Researching Ted Williams’ Latino Roots

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

This article was published in The National Pastime: Pacific Ghosts (San Diego, 2019)

There was one sentence that I read in Ted Williams’ autobiography, My Turn At Bat, which set me off on a personal research journey that took me some unexpected places and raised a few eyebrows along the way. It was a 44-word sentence about his mother, which I really only focused on the third time I read the book:

There was one sentence that I read in Ted Williams’ autobiography, My Turn At Bat, which set me off on a personal research journey that took me some unexpected places and raised a few eyebrows along the way. It was a 44-word sentence about his mother, which I really only focused on the third time I read the book:

“Her maiden name was Venzer, she was part Mexican and part French, and that’s fate for you; if I had had my mother’s name, there is no doubt I would have run into problems in those days, the prejudices people had in Southern California.”1

I was re-reading his autobiography while trying to organize material for the 1997 Masters Press book that I co-authored with Jim Prime: Ted Williams, A Tribute. I hadn’t read My Turn At Bat for maybe 10 or 15 years, but the sentence probably caught my eye that time around because early in the 1990s I had married a woman of Mexican-American ancestry. I wanted to find out more about May Williams’ family background, but her surname was misspelled in Ted’s book (Venzer for Venzor) which stymied further research.

After Jim and my book came out, we heard from one of Ted’s nephews, Manuel Herrera. He was a treasure trove of family lore and put me in touch with Sarah Diaz of Santa Barbara. She was May’s sister — Ted’s aunt. She was 94 years old at the time, but very sharp. Talking with both Manny and Aunt Sarah, I was able to put together a kind of family tree. Both of Ted Williams’ maternal grandparents had come to the United States from Valle de Allende, Chihuahua, Mexico. Pablo Venzor and Natalia Hernandez Venzor entered the US at El Paso around 1890. May Venzor was born in El Paso in 1891. The family ultimately made its way to Santa Barbara.

May met her future husband, Sam Williams, in the Salvation Army. They made their home in San Diego.

One of May’s brothers, Saul Venzor, was an accomplished baseball pitcher in Santa Barbara. When I learned the names of Ted’s uncles and aunts, I dug into more research. In Saul Venzor’s case, his 1963 obituary in the Santa Barbara News-Press said that he had given Ted Williams’ his first baseball lessons and that Ted had told friends that “Mr. Venzor was his first instructor.”2

While I was accumulating more information about Ted’s family background — on both sides of the family — I had the opportunity to have lunch with Ted at his Florida home in April 2000. I asked him about Uncle Saul. He said, “He was my mother’s brother…He was a pretty good baseball player. Santa Barbara. I don’t know any other relatives that had much ability.”3

And then he changed the subject. It didn’t feel awkward, but it was clearly something he preferred not to talk about. As Ted himself had written in My Turn at Bat of growing up in San Diego in the 1930s, he was well aware of the racial prejudice he would have faced, with “no doubt” about it.4 As Al Cassidy, the executor of Ted Williams’ estate, told writer Ben Bradlee about Ted’s early days, “Ted didn’t want anyone to know he was part Mexican. It concerned him. He was afraid they wouldn’t let him play. He’d say, ‘It was an entirely different time back then.’”5

Three of Ted Williams’s uncles with his grandmother Natalia Hernandez in Santa Barbara, circa 1954. From left: Pete Venzor, Saul Venzor, Natalia Hernandez, Paul Venzor. (MAY WILLIAMS COLLECTION)

Over time, I visited San Diego, Santa Barbara, and Ted’s uncle Ernesto Ponce in El Paso. I kept gathering information and then wrote an article for the Boston Globe Magazine. The article was published on June 2, 2002. That Ted Williams could be considered Hispanic came as a total surprise to those who never guessed the “Williams” surname might have masked another element of his ethnicity. It was the first time the story had been explained.6

After his death, I helped organize three celebrations of Ted Williams’ life during 2002–03, first at the Boston Public Library, then at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, and lastly (working with the local SABR chapter) at the San Diego Hall of Champions. I had met Sam and John Theodore “Ted” Williams (sons of the Hall of Famer’s brother Danny) during a memorial event at Fenway Park in 2002. I invited the many relatives I had called or visited, and 33 relatives from Ted Williams’ extended family attended the celebration at San Diego’s Balboa Park at the Hall of Champions. Their surnames exemplified their own Latino background — names such as Amidon, Contreras, Mata, Ortiz, Ronquillo, and Venzor. There’s a photograph of them all, which first ran in The Kid: Ted Williams in San Diego (Rounder Books, 2005) a joint project of nine SABR authors.7

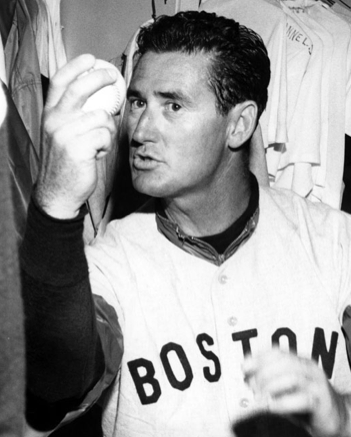

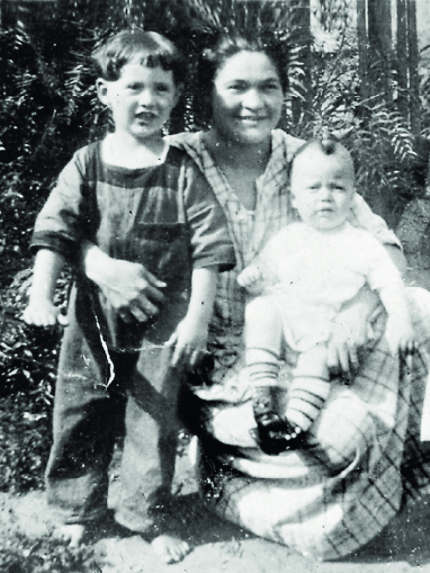

Ted Williams, left, poses with his mother May and brother Danny, circa 1921. (MAY WILLIAMS COLLECTION)

In July 2010, nephew Ted Williams and I both took a trip to Mexico. Ricardo Urquidi Espinoza had invited me to come to speak at two different events: an evening gathering of sportswriters in the city of Chihuahua itself and then at a “Conferencia Historica” on the Patio Central de la Presidencia Municipal on July 10, 2010, in the city of Hidalgo del Parral. I invited Ted along. We also took in a baseball game in Parral, and made a side trip to the village of Valle de Allende. We met with local genealogists and historians there, and a couple of Venzors, too. My further research was eventually gathered into the book Ted Williams: First Latino in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

The book provokes debate over whether Ted Williams can be considered Latino, given that he apparently lived and identified as Anglo. Scholar Adrian Burgos Jr. argues that it is “important that we do not rewrite the history of Latinos and baseball by retroactively inserting Williams.” Burgos writes that Ted Williams should not be considered as Latino because he “did not identify as Latino nor was he racialized as such during his legendary career.”8 This seems to be the stance of Major League Baseball as well, who left Ted off a ballot of 60 “Latino Legends” in 2005.9 Nonetheless, Ted Williams’ previously unsung background has subsequently been incorporated into scholarship about him. (Ben Bradlee Jr. even mentioned my work in his 856-page tome, The Kid. He wrote, “No reporter…dug into [Ted Williams’] Mexican heritage until Bill Nowlin explored some of the Venzor family lineage in an article for the Boston Globe Magazine.”10) Although Ted might have habitually brushed the subject of his heritage aside, researchers no longer can.

BILL NOWLIN has written seven books about Ted Williams, the most recent being “Ted Williams: First Latino in the Baseball Hall of Fame.” His eighth, “Ted & Jimmy,” will be about Ted Williams’s work in raising money to fight cancer in children. He is a long-serving member of SABR’s Board of Directors.

Members of Ted Williams’s extended family in Balboa Park, where they gathered in 2003 during the celebration of his life at the San Diego Hall of Champions. Pictured from left: Peggy Amidon, Judi (Amidon) Vista, Linda Amidon (Jim’s wife), Louie Mata, Louie Mata III, Mari Mata, Mitchell Amidon (Jim’s son), Virginia Amidon, Jackie Mata, Bill Amidon, Suzy Amidon, James Amidon, Ron Amidon, Nicholas Atondo, David C. Allen, Frank Venzor, Alyse Amidon, Dee (Venzor) Allen, Gero Lucero, Erich Venzor, Hugo Nathan Gaytan, Gudrun Venzor, David Ronquillo, Chaz Venzor, Ted Williams, Rose (Venzor) Larson, Karma Barber Arnold, Bob Larson, Teresa (Cordero) Contreras, Carrie (Venzor) Ortiz, unknown, Carol Jean Contreras. (COURTESY OF BILL NOWLIN)

Notes

1 Ted Williams with John Underwood, My Turn at Bat (New York: Fireside, 1966, 1988), 28.

2 Santa Barbara News-Press, August 16, 1963.

3 Author interview with Ted Williams on April 28, 2000.

4 My Turn at Bat, 28.

5 Ben Bradlee Jr. interview with Al Cassidy, December 5, 2002. See Ben Bradlee, Jr., The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013), 6.

6 Bill Nowlin, “El Splinter Esplendido, Ted Williams’s Latino Heritage,” Boston Globe Magazine, June 2, 2002.

7 The Kid: Ted Williams in San Diego, ed. Bill Nowlin (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2005). Contributing SABR authors were Carlos Bauer, Dan Boyle, Tom Larwin, Joe Naiman, Bill Swank, James D. Smith III, Stew Thornley, and G. Jay Walker.

8 Adrian Burgos, Jr., “No, Ted Williams Was Not Baseball’s First Latino Superstar,” The Sporting News, June 24, 2015.

9 Richard Sandomir, “Who’s a Latino Baseball Legend?” The New York Times, August 26, 2005. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/26/sports/baseball/whos-a-latino-baseball-legend.html

10 Ben Bradlee, Jr., The Kid, 27, 28.