Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting

This article was written by Peter Dreier

This article was published in Not an Easy Tale to Tell: Jackie Robinson on the Page, Stage, and Screen (2022)

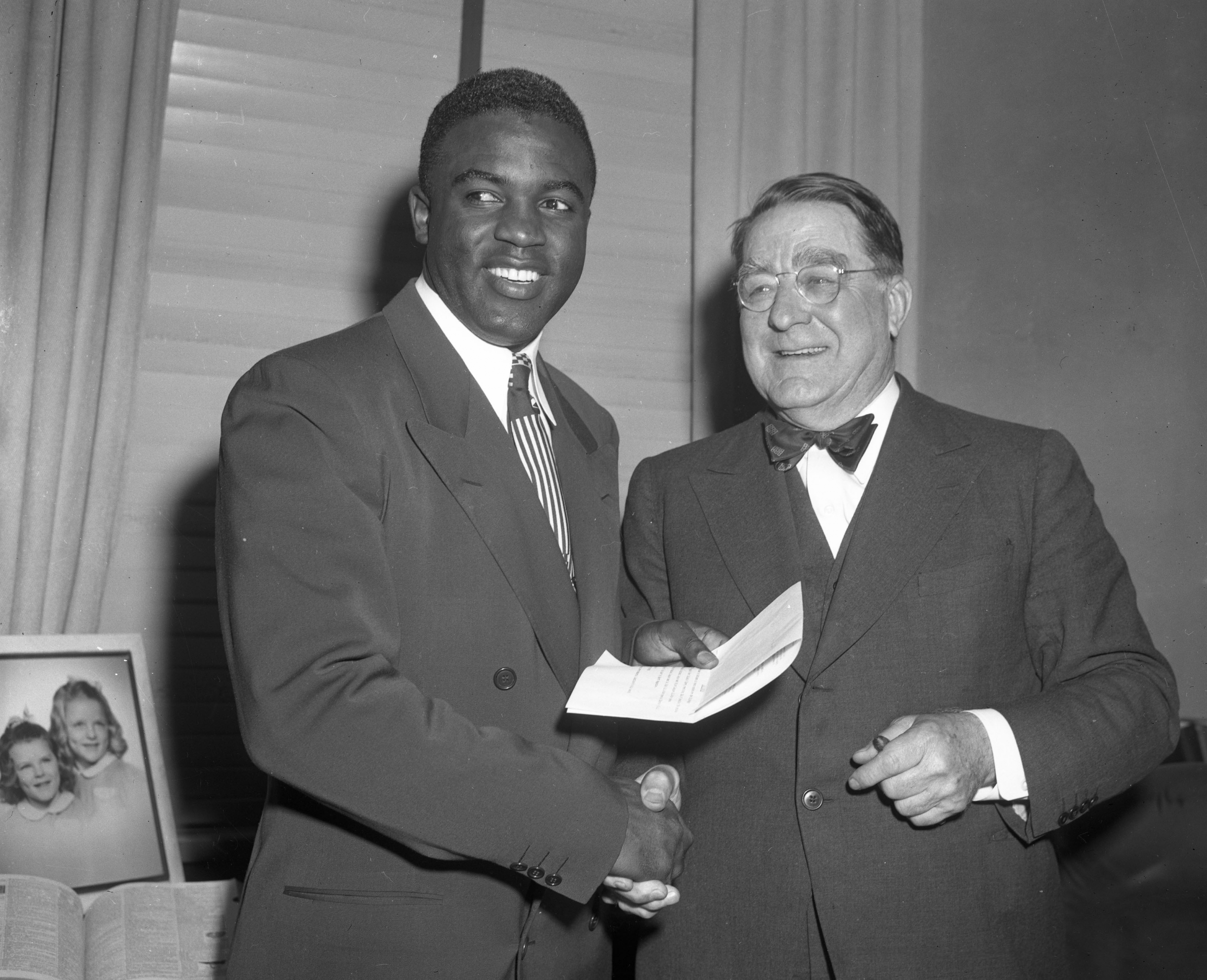

Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey talk happily after a contract signing meeting in the offices of the Brooklyn Dodgers in Ebbets Field on January 25, 1950. (SABR/The Rucker Archive)

In 1947, concerned about the firestorm that could erupt once he went public with his plan to break baseball’s color barrier by hiring Jackie Robinson, Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey believed that his effort would not succeed without the full support of the Black community. In Ed Schmidt’s play, Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting, Rickey invites Robinson and three beloved and prominent Black Americans—heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and actor-activist Paul Robeson—to a secret meeting in a room at New York’s Hotel Roosevelt on April 9, 1947, to solicit their public support.1 The entire one-act play takes place in that room, as each character voices his views about Rickey’s plan.

During the meeting, Rickey tells Louis, Robeson, and Bill Robinson that he won’t proceed with his plan without their unanimous support. The play revolves around Rickey’s effort to persuade the three men, who represented different and overlapping segments of the Black community, to embrace his plan.2 Each figure in the play had some history with the others. Each of three invitees was also facing personal problems at the time. As the play unfolds, Louis and Bill Robinson express support for Rickey’s plan, but Robeson raises objections regarding Rickey’s motives and his control as well as the potential demise of the Negro Leagues. The play pivots to the others’ reactions to Robeson’s ideas.

Schmidt’s play, written in 1989, debuted the following year at the Ironbound Theater in Newark, New Jersey. It was also staged at San Diego’s Old Globe Theatre and at the Pasadena Playhouse, in Robinson’s hometown, in 1997, the 50th anniversary of his breaking the color line. LA Theatre Works sponsored a live radio version of the play in 2004.3

Jackie Robinson

Rickey picked Robinson, a four-letter athlete at UCLA and a rookie with the Kansas City Monarchs, to integrate the major leagues over other more-established Negro League stars not only because of his athletic talent but also because he was young, educated, religious, and had experience dealing with inter-racial situations. Rickey knew Robinson had a hot temper and strong political views, but believed that he could handle the emotional pressure.

After signing Robinson to a minor-league deal in August 1945, Rickey assigned him to the Montreal Royals, Brooklyn’s top minor-league team, for the 1946 season, believing that he would face less racism in Montreal than in other minor-league cities. During the season, however, the Royals traveled to segregated cities like Louisville and Baltimore, where Robinson couldn’t stay in the same hotel or eat in the same restaurants as his white teammates.4 After Robinson led the International League with a .349 batting average and led the Royals to a triumph in the minor league World Series, Rickey intended to bring him up to the Dodgers for the 1947 season. He even moved the Dodgers’ spring training camp to Cuba, where Robinson would face less racist hostility than in Florida, where they usually trained.

Branch Rickey

Rickey was an unlikely candidate to dismantle baseball’s segregation system. He was politically and socially conservative. He opposed swearing or drinking alcohol. In his youth, he was active in the Anti-Saloon League, a temperance group. He occasionally made anti-Semitic and anti-Catholic comments.

Soon after he joined the Dodgers in 1942, Rickey began strategizing about challenging baseball’s color line. The question of why he did so has been the subject of much debate. Rickey viewed baseball in almost missionary terms, as a sport that enhanced American democracy and opportunity. He believed that segregation violated Christian principles.5 But Rickey often publicly denied that he was on a moral crusade. “My only purpose is to be fair to all people and my selfish objective is to win baseball games,” he explained.6

There were financial reasons motivating him as well. “The greatest untapped reservoir of raw material in the history of the game is the black race. The Negroes will make us winners for years to come.”7 Rickey believed that hiring Black players would boost attendance among the growing number of Black Americans who were moving from the South to the New York area during and after World War Two. Negro League teams were attracting large crowds when playing at the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium. The Brooklyn Bushwicks, a popular semipro team, drew their biggest crowds when they played Negro League teams.8

Rickey was a fervent anti-communist. In the late 1940s, he condemned ballplayers who jumped to the rival Mexican League for better pay as a “communist plot.” During the 1930s and 1940s, the Communist Party had gained influence in progressive circles, particularly among Black Americans in New York.9 Rickey knew that the Communist Party, its newspaper the Daily Worker, and leftist-led unions had been agitating to integrate baseball since the 1930s. He viewed the Negro press, led by the Pittsburgh Courier’s sports editor Wendell Smith, as allies in the cause. But Rickey did not want leftists to get credit for breaking the color line or to force his hand and his timetable.10

Rickey wanted to wait until early 1946 to make his announcement, but his hand was forced by New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s Committee on Baseball, which was about to issue a report calling on the three New York teams to hire Black players. Rickey did not want it to appear that he had signed Black players under pressure. He arranged for the Royals to introduce Robinson as the team’s newest member at a press conference in Montreal on October 23, 1945.

Joe Louis

Joe Louis reigned as heavyweight champion from 1937 to 1949. In 1938 he became a national hero for defeating German Max Schmeling, a symbol of Hitler’s Nazi ideology of Aryan supremacy, in a first-round knockout. Although the military was segregated during World War Two, Louis raised money for war bonds and helped recruit Black Americans to enlist. He first met Robinson when they were stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, a segregated Army base. Fort Riley officials refused to accept Robinson’s application for Officers Candidate School. Louis used his influence and within days after arranging a meeting for Robinson and other Black soldiers with a representative of the Secretary of War, Robinson was enrolled in OCS. That incident, not mentioned in the play, led to a personal relationship between Louis and Robinson.

His managers promoted Louis as “Bible-reading, mother-loving, God-fearing … and not… too black,” according to historian Jeffrey Sammons.11 Louis once remarked that his public image “made some whites begin to look at colored people different.”12

By 1947, at the time of the fictional meeting, Louis was still champion, but, at 32, well past his prime, overweight, and virtually broke. He saw only $800,000 of the $5 million grossed in his title fights. His handlers skimmed much of his income. Louis donated many of his purses to the war effort, but the IRS claimed that his income from those charity fights was taxable and harassed him for unpaid taxes.

Bill Robinson

Tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson was the most highly paid Black entertainer in the country during the first half of the twentieth century. He was sometimes criticized for performances that reflected undignified racial stereotypes, an accusation he strongly resented given the limited roles available to Black performers in his day. He was a racial pioneer – breaking barriers on Broadway, Hollywood, and radio. He often played to mixed-race audiences, was the first Black dancer to star in White vaudeville circuits, one of the first Black headliners to refuse to perform in blackface, and the first Black performer to appear in an interracial dance team in a Hollywood film – with Shirley Temple in The Little Colonel in 1935. (That scene, in which the two dancers hold hands, was removed for screenings in the South.) Robinson used his influence—persuading the Dallas Police Department to hire its first Black policeman, staging the first integrated public event in Miami, and lobbying President Franklin Roosevelt to improve the treatment and pay of Black soldiers during the war.

Robinson was a fervent New York Yankees fan. The team even enlisted him to quell the anger of New York’s Black residents after a Yankee player made overtly racist comments.13 In 1936 he was an original part-owner of the New York Black Yankees, a Negro League team that played most home games at Yankee Stadium. He was also one of two Black Americans that LaGuardia appointed to the 10-member committee to investigate racial segregation by the city’s three major-league teams. The committee’s work was stymied because one member (Yankees President Larry MacPhail) opposed the very idea and another member (Rickey) wanted to integrate the Dodgers on his own timetable without pressure from outsiders.14

Paul Robeson

Born in 1898 to a former runaway slave, Robeson starred in four sports at Rutgers, was twice named to the All-American football team, won Rutgers’ oratory award four years in a row, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and was valedictorian of his 1919 graduating class. He played professional football to pay his tuition at Columbia University law school but gave up practicing law to pursue a theater career. A highly successful film and stage actor, he also sang opera, show tunes, Negro spirituals, and international songs in 25 languages. His concerts drew huge audiences. During World War Two, he entertained troops at the front and sang battle songs on the radio.

Robeson was also a defiant radical. He gave free concerts for unions and progressive causes. He often refused to take roles that demeaned Black Americans, although some of his film roles reflected popular but negative stereotypes. In 1945 the NAACP awarded Robeson the Spingarn Medal, its highest honor.15

Robeson was an outspoken critic of European and American imperialism and a strong supporter of nations in Africa and elsewhere seeking to unleash themselves from the yoke of colonialism. He embraced the Soviet Union, which he believed had done more than his native country to battle racism and anti-Semitism. He denied being a member of the Communist Party, but he was clearly close to the party and shared many of its views.

In 1943 Robeson led a delegation of prominent Black Americans, including the owners of major Black newspapers, who met with baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Landis and team owners to demand the sport’s desegregation. “They said that America never would stand for my playing Othello with a white cast, but it is the triumph of my life,” Robeson declared at the meeting. “The time has come when you must change your attitude toward Negroes. Because baseball is a national game, it is up to baseball to see that discrimination does not become an American pattern. And it should do this this year.”16

In 1947, at the time of the play’s fictional meeting, Robeson was still a popular figure. but as the Red Scare widened, he became increasingly controversial. He was certainly aware that the walls were closing in on him. The FBI already had Robeson under surveillance for his outspoken views and his leadership of several organizations – the Council on African Affairs, the National Negro Congress, and the American Crusade Against Lynching—it considered “communist.”17 In October 1946, the Joint Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities in California – chaired by state Senator Jack B. Tenney – called Robeson to testify. Robeson would later face similar questioning from Tenney’s counterparts in Congress.18 As a hint of what was to come, a growing number of lecture and concert halls and public schools refused to allow Robeson to give concerts or deliver speeches on behalf of left-wing groups.

Compounding his problems, Robeson’s personal life, including his marriage, was in disarray. When the fictional meeting took place, he had recently ended an affair with White actress Uta Hagen, fearing that his career would be in jeopardy if publicly revealed.

Clancy Hope

One other character appears in the play. Schmidt uses Clancy Hope—a 17-year-old Black bellhop who brings food to the room—as a surrogate for the rank-and-file Black working class. Clancy (the play’s only fictional character) is awestruck by the men in the room, asking each for an autograph. He looks at Robeson: “You’re a Communist, ain’t you?” Robeson: “That seems to be the consensus.” Clancy: “My brother Cleveland, he’s nineteen. He tells me you’re a Communist. Cleveland says you’re the finest man alive.” Clancy’s view of Robeson illustrates why Rickey invited him to the meeting and why he fears Robeson’s influence.

The Carlton YMCA Meeting

The meeting depicted in the play is “almost certainly fictitious,” Schmidt wrote in his original program notes. In notes for the 1992 production, Schmidt clarified: “This meeting never took place.” It is unclear if Schmidt was aware that Rickey did have a meeting with Black leaders. It wasn’t a small gathering in a hotel room but a large assemblage at the Carlton branch of the YMCA in Brooklyn.

At Rickey’s request, YMCA executive Herbert T. Miller invited 30 Black leaders from Brooklyn to meet Rickey on the evening of February 5, 1947. The audience included lawyers, ministers, realtors, doctors and dentists, teachers, architects, morticians, business people, municipal employees, and other civic leaders. The only White people in the room were Rickey, NYU sociology professor Dan Dodson (who was helping Rickey with his integration plan),19 Edward Lazansky (a state Supreme Court judge), and Arthur Mann (a baseball writer and Dodger publicist).

The group expected to hear Rickey announce he was promoting Robinson to the Dodgers. Instead, he gave a long, paternalistic, and patronizing exhortation. He bluntly said that “if Jackie Robinson does come up to the Dodgers as a major leaguer, the biggest threat to his success—the one enemy most likely to ruin that success—is the Negro people themselves.”

He warned the group that “on the day that Robinson enters the big leagues—if he does—every one of you will go out and form parades and welcoming committees. You’ll strut. You’ll wear badges. You’ll hold Jackson Robinson Days…and Jackie Robinson Nights. You’ll get drunk. You’ll fight. You’ll be arrested. You’ll wine and dine the player until he is fat and futile. You’ll symbolize his importance into a national comedy…and an ultimate tragedy—yes tragedy!”20 Rickey concluded by outlining what needed to be done to prevent such behavior from “spoiling Jackie’s chances.”21

As Mann reported, the shocked group initially considered Rickey’s remarks “a sharp slap against every Negro face in the room.” But, by the end of Rickey’s talk, “the room broke into deafening applause.”22 Despite Rickey’s condescending attitude, the audience embraced his idea and formed a committee to carry out his plan. Their “Don’t Spoil Jackie’s Chances” campaign included churches, civic groups, and fraternal organizations in Brooklyn and Harlem. It urged Jackie’s supporters to exercise restraint, such as “If you’re drunk, don’t go to the ball game” and “Leave your liquor outside the ballpark.”23

There was no report of the meeting in either the mainstream or the Black newspapers.24

A Battle of Ideas and Personalities

The fictional meeting in Schmidt’s play between these disparate personalities is highly contentious. Robeson has a wider agenda beyond giving Robinson a chance to break baseball’s color line.

The play is a debate over different approaches to deal with racial injustice, through the lens of baseball. In this, the four Black figures echo a long-standing tension within the Black community, most prominently displayed in the debate between W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. They sharply disagreed about strategies for achieving racial and class justice, the role of Black leaders, and what the Black elite owed to the Black masses.

Robeson, the left wing radical, insists that collective action is more effective than the one-person-at-a-time up-by-the-bootstraps approach. Louis and Bill Robinson share some of Robeson’s views, but they are reluctant to undermine Jackie Robinson’s chances to become a baseball and racial pioneer. Jackie Robinson recognizes that if Robeson gets his way, he will lose his opportunity to join the Dodgers that season. Put in that awkward situation, Robinson ends up reluctantly defending an individualist approach to racial advancement.

Rickey’s paternalistic and patronizing attitude at the real YMCA meeting is reflected in his conversation with the four Black figures in the play. Rickey is used to being treated with deference. All of Rickey’s employees – ballplayers, managers, coaches, and office staff, White and Black – referred to him, in person and in the third person, as “Mr. Rickey.” Jackie Robinson would call him that even after Rickey died. Yet Rickey’s condescension is mixed with some concern for Robinson as an individual or as an asset, depending on how one interprets his comments.

At the start of the play, Rickey instructs Robinson about the behavior he expects, similar to how Joe Louis’s managers sought to control his behavior and image. In addition to avoiding any verbal or physical confrontations with players, Rickey tells Robinson that he should attend church, sign autographs, avoid going to nightclubs, return directly home after games, avoid being photographed with White women, and “no politics.” Although the Dodgers opening day game is less than a week away – April 15 – Robinson still doesn’t know if he’ll be sent back to Montreal or play with the Dodgers. But then Rickey opens his briefcase, retrieves a Dodgers jersey, and tosses it to Robinson. “You’re moving up to the varsity,” he tells him. “Congratulations, son. From this day forward, it’s Rickey and Robinson.”

Rickey tells Robinson that he wants the three visitors to believe that their opinions matter. He’s especially concerned about Robeson, telling Robinson that “The opposition he could generate if he’s not on our side—demonstrations, picket lines, dissension among the Negro ranks—could make life miserable for the both of us. So leave Robeson to me. If you lose your head and charge the mound on him, I’ll take the jersey back.”

When the three other men enter the room, they greet each other, and Robinson, warmly. Louis and Bill Robinson both know Rickey, but still call him “Mr. Rickey.” They are stunned when they hear Robeson greet him as “Branch.” It is the first sign that Robeson won’t easily acquiesce to Rickey. Schmidt depicts Robeson as proud, idealistic, and arrogant, unwilling to bend his principles. Although he initially focuses his criticism on Rickey, he challenges Jackie Robinson, Bill Robinson, and Louis for being too accommodating toward Rickey, which he views as a symptom of the larger problem of powerful White figures controlling Black lives. He chides Bill Robinson for being “subservient” and says that he made his money “actin’ the fool, playin’ the happy, grinnin’ darkie, then lost it all playing craps.” He tells Joe Louis, “You’ve let other people do your thinking for so long, you can’t think for yourself.”

In the play, Robeson views Rickey primarily as a profit-seeking businessman. Most Negro League players did not have formal contracts, agreeing to play for a specific amount by a handshake. Players switched teams from year to year. Rickey took advantage of this situation, failing to adequately compensate Negro League teams whose rosters he raided to populate the Dodgers and minor-league rosters. He didn’t pay the Kansas City Monarchs anything when he signed Robinson to a contract. Negro League owners were angry about Rickey – and later other major-league owners – poaching their talent. But wary of appearing opposed to racial integration, they muted their protests about the raids on their players.

Robeson tells Rickey, “With your stable of Negroes, the Brooklyn Dodgers will dominate baseball. But my concern is the fate of Bill’s team. What will become of his team? What will become of the Black Yankees?” This is the crux of Robeson’s argument: Whatever Rickey’s intentions—as a businessman and/or racial reformer—his plan would lead to the demise of the Negro Leagues and the livelihoods of its players and others who worked for the teams. “As they should be,” Rickey says. “Five years from now, if I have any say in the matter, the Negro Leagues will be dead and gone, and so will Negro bathrooms and Negro drinking fountains and Negro hotels.”

Robeson proposes instead that a Negro League all-star team, owned and run by Black Americans, be chosen to join the major leagues. Black players who aren’t picked can sign with another major-league team. “Finally, Negro League owners – like Bill – must be justly compensated for each and every ballplayer they lose and for the certain extinction of their league.” Rickey calls Robeson’s plan “Head-in-the-clouds, ignorant, arrogant, impractical idealism.”

Jackie Robinson interjects that Robeson’s proposal is “a waste of my time.”

“I understand your opposition, Jack,” Robeson responds. “You’re afraid you’re not good enough to make that elite Negro team.”

Robinson predicts that he’ll be the Rookie of the Year and then the Most Valuable Player, but Robeson says that there are at least 25 Negro League players who could do better. He named several athletes, including Monte Irvin, who most colleagues believed was the best player in the Negro Leagues at the time. 25 Robinson is clearly offended by that remark, having heard others, including Negro League players and owners, make similar comments. Rickey disputes Robeson’s baseball knowledge about these players, explaining why Robinson is the best choice.

But Robeson is making a larger point. He chides Rickey for wanting to be the “savior of the Negro race,” but only on his terms. “If it’s a World Series you want,” Robeson says, “then take all the Negroes. I guarantee you’ll win the World Series. Why only one? There are hundreds who deserve this chance.” Frustrated by the others’ unwillingness to challenge Rickey, Robeson loses his patience, looks directly at Robinson, and says, “And you just sit there in the corner with your mouth shut. Branch Rickey’s water boy.”

This gets a fierce reaction from Jackie Robinson. “What gives you the sonuvatchin’ right to lecture me?” say Robinson. “I’m not some United Auto Worker out on strike, or your comrade over in Russia, or one of the Broadway faithful who’s gonna stand up and cheer every time you open your mouth and sing your words of wisdom.” Robinson defends Bill Robinson and Louis as heroic Black men, but Robeson arrogantly dismisses that claim.

Robeson tells Louis and Bill Robinson that “We’re on different sides now! You are broke and beaten and pathetic because you let other people run your lives, but I never will.”

“I didn’t sell my soul,” Robeson continues. “I didn’t compromise. And I won’t until the day I die and damn everything else. I fought this battle for years. I demanded the integration of baseball while you were still in college, young Jack Robinson. They have never beaten me.”

“And you have never beaten them,” Robinson answers, finding his voice in response to Robeson’s baiting, expressing the fury that made him a successful athlete and activist. “But I will. Mr. Rickey’s the one who opened the door, but I’m the one walkin’ out the room… See, I know this isn’t about spoiling Jackie’s chances. It’s about Clancy’s chances, and my kid’s, and his. I’m gonna catch all the shit they have to throw our way, and then I’m going’ back into that Colored Only Room and I’ll carry every single goddamn person out on my back.”

Jackie Robinson, who had admired Robeson despite their political differences, now views him differently and defiantly. He tells Robeson, “I don’t want to end up like them. But I sure as hell don’t want to end up like you. You fought the battle all right, you just forgot who the enemy was. Dropped a bomb on your own troops.”

Rickey leaves the room after young Clancy Hope told him that a representative of the Commissioner’s office wanted to meet with him. That was a ruse, orchestrated by Louis. By the end of the play, Louis, Bill Robinson, and Robeson had still not voted on Rickey’s plan. When Rickey comes back—after realizing that one or more of his guests had fooled him into leaving—he finds the door locked. None of the others bothers to open it and Rickey is stuck outside. When he threatens Clancy Hope, warning that he’ll get him fired from his hotel job, the young bellhop tells Rickey, “You do it and you can go straight to hell.”

Robeson leaves the meeting without saying goodbye to the others. Bill Robinson and Joe Louis tell Jackie Robinson that they support his promotion to the Dodgers. As the three are about to leave together, Bill Robinson looks at Clancy and calls him “the bravest man I ever met. He did what no man ever done. He told Branch Rickey to go to hell.” Jackie Robinson asks Clancy to “tell Mr. Rickey I went home. And tell him I’ll be in uniform tomorrow.”

The 28-year-old Robinson is about to begin his illustrious career in the major leagues. And the 17-year-old Clancy Hope, who has overheard these leading Black figures debate how to respond to White racism, has found his voice, learning from Robeson to speak up against a powerful white figure. We don’t know what happens to Clancy, but we can imagine that he’d somehow be involved in the next two decades of civil rights activism.

Aftermath

Most Black Americans welcomed baseball’s integration as they later welcomed the end of separate drinking fountains and segregated buses, parks, and schools. But their enthusiasm was mixed with recognition that opening the major leagues to Black players would sooner or later devastate the Negro Leagues and lead to a loss of jobs for players, stadium workers, and others.

Robinson’s predictions about himself came true. In 1947, he was selected as the Rookie of the Year. That year, the Dodgers set road attendance records in every National League park except Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. Two years later, he won the National League’s Most Valuable Player Award. An outstanding base runner, with a .311 lifetime batting average, he led the Dodgers to six pennants and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1962.

The tension between Robinson and Robeson depicted in the play is reminiscent of a real encounter between the two men. In July 1949, segregationist Congressman John Wood of Georgia, a former Ku Klux Klan member who chaired the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), invited Robinson to address a hearing on “Communist infiltration of minority groups.” Specifically, Wood wanted Robinson to attack Robeson for being a disloyal American and Communist agitator who didn’t speak for Black people. The media salivated at the opportunity to portray the clash of these larger-than-life titans as a surrogate for the Cold War between capitalism and communism.

Although he didn’t agree with Robeson’s Communist views, Robinson was reluctant to testify against Robeson. “I didn’t want to fall prey to the white man’s game and allow myself to be pitted against another black man,” he later wrote. “I knew that Robeson was striking out against racial inequality in the way that seemed best to him.”26

On July 18, as expected, Robinson criticized Robeson, but it was far from the harsh attack that Wood and his HUAC colleagues had hoped for. Instead, Robinson challenged America’s racial hypocrisy and made an impassioned demand for integration. Robinson said that Robeson “has a right to his personal views, and if he wants to sound silly when he expresses them in public, that is his business and not mine. He’s still a famous ex-athlete and a great singer and actor.”27 Robinson insisted that Blacks were loyal Americans who would “do their best to help their country stay out of war. If unsuccessful, they’d do their best to help their country win the war—against Russia or any other enemy that threatened us.”28

Robinson’s appearance was a major news story, but the press focused on his criticism of Robeson and virtually ignored his condemnation of racism. It was part of a wider campaign to isolate Robeson, who was denounced by the media, politicians, and conservative and liberal groups alike as being a traitor and Soviet shill. Radio stations banned his recordings. Concert halls and colleges cancelled his performances.

In 1950, the State Department revoked Robeson’s passport so he couldn’t perform abroad, where he was still popular. His annual income plummeted from over $150,000 to less than $3,000. His name and photo were even stricken from the college All-America football teams. His voice was marginalized during the 1960s civil rights movement. He died a lonely and broken man on January 23, 1976, at age 77.

In his 1972 book, Robinson apologized to Robeson, writing that he wished he had rejected HUAC’s invitation to testify against him. “I have grown wiser and closer to the painful truths about America’s destructiveness, and I do have an increased respect for Paul Robeson, who, over the span of that 20 years sacrificed himself, his career and the wealth and comfort he once enjoyed because, I believe, he was sincerely trying to help his people.”29

In 1950, Walter O’Malley gained control of the Dodgers, purchased Rickey’s shares, and pushed him out as Dodger president. The following season, Rickey became the Pittsburgh Pirates’ general manager, stepping down after the 1955 season. His plan to start a third league, the Continental League, never got off the ground. He died on December 9, 1965, 11 days before his 84th birthday. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1967.

During his life, Bill Robinson was a benefactor to many charities and frequently donated money to complete strangers facing hard times. He lost much of his fortune at the racetrack. By the time of the play’s fictional meeting, he was virtually penniless, a result of his “love of luxury, his extreme generosity, and his undiminished penchant for gambling.”30 At the end of the 1947 season, the Dodgers invited him to attend a Jackie Robinson Day celebration where he presented Robinson and Rachel with keys to a new car. Bojangles told assembled reporters, “I never thought I’d be around to honor a Ty Cobb in Technicolor.”31 He died penniless on November 25, 1949, of heart failure. Harlem schools were closed for a half-day so that children could attend or listen to the funeral over the radio.

Louis kept fighting long after his boxing skills had eroded. He announced his retirement on March 1, 1949. After the IRS told him that, with interest and penalties, he owed the government over $500,000, he kept fighting until 1951, when Rocky Marciano knocked him out. To make money, the desperate Louis became a professional wrestler, appeared on TV quiz shows, took a job greeting tourists at Caesars Palace hotel in Las Vegas, and refereed wrestling matches until 1972. Friends and admirers helped Louis pay off some of his debts.

Louis died of cardiac arrest on April 12, 1981. In 1982, Louis was posthumously given the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest award Congress bestows on civilians. People often said that Louis was “a credit to his race.” New York Post sportswriter Jimmy Cannon responded: “Yes, Joe Louis is a credit to his race—the human race.” In 1954, Jackie said: “I certainly feel that the path for me and others to the big leagues was made easier by the performance and conduct of Joe Louis both in and out of the ring. All of us should give Joe a pat on the back for creating a favorable atmosphere.”32 On another occasion, Robinson observed, “I’m sure if it wasn’t for Joe Louis the color line in baseball would not have been broken for another 10 years.”33

The predictions Robeson made in Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting were also accurate. In 1947 about 311 players filled the rosters of the 12 Negro League teams.34 By the end of the 1953 season, only 35 former Negro League players had reached the major-league level.35 The demise of the Negro Leagues destroyed the careers of many Black ballplayers.36 Without the same fanfare that greeted Robinson, some former Negro League players signed contracts and served as pioneers, integrating major- and minor-league teams, which was particularly rough in many Southern cities and towns.37 Many of them languished in the minors for years without ever advancing to the majors.

The quality of Negro League play suffered, as did attendance. In his syndicated column on May 29, 1947, Dan Parker noted that while record crowds attended the New York Giants game at Polo Grounds to watch Robinson, a Negro League game across the river at Yankee Stadium attracted a small crowd.38 In 1948, the Negro National League – including Bill Robinson’s New York Black Yankees – folded. The Negro American League collapsed around 1960. By 1966, the Indianapolis Clowns were the only former Negro League team still playing, primarily by staging exhibition games against local teams, peppering the games with humorous antics, similar to the Harlem Globetrotters basketball team. The Clowns called it quits in the 1980s.

By 1959, Black ballplayers comprised 10 percent of major league players, reaching 20 percent by the mid-1960s. Black ballplayers who pioneered integration in the 1950s learned that simply making it to the majors didn’t mean an end to the racial discrimination and segregation they would continue to face in baseball and in the wider society, including the segregation of spring training facilities and the fact that in many cities Black ballplayers couldn’t stay in the same hotels, eat in the same restaurants, or take the same taxis as their white teammates.

Jackie Robinson’s legacy is not simply that he was the first African American to play in the major leagues in the 20th century. He viewed himself as much an activist as an athlete. He recognized that his opportunity to break baseball’s color line was the result of a protest movement and he repaid that debt many times over through his own participation in the struggle for civil rights. The recent upsurge of activism around racial justice among professional athletes, including baseball players, is part of that legacy.39

Robinson believed that as an American citizen, and as a Black man in a racist society, he had an obligation to use his fame to challenge the social and political status quo. Years before Colin Kaepernick was born, Robinson wrote: “I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world.”40

PETER DREIER is the E.P. Clapp Distinguished Professor of Politics at Occidental College. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Nation, American Prospect, Dissent, Huffington Post and many other publications, including scholarly journals. He has written or edited eight books. Two books co-authored with Robert Elias – Baseball Rebels: The Players, People and Social Movements That Shook Up the Game and Changed America and Major League Rebels: Baseball Battles Over Workers’ Rights and American Empire – were published in April 2022.

Notes

1 Robinson played his first game as a Dodger a week later, on April 15, 1947.

2 New York’s Black elite was a relatively small world of overlapping social circles. Bill Robinson and Robeson lived in the same housing complex – the 511-unit Dunbar Apartments in Harlem, built in 1926, which was also home at different times to W.E.B. Du Bois, poet Countee Cullen, bandleader Fletcher Henderson, union leader A. Philip Randolph and explorer Matthew Henson. Jim Haskins and N.R. Mitgang, Mr. Bojangles: The Biography of Bill Robinson (New York, Linus Multimedia, 2014), 191. See also Matthew Gordon Lasner, “Housing To Remember: The Paul Laurence Dunbar Apartments,” Gotham Center for New York City History, March 28, 2017 https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/housing-to-remember-the-paul-laurence-dunbar- In the 1930s, Louis and Robeson both lived in another Harlem apartment building at 555 Edgecombe Avenue. See Paul Hond, “Bittersweet,” Columbia Magazine, Winter 2016-2017. https:// magazine.columbia.edu/article/bittersweet and “DIY Walking Tour: Historic Harlem Homes,” The Curious Uptowner, n.d. https://www.thecuriousuptowner.com/post/diy-walking-tour-historic-harlem-homes. In 1941, Robeson recorded a song about Louis, “King Joe,” with lyrics by Richard Wright and music by Count Basie. See David Margolick, “Only One Athlete Has Ever Inspired This Many Songs,” New York Times, February 25, 2001. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/02/25/arts/music-only-oneathlete-has-ever-inspired-this-many-songs.html

3 The LA Theatre Works performance is available in CD format. https://www.audiobooks.com/audiobook/mr-rickey-calls-a-meeting/210100

4 Despite these difficult circumstances, Robinson led the International League with a .349 batting average and 113 runs, finished second with 40 stolen bases, and led the team to a 100-54 season and a triumph in the minor league World Series.

5 Allen St. John, “There Was Another Side to the Color Line: Green,” Los Angeles Times, March 30, 1997. For Rickey’s motives, see Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007).

6 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983, 52

7 John McMurray, “Branch Rickey Revolutionized Baseball In More Ways Than One,” Investors Business Daily, April 12, 2017. https://www.investors.com/news/management/leaders-and-success/branch-rickeyrevolutionized-baseball-in-more-ways-than-one/; Allen St. John, “There Was Another Side to the Color Line: Green,” Los Angeles Times, March 30, 1997.

8 Thomas Barthel, Baseball’s Peerless Semipros: The Brooklyn Bush-wicks of Dexter Park (Harworth, New Jersey: St. Johann Press, 2009).

9 Mark Naison, Communists in Harlem During the Depression (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2004); and Mark Solomon, The Cry Was Unity: Communists and African Americans, 1917-36 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998).

10 Peter Dreier, “Before Jackie Robinson: Baseball’s Civil Rights Movement,” in Bill Nowlin and Glen Sparks, editors, Jackie: Perspectives on 42, Society for American Baseball Research, 2021, 27-37. https://sabr.org/research/article/before-jackie-robinson-baseballs-civil-rights-movement/ On Rickey’s concern about communists, see Dan Dodson, “The Integration of Negroes in Baseball.” Journal of Educational Sociology, Vol. 28, No. 2 (October 1954), 73-82. On the protest movement to integrate baseball, see Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment; Chris Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012); Irwin Silber, Press Box Red: The Story of Lester Rodney, the Communist Who Helped Break the Color Line in American Sports (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003); Kelly Rusinack, “Baseball on the Radical Agenda: The Daily Worker and Sunday Worker Journalistic Campaign to Desegregate Major League Baseball, 1933-1947,” in Joseph Dorinson and Joram Warmund, editors, Jackie Robinson: Race, Sports, and the American Dream (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1998); David K. Wiggins, “Wendell Smith, The Pittsburgh Courier-Journal and the Campaign to Include Blacks in Organized Baseball 1933-1945,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Summer 1983): 5-29; Henry Fetter, “The Party Line and the Color Line: The American Communist Party, the ‘Daily Worker,’ and Jackie Robinson,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Fall 2001): 375-402; Lowenfish, Branch Rickey, and Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson (New York: Ballantine Books, 1997).

11 Sammons’ comment is from a PBS documentary, The Fight, about Louis and Schmeling, cited in Ned Martel, “Schmeling and Louis, Body and Soul,” New York Times, October 18, 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/18/arts/television-review-schmeling-and-louis-body-andsoul.html

12 Quoted in Ira Berkow, Counterpunch: Ali, Tyson, the Brown Bomber, and Other Stories of the Boxing Ring (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2014), 38.

13 Ray Robinson, “When Bojangles Came to the Yankees’ Defense,” New York Times, August 22, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/23/sports/baseball/23bojangles.html

14 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 276; Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence, 275.

15 The following year, after four African Americans were lynched in Georgia, Robeson led a delegation that urged President Harry Truman to support legislation to end lynching, admonishing the president that “the Negroes will defend themselves” if threatened by mob violence. Truman told Robeson that, in the middle of a war, the time was not right to pass such divisive legislation. Robeson disagreed and founded the American Crusade Against Lynching, co-chaired by scientist Albert Einstein, to pressure Truman and Congress, but their efforts were unsuccessful.

16 Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson (New York: The New Press, 1995), 282-283; Wendell Smith, “Publishers Place Case of Negro Players Before Big League Owners: Judge Landis Says No Official Race Ban Exists in Majors,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 11, 1943: 1.

17 Duberman, Paul Robeson, 296-335.

18 Duberman, Paul Robeson, 307-309.

19 See Dodson, “The Integration of Negroes in Baseball.”

20 Arthur Mann, The Jackie Robinson Story (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1963), 160-65. This meeting is also mentioned in Milton Gross, “The Emancipation of Jackie Robinson,” Sport, October 1951, and A.S. (Doc) Young, “Jackie Opens the Door,” Ebony, December 1968. References to the YMCA meeting in subsequent books and articles rely on Mann’s first-person account and those by Gross and Young.

21 Mann, The Jackie Robinson Story, 164.

22 Mann, The Jackie Robinson Story, 162.

23 Mann, The Jackie Robinson Story, 164-65.

24 Dodson, “The Integration of Negroes in Baseball.”

25 According to Roy Campanella, “Monte was the best all-round player I have ever seen. As great as he was in 1951, he was twice that good 10 years earlier in the Negro Leagues.” Many Negro League owners and players as well as Black sportswriters shared Campanella’s opinion. Irvin also had other qualifications, including a college education (Lincoln College) and military service, that Rickey was looking for. He was the same age as Robinson, although he had suffered a knee injury from which he never fully recovered. When he came up to the majors in 1949, Irvin acknowledged that “this should have happened to me 10 years ago. I’m not even half the ballplayer I was then.” Larry Hogan, “Monte Irvin,” SABR bio project https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/monte-irvin. Irvin told Joe Posnanski that Dodger scout Clyde Sukeforth made him an offer to become the first Black player in the majors, but he declined the offer because he didn’t think he was ready for that pioneering role. Joe Posnanski, The Baseball 100 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021), 203. He explained to Peter Golenbock that his three years of service in World War 2 had been too hard on him. “I hadn’t played at all. That war had changed me.” Peter Golenbock, In the Country of Brooklyn (New York: William Morrow, 2008), 148. He told Jeff Idelson that being in a segregated Army unit during the war “affected me both mentally and physically.” He said that “Jackie was the right person.” Jeff Idelson, “An Interview with Monte Irvin,” Baseball Hall of Fame, n.d. https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/baseball-history/interview-with-monte-irvin-2006

26 Jackie Robinson with Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: HarperCollins, 1995; original published in 1972), 85-86.

27 Transcript of Robinson’s testimony: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31210019443231&view=1up&seq=37.

28 Transcript of Robinson’s testimony.

29 Peter Dreier, “Half a Century Before Colin Kaepernick, Jackie Robinson Said, ‘I Cannot Stand and Sing the Anthem,’” The Nation, July 18, 2019. https://www.thenation.com/article/huac-jackie-robinson-paulrobeson/

30 Haskins and Mitgang, Mr. Bojangles, 216.

31 “Brooklyn Honors Jackie Robinson,” Paterson (New Jersey) Morning Call, September 24, 1947.

32 “Jackie Acclaims Joe Louis at Howard Fete,” Afro-American, February 13, 1954.

33 Quoted in Randy Roberts, “Joe Louis: ‘You Should Have Seen Him Then,’” in Gerald Early, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Boxing (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 184.

34 Calculated from annual rosters in Dick Lark and Larry Lester, editors, The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland, Ohio: Society for American Baseball Research, 1994).

35 Calculated from data and examples in Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959 (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1994); Rick Swaine, The Integration of Major League Baseball: A Team by Team History (Jefferson, North Carolina: Mc-Farland & Company, 2009); and Steve Jacobson, Carrying Jackie’s Torch: The Players Who Integrated Baseball – and America (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2007).

36 August Wilson’s play Fences reflects the frustration and anger of Negro League players whose careers ended after the integration of the major leagues. See Peter Dreier, “Denzel Washington Brings August Wilson’s ‘Fences’ To the Screen,” American Prospect, January 6, 2017 https://prospect.org/culture/denzel-washington-brings-august-wilsons-fences-screen

37 Bruce Adelson, Brushing Back Jim Crow: The Integration of Minor-League Baseball in the American South (Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 1999); Amy Essington, The Integration of the Pacific Coast League: Race and Baseball on the West Coast (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018).

38 Dan Parker, “Robinson Attracts Negro Fans,” Camden Courier-Post, May 29, 1947.

39 Peter Dreier and Dave Zirin, “Making Black Lives Matter On and Off the Diamond,” The Nation, September 30, 2020 https://www.thenation.com/article/activism/blm-mlb-logo-baseball/; Peter Dreier, “Will Major League Baseball Confront Its Racist Past?” Dissent, July 22, 2020 https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/will-the-mlbconfront-its-racist-history; Peter Dreier, “Athletes’ Racial Justice Protest Last Week Made History. But It Wasn’t the First Wildcat Strike in Pro Sports,” Talking Points Memo, September 3, 2020

https://talkingpointsmemo.com/cafe/athletes-racial-justice-protest-history-wasnt-first-wildcat-strike-pro-sports; Dave Zirin, The Kaepernick Effect: :Taking a Knee, Changing the World (New York: The New Press, 2021)

40 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made (New York: Harper Collins, 1995) (originally published in 1972), xxiv.