Regular Season Showdowns

This article was written by Stew Thornley

This article was published in Spring 2018 Baseball Research Journal

One game for the pennant: winner takes the flag. Tiebreaker playoffs have produced drama—rookie Gene Bearden shutting down the Red Sox on one day’s rest in 1948 and Bobby Thomson hitting the most famous homer ever three years later—but these were the result of a tie at the end of the regularly scheduled season. A showdown game in the regular season has a strict definition, so strict that even the Minnesota at Boston game on the final day of the 1967 season doesn’t qualify; although the winner of that game (the Red Sox) got a direct trip to the World Series, it still wasn’t certain at the time. Only after Detroit was eliminated following the end of the Minnesota-Boston game was the pennant decided.

Few showdowns have been so serendipitous that the schedule brought the teams together at the end. Many pennants have been decided on the final game of the season, but rare has been the contest where either winner of the game went to the World Series or at least captured first place.

As great as the 1967 race was, 1908 produced two outstanding pennant races and the first two regular-season showdown games in the history of the major leagues.1 Special circumstances diluted these: Not all the games were played out in the American League, as was common at that time, and a replay of a tie game in the National League was tacked on at the end—not a tiebreaker game such as in 1948, but not one that was on the original schedule.

The number of regular-season showdowns are too plentiful to count on Mordecai Brown’s hand but not for Antonio Alfonseca.2

THE SHOWDOWNS

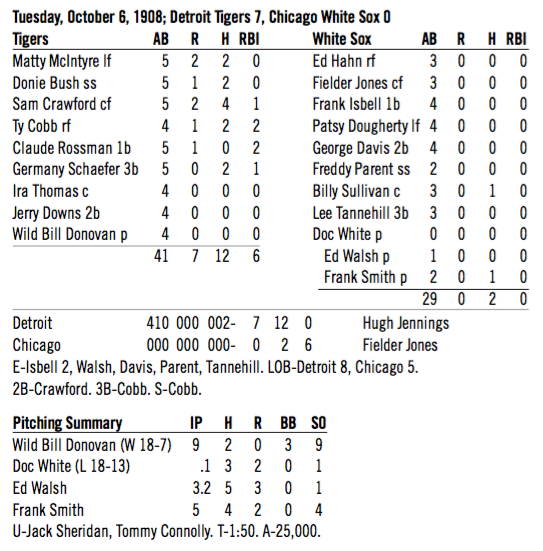

Tuesday, October 6, 1908—American League

Three teams were barreling to the end: Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit were close together into October and jockeying for position in the final week of the season. Cleveland was the first to stumble, splitting a doubleheader in St. Louis on Monday, October 5. Though they were only a half-game behind the leading Tigers and percentage points shy of the White Sox, even a win on Tuesday would leave the Naps short of the winner of the Detroit-Chicago game that day.

Three teams were barreling to the end: Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit were close together into October and jockeying for position in the final week of the season. Cleveland was the first to stumble, splitting a doubleheader in St. Louis on Monday, October 5. Though they were only a half-game behind the leading Tigers and percentage points shy of the White Sox, even a win on Tuesday would leave the Naps short of the winner of the Detroit-Chicago game that day.

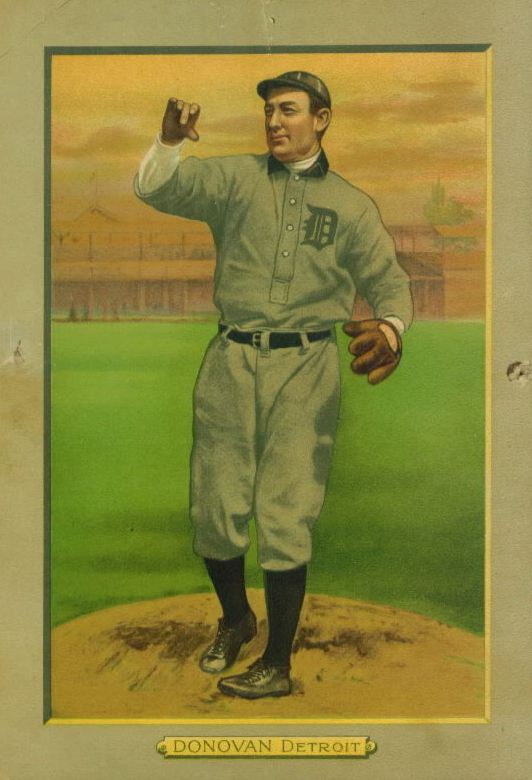

For the showdown in Chicago, Detroit had Bill Donovan on the mound. Frank Smith seemed the logical choice for the White Sox, but he was bypassed, possibly because of an ongoing feud with manager Fielder Jones. Known as the Piano Mover because of his furniture-moving prowess, the pitcher had acquired the name “Deserter” Smith for having left the White Sox during the season in a dispute with Jones and owner Charles Comiskey. “Apparently placing personal feelings ahead of other considerations, Jones chose Doc White to start, with just a day’s rest,” wrote David W. Anderson in More than Merkle.3

White lasted only four batters and was driven out after Ty Cobb drove in the first two runs of the game with a triple. Ed Walsh, who had pitched the day before, relieved, and the Tigers had two more runs by the time the top of the first was finished. Walsh allowed another run in pitching through the fourth. Smith finally got the call and went the rest of the way, giving up two runs in the ninth.

The game was effectively over before the White Sox even came to bat. Donovan scattered three walks and two singles in shutting out Chicago, 7–0.

In St. Louis, Cleveland beat the Browns, jumping the Naps past the White Sox into second place, but still a half-game behind Detroit. The disparity in number of games factored into the pennant finish. Detroit, with one decision short of the 154 scheduled, finished with a record of 90-63, ahead of the 90-64 Naps and 1½ ahead of Chicago.4

The Tigers left for home, awaiting a National League outcome that was even wilder than the one Detroit had just been involved in.

(Click image to enlarge.)

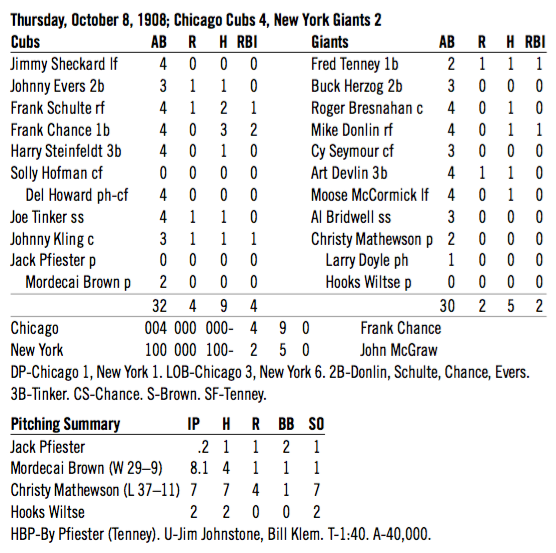

Thursday, October 8, 1908—National League

The National League also had a three-way race that season, involving New York, Pittsburgh, and Chicago. The showdown between the Giants and Cubs was loaded with controversy as the game was a makeup of a tie of possibly the most famous game ever played.

The National League also had a three-way race that season, involving New York, Pittsburgh, and Chicago. The showdown between the Giants and Cubs was loaded with controversy as the game was a makeup of a tie of possibly the most famous game ever played.

Merkle’s Boner on September 23 cost the Giants a win as Fred Merkle, with his failure to continue to second base on what appeared to be a game-ending single by Al Bridwell, was instead forced out, nullifying the run and ending the game at 1–1.

It wasn’t until the final week, as the Pirates were eliminated and the Giants had to stay alive with three wins over Boston, that the National League board of directors upheld the decision of umpire Hank O’Day to declare Merkle out in the September 23 game and the decision of league president Harry Pulliam to stand by the umpire.

When New York completed a three-game sweep over Boston on October 7, the Cubs were called back to the Polo Grounds—not a playoff but a replay of a tie game and a showdown to decide the pennant on Thursday, October 8.

Perhaps never before had there been such interest in seeing a baseball game. The gates were opened four hours before the first pitch and fans, some of whom had staked out spots in line the night before, poured in. Two hours before the scheduled game time, the Polo Grounds was full; fans, with or without tickets, were denied entry. Some tried scaling fences; others found high spots in the area that afforded even a partial view of the field. One fan, Henry McBride, had a spot on a pillar on the elevated station beyond center field. However, McBride got so excited when the Giants took a 1-0 lead in the last of the first that he lost his balance and fell to his death on cobblestones 25 feet below. His vacated spot was quickly filled.5

The Giants threatened to add to their lead, but Chicago’s Three-Fingered Brown relieved starter Jack Pfiester, quelled the rally, and held them without another run until the seventh. Meanwhile, the Cubs roughed up New York ace Christy Mathewson for four runs and held on for a 4-2 win and the National League pennant. The Cubs went on to win the World Series for the second straight year, their last world title for more than 100 years.

(Click image to enlarge.)

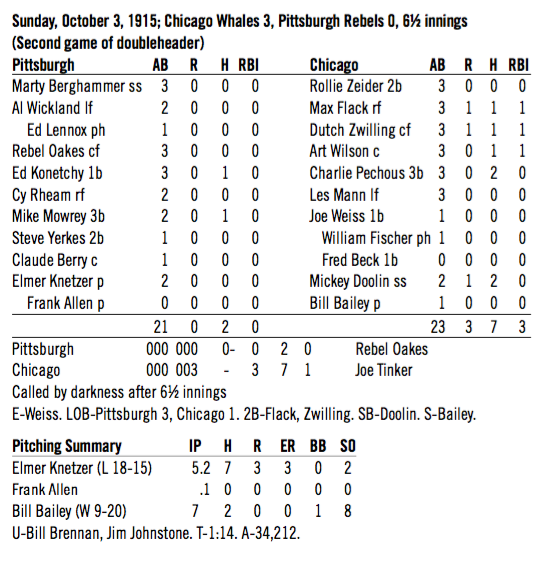

Sunday, October 3, 1915—Federal League

As was the case in the American League in 1908, a showdown game in the Federal League came down to an uneven situation because of games that weren’t made up. And one that was made up created a controversy of its own.

As was the case in the American League in 1908, a showdown game in the Federal League came down to an uneven situation because of games that weren’t made up. And one that was made up created a controversy of its own.

The final games of the 1915 season involved a three-way race between the St. Louis Terriers, Chicago Whales, and Pittsburgh Rebels.

The Whales closed their season against the Rebels, first in Pittsburgh and then in Chicago. On Friday, October 1, the game in Pittsburgh was rained out, leaving the Rebels in first place by a half-game game over St. Louis and 1½ games over Chicago.

Federal League president James Gilmore, a Chicago native and friend of Whales owner Charles Weeghman, ordered that the rainout in Pittsburgh would have to be made up as part of a Sunday doubleheader in Chicago. Dan Levitt, author of The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy, said it was Charles Weeghman who suggested the make-up game in Chicago. “Pittsburgh naturally opposed this proposition,” Levitt wrote, “but Gilmore sided with his Chicago pal. He ruled that if Pittsburgh did not play a doubleheader, he would rule both games forfeit.”6

On top of that, in Pittsburgh, the Whales then swept a Saturday doubleheader from the Rebels to move a half-game in front of them. St. Louis lost to Kansas City and also was a half-game out but was percentage points behind Pittsburgh. The Terriers, with one game scheduled on the final day, were out of the race; they could pass either the Whales or the Rebels—but not both.

The Whales and Rebels headed for Chicago for a doubleheader on the final day of the season on Sunday, October 3. In the first game, Chicago carried a 4–1 lead into the ninth but a misplayed fly ball allowed the Rebels to tie the game and then win in the 11th inning.

The pennant came down to the second game, which started at 4:11 p.m. and almost assuredly would be an abbreviated game. Umpire Bill Brennan asked the time of sundown, which was 5:24, and said he would stop the game at that time.7

The game was scoreless until the bottom of the sixth when Max Flack’s two-out double scored Mike Doolin from third. The Whales scored two more for a 3–0 lead and then put down the Rebels in the top of the seventh. The time was 5:25, and Brennan announced the game over.

The Rebels, dropped to third place, a half-game behind Chicago and St. Louis. The win put the Whales, at 86-66, a fraction of a percentage point ahead of the 87-67 Terriers. (The margin was .0008544.) Had outfielders Rebel Oakes and Cy Rheam been able to track down Flack’s drive, as they almost did, the game likely would have ended in a tie, which would have left as the Pittsburgh in first place, percentage points in front of St. Louis.

Instead, darkness ended the Pittsburgh chances and the history of the Federal League, which did not return in 1916.

Whales president Charles Weeghman hadn’t had enough as he sought to get into the city series with the Cubs and White Sox, and then challenged the Boston Red Sox and Philadelphia Phillies to play the winner of their World Series. The Chicago Tribune reported, “After this Mr. Weeghman will just sit back and claim the world title by default, for there isn’t a chance of his cutting in on the big show and the big coin.”8

(Click image to enlarge.)

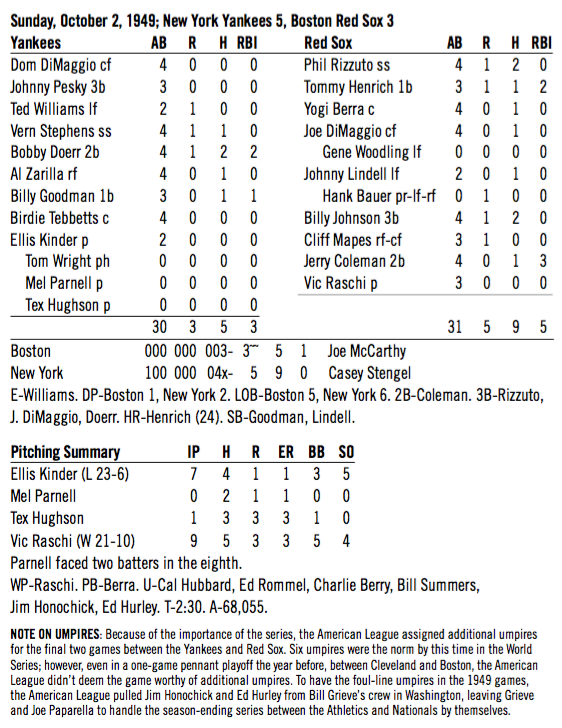

Sunday, October 2, 1949—American League

The Boston Red Sox came to New York for a season-ending weekend series holding a one-game lead over the Yankees. In the Saturday game Joe DiMaggio—returning after a two-week absence because of pneumonia9—sparked a comeback with hits in consecutive innings, and Johnny Lindell broke a 4–4 tie with an eighth-inning home run to create a showdown game on Sunday.

The Boston Red Sox came to New York for a season-ending weekend series holding a one-game lead over the Yankees. In the Saturday game Joe DiMaggio—returning after a two-week absence because of pneumonia9—sparked a comeback with hits in consecutive innings, and Johnny Lindell broke a 4–4 tie with an eighth-inning home run to create a showdown game on Sunday.

In the finale, Ellis Kinder—looking for his 14th straight win and 24th of the season—pitched for Boston and gave up only a first-inning run over seven innings, despite a late night, according to David Halberstam in Summer of ’49.10 That run—on a lead-off triple by Phil Rizzuto and a run-scoring ground out by Tommy Henrich— held up as New York’s Vic Raschi kept the Red Sox from crossing the plate.

With Boston down 1–0 in the eighth, manager Joe McCarthy sent Tom Wright up to hit for Kinder and then had Mel Parnell relieve in the bottom of the inning. Parnell, who had started the Saturday game, gave up a lead-off homer to Henrich, and the Yankees added three more to carry a 5–0 lead into the ninth. Kinder was furious about being lifted and on the train back to Boston, “apparently quite drunk, [he] sharply criticized his manager,” according to Mark Armour in his biographical sketch of Kinder.11

The Red Sox had two on with one out in the ninth when Bobby Doerr drove a triple beyond DiMaggio in center. DiMaggio, recognizing that he was hurting the Yankees by playing in his weakened condition, called time and took himself out of the game. The fans, recognizing why he was doing this, gave DiMaggio an ovation as he ran off the field.12

One out later, Billy Goodman singled home Doerr, but Birdie Tebbetts fouled out to end the game and send the Yankees to the World Series, the first of five straight they would win.

(Click image to enlarge.)

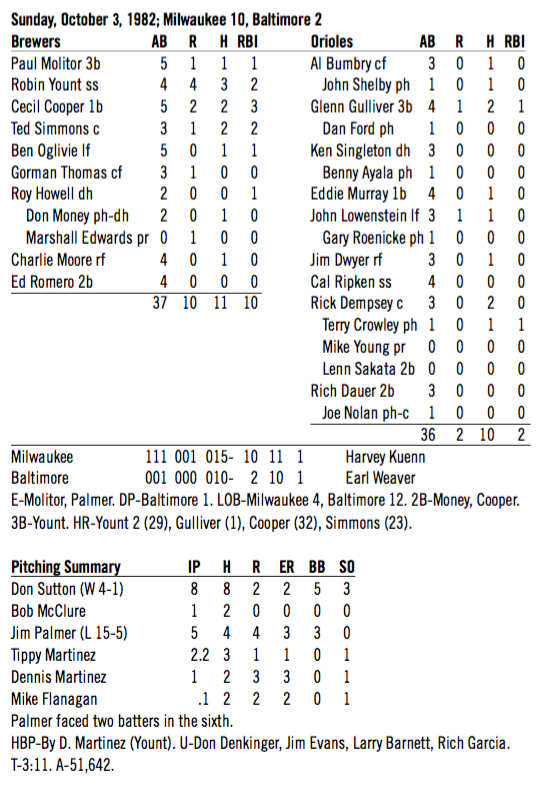

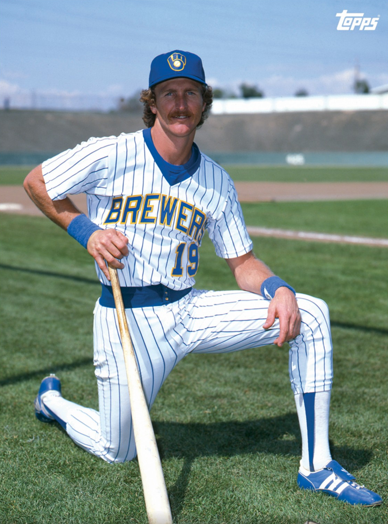

Sunday, October 3, 1982—American League East Division

Earl Weaver’s final season as manager of the Baltimore Orioles didn’t figure to be a championship year.13 On August 22 the Orioles were in third place, 7½ games behind the East-Division-leading Milwaukee Brewers.

Earl Weaver’s final season as manager of the Baltimore Orioles didn’t figure to be a championship year.13 On August 22 the Orioles were in third place, 7½ games behind the East-Division-leading Milwaukee Brewers.

A hot month, however, brought the Orioles to within three games of the Brewers as Milwaukee came in for a season-ending four-game series. Baltimore’s doubleheader sweep on Friday and an 11–3 win on Saturday deadlocked the teams for first place with the deciding game on Sunday, October 3.

The starters were future Hall of Famers—Don Sutton for Milwaukee and Jim Palmer for Baltimore. Another Cooperstown-bound star quickly put the Brewers ahead to stay. Robin Yount, the second batter of the game, homered. Yount, who would be voted the American League Most Valuable Player for that season, homered again in the third, and the Brewers had a 3–0 lead.

Sutton pitched eight strong innings, and Milwaukee had a 5–2 lead going into the ninth when they padded the margin with five more runs for a 10–2 win. As the Brewers celebrated their trip to the playoffs and eventually the World Series, fans at Memorial Stadium cheered for Weaver, who came to the top of the dugout steps and waved to the crowd.

(Click image to enlarge.)

SINCE THEN …

The Brewers-Orioles game was the last showdown game during the period that only first-place teams could advance toward the championship. In 1994 Leagues were divided into three divisions, with each champion plus a wild-card team moving on.

Two showdown games in a battle for first place have occurred since then:

- September 29, 1996: The San Diego Padres beat the Los Angeles Dodgers 2–0 in 11 innings.

- October 3, 2012: The Oakland A’s beat the Texas Rangers 12-5.

However, in both cases the loser made the playoffs as the wild-card team. No showdown games have been played for a wild-card spot. Never again will we have a 1908 or 1949 finish, with the winning team heading directly to the World Series. Any meaningful showdown games will have to be among teams that do not have the top records in the league. Baseball changes. We may miss what’s gone but at least we can revel in its history.

STEW THORNLEY has been a SABR member since 1979. He is an official scorer for Major League Baseball and a member of the MLB Official Scoring Advisory Committee. He has visited the graves of nearly every member of the Baseball Hall of Fame. He once attended the funeral of a complete stranger just to get a free lunch. His interest in showdown games goes back to his experience as bat boy with the Minnesota Gophers, who beat Steve Garvey’s Michigan State team in a showdown game in 1968.

Notes

1 The recognized major leagues are the National Association (although that is often disputed but irrelevant since no showdown games occurred), National League, American Association, Players’ League, American League, and Federal League. The author recognizes that various Negro Leagues should be considered major, as well, although the difficulty of determining any showdown games in these leagues has caused him to look at only white or integrated leagues.

2 In case an explanation is needed, Mordecai Brown had three fingers on his right hand (hence the nickname “Three-Fingered”), and Antonio Alfonseca has six fingers on each hand.

3 David W. Anderson, More than Merkle: A History of the Best and Most Exciting Baseball Season in Human History (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 189.

4 In More than Merkle (page xix), David Anderson wrote, “Cleveland finished a half game behind the Tigers behind the Tigers because of a quirk of the weather and in the rules. League officials ruled that the Naps had finished their season and Detroit was not obligated to play a game that had been rained out. As a result of this outcome, in later years teams in contention were required to play any game that had a bearing on the pennant race.”

5 Stew Thornley, Land of the Giants: New York’s Polo Grounds (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000), 58-60. Other sources: “Giants Bow to Bitter Defeat” New-York Tribune, October 9, 1908, 1; “As Seen From Coogan’s Bluff: Thousands Watch Corner of Playing Field and Enjoy Baseball Atmosphere,” New-York Tribune, October 9, 1908, 5; “Forty Thousand See Giants’ Hope for Pennant Die,” The World, October 9, 1908, 1; “Jam at the Gates: Spectator Killed,” The World, October 9, 1908, 2; “The Cubs Win the Pennant,” New York Times, October 9, 1908, 2; W.J. Lampton, “Up on Coogan’s Bluff: Four Hours with the Unseeing but Anxiously Listening Thousands” and “How Joy’s Mirage Turned to Gloom,” New York Times, October 9, 1908, 2.

6 Daniel R Levitt, The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy (Lanham, Maryland: Ivan R. Dee, 2012), 219.

7 “Whales Win Pennant as 34,000 Fans Cheer” by J.J. Alcock, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 4, 2017, 13.

8 “Weeghman to Challenge for the World’s Title,” Chicago Tribune, October 4, 2017, 13.

9 DiMaggio had missed the first part of the season with lingering problems with bone spurs, and his late-season absence was attributed to pneumonia by Lawrence Baldassaro in his article on DiMaggio for the SABR BioProject (https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/a48f1830) and by Halberstam in Summer of ’49 (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1989.) An article, “Gloom Pervades Yankee Quarters But Stengel Looks for Triumph,” on page 16 of the October 1, 1949, New York Times said DiMaggio was “recovering from a virus infection that felled him Sept. 18.”

10 Halberstam, 44. Halberstam cited Kinder’s roommate, Joe Dobson, that Kinder got to his room at 4 a.m., “quite drunk, with a lady friend Dobson had never seen before.”

11 Mark Armour, “Ellis Kinder,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/4838dc23.

12 John Drebinger, “Yanks Whip Red Sox in Season Finale to Win 16th American League Pennant,” New York Times, October 3, 1949, 21.

13 Weaver, of course, returned and managed Baltimore in 1986 and 1987, but he announced his retirement in 1982 and stepped aside for Joe Altobelli, who led the Orioles to the world championship the following year.