Greenlee Field (Pittsburgh)

This article was written by Jeb Stewart

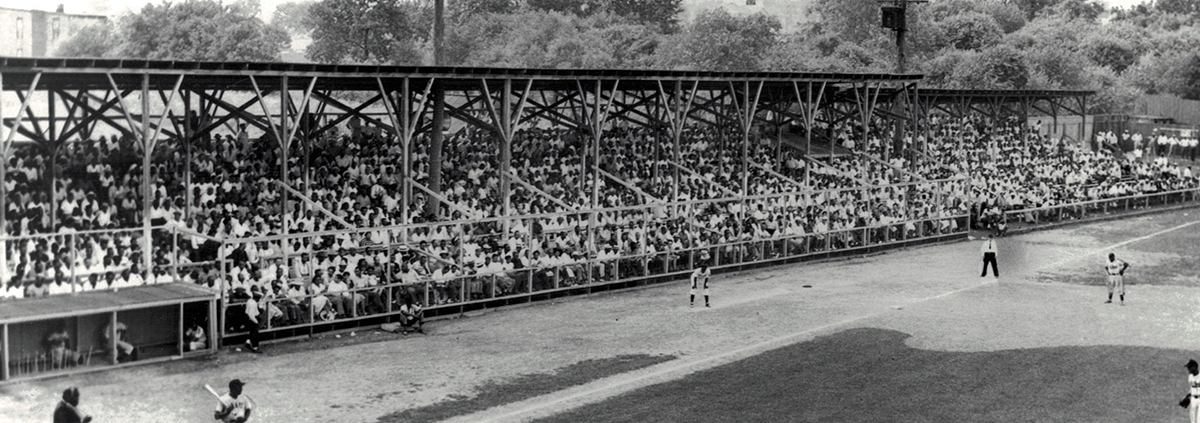

Greenlee Field, located in the 2500 block of Bedford Avenue, had its official opening on April 29, 1932, when the Crawfords hosted the New York Black Yankees and lost a tough 1-0 game. (NOIRTECH RESEARCH, INC.)

In 1931 the United States economy was drowning in the sea of the Great Depression, which brought nearly every industry in the nation to a standstill. The ripple effects of the crisis hit Pittsburgh’s black community particularly hard as thousands were out of work and unable to meet financial commitments.1 So, it was remarkable when William “Gus” Greenlee, a benevolent racketeer, built a baseball park on Bedford Avenue in Pittsburgh’s Hill District to serve as the home of the Pittsburgh Crawfords. Greenlee Field was truly a Depression-era facility during its short life, which ended abruptly when it was torn down in 1938. The fate of the park, the Crawfords, and Gus Greenlee’s involvement in the Negro Leagues were intertwined during this period.

Gus Greenlee grew up in North Carolina. His three brothers went into the medical and legal professions, while Greenlee was a college dropout who found his calling in the underworld.2 His first documented crime occurred in 1916, when he hopped a freight car from North Carolina to Pittsburgh.3 He drove a taxi and became a bootlegger during Prohibition. Eventually Greenlee became a powerful figure in the numbers and loan-shark rackets in the Hill District.4 He ran his empire out of the Crawford Grill on Wylie Avenue and made a fortune, reportedly earning up to $25,000 in a single day.5 Surely Greenlee must have realized he needed to find legitimate investments. Owning a professional baseball club and constructing a ballpark presented him with an easy opportunity to launder money from his criminal enterprises.6

Pittsburgh Courier columnist John L. Clark helped organize the Crawfords to represent the Crawford Recreation Center in the mid-1920s.7 He promoted the players and worked tirelessly to raise money to buy equipment. Clark soon became friends with Greenlee. Using the power of his column, he became Greenlee’s “part-time publicist.”8 It was a natural marriage of personal and financial interests when Clark persuaded Greenlee to become the Crawfords’ benefactor in 1930.9

After acquiring a principal ownership stake in the Crawfords, Greenlee provided baseball uniforms and a $10,000 bus for travel.10 He decided to not just compete, but dominate Negro League baseball, much to the ire of Homestead Grays owner Cum Posey. During his relatively short tenure as owner, Greenlee assembled a Who’s Who of black baseball’s best players and future Hall of Famers, which included at various times: Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Judy Johnson, Cool Papa Bell, Bill Foster, and Jud Wilson.

According to Clark, who added the titles of Crawfords publicity director and secretary to his duties as a columnist,11 Greenlee quickly became disenchanted with having to rent facilities for home games. Many ballparks were inadequate, and others were simply expensive, including Forbes Field.12 At Forbes, the players suffered the further indignity of not being allowed to use the clubhouse.13 Greenlee solved these problems by building his own ballpark. He knew that putting it in the Hill District would help the Crawfords build a following among residents of the area.14 Creating a fanbase was a critical step in competing against Posey’s established Grays in what sportswriters were already describing as a “baseball war.” 15

In 1931 Greenlee found an ideal parcel of land on Bedford Avenue, where the Entress Brick Company had its operations. He was opportunistic in his choice; the company was in financial distress, which saved him money on the acquisition. Clark recalled:

“Greenlee began negotiations with Dr. Toms, principal stockholder of the Entress Brick and owner of the land. Zoning restrictions were modified, and the project approved by Lincoln cemetery, situated on the west and the Municipal hospital on the east. The corporation was set up, with Dr. Toms, president; Joe Tito, treasurer, and Robert F. Lane, secretary. W.A. Greenlee, owning 25 per cent of the stock, held no office. The operating company was known as the Bedford Land Company.”16

A black architect, Louis Arnett Stuart Bellinger, designed Greenlee Field,17 which made it one of the few baseball parks designed and constructed by African-Americans for a Negro league team. The reported cost of construction was $100,000, which was an exorbitant sum to spend on an entertainment venue during the Depression.18 Grandstand seats were originally priced at 50 cents, while access to the bleachers cost 35 cents.19

Greenlee located the park “in the 2500 block [of] Bedford Avenue between Junilla and Watt Streets,” with an enclosure around the field.20 The capacity of the concrete and steel grandstand was initially reported as 5,000. Additional bleachers were placed between right and center field, which may have seated an additional 1,000 patrons;21 later reports suggested between 7,000 and 7,500 fans could attend baseball games.22 As a boxing arena, 10,000 seats accommodated spectators.23 By November, the ballpark became a true multisport facility, which could expand to 15,000 for football.24 In December 1933, Greenlee Field also served an important civic role in the community as the site of protests against the trial of the falsely accused Scottsboro Boys.25

The interior was modest but included dugouts for both sides. A brick veneer extended along the interior of the grandstand from the third-base side to the edge of right field.26 Although there were restrooms for fans,27 other aspects were spartan. There was no roof over the stands, so spectators experienced the same elements as the players;28 while there may have been some seats with backs, aerial photographs suggest most of the available seats were bleachers. The clubhouses were located under the first-base stands, and the Crawfords’ offices were incorporated as a two-story building beneath the home-plate stands facing Bedford Avenue.29

The Pittsburgh Press reported the planned outfield dimensions as 375 feet in left field, 345 in right, and a massive 500 feet to dead center. Geri Strecker’s The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field: Biography of a Ballpark is the gold standard of its history.30 Strecker left no stone unturned in her comprehensive research. Using aerial photographs, she calculated the actual distance of the fences as 342 in left, 338 in right, and 410 in center, which was similar to Shea Stadium’s outfield.31 Using the same method, it appears the backstop was approximately 55 to 60 feet from home plate. The photos show about 25 feet of foul territory on the first-base side, which narrowed to roughly 15 feet down the right-field line.

In right field, a row of trees stood between the bleachers, which were pressed against an eroding hill, and the Municipal Hospital, perched above the field and its meandering wooden fence. Just over the left- and center-field fences was a steep hill, which stretched several hundred feet down. Beyond the third-base stands, the foul territory was much larger and probably measured up to 60 feet from the baseline to an unkempt hill, and another 30 feet from there to the exterior fence, which marked the boundary with Lincoln Cemetery.

The most recognizable aspect of Greenlee Field was the exterior brick façade, which began at the Crawfords offices and “extended the full length of Bedford Avenue between Junilla and Watt Street.”32 In the Crawfords’ most famous photograph, the players are kneeling in front of their bus, with the façade in the background. A ticket window appears on the left of the picture next to three archways where fans entered. A sign in the photograph advertised a championship boxing match between Charlie Massera and John Henry Lewis, whom Greenlee managed.

The 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords team photo shows the exterior of Greenlee Field, with its brick façade and three arched entryways. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

While excitement was building for the opening, the Crawfords held their 1932 spring training in Hot Springs, Arkansas, and then played exhibition games across the Midwest and South on their way home.33 The Sports Fans of Pittsburgh announced a dance and reception at Princess Hall, along with a parade, as part of the official dedication on April 29.34 The Crawfords unofficially opened the ballpark on April 28 by thumping a local amateur team, the Vandergrift Baseball Club, 11-0.35

The next day Greenlee Field officially opened with 4,000 fans reportedly in attendance. Chester L. Washington was sufficiently impressed by the opening to feature it in his Sportively Speaking column, writing:

“All the color, glamour and picturesqueness that usually attends the opening of a big league ball park was in evidence as Goodsen’s New York Black Yankees helped the popular Pittsburgh Crawfords dedicate the attractive new Greenlee Park here Friday. Photos of both teams were taken … the band played … an impressive dedicatory speech was made by attorney R.L. Vann, during which the spectators stood to pay homage to Gus Greenlee, builder of the park. … [B]oth teams paraded to deep center field, led by Charley Stewart, Mr. Vann and the band, where the American flag and the Crawford pennant were raised to zephyr-like breezes. … Attorney Vann strode to the plate and dramatically pitched out the first ball … the electrified radio amplifiers announced the batteries – and the game was on.”36

After the pregame festivities, player-manager Oscar Charleston gave Satchel Paige the honor of starting against the Black Yankees.37 Had Josh Gibson started at catcher, the duo arguably would have formed the greatest battery ever to open a stadium. However, Bill Perkins got the start behind the plate and Gibson played in left field.38 The Black Yankees countered with Jesse Hubbard, a tall right-hander from Texas, who had pitched in the Negro leagues since 1919.

For eight innings, Hubbard and Paige dueled; Paige struck out 10 and allowed six hits, while Hubbard allowed three hits, and the game remained scoreless.39 In the top of the ninth, the Black Yankees finally scratched out a run. With one out, Orville Riggins singled and Ted Page’s fielder’s-choice grounder forced him at second. Page stole second and advanced to third on Perkins’s throwing error. A bloop single by Thomas40 brought Page home and the Black Yankees led 1-0.41 In the bottom of the ninth, the Crawfords made two quick outs, and Josh Gibson was Pittsburgh’s last hope: “The mighty Gibson sent a terrific clout to deep center field that looked for an instant like an extra base hit, but the fleet footed Thomas was away with the crack of the bat and gathered in the speeding pellet and the first pitchers’ battle was over.”42

Despite the Opening Day loss, the Crawfords bounced back and played well as an associate member of the East-West League. The highlight of the campaign undoubtedly occurred on July 15 at Greenlee Field. With Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe behind the plate, Satchel Paige threw a no-hitter against the Black Yankees.43 Remarkably, Paige overcame seven errors by his fielders in the 6-0 win.

In August the Crawfords hosted their first night game, against the House of David.44 By September, the always innovative Greenlee made the lights permanent several years before major-league ballparks did the same.45 The lights proved useful that month when the Crawfords and Grays experimented by starting a game at midnight on a Monday to circumvent Pittsburgh’s ban on Sunday baseball.46 Paige later recalled that the crowd “jammed the park” that night.47

Historian Jim Bankes credited the Crawfords with 99 wins in 1932, which seems improbable and likely included barnstorming games. Both Seamheads.com and the Center for Negro League Baseball Research calculate a record of 32-26.48 After completing their regular schedule, the Crawfords played exhibition contests against major-league all-stars. Pittsburgh defeated Casey Stengel’s National League All-Stars, 11-2, in York, Pennsylvania.49 The next day, the All-Stars got their revenge, winning 20-8, as Hack Wilson homered twice at Greenlee Field.50

Greenlee’s baseball operations lost between $15,000 and $16,000 in 1932, most likely because of construction costs, generous salaries for his players relative to other franchises, and ticket sales reported at only 69,229.51 Football, boxing, and soccer accounted for an additional 50,164 patrons for a total attendance of 119,384 from April 1932 to April 1933.52 Clark blamed the Depression and miserable conditions for spectators as a partial explanation for modest fan support at games. He contended that attendance dwindled in June as the summer turned hot because of the cost-cutting measure of leaving the grandstand uncovered. Clark also asserted that the black community grew disenchanted with practically every stadium job – concessions, groundskeeping, ticket sales, etc. – going to whites, who lived outside of the neighborhood.53

Greenlee remained undeterred in his efforts to promote baseball in the Hill District. In 1933 he formed a new Negro National League and installed himself as president.54 Meanwhile, his club, which already included a star-studded lineup of Paige, Gibson, Charleston, and Judy Johnson, added fleet-footed outfielder, Cool Papa Bell.55 Bell loved playing on the Crawfords’ home field and later recalled, “[i]t was beautiful. It had lots of grass and you almost felt like you were playing in a major league park. … The best thing for me was the outfield. It gave me lots of room to run.”56 Depending on the source, the Crawfords finished 1933 either with a record of 40-21, tied for first with the Chicago American Giants,57 or 38-17 and a second-place finish behind Chicago.58 After winning a playoff series against the Nashville Elite Giants, instead of playing Chicago, Greenlee exercised his league office power and declared the Crawfords pennant winners.59

Greenlee’s presidency of the NNL irritated other owners, who called for a commissioner to be appointed because of Greenlee’s obvious conflict of interest.60 Posey’s Grays left the league in the middle of the 1933 campaign. Posey claimed he did so voluntarily because Greenlee demanded that owners share 5 percent of gate receipts with the league.61 However, Clark claimed the Grays withdrew from the league before members could vote on his franchise’s expulsion for signing players already under contract with the Detroit Stars.62

Prohibition officially ended on December 5, 1933, which was surely damaging to Greenlee’s criminal empire. However, as Clark reported, Greenlee had a contingency plan and mitigated his losses. His nearby Crawford Grill was the first local establishment with an alcohol license. The Grill was quickly “jammed and packed [with customers] – buying – the hard stuff at 15 cents per drink and high-test beer at 10 cents a glass.”63

In the spring of 1934, Greenlee Field’s grandstand remained uncovered, which left the structure unfinished. To the stockholders of the Bedford Land Company, Greenlee proposed adding an awning-style roof, but they declined his request.64 On the field, the Crawfords were 47-27, but finished second in the NNL behind the Philadelphia Stars.65 The Crawfords played a home schedule of 25 games.66 Even the rival Grays occasionally played home games there.67 Once again Paige provided the highlight of the Crawfords’ season. On July 4 he struck out 17 Grays as he threw his second no-hitter at Greenlee Field.68 This time Gibson was his catcher in the 4-0 victory over Homestead before a reported audience of 10,000.69

Paige was one of the most popular Crawfords. Throughout the spring of 1935, area newspapers published accounts of his whereabouts and were hopeful about his return to the Crawfords.70 However, because of a contract dispute he never reported; he pitched in Bismarck, North Dakota, for the semiprofessional Churchills. Even without its star pitcher, Pittsburgh dominated the first half of the NNL and cruised to a record of 50-23, or 42-15, depending on the source.71

Pittsburgh then faced the second-half champion, the New York Cubans, in the NNL championship series. Oscar Charleston’s Crawfords defeated Martin Dihigo’s Cubans in an exciting seven-game series, taking the finale 8-7.72 Two series games were played at Greenlee Field. On September 18, Dihigo threw a complete game and the Cubans won Game Four easily, 6-1.73 The victory gave New York a three-games-to-one advantage in the series. With the Crawfords facing elimination, Bell began the comeback in Game Five by scoring the winning run on an errant throw in the ninth inning by Frank Blake, as Pittsburgh won, 3-2.74

After a summer as a baseball expatriate, Paige returned to the Crawfords in April 1936.75 Greenlee had not given up on putting a roof over his grandstand. However, with uncooperative stockholders unwilling to underwrite the project, he needed to find another way to raise money.

To increase revenues, he offered season tickets. According to the Pittsburgh Courier, “[t]he season pass answers a demand by fans since the club was organized in 1932 and will sell for $8.00, admit the holder to a grandstand seat to any game played at Greenlee Field by the Crawfords, whether opposed by a league or independent club.”76 In addition, during the first half, Greenlee promoted a drawing for a 1936 Ford sedan with the winning ticket to be announced on July 4.77 The Crawfords swept an Independence Day doubleheader from Homestead; the Pittsburgh Courier did not report who won the car.78 The promotions failed to raise the funds needed to cover Greenlee Field’s grandstand. Years later, Buck Leonard always recalled fans broiling in the hot afternoon sun at the park.79

With a record of 48-33, the Crawfords again raced to the stop of the NNL standings.80 They were scheduled to face the Washington Elite Giants in a playoff series at Nashville’s Sulphur Dell.81 On September 28, 1936, the Tennessean reported the series was tied at one game apiece.82 For reasons that remain unclear, the owners aborted the series; the Center for Negro League Baseball Research has concluded that “the Pittsburgh Crawfords clearly had the best team over the course of the entire season.”83 Nonetheless, Gus Greenlee’s fortunes soon took a downward turn.

In March 1937 Greenlee had financial setbacks in his numbers business.84 Because he needed money, he dealt Gibson and Johnson to Posey’s Grays for Lloyd “Pepper” Bassett, Henry Spearman, and cash.85 Despite the trade, the Crawfords returning players should have made them competitive in the NNL. However, later that spring, Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo signed eight of the Crawfords to big contracts. Paige, Bell, Leroy Matlock, Pat Patterson, Harry Williams, Sam Bankhead, Spoon Carter, and Bill Perkins jumped to Trujillo’s San Domingo Stars. An angry Gus Greenlee lodged a complaint with US State Department, which proved fruitless.86 To add insult to injury, the Stars actually played the New York Cubans in an exhibition game at Greenlee Field that September.87 Charleston, who was now 40, remained one of the few holdovers; however, Pittsburgh sank to a distant sixth in the NNL with a record of 18-35.88

The following spring, in an apparent cost-cutting measure, the Crawfords stayed in Pittsburgh for spring training.89 They improved their record to 22-21 and finished in fourth place in the NNL.90 However, the summer of 1938 held no reprieve for Greenlee or his ballpark. On July 23, the Pittsburgh Courier reported that the Federal Housing Administration had allocated money to construct three housing projects in Pittsburgh. The Pittsburgh Housing Authority selected Greenlee Field as the site for one project and offered $50,000 for the property.91 The news story suggested that if the stockholders turned down the sale, the Housing Authority would take the parcel by eminent domain.92

Clark reported that the Authority actually offered $60,000 as its opening bid, but it eventually paid the shareholders only $38,000 for the property.93 That fall, the Authority began making payments for properties in the Hill district to construct “Bedford Dwellings.”94 The Crawfords played their final game at Greenlee Field on September 3, 1938, against the Grays.95 Although a box score has not been located, one week later, the Courier mentioned that the Grays had beaten the Crawfords 13 straight times.96 The last sporting contests at the field appear to have been a softball game between boxer Joe Louis’s Detroit Brown Bombers and local all-stars,97 and a soccer tournament.98

Wendell Smith lamented the end of the brief era, writing, “Greenlee Field, home of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, once the best Negro League ball park in the country, looks like a graveyard now.”99 Soon after his summation, classified advertisements for Greenlee’s lights and steel beams appeared in the Pittsburgh Press.100 Workers officially began tearing down the grandstand and the offices in December.101 Although Posey expressed some sadness at losing Greenlee Field, he candidly admitted it had “been a financial stumbling block in the path of the Grays since 1932.”102

In February 1939 Greenlee skipped the annual winter meeting of the NNL; the members treated his absence as a resignation of his presidency.103 Later that spring, he also resigned as the president of the Crawfords.104 In his letter to the board, he cited the loss of his ballpark as a tipping point in his decision:

“Greenlee Field has passed into history, and we have no home grounds that we can control. We can no longer plan for the day when improved industrial conditions will appear and make more profitable athletic activity in this section – from which activity our own organization would share in these profits. The stinted support given to Greenlee Field when it was considered one of the best diamonds in the organized circuit, is taken as an indication by me that a positive loss must be arranged for in Pittsburgh this year.”105

Greenlee sold the franchise to Hank Rigney, who moved the Crawfords to Toledo, Ohio, where the club switched to the Negro American League in 1939.106 After moving to Indianapolis the next year, the Crawfords wound up their operations after the 1940 NAL season. Greenlee died on July 7, 1952. In his obituary, the Pittsburgh Courier cited his ballpark as marking the beginning of “an era of diamond lore which eventually gave Negro players recognition in white organized baseball.”107

In his epitaph for the park, John Clark documented Greenlee’s financial losses in providing a venue that black fans could proudly call their own. In an oft-cited passage, he bitterly closed: “Greenlee Field joins the list of banks, industries and other enterprises which should not be again attempted in this city for the next 100 years.”108

On July 17, 2009, the State of Pennsylvania unveiled a historical marker in the Hill District forever memorializing the ballpark’s place in the history of the Negro Leagues and Pittsburgh.109 Thanks to Geri Strecker’s meticulous research, the marker was properly located “directly where Greenlee Field’s arched entry gates had been.”110 The marker reads:

GREENLEE FIELD

“Located here from 1932 to 1938, this was the first African American owned stadium in the Negro Leagues. Home of Gus Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords baseball team, 1935 Negro League champs. Players included Hall of Famers Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and Cool Papa Bell.”

There has been debate over where Greenlee Field fits within the realm of baseball parks built for black clubs, and whether it really was the first of its kind. In “A Historical Look at the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Impact on Black Baseball on American Society,” Richard L. Gilmore Jr. cites the Hill District’s Central Park as an earlier example.111 According to baseball historian Gary Ashwill, Tate Field in Cleveland was a black-owned ballpark that predated Greenlee Field.112 Ashwill argues that Greenlee’s ballpark was actually the final attempt at true autonomy by a Negro league owner, writing:

“It also strikes me that Greenlee Field is misunderstood if it’s thought to be a pioneering enterprise, the ‘first’ of anything. In fact the Crawfords’ ballpark was actually a backwards-looking enterprise, an attempted revival of the golden age of the Negro leagues in the 1920s. With the collapse of Rube Foster’s NNL and the Eastern Colored League, black teams in the 1930s turned more and more to barnstorming, and instead of building their own parks they rented major and minor league venues. Greenlee Field was not the first of its kind, but the last. Its demolition in 1938 marked the end of a particular dream of black self-sufficiency, and served as a harbinger of the age of integration that was to follow.”113

By 1955, as the Negro leagues were winding down, columnist Marion Jackson opined that “[t]he decline of Negro baseball is due to the failure of clubs to own their ball parks.”114 Thus, Greenlee Field should not just be remembered as the home of arguably the most successful team in the history of black baseball, but also within a much broader historical context of independent black-owned businesses.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes thank Cassidy Lent, a reference librarian at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, who provided him with Geri Strecker’s excellent article on the history of Greenlee Field. Strecker’s research was so exhaustive that the author resisted the temptation to read the article until the first draft of this chapter was complete. Longtime SABR member William J. Plott was helpful in discussing Marion Jackson’s 1955 column about the decline of the Negro leagues. Finally, the author is grateful to members of the Historical Negro League Baseball Site on Facebook, who helped to identify other baseball parks that were owned by Negro league clubs.

Notes

1 phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/documents/1865-1945/great-depression.html.

2 Mark Whitaker, Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 91; Brian McKenna, “Gus Greenlee,” SABR BioProject: sabr.org/bioproj/person/fabd8400.

3 Jeremy Beer, Oscar Charleston: The Life and Legend of Baseball’s Greatest Forgotten Player (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 225; John N. Ingham and Lynne B. Feldman, African-American Business Leaders: A Biographical Dictionary (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press 1994), 297.

4 Monte Irvin, Few and Chosen Negro Leagues: Defining Negro Leagues Greatness (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2007), 172; Leslie A. Heaphy, The Negro Leagues: 1869-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003), 103.

5 Whitaker, 94; McKenna.

6 Whitaker, 99-100; Heaphy, 228; Brian Carroll, “To Pittsburgh from Chicago: A Changing of the Guard in Black Baseball and the Black Press in the 1930s,” Black Ball, Vol 2. No. 2, 2009: 92.

7 Lewis Dial, “The Sports Dial,” New York Age, September 3, 1932: 6.

8 Whitaker, 97.

9 Dial, 6; Whitaker, 99; Richard L. Gilmore Jr., “A Historical Look at the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Impact of Black Baseball on American Society,” The Sloping Halls Review, 1996: 67.

10 Gilmore, 67.

11 Dial, 6.

12 John L. Clark, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 10, 1938: 17; Phil Dixon, The Negro Baseball Leagues: A Photographic History (New York: Amereon Ltd. 1992), 156. Chris Fullerton’s book, Every Other Sunday (Birmingham, Alabama: R. Boozer Press, 1999), 67-68, delves into the issue of the availability of Rickwood Field for the Birmingham Black Barons, when the Birmingham Barons (the primary tenant) were on the road. Without their own ballpark, the Black Barons traveled so much, they rarely played games in Birmingham. Fullerton, 65.

13 Dixon, 156; Geri Strecker, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field: Biography of a Ballpark,” Black Ball, Vol. 2, Number 2, Fall 2009: 37-67.

14 Clark, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field,” 17.

15 William G. Nunn, “Sport Talks,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 26, 1931: 14.

16 Nunn, “Sport Talks.”

17 Strecker: 40.

18 Paul A.R. Kurtz, “Crawfords, Black Yanks Vie Tonight,” Pittsburgh Press, April 29, 1932: 41; Clark, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field”: 17.

19 “Crawfords Cut Prices for All Baseball Games,” Chicago Defender, July 16, 1932: 8. Getting to the ballpark was also economical for fans who were not within walking distance. On November 19, 1932, the Pittsburgh Courier published a public service article entitled, “How to Reach the Greenlee Field With Only One Car Token.”

20 “Oscar Charleston to Lead Crawford Club this Year,” Pittsburgh Press, February 14, 1932: 18.

21 “Gus Greenlee and the Crawfords,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 11, 2006: C-7.

22 Clark, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field”: 17; Jennifer Kaye, “Let’s Learn from the Past (Greenlee Field),” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 15, 2007: 53; McKenna.

23 “Gleanings from Greenlee Field,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 11, 1932: A4.

24 “Ticket Rush On for Pittsburgh Grid Classic,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 19, 1932: 1. The Pittsburgh Pirates professional football team, who were later renamed the Rooneys and finally the Steelers, used Greenlee Field for workouts. “Local Pros Drill for Cincinnati Fray,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, October 6, 1933: 43; “Pro Eleven Faces Cuts, Says Coach,” Pittsburgh Press, August 23, 1936: 20.

25 John L. Clark, “Wylie Avenue,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 9, 1933: 2.

26 The wall, and other aspects of Greenlee Field can be seen by searching the Charles “Teenie” Harris collection at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art. collection.cmoa.org/.

27 “Oscar Charleston to Lead Crawford Club This Year,” Pittsburgh Press, February 14, 1932: 18.

28 Clark, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field”: 17; Art Rust Jr., “Walter ‘Buck’ Leonard: Fence buster: Black League’s Lou Gehrig,” New York Amsterdam News, May 26, 1979: 72.

29 “Oscar Charleston to Lead Crawford Club this Year.”

30 Strecker: 37-62.

31 Strecker: 47.

32 Strecker: 44. Strecker discovered in her research that “[t]he facade used locally kilned red brick with simple corbelling along the top of the two-story section and along the lower section between the arched entrances and the two exit gates.” Strecker, 47. However, no source has confirmed whether Greenlee and the Bedford Land Company utilized bricks from the now defunct Entress Brick Company, but this would have been a local decision, which would have saved material costs.

33 “Crawfords Work Out at Hot Spring[sic],” Pittsburgh Courier, March 19, 1932: 15; John L. Clark, “I Believe You Should Know: Following the Crawfords,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 9, 1932: 14; “Crawfords Back, Set for Test,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 30, 1932: 15.

34 “Plan Dance to Honor Crawfords,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 9, 1932: 15; “Crawfords Reception Next Week,” April 23, 1932: 5; “Crawford Club Opens Tonight,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 29, 1932.

35 “Crawford Club Opens Tonight”; Paul A.R. Kurtz, “Carl Jordan to Play with Geisler Nine,” Pittsburgh Press, April 28, 1932: 27.

36 Chester L. Washington, “Sportively Speaking,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 7, 1932: 15.

37 “Expect Record Crowd at Park,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 30, 1932: 15.

38 “Hubbard Pitches Three-Hit Game to Beat Page, 1 to 0,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 7, 1932: 15. According to Strecker, Gibson was “recovering from an appendicitis operation he had undergone in Hot Springs.” Strecker, 54.

39 “Crawfords Defeated in Opening Game,” Pittsburgh Press, April 30, 1932: 9.

40 It is unclear whether Dave Thomas or Clint Thomas delivered the winning hit for New York. Both played for the Black Yankees in 1932, but only one “Thomas” appeared in the box score for the opener. Bankes cited Clint Thomas with making the final catch in center, so it appears he also got the winning hit. Jim Bankes, Pittsburgh Crawfords (North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2001), 24.

41 “Hubbard Pitches Three-Hit Game.”

42 “Hubbard Pitches Three-Hit Game.”

43 “New York Yanks Win Series from Crawfords,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 16, 1932: A5; “Paige Twirls No-Hit Win Over Black Yanks,” Chicago Defender, July 16, 1932: 8.

44 “Night Hero,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 20, 1932: A5.

45 “Greenlee Field Installs Lights,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 10, 1932: A5; Strecker: 49.

46 “Crawfords, Grays Play at Midnight,” Chicago Defender, September 10, 1932: 9; “Greenlee Field Introduces The Midnight Game,” Norfolk (Virginia) Journal and Guide, September 17, 1932: 13.

47 Al Abrams, “Sidelights on Sports, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 22, 1964: 20.

48 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/organization.php?franchID=PC; cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/East-West%20League%20(1932)%202019-10.pdf.

49 “National League Downed by Crawfords,” Evening News (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), September 28, 1932: 12.

50 “Major All-Stars Beat Crawfords by 20 to 8,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 29, 1932: 16.

51 McKenna; Dixon, 158; “Greenlee Field Preparing for Opener on May 6,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 15, 1933: A4.

52 “Greenlee Field Preparing for Opener.”

53 Clark, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field”: 17.

54 “Eastern Owners Meet New League Head, Boom Seen,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 11, 1933: 14.

55 “Craws Sign Bell, Cooper, Hunter,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 18, 1933: 15.

56 “Greenlee Field Site Earns Place in History,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 17, 2009: 31.

57 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1933&lgID=NN2.

58 cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/Negro%20National%20League%20(1920-1948)%202019-10.pdf.

59 cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/Negro%20National%20League%20(1920-1948)%202019-10.pdf.

60 “No Owner Should Be Prexy, Says Wilson,” Afro-American, August 5, 1933: 20.

61 Cum Posey, “Posey Reveals Why Grays Left Nat’l Ass’n,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 8, 1933: A4.

62 John L. Clark, “Baseball’s Future Lies in Organization,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 22, 1933: 15.

63 John L. Clark, “Wylie Avenue,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 9, 1933: 2.

64 Clark, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field,” 17. Strecker suggests that once Greenlee Field got lights the roof was no longer a necessity. Strecker, 55-54. However, most baseball games would have still be played in the daytime during this era and the roof would have also kept fans dry during rain delays.

65 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/team.php?yearID=1934&teamID=PC.

66 “Free Ford, Season Passes Offered at Greenlee Field,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 9, 1936: A4.

67 Chester L. Williams, “Grays Blast Birmingham Barons’ Victory Hopes by 9-2 Score,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 30, 1994: A5; Robert Peterson, “Josh Gibson Was the Equal of Babe Ruth, But …,” New York Times, April 11, 1971: SM12. By 1938 Greenlee Field presented Cum Posey with a Hobson’s choice. Fans of the Grays did not attend games at Greenlee Field. However, he also did not want to alienate residents “who honestly believe that the Grays should play all of their homes games at Greenlee Field because of the money put in it by colored investment.” Posey’s curious solution to the dilemma was to play home games outside of Pittsburgh. “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 4, 1938: 17.

68 William G. Nunn, “Paige Hurls No-Hit Classic,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 7, 1934: 1.

69 William G. Nunn, “Paige Hurls No-Hit Classic.” By 1954, the reported attendance for the game had grown to 13,000. “Sports Slice,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 16, 1954: 15. Paige’s teammate Harold Tinker later remembered, “when Satchel pitched, there was nowhere to put all the people anyway.” Clara Herron, “Lost Pittsburgh,” Pittsburgh-Post Gazette, December 25, 1990: 35.

70 “Pirates Beat Semi-Pro Team in First, 3 To 1,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 11, 1935, 15; “Cum Posey’s Pointed Paragraphs,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 4, 1935: 14; “Cubans Meet Crawfords,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, May 11, 1935: 9.

71 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1935&lgID=NN2&tab=standings; cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/Negro%20National%20League%20(1920-1948)%202019-10.pdf.

72 “Crawfords Snare Negro Loop Crown,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 22, 1935: 44; “Crawfords Take 4 to 7, to Top Stars,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 26, 1935: 10; “Grid Circus Now in Town,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 28, 1935: 14; “Thousands See Defeat of Cubans and Stars,” New York Amsterdam News, September 28, 1935: 12.

73 “Cubans Defeat Crawfords Again,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 19, 1935: 18.

74 “Crawfords Beat Cubans by 3 To 2,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 20, 1935: 18.

75 “Satchell Paige Returns to Crawfords,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 25, 1936: A4; Chester L. Washington, “Satchell’s Back in Town,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 9, 1936: 14.

76 “Free Ford, Season Passes Offered at Greenlee Field.”

77 “Free Ford, Season Passes Offered at Greenlee Field.”

78 “Crawfords Take Two from the Grays,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 5, 1936: 16.

79 “A.J. Carr, “At Age of 40, Leonard Belted 42 Homers,” The Sporting News, March 4, 1972: 24; Art Rust Jr., “Walter ‘Buck’ Leonard: Fence Buster: Black League’s Lou Gehrig,” New Amsterdam News, May 26, 1979: 72.

80 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1936&lgID=NN2.

81 “Negro Club Will Play Pittsburgh,” Tennessean (Nashville), September 23, 1936: 10; “Elite Giants Slight Favorite to Defeat Crawfords,” Tennessean, September 27, 1936: 9.

82 “Crawford Split Two with Giants,” Tennessean, September 28, 1936: 8.

83 cnlbr.org/Portals/0/RL/Negro%20League%20Play-Off%20Series%20(1930-1939).pdf.

84 Robert Peterson, “Josh Gibson Was the Equal of Babe Ruth, But …”

85 “Grays, Crawfords in Player Trade,” Pittsburgh-Sun Telegraph, March 24, 1937: 26.

86 Richard J. Lamb, “Gus ‘Whereas-es’ Diplomats into Action Over Foreign ‘Raid’ on Negro Ball Team,” Pittsburgh Press, June 20, 1937: 2.

87 “Former Crawford Stars Play Here,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 4, 1937: 10.

88 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1937&lgID=NN2.

89 “Crawford Nine Trains Here,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, April 7, 1938.

90 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1938.

91 “Greenlee Field,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 23, 1938: 6.

92 “Greenlee Field.”

93 Clark, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field”: 17.

94 “Hill District Dweller Paid $2,000 in Slum Cleanup,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 9, 1938: 36; “City’s Housing Fund Total Now Close to $18,500,000,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, October 10, 1938: 8.

95 “Craws Battle Grays in Holiday Series,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 3, 1938: 17.

96 Wendell Smith, “Smitty’s Sport Spurts,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 10, 1938: 17. Strecker cited September 3 as the date of the final scheduled home game but reached no conclusions as to who won. Strecker: 61-62. To further complicate the issue, the following spring a columnist wrote, “in the final series with the Homestead Greys [sic], the Crawfords won four out of five.” Jerry Liska (Associated Press), “Press Passes,” Fremont (Ohio) News-Messenger, April 28, 1939: 12.

97 “All-Star Mushball Tryouts Arranged,” Pittsburgh Press, September 5, 1938: 14.

98 Harry Fairfield, “Keystone League Teams Collide Today at Greenlee,” Pittsburgh Press, October 30, 1938: 23.

99 Smith.

100 “Dismantling Greenlee Baseball Field” (Lights), Pittsburgh Press, November 20, 1938: 50; “Dismantling Greenlee Baseball Field” (Steel Beams), Pittsburgh Press, December 4, 1938: 31.

101 Clark, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field”: 17.

102 Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 10, 1938: 17.

103 “Baseball League to Be Headed By Wilson; Gus Greenlee Absent,” New York Age, February 15, 1939: 8.

104 “Crawfords’ President Resigns,” Chicago Defender, April 8, 1939: 8; “Future of Craws Still in Doubt,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 8, 1939: 17.

105 “Crawfords’ President Resigns.”

106 Heaphy, 89.

107 William G. Nunn Sr., “Sports, Political Figure Dies Quietly at Home,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 12, 1952: 1.

108 Clark, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field”: 17 (quoted in Whitaker, 121); Rob Ruck, Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 164.

109 “Greenlee Field Remembered,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 18, 2009: 10.

110 Strecker: 67 n. 83.

111 Gilmore: 67-68.

112 Gary Ashwill, “Louis Bellinger and Central Baseball Park,” February 26, 2012, accessed at agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/greenlee-field/.

113 Ashwill.

114 Marion Jackson, “Black Barons, K.C. Monarchs Owned by Tom Baird, Sid Lyne,” Alabama Tribune (Montgomery), April 22, 1955: 6; William J. Plott, Black Baseball’s Last Team Standing: The Birmingham Black Barons, 1919-1962 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2019), 232.