Jackie Robinson: Comic Book Superhero

This article was written by Tom Hawthorn

This article was published in Not an Easy Tale to Tell: Jackie Robinson on the Page, Stage, and Screen (2022)

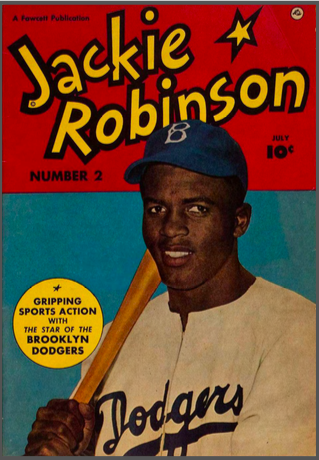

The cover of the second issue of the Fawcett Publication of Jackie Robinson.

A new publication appeared on magazine racks as the first game of the 1949 World Series neared. It had a bright yellow cover with garish red letters at a jaunty angle spelling out Jackie Robinson’s name with a subdued subheading declaring him to be a “BASEBALL HERO.” A colorized photo of the smiling player in a blue Brooklyn Dodgers cap was the dominant image, while the secondary art included a black-and-white photograph of Robinson after taking a practice swing. “True life story of the famous Brooklyn Dodger,” read a tagline. The price was 10 cents.

The 36-page issue offered the player’s biography in comic-book fashion, mixing the personal with the anecdotal, as well as statistics from his first two-and-a-half seasons in the National League. The book concludes with Robinson’s selection to the 1949 All-Star Game, though does not mention his batting championship or Most Valuable Player award at the end of the season. The comic was likely rushed to the printing press before the season ended and the World Series got underway.

The comic book’s tone is set in the first panel, which occupies two-thirds of a page. Robinson, “Marvel of the Baseball Diamond,” is described as “the sharpest hitter, the speediest baserunner and the surest fielder in our national pastime!” The player “rose to fame the hard way, as he is also the first Negro in organized baseball. Hailed today as a new Ty Cobb, brilliant Jackie has overcome all handicaps to become a symbol of the fighting spirit of the American boy!”1

The story then follows a predictable biographical trajectory: birth in Cairo, Georgia followed by a move to Pasadena, California, where his single mother encourages his studies, while discouraging an obsession with baseball. The industrious boy sells newspapers on the street corner and hustles change as a bootblack. One day, Tony Lazzeri stops by for a shoeshine. Jackie asks if he is “the fellow who hit all those home runs in the Coast League last year,” which places the fictional encounter in 1926, the year after Lazzeri hit 60 homers with the Salt Lake City Bees. Lazzeri helps young Jackie get a job at the baseball park.

Robinson’s athletic exploits in football, basketball and track at Muir Technical High School, Pasadena Junior College, and the University of California, Los Angeles are described. He meets nursing student Rachel Isum at university, enlists in the U.S. Army following Pearl Harbor before being commissioned as a 2d lieutenant, and then plays for the barnstorming Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues after the war.

He is scouted by Clyde Sukeforth of the Dodgers and signed by Branch Rickey, “maker of champions,” who encourages the player to marry Isum. “The world was electrified with the news of Jackie’s signing by the Dodgers,” the book states. “Millions hailed Branch Rickey’s courageous act—a few condemned him for breaking the Jim Crow code!”

The code is not explained in the comic, though a later panel includes a handwritten letter reading, “If you try to play ball down here, we’ll ride you out of town. [signed] K.K.K.” Another panel includes gentlemen with Southern accents condemning his hiring. The player later dutifully leaves the field at spring training in Florida when a sheriff in a cowboy hat puts a hand on his shoulder to say, “You git off’n this heah field right now! Our law says cullahd and white cain’t play together!”

Later, the player endures taunts by opponents, including a rival player who holds aloft a black cat with the taunt, “Here’s one of your relatives.” The Phillies target Robinson with expletives shouted from the dugout (rendered in typographical symbols—@*#%$—known as grawlixes) and a threatened strike by St. Louis Cardinals players.

A Dodgers exhibition tour of the South leads to a panel showing hooded Klansmen threatening to tar and feather Robinson and Black teammate Roy Campanella. Robinson’s response is to deliberately strike a sitting Klansman sitting in the stands in civilian clothes with a foul ball.

The flavor of the hagiography is captured in the closing two sentences.

“He is loved by every fan in America for his courage, tact and brilliance, on the field and off,” the comic book stated. “Long may Jackie Robinson, first Negro in Big League Baseball, star in his country’s great national game!”

While the story does not avoid the racism faced by Robinson and the other early players who integrated major-league teams, it is a word that does not appear in the comic book. While the book acknowledges the limited career possibilities of a young Jackie Robinson—elevator operator or athlete—it does not address the unfairness of segregation.

Cathy Keen, an archivist with the National Museum of American History, reviewed the portrayal of Robinson as a comic-book hero in a 2013 article in which she found “the abuses he endured are addressed in a vague, sanitized way. Why were the sharp edges of reality so blunted in this comic book? There are many possible reasons—protecting children who idolize the players, avoiding offense, wishful thinking—but perhaps one was to focus on the game.”2

The comic certainly does not spare in idolizing Robinson’s skill as a hitter, fielder, and, especially, baserunner. The message from Robinson to his youthful readers is one of promoting good citizenship. The inside front cover included a signed letter from the player urging children to join an organized baseball team. “Keep yourself in fine physical trim,” Robinson urged. “Don’t smoke and don’t touch alcoholic liquors.”

The inside back cover included an autographed, full-page photograph of the player after taking a practice hack. The back cover got into the nitty-gritty of selling mail-order merchandise with an image of the player with a message balloon reading, “C’mon, kids! These items are a hit with all my fans!” The player is depicted wearing a Jackie Robinson cap ($1) and a Jackie Robinson T-shirt ($1). Cotton sweatshirts were also available for $1.75, while a 27½-inch girl’s scarf cost $1. The mailing address for orders was in Woodmere, a hamlet on Long Island, about 16 miles east of Ebbets Field in Brooklyn.

While there was limited news coverage of the release of the comic book, its origins can be traced to Robinson’s desire to make an income in the offseason. He had led Jackie Robinson’s All-Stars, a barnstorming team, but there was a financial risk in backing a traveling team, while being on the road kept him even longer from his wife and son, who was born five months before his father made his major-league debut.

In 1949, Robinson was hired as a floor salesman by Sunset Appliance Stores, a company with a storefront in Queens about to open a second location in Times Square. Robinson’s first day on the job came at the new store on the evening of October 8, when he was assigned to greet admirers and well-wishers. Incredibly, he had gone 1-for-3 with a run scored and a run batted-in that afternoon as the Dodgers lost Game Four of the World Series to the New York Yankees by 6-4. (The second baseman also helped complete an oddball, 5-2-4 double play in the first inning.) The afternoon following his debut at the appliance store, Robinson was once again on the field at Ebbets Field, going 1-for-3 with a single and an RBI sacrifice fly as the Yankees won the championship with a convincing 10-6 victory.

Robinson’s offseason professional life changed with a visit to the penthouse offices of Kagran Corp. at W. 58th St. and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan’s Theatre District. He met with company president Martin Stone, a lawyer four years older than the ball player. Stone had clerked for U. S. Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo and had served as an unofficial adviser to President Harry Truman, yet he would find success in broadcasting as an agent, producer, and licensor.

Stone and a friend had started a radio program called Author Meets the Critics on a station in Albany, New York. The concept, though highbrow, was simple. Two reviewers would evaluate a bestseller before being joined by the author for unscripted conversation. After serving in the Navy during the war, Stone decided to go into show business as an entertainment lawyer. He brought his radio program to television, the growing media he correctly figured was soon to dominate the landscape.

Stone was agent for Bob Smith, the host of a children’s radio program on WEAF in New York. Smith’s trademark greeting was a bumpkin’s hearty, “Oh, ho, ho, howdy doody.” Stone wanted him to bring the program to television. Puppet Playhouse debuted on WNBT, part of the NBC network, just after Christmas in 1947. A year later, the renamed Howdy Doody Show was a marketing juggernaut, as some 95 products, with many more to come, had been officially licensed.

The actor Gabby Hayes, known as a sidekick in B-movie westerns, appeared on Howdy Doody and joined Stone’s stable. One of the first of his many licensing deals was to lend his name to a regular comic book issued by Fawcett Publications. The ball player arrived in Stone’s penthouse office at an opportune time. The lawyer’s recent experience placed him in a position to exploit a lucrative marketing campaign aimed at children and adults.

“For five months, I worked at untangling a lot of Jackie’s previous contracts—he’s entirely too trusting a guy,” Stone later told Tex McCrary and Jinx Falkenburg, a popular husband-wife team who hosted radio and television programs, as well as writing a column for the New York Herald-Tribune. “Then we brought out a book on his life, and negotiated a movie based on his life. Once the ball was rolling, we broke with full-page ads of Jackie Robinson dolls, T-shirts, comic books, etc.—about thirty franchises. Then I turned to WNBC again and worked out a Saturday morning radio show with Jackie. He’s pretty happy about the whole thing—this way he has a chance to see his wife and boy during the offseason.

“The best proof, I guess, of the success of the merchandising of Jackie’s name came when another ballplayer came in here and said, ‘Hello, Marty, I’m Pee Wee Reese. Is there anything you can do with me?’”3

Stone’s merchandising and licensing operations expanded to include such athletes as figure skater Sonja Henie, as well as the comedian Jackie Gleason and the television show Lassie. By the end of the 1950s, Stone estimated he had arranged about $500 million in licensing agreements.

He continued to serve as Robinson’s attorney for the player’s lifetime, notably arranging his hiring as an executive by the Chock full o’ Nuts chain of coffee shops and sudden retirement from baseball. The decision was revealed in a Look magazine article, the news of which leaked on January 7, 1957, an exclusive for which the publication paid $50,000, more than any salary the athlete had ever made in a season. The Stone and Robinson families remained close for more than two decades, and Rachel Robinson attended Stone’s funeral when he died in 1998, aged 83.

At the heart of the marketing campaign devised by Stone for his baseball client was the production of The Jackie Robinson Story, a Hollywood biopic written by Lawrence Taylor and Arthur Mann, the latter Robinson’s official biographer. The ball player portrayed himself, while Ruby Dee played Rachel. It was filmed in California before the start of spring training in 1950 and released in May.

As a minor part of a larger strategy, the one-time comic magazine issue was likely not given much thought. The comic magazine was produced by Fawcett Publications of Greenwich, Connecticut, an independent newsstand distributor which also issued such popular magazines as True, True Confessions, and Woman’s Day, as well as a line of pocket-book originals under the Gold Medal Book label. The publisher also produced a run of comic books and was best known for introducing Captain Marvel in Whiz Comics #2, released in 1940.

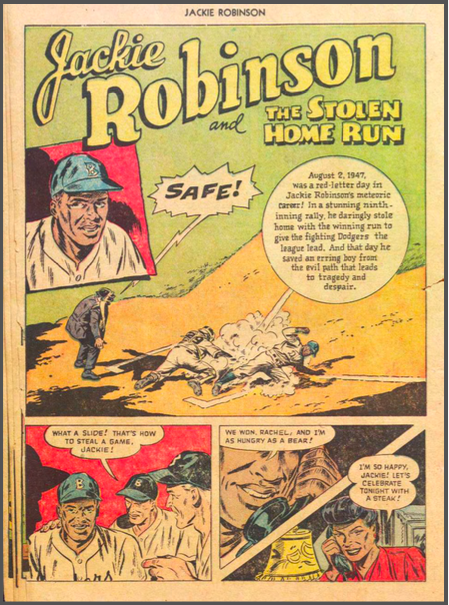

A page from one of the stories in Jackie Robinson comics, this one highlighting an August 1947 steal of home.

Jackie Robinson: Baseball Hero hit newsstands on September 23, 1949. The uncredited artwork was the responsibility of frequent Fawcett contributors Clem Weisbecker (pencils) and John Jordan (inks), whose work has been identified by experts in Golden Age comics. The script was the responsibility of baseball writer Charles Dexter.

The comic book’s storyline was likely borrowed from Robinson’s Jackie Robinson: My Own Story, released by the Greenberg publishing house in 1948. The as-told-to book was written by Wendell Smith, sports editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, who roomed with Robinson on the road in 1946 and 1947.

Either ignored or unknown by the publisher, let alone Robinson and his lawyer-agent, was Dexter’s background, which could have proved embarrassing and potentially devastating for Robinson’s financial and political future had it been revealed at an inopportune time.

Dexter was one of several pennames used by the writer, who had been a baseball reporter for the Daily Worker, a newspaper published by the Communist Party USA.

Dexter was born as Lewis Freiberg Levenson in 1895 in Rochester, New York, where his Russian immigrant father was a barber before opening a hair salon. Lew Levenson graduated from the Pulitzer School of Journalism at Columbia University before serving as a French translator with the rank of sergeant in the U.S. Army overseas during the First World War. After the war, he married Leola Brummer and worked as a movie and theatre press agent and wrote a few stage plays himself. Feature articles under his byline appeared in mainstream publications such as McCall’s, the New York Times, the New York World, the New York Herald-Tribune, and the Washington Post.

In 1932, he was lured to the West Coast to work for Columbia Pictures. After losing his Hollywood job two years later, Levenson helped organize beet workers in the state’s Imperial Valley, a time during which he likely became a Communist. He wrote an article for The Nation magazine describing dozens of incidents in which Latino labourers had been beaten by police and organized vigilantes during anti-Red raids. He also published Butterfly Man: The Untold Story of a Strange Love, a homophobic novel about a high-school athlete who succumbs to alcoholism after indulging in sexual decadence.

Back in New York by 1936, Levenson was hired by the Daily Worker, where he wrote reviews and arts features under his own name as well as such pseudonyms as “Annette Castle” and “Benjamin Cordozo.” As a sports reporter, he wrote under the names “Scorer” and “Charles Dexter.”

His identity as a Communist became newspaper fodder when he was hired as a publicist for the Federal Writers’ Project as part of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration. His hiring was criticized by conservative dailies, notably the Chicago Tribune, as well as by the Republican Party. One typical headline in an Indiana newspaper read: “WPA Writers’ project called hotbed of Reds.”4

He hid out in New Hampshire until the controversy simmered down, emerging to abandon the name Levenson in favor of Dexter. He covered the 1940 World Series between the Detroit Tigers and Cincinnati Reds as a Daily Worker correspondent. The following season, he was said to be the only one among nearly 300 members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America to have correctly predicted the Yankees winning the American League and the St. Louis Cardinals, Dodgers, and Reds finishing in that order in the National League.

In 1948, Dexter was subject to a strange indignity while covering a game at Yankee Stadium. During a rain delay in the fifth inning, a U.S. Treasury Department agent arrested and handcuffed him in the press box before taking him to a precinct in The Bronx. The writer was released without charge and returned to catch the end of the game in what he described as a case of mistaken identity.

Dexter contributed articles to the Dodgers’ yearbooks in 1941 and 1942, as well as selling articles about baseball to Collier’s, Baseball Digest, and the Saturday Evening Post. He was, as Jerome Holtzman of the Chicago Tribune described him in 1997 column, a “a wonderfully qualified baseball writer.”5

So, the business arrangement made sense. As well, the Daily Worker had been outspoken for more than a decade in promoting the integration of professional baseball. Even as Dexter was completing the comic book’s script, Robinson was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) on July 18, 1949, a week after the All-Star Game. Segregationists on the committee believed the civil rights movement was dominated by Communists and they sought Robinson’s testimony as a rebuke to statements made overseas by the great actor and athlete Paul Robeson. In Paris, Robeson made an anti-war statement regarded by much of the American press as traitorous.

Robinson’s testimony was widely praised, especially by White editorialists working for major daily newspapers. How different the reaction might have been had the committee asked about his business arrangements with a Daily Worker correspondent writing under a pseudonym.

The success of the first comic book led Fawcett to announce the title would appear as a regular bimonthly publication. Five more Jackie Robinson comics were issued, the final one appearing in 1952. Jackie Robinson #2 included articles in comic form on the 1947 World Series, Wilbert Robinson as a “Dodgers of Yesteryear,” a Robinson steal of home on August 29, 1947, his track career, and a two-page printed article about hitting technique without illustrations written by Dexter. Each issue was printed in the “hundreds of thousands,” according to promotional materials.

In 1950, Fawcett also released biographical comic books written by Dexter featuring Dodgers teammates Campanella and Don Newcombe. One of the more remarkable historical notes of these eight comic books was that these baseball titles featuring African American players were published only two years after what is regarded as the first known comic magazine written and drawn by African Americans. All-Negro Comics, founded by the journalist Orrin Cromwell Evans and issued in July 1947, lasted only one issue, as he was unable to find a wholesaler willing to sell him newsprint for a second issue.

Earlier in the year in March, the Parents’ Magazine Institute released Negro Heroes #1 featuring stories about Harriet Tubman and George Washington Carver. The next issue, released in 1948, featured Jackie Robinson on the cover.

Dexter and Robinson also collaborated on Robinson’s 1964 nonfiction book, Baseball Has Done It, in which he addresses baseball’s integration by interviewing other baseball players. Dexter is credited as editor of the publication, which included oral histories from Campanella, Newcombe, Henry Aaron, Monte Irvin, and Larry Doby, as well as some White southern players such as Alvin Dark.

The final panel of Jackie Robinson: Baseball Hero #6 features the player directly addressing the reader. He says: “There’s only one way to play the game, fellows! Play hard, play clean, play to win until the last man is out!”

TOM HAWTHORN is a senior writer for the government of British Columbia. He had a 40-year career as a newspaper and magazine writer in Canada, where he has served on the selection committees of two sports halls of fame. He is a frequent contributor to SABR publications.

Sources

Rampersad, Arnold. Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Ballantine Books, 1997).

Robinson Jackie, as told to Wendell Smith. Jackie Robinson: My Own Story (New York: Greenberg, 1948).

Robinson, Jackie, ed. by Charles Dexter. Baseball Has Done It (Philadelphia and New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1964).

Tygiel, Jules. Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and his Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

The six Jackie Robinson comic books issued by Fawcett can be read online here: https://comicbookplus.com/?cid=2885

Notes

1 Jackie Robinson: Baseball Hero (Greenwich, Connecticut: Fawcett Publications, [undated]). https://comicbookplus.com/?dlid=67936

2 Cathy Keen, “Jackie Robinson: Comic Book Hero,” https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/2013/06/jackie-robinson-comicbook-hero-42.html

3 Tex McCrary and Jinx Falkenburg, “TV showman plays to age groups.” Green Bay Press-Gazette (Green Bay, Wisconsin), July 30, 1951.

4 “WPA writers project called hotbed of Reds,” Times (Munster, Indiana), November 2, 1936.

5 Jerome Holtzman, “Cooperstown vote highly imperfect,” Chicago Tribune, January 7, 1997: B6.