and teammate of Woody’s on the 1957 Miami club, put it best: “Woody was not only the favorite of the players but of the fans too. Woody was very outgoing, hustled all of the time, and never slacked up. He was a third baseman and I’ll never forget, you know after each groundout you used to throw the ball around the infield. The third baseman always throws it back to the pitcher. And Woody, when he threw the ball back to you, always had something good to say. He was quite a gentleman.”36

SAM ZYGNER is the author of the book The Forgotten Marlins: A Tribute to the 1956–1960 Original Miami Marlins. He has been a member of SABR since 1996 and is the Chairman of the South Florida Chapter of SABR. He received his MBA from Saint Leo University. His writings have appeared in the Baseball Research Journal, The National Pastime, NINE: A Journal of Baseball History & Culture, and La Prensa de Miami. A lifelong Pittsburgh Pirates fan, he has shifted some of his focus to Miami baseball history.

Acknowledgments

My sincere appreciation to the Smith family; Jerry, Reggie, Gale, and June for sharing their experience. Thank you to HistoryMiami for providing photographs. I am grateful to Bill Durney Jr., Earl Hunsinger, Tom Qualters, and Lenny Scott for imparting their thoughts on Woody Smith. And last, but not least, I am indebted to my wife Barbra who supports me in all my writing endeavors and who always inspires me.

Notes

1. Ancestry.com and Jerry Smith, phone interview, January 6, 2016.

2. Jerry Smith, phone interview, January 6, 2016.

3. Reggie Smith, phone interview, December 4, 2015 and March 2, 2016.

4. Jerry Smith, phone interview, January 6, 2016.

5. Information located by son Reggie Smith in family records.

6. Baseball-Reference.com.

7. Peter G. Pierce, Baseball in the Cross Timbers (Oklahoma Heritage Association, Oklahoma City, OK 2009) 205, 341.

8. Baseball-Reference.com. Reggie Smith passed on personal information given to him by his father who told him that the 1948 season was disappointing because of his struggles with an arm injury.

9. Ancestry.com.

10.. John L. Halpin, “Steve Salata Top Fielding Catcher In Cam-Am,” Oneonta Star, January 20, 1950, 10.

11. Sporting News Baseball Guide and Record Book, 1950, 286–89.

12. Baseball-Reference.com.

13. Ibid.

14. Jimmy Burns,” Marlins Deaf to First-Year Pennant Warning by Betzel,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1956, 28.

15. Luther Evans, “Marlins Buy New Infielder: Smith,” Miami Herald, July 26, 1956, 1-D.

16. The Sporting News, August 8, 1956, 27.

17. Luther Evans, “Marlins Chill Leafs on Walk in 9th,” Miami Herald, July 27, 1956, 1-D.

18. Eddie Storin,” Marlins Split, But Grab Lead,” Miami Herald, July 30, 1956, 1-D.

19. Norris Anderson, “Marlins Claim Record 51,713 See 6–2 Victory,” Miami News, August 8, 1956. The official record was noted by The Sporting News as 57,713, which was acknowledged as the minor league record that the Denver Bears broke in 1980.

20. The Sporting News, August 15, 1956, 30.

21. Baseball-Reference.com.

22. Clifford Kachline, “Rookie In Class D Crashes All-Star Minor Glove Team,” The Sporting News, December 10, 1958, 14.

23. The Sporting News, October 1, 1958, 51.

24. Norris Anderson, “Smith’s I.L. Fielding Record Verified,” Miami News, July 18, 1958.

25. “It’s All Over Now for Marlins,” Miami News, September 12, 1960.

26. Tom Qualters, phone interview, March 5, 2010.

27. Bill Durney Jr., phone interview, July 19, 2014.

28. The franchise was referred to as the Marlins in 1969 and 1970, and the Orioles in 1971 and 1972.

29. Baseball-Reference.com.

30. Milb.com. Florida State League Champions. The cities that have won back-to-back championships are DeLand 1951–52, St. Petersburg 1966–67, Lakeland 1976–77, and Tampa 2010–11.

31. June Smith, phone interview, September 22, 2014.

32. Luther Evans, “7–2 Home Opening Win,” Miami Herald, April 19, 1973, 1-C.

33. Baseball-Reference.com.

34. Leonard Scott, phone interview, August 25, 2015.

35. June Smith, phone interview, September 22, 2014.

36. Earl Hunsinger, phone interview, March 15, 2010.