The Fall of the Big Red Machine, 1976-1981

This article was written by Anthony Giacalone

This article was published in 1975 Cincinnati Reds essays

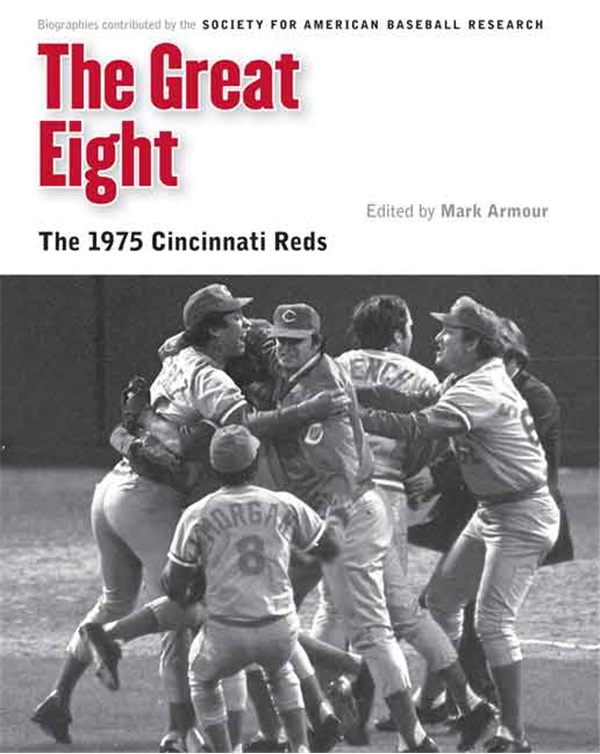

The Big Red Machine reached its destiny when Cesar Geronimo closed his glove around Carl Yastrzemski’s fly ball on October 22, 1975 at Fenway Park to end the World Series. In that moment of ecstasy and exhaustion the Cincinnati Reds became world champions, finally grasping the ring that had eluded their reach in the first half of the decade. On a cold October night, in Yankee Stadium, nearly one year later, after another brilliant campaign, they successfully defended the title. But then it was over. And while the Reds Empire didn’t exactly fall in the second half of the 1970s, it did stumble.

The Big Red Machine reached its destiny when Cesar Geronimo closed his glove around Carl Yastrzemski’s fly ball on October 22, 1975 at Fenway Park to end the World Series. In that moment of ecstasy and exhaustion the Cincinnati Reds became world champions, finally grasping the ring that had eluded their reach in the first half of the decade. On a cold October night, in Yankee Stadium, nearly one year later, after another brilliant campaign, they successfully defended the title. But then it was over. And while the Reds Empire didn’t exactly fall in the second half of the 1970s, it did stumble. There are several reasons why the Reds failed to reach the summit again after 1976. First, the contenders for the crown were very powerful. Additionally, some the team’s old warriors were sent away or allowed to leave, while age and injury slowed the skills of some who remained. Finally, the Reds failed to modernize, allowing their opponents to strengthen their legions while the Cincinnatians grew weaker. So, despite six years of valiant battling, by 1982 the Reds dynasty lay in ruins, a victim of miscalculation and cruel fate.

The Big Red Machine reached its destiny when Cesar Geronimo closed his glove around Carl Yastrzemski’s fly ball on October 22, 1975 at Fenway Park to end the World Series. In that moment of ecstasy and exhaustion the Cincinnati Reds became world champions, finally grasping the ring that had eluded their reach in the first half of the decade. On a cold October night, in Yankee Stadium, nearly one year later, after another brilliant campaign, they successfully defended the title. But then it was over. And while the Reds Empire didn’t exactly fall in the second half of the 1970s, it did stumble. There are several reasons why the Reds failed to reach the summit again after 1976. First, the contenders for the crown were very powerful. Additionally, some the team’s old warriors were sent away or allowed to leave, while age and injury slowed the skills of some who remained. Finally, the Reds failed to modernize, allowing their opponents to strengthen their legions while the Cincinnatians grew weaker. So, despite six years of valiant battling, by 1982 the Reds dynasty lay in ruins, a victim of miscalculation and cruel fate.

Having built the Reds into champions, the team’s longtime general manager Bob Howsam looked to improve his world-champion squad. In an effort to give the team more vitality and versatility, after the 1975 season, Howsam dealt away former All-Star reliever Clay Carroll and starter Clay Kirby, along with bench players Darrel Chaney, Merv Rettenmund, and Terry Crowley, and replaced them with veterans and talented players from the Reds’ minor league organization. Bob Bailey and Mike Lum, who had played a combined 21 full major league seasons, were acquired to reinforce the bench, while Howsam turned to a pair of hard-throwing home-grown pitchers Pat Zachry and Santo Alcala to supplement the pitching staff. With these changes, the Reds management believed that they had improved an already great club. “Our front line is the best eight men in either league,” Howsam declared, “and our bench is now as good as anybody has in baseball.”1

For now, the changing economics of the game did not affect the Reds. Within a year, the players’ newly won right to become free agents if they played a season without a signed contract would overturn baseball’s hidebound economic structure, but Howsam and the Reds dealt with it well during the 1975-1976 offseason. Despite an owners’ lockout during spring training, by Opening Day the Reds had signed all of their players except one, although they had to give some, like Joe Morgan and Pete Rose, significant raises to do so. Only the headstrong Don Gullett, the team’s best starting pitcher, was playing with an unsigned contract. Reds management, it seemed, was willing to adapt to the game’s new economic uncertainties. After all, as Morgan summarized, “The players realized it long ago. It’s a business.”2

Though they entered the 1976 season as the overwhelming choice to defend their division title and were 2-to-1 favorites to repeat as world champions, the Reds were just 12-10 on May 6 and still trailed the Los Angeles Dodgers by 2½ games on May 23. Only a few players struggled with injuries in 1976, notably Johnny Bench, whose “strange spasms of pain” compromised his production, but the rest of the team’s hitters compensated for their catcher’s relative decline. As for the pitchers, injuries pushed Gullett’s first start back to April 25, but, like the team’s hitters, its pitchers also picked up the slack. By the All-Star break, the Reds were 53-33 and in front of the second-place Dodgers by six games.3

And no one in the NL West really challenged the Reds during the second half of the season. The Dodgers managed to sneak to within seven games of Cincinnati in early September, but the Reds then won seven of eight games to widen the lead back to 11 games and finished the campaign ten games in front of the Dodgers. They were an excellent team. In fact, it is arguable that the 1976 Reds, despite a poorer overall record and a lesser margin of victory in their division, were the equal of Cincinnati’s more celebrated 1975 squad. Unlike the 1975 team, the 1976 group never slipped below .500, and while the 1975 Reds padded their gaudy won-loss record by beating the league’s worst teams, the 1976 squad won a remarkable 61.1 percent of the time against the best teams in the National League.4

The 1976 Reds burnished their reputation with remarkable play during the NLCS and in the World Series. With Gullett and Zachry on the mound, the Reds dominated the 101-win Philadelphia Phillies in the first two games of the best-of-five NLCS and then rallied for three runs in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game Three to complete the sweep and return to the World Series. There, the Reds dismantled the AL champion New York Yankees in all facets of the game, crushing them in a four-game sweep during an “utterly one-sided and almost passionless World Series.” Having won back-to-back titles and gone undefeated in the 1976 postseason, the Reds cemented their reputation as one of the better teams in baseball history. For Joe Morgan, the answer to the Reds place in history seemed obvious: “How can you have a much better team than this one?”5

But big changes were ahead for the Reds. For one, it was nearly certain that Gullett would opt to become a free agent and leave the team, which he did, less than a month later, by signing a six-year two-million dollar deal with the Yankees. Further, even as Howsam watched Tony Perez win Game Two of the World Series for the Reds with a ninth inning single off Catfish Hunter, he knew that the popular Cuban-born slugger would not be with the 1977 team. Faced with the dilemma of either turning first base over to Dan Driessen, one of the World Series batting heroes, or losing the young and promising player to free agency after the 1977 season, Howsam traded Perez and reliever Will McEnaney to the Montreal Expos for 37-year-old left-handed starter Woody Fryman, coming off a terrific bounce-back season, and hard-throwing 27-year-old reliever Dale Murray. In the years to come, as the Reds were unable to reach the heights they scaled in 1975 and 1976, Sparky Anderson, many of the team’s players, and even Howsam himself pointed to the loss of Perez’s clubhouse presence as the turning point in the team’s fortunes. And while that conclusion is debatable, it’s difficult to see how Howsam could have rationally opted to keep the 34-year-old Perez over the 26-year-old Driessen.6

Having won four of the last five NL West titles, including the two most recent campaigns by a combined 30 games over the second-place Dodgers, the Reds expected to continue their winning ways in 1977, even without Perez and Gullett. The Dodgers and their new manager, Tommy Lasorda, had other ideas. Under outgoing manager Walter Alston, the Dodgers had spent most of the first half of the 1970s as bridesmaids for the Reds, having finished in second place six times in the previous seven years. But Lasorda knew the Dodger squad well and they responded to his infectious positivism. “The players were ready, the pitchers were ready,” remembered veteran Dodgers pitcher Tommy John, “and we started off ’77 like a house afire. Boom.” Boom, indeed. Los Angeles leapt from the gate in 1977, winning 17 of its first 20 games and running-up a 13½-game lead on the Reds by May 27.7

Meanwhile, the Reds started slowly. So much so that at the end of May, the two-time defending champions were still a game under .500. Injuries slowed the team’s offense, while the Gullett-less rotation struggled so badly that one observer declared that there was “only one word for Reds’ hurlers – horrible.” The team offense stumbled too, failing to display the energy of previous seasons. It was obvious to all, including Sparky Anderson, that the Reds “weren’t the world champions [they] were supposed to be.”8

Still, the Reds were nothing if not resilient. They were tested, they were supremely confident, and they had little respect for the Dodgers’ staying power. “They just keep grinding it out,” noted a former teammate. So no one was terribly surprised when the Reds started gaining ground in early June. Facing “virtual elimination,” Cincinnati beat the Dodger aces, Don Sutton and Rick Rhoden, and then won 16 of 20 games to close to within 6½ games of the Dodgers on June 18. Bob Howsam, at least, believed that the Reds were poised to win the division again.9

So Howsam reconstituted the Reds in a flurry of moves at the June 15 trading deadline. First, he traded discontented ace reliever Rawly Eastwick and then dumped veteran pitchers Gary Nolan and Mike Caldwell while adding infielder Rick Auerbach. But those deals were all just a prelude to the biggest news of the trade deadline. Outbidding the Phillies, Howsam acquired ace starting pitcher Tom Seaver from the New York Mets for Zachry, slick infielder Doug Flynn, and two promising hitting prospects. Howsam realized that he had given up a lot for Seaver but was also aware that “you can’t give ashes for coal.” In making these deals, the Reds’ GM walked a difficult line between putting the best possible team on the field in 1977 and getting a return for players who, like Eastwick and Nolan, were determined to become free agents after the season.10

Seaver shut out the Expos in Montreal in his first start for the Reds, but that ultimately proved to be the team’s high-water mark. Six days later Seaver lost a 3-2 home contest to Tommy John and the Dodgers in what one close observer called the “biggest setback of the season.” And then things got much worse. Beginning on July 10, the Reds careened through a three-week losing skid that saw them drop 16 of 20 games, including eight games in a row, fall back under .500, and slip to 14 games behind Los Angeles. By the time Cincinnati rallied in late August to cut the Dodgers’ NL West lead to 8½ games, it was too little, and too late. The 1977 Reds won 88 games and even posted a winning record against the Dodgers, but still finished ten games behind Los Angeles.11

It was a team that prided itself on its group accomplishments but could only point to personal accolades in 1977. For example, Pete Rose and Johnny Bench each set records that year. No one, however, had a better year than George Foster. A “walking evangelist” who preached “brotherly love, clean living, and a love of God,” Foster wielded his ebony-stained bat (“The Black Death”) like an avenging angel that season, smiting NL pitchers with a .320 average, 52 home runs, and 149 runs batted in en route to the Most Valuable Player award.12

After finishing a season that left him feeling never “more disappointed in my life,” Bob Howsam turned over the general manager’s job to Dick Wagner, his longtime assistant and “hatchet man.” On principle, Wagner and the Reds eschewed free agency, the new way to accrue talent, and so turned to the trade market. He traded for sinkerballer Bill Bonham, purchased infielder Junior Kennedy, acquired speedy outfielder Dave Collins, and added relievers Doug Bair and Dave Tomlin. Then, for the second time in six months, the Reds shocked the game. Hoping to ensure that the Reds had the best pitching in baseball, Wagner dealt minor league first baseman Dave Revering and $1.75 million to the Oakland A’s for former Cy Young award winner Vida Blue, who was widely regarded as one of the better pitchers in the game. “People have said all we needed was pitching,” said Rose. “With Blue and Bill Bonham joining us, we got it now.”13

But just as they seemed to be back on top, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn dashed the Reds’ hopes by nullifying the Vida Blue trade on January 30, 1978. After a hearing that was “more like an inquisition than the fact-finding procedure,” Kuhn reaffirmed his earlier ruling that invalidated trades involving the exchange of more than $400,000. Reds president Howsam raged at Kuhn “kangaroo court” decision and Sparky Anderson declared, “If I hear [Kuhn] say just once more he’s doing something for the betterment of the baseball, I’m going to throw up.” Yet there was more than a touch of insincerity in Howsam’s position. After all, the Reds were one of a majority of owners that had urged Kuhn to cancel Oakland’s sales [of Blue, Joe Rudi, and Rollie Fingers] the previous year and Howsam had testified on Kuhn’s behalf in the subsequent court battle over the decision. It was evident to many at the time that Howsam’s fit was an illustration of the rule that the “only time an owner squeals is when his own ox is gored.”14

Another cloud also hung over the 1978 Reds. After an acrimonious negotiation with the team, Rose was playing on a two-year contract that allowed him to be a free agent after the season. Yet, if this was to be Rose’s last year with his hometown Reds, then he was determined to prove that he could still play. After becoming the player to accumulate 3,000 hits most quickly on May 5, Rose added to his lore in June and July. He was hitting just .267 on June 14, but grounded two singles into center field that day and then back in Cincinnati two days later, Rose doubled and singled in support of Tom Seaver’s only no-hitter. He had officially begun the longest hitting streak in NL history. By mid-July, Rose had hit in 30 consecutive games and was a national phenomenon. Good fortune allowed him to extend the streak on July 19, so that on July 25 he broke Tommy Holmes’ 23-year-old NL record and a week later tied Wee Willie Keeler’s 19th-century record by hitting in his 44th consecutive game. Just 12 games shy of Joe DiMaggio’s famed 56-game record, Rose’s streak ended the following evening when the Braves soft-tossers held him hitless.

The end of Rose’s streak began the Reds’ worst month of the 1978 season. Cincinnati had surged from the gate, winning seven of its first eight games, but the Dodgers and the surprising San Francisco Giants, their rotation augmented by a sanctioned trade for Vida Blue, remained in a dogfight with the Reds for most of the year. By August 1 Cincinnati trailed the front-running Giants by just a half-game, but they slumped through August and found themselves seven games behind the division-leading Dodgers by the beginning of September. For all intents and purposes, the Reds’ season was over. They righted the ship a bit in early September and finished the 1978 campaign just 2½ games behind Los Angeles, but that figure is highly misleading, since after the Dodgers clinched the division the Reds won their final six games while the Dodgers lost five of their last six meaningless contests. So the Reds were 20-8 down the stretch in 1978 but it was just “cosmetic improvement” and there was no pennant race in the final year of the Big Red Machine.15

November brought the final days of the Big Red Machine. After another protracted but this time fruitless contract negotiation with the Reds, Pete Rose filed for free agency after his record-setting 1978 season and signed with the powerhouse Phillies. Rose’s departure had been anticipated, if not expected, but the Reds’ firing of Sparky Anderson on November 28, 1978, shocked the baseball world. Rose’s stunned “What the hell’s going on?” was a typical reaction. While general manager Wagner had squabbled in the past with the fiercely loyal Anderson about the team’s coaching staff, he and Sparky were close friends and the general manager had given Anderson a resounding vote of confidence late in the season. “Sparky is in absolutely no jeopardy,” Wagner had said and then showed Anderson the article, proclaiming, “That is exactly the way I feel about you.” Further, Wagner had not suggested anything about a change during the rest of the season, nor on the Reds’ recently completed four-week tour of Japan. However, upon reflection Wagner decided that Sparky had not been stern enough at the helm, which led to the team’s not being “an aggressive ballclub in the field.” Believing that “the situation today calls for a new approach,” Wagner concluded that he couldn’t “just can’t sit back and let the ballclub go downhill.”16 Now, without Rose and Anderson, the Reds were the Big Red Machine only in metaphor.

However, the Reds did not fall apart after the departures of Rose and Anderson. Wagner’s Reds would eventually slide into irrelevance because of the team’s dogmatic refusal to partake in the modern economics of the game. Still, reinforced by a strong farm system, new manager John McNamara’s Reds performed quite well into the early 1980s. The Reds replaced Rose at third base with Ray Knight and put youngster Mike LaCoss into the rotation, but McNamara basically used the same squad that Anderson had fielded in 1978 and won the 1979 NL West title. After the Reds’ NLCS loss during a three-game sweep by the “We-Are-Family” Pirates, two more vital cogs of the Big Red Machine, Joe Morgan and Fred Norman, left the team as free agents. Scorning the free-agent market themselves, the Reds continued to fill holes from within, giving starting jobs to Dave Collins, Ron Oester, Mario Soto, Frank Pastore, and Joe Price. McNamara’s 1980 Reds started well, finished well and won 89 games, but ended the season in third place, 3½ games behind Morgan’s new team, the Houston Astros. Then Rose and the eventual world champion Phillies bested Morgan and the Astros during the NLCS in one of the baseball’s greatest playoff series. An aging Johnny Bench caught only seven games in 1981 and split time at first base with Dan Driessen during an injury-plagued season, but, powered by George Foster and Tom Seaver, the Reds played very well during both halves of the strike-ravaged campaign. In fact, the Reds compiled the best record in baseball that year, but missed the expanded postseason after finishing a half-game behind the Dodgers in the first part of the season and a game and a half behind the Astros during the season’s second act.

After the immense disappointments of 1981, Wagner dismantled the remnants of the old Big Red Machine by trading away Griffey and Foster. While Morgan, Rose, and Perez would play together again on the 1983 Phillies’ Wheeze Kids squad, only Bench, now playing an awkward third base to save his aching knees, and Dave Concepcion remained on the Reds. And both they and their Reds, who lost 101 games in 1982, cast but a faint shadow of the team’s faded glory.

ANTHONY GIACALONE is an independent historian specializing in 20th-century politics and popular culture. He has presented numerous research papers to SABR’s annual meetings and has contributed articles to Baseball Think Factory and The Hardball Times. He is currently writing a book on baseball in the 1960s and 1970s.

Notes

1 Other trades may have presented themselves under the right circumstances. As Mets star pitcher Tom Seaver haggled with management, rumors suggested that lefty Jerry Koosman might be on his way to the Reds. Doug Feldmann, The 1976 Cincinnati Reds (ebook) (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009), 21%, 30%.

2 Feldmann, The 1976 Cincinnati Reds (ebook), 28-30%.

3 Feldmann, The 1976 Cincinnati Reds (ebook), 34%, 29%, 40%.

4 The 1975 team posted a .744 winning percentage against the five worst teams in the league (teams with a composite .436 winning percentage) but just .561 against the five best teams in the NL (those with a combined .531 record). In contrast, the 1976 Reds were “only” .628 against the worst NL teams (combined .425) but were a phenomenal .611 against the league’s best teams (combined .557).

5 Roger Angell, Five Seasons: A Baseball Companion (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1977), 377. For discussions of the Reds’ “greatness” see Ray Fitzgerald, “These Reds don’t overwhelm you but baby, they’re tough,” Boston Globe, October 20, 1976, 69; Ulish Carter, ”Reds Great In Any Era, No Cinch Next Season,” New Pittsburgh Courier, October 30, 1976, 25; Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Reds Tinged With Greatness, Says Sparky,” The Sporting News, November 6, 1976, 3; Art Spander, “Yanks Mere Shell of Old Days,” The Sporting News, November 6, 1976, 14; Joe Falls, “Baseball’s Ten Best Teams,” The Sporting News, November 13, 1976, 13.

6 On Howsam having already decided to trade Perez, see http://reds.enquirer.com/bigred/bigred3.html. Nearly all the Reds echoed what Howsam said later, “Losing Tony took so much of the chemistry away. He had more of an effect on our team – on and off the field – than I ever realized.” Dan Epstein, Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America in the Swinging ‘70s (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2010), 210. There remains the question as to whether Howsam could have engineered a better deal for Perez. The Cleveland Indians needed a hard-hitting first baseman, were rumored to be interested in Perez and allegedly were willing to part with pitchers Pat Dobson, Jim Bibby, and/or young outfielder George Hendrick but the Reds balked when the Indians asked for hard-throwing reliever Jim Kern “and a prospect.” The Yankees too were interested in acquiring Perez, but felt that Howsam “wanted too much.” After Perez was traded to the Expos, the Yankees were “perplexed” because they felt they had offered the Reds more than they received from Montreal. Russell Schneider, “Indians Get Back Carty, Tribe’s ’76 Man of the Year,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1976, 50; Russell Schneider, “Indians Stronger on Mound, But Attack Looks Anemic,” The Sporting News, December 25, 1976, 44; Phil Pepe, “Yanks See Trade Shutout as Sign of Strength,” The Sporting News, December 25, 1976, 53; Phil Pepe, “Yanks Reward Cox’ Faithful Service,” The Sporting News, January 8, 1977, 35.

7 Earl Lawson, “Reds Confident of Success With Driessen and Fryman,” The Sporting News, March 5, 1977, 31; Earl Lawson, “Reds Blueprint Third Title, Admit It Won’t Be Easy,” The Sporting News, April 9, 1977, 22; Phil Pepe, Talkin’ Baseball: An Oral History of Baseball in the 1970s (New York: Ballantine Books, 1998), 274.

8 Earl Lawson, “Only One Word for Reds’ Hurlers – Horrible,” The Sporting News, July 16, 1977, 5; Earl Lawson, “Fast-Starting Morgan Shooting for Lofty 30-30,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1978, 10.

9 Most of the Reds, including Pete Rose, Gary Nolan, and Sparky Anderson, believed that the Reds were better than the Dodgers. Rose told Reds beat reporter Earl Lawson, “We’ve been out to L. A. and seen … that we’re a better ballclub than they are.” For Nolan, see Dick Miller, “Angels See Nolan, Brett Deals as Flag Coup,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977, 11. Well into midsummer Sparky Anderson believed that the Reds would “win our 95 games. If the Dodgers win 105, they’ll beat us. But they aren’t that good.” Dan Epstein, Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America in the Swinging ‘70s (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2010), 208. Earl Lawson, “Red Confidence Soars Again After a Visit to Dodger Den,” The Sporting News, June 18, 1977, 19; Bench quoted in “N. L. Flashes,” The Sporting News, June 18, 1977, 32. On the Reds’ lack of respect for the Dodgers and the feeling that L A would collapse in 1977: Sparky felt that the acquisition of Seaver would cause panic among the Dodgers. And even in August, Joe Morgan believed that the Dodgers might collapse: “The key to overtaking the Dodgers is pulling to within five games of them – and quick.” Then the Dodgers will hear footsteps “and those guys have rabbit ears.” See Earl Lawson, “Tom Terrific Caps Impossible Dream of Reds,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977, 16, and Earl Lawson, “Reds Weary, Resting on Fat Pay, Bench Thinks,” The Sporting News, September 3, 1977, 9. Further, the Reds just didn’t care much for many of the Dodgers and the feeling started at the top, as Sparky had publicly called Lasorda “Walking Eagle” because “he’s so full of it he can’t fly.” Epstein, Big Hair and Plastic Grass, 208.

10 Eastwick was originally supposed to go to the Mets instead of Zachry, but they refused to take him after Eastwick made it clear that he intended to enter the free agent re-entry draft at season’s end. Ray Kelly, “Bake Sale Leaves Some Sour Tastes in Philly,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977, 8; Randy Galloway, “Rangers Set for Twin Bills – Ellis No. 6 Starter,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977, 12. For Eastwick’s conflicts with the Reds, see Earl Lawson, “Tom Terrific Caps Impossible Dream of Reds,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977, 16. Seaver never forgave Mets owner M. Donald Grant. “Grant called me a Communist,” Seaver claimed later. “That was a plantation mentality that was going on there. Willie Stargell came over and he said, ‘They’re putting the big N on you. He’s putting the big nigger on you.’ Stargell was exactly right.” Phil Pepe, Talkin’ Baseball: An Oral History of Baseball in the 1970s (New York: Ballantine Books, 1998), 280. Ultimately, Seaver’s dispute with the Mets led to a series of trades even as far away as California, where Angels general manager Harry Dalton said of his team’s series of deadline trades, “Seaver caused this whole thing by being unhappy.” Dick Miller, “Angels See Nolan, Brett Deals as Flag Coup,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977, 11. Anderson’s reaction from Phil Pepe, Talkin’ Baseball: An Oral History of Baseball in the 1970s (New York: Ballantine Books, 1998), 377. Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977, 15.

11 The Sporting News Official Baseball Guide, 1978 (St. Louis: Sporting News Publishing Co., 1978), 151.

12 The prospect the Reds originally wanted instead of Foster was outfielder Bernie Williams, no relation to the Yankees all-star of the same name, who later hurt his arm and finished his career playing in Japan. Foster’s physique was so impressive that Joe Morgan believed only Willie Mays’ surpassed it and Pete Rose believed that Foster was “too strong to be playing baseball. He should be hunting bears with switches.” Earl Lawson, “Reds Relish Tom’s Humor as Well as His Hurling,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1977, 14. “I thought he might be a guy who batted .280 and hit 15 to 20 homers a season,” Morgan remembered of his first impressions of Foster, “But this …” Earl Lawson, “Foster Uses Long-Distance in Cincy for All It’s Worth,” The Sporting News, August 20, 1977, 12. Likewise, Foster’s close friend Willie McCovey admitted, “If I said that I thought he’d blossom into the star that he is today, I’d be lying.” Earl Lawson, “Foster’s Homers Stir Reds’ Disappointed Fans,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1977, 18; Earl Lawson, “Foster Promises He Won’t Be Confused Again,” The Sporting News, July 9, 1977, 5; Earl Lawson, “Foster’s ‘Black Death’ Pumps New Life Into Reds,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1978, 56.

13 Earl Lawson, “Reds Bench Warmers Face Up to Minor Spectre,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1978, 43; Earl Lawson, “Reds Map Out Short Relief Role for a Delighted Tomlin,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1978, 22. As in the Seaver trade, Wagner actually engineered a better trade than the one that was finalized. The Cubs had agreed to take Jack Billingham and Fryman for Bonham but Billingham vetoed the trade, saying, “I just don’t think that Wrigley Field is a fair park in which to pitch. So the Reds yielded future major-league closer Bill Caudill instead. ”Earl Lawson, “Reds Satisfy All Regulars; Bench Signs Five-Year Pact,” The Sporting News, November 26, 1977, 56; “Reds: ‘At Last We Have Pitching,” Hartford Courant, December 11, 1977, 3c; Earl Lawson, “Reds Bench Warmers Face Up to Minor Spectre,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1978, 43. There were other rumors as well that offseason, like the one, quickly denied by Howsam, that had the Reds moving Dave Revering, Billingham, and Cesar Geronimo to the Giants for John “The Count” Montefusco.” Sportswriters also speculated about the Reds trying to acquire the Brewers’ young shortstop Robin Yount and outfielder ?? for Davey Concepcion, which was denied by Milwaukee’s general manager Harry Dalton. Earl Lawson, “’No Way We’ll Trade Geronimo,’ Howsam Insists,” The Sporting News, October 22, 1977, 26; “Bunts and Boots,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1978, 56.

14 For example, the respected Jerome Holtzman related a “typical” story of two general managers who hoped for Kuhn’s removal. Kuhn’s talk of competitive balance was nonsense, said Holtzman, since it was the competition that assured the integrity of the game and nobody “should be allowed to rig the race” and establish himself as an “almighty seer.” Allegedly, the owners’ consortium urged Kuhn’s veto of Oakland’s 1976 sales so that the players were not made aware of their value on the open market. And then the owners misrepresented themselves in support of Kuhn’s legal defense of the decision because of the damages that each would incur if Finley proved successful. “Sure we didn’t tell the whole truth,” admitted one candid owner. “What were we supposed to do? If Kuhn loses, it would’ve cost each club about $170,000.” Jerome Holtzman, “Kuhn’s Legal Bills Irk Owners,” The Sporting News, March 4, 1978, 30. For the Reds’ reaction to the trade, see Earl Lawson, “Reds Infuriated Over Blue Decision,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1978, 46. Anderson quoted in “Insiders Say,” The Sporting News, March 4, 1978, 4.

15 Red Smith, “The End of Sparky’s Affair,” New York Times, November 29, 1978, B10.

16 Rose felt a bit betrayed by the way the Reds handled his contract. “This is the best place to play baseball,” he said. “I have business interests here. Because of that the Reds could offer me less.” But a few weeks later he had concluded, “It seems to me the way the Reds are negotiating this whole contract, they are saying between the lines, ‘We don’t want you no more.’ ” Dan Hafner, “Rose Says He’ll Go Out Swinging,” Los Angeles Times, October 1, 1978, C16; “Rose Says He’s Free Agent and 12 Clubs Can Draft Him,” Los Angeles Times, October 19, 1978, E4; “Miscellany: Rose tells Reds ‘no,’ Boston Globe, November 27, 1978, 32. For Anderson’s side of the firing, see Dick Young, “Sparky Was Hurt, Stunned When Ax Fell” Hartford Courant, November 30, 1978, 71A; Red Smith, “The End of Sparky’s Affair,” New York Times, November 29, 1978, B10; Los Angeles Times, November 29, 1978, E1.