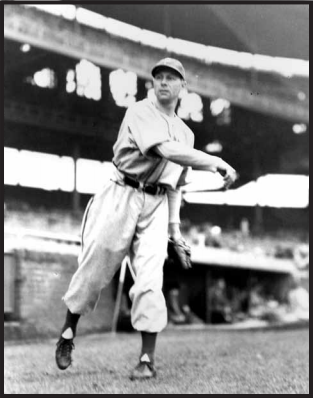

Xavier Rescigno

During the 21st century, there have been five major-league players with the first name Xavier: Xavier Nady, Xavier Paul, Xavier Cedeno, Xavier Avery, and Xavier Scruggs. In the 125 seasons of major-league baseball before that, only one other player had the unique first name, derived from that of St. Francis Xavier. (Xavier means new house or home.) The original Xavier in the major leagues was Xavier Rescigno, a Pittsburgh Pirates relief pitcher during the 1940s.

Rescigno was born on October 13, 1912, in New York City to Frederick Rescigno, an Italian immigrant who owned a butcher shop in the city, and Anna Rescigno, who was of Austrian descent. He was a star pitcher at St. Ann’s Academy (later renamed Archbishop Molloy High School). He began as a catcher, but was sent to the mound to relieve a pitcher who was being hit hard. Rescigno struck out 18 that afternoon and was the key player in two Catholic High School AAA championships won by St. Ann’s.

The right-handed hurler received a scholarship to Manhattan College, where he was a star pitcher from 1932 to 1935. He was a particular nemesis to the best college baseball squad in the city, New York University. In 1933 he stopped NYU’s eight-game winning streak with a three-hit shutout, fanning 12; a year later he ended a seven-game streak with a dominant 5-2 win.

After his career with the Jaspers, Rescigno was signed by Yankees scout Paul Krichell in 1935 and was sent to Akron of the Class-C Middle Atlantic League. He started off impressively, striking out 14 in an exhibition game against the House of David and then 13 against City College of New York. Rescigno was 2-4 at Akron, then 0-1 after being promoted to Binghamton of the Class-A New York-Pennsylvania League. In 1936 the Yankees returned Rescigno to Akron, where he had a 14-12 record. In 1937 he had a breakout season with the Smiths Falls Beavers in the Class-C Canadian-American League.

At Smiths Falls, a town of 7,000 in eastern Ontario, Rescigno was 16-7 with a league-best 1.56 ERA, and finished third in the vote for the best pitcher in the league. The season hadn’t started out as though it would be a special one. Rescigno opened with Norfolk of the Class-B Piedmont League, where he posted a 1-2 mark and a 7.03 ERA, and then was sent to Bloomington of the Class-B Three-I League, where he had two poor outings before the team folded and he was sent to Smiths Falls. There, his impressive curveball dominated league batters and the town itself really became important to him. “That was the best thing that happened to me,” he said later.1

The right-hander earned $250 a month while there and seemed to thoroughly enjoy his off time, playing golf, swimming, and enjoying the townspeople. “The town was small and everyone knew each other. It was clean and they had quite a few get-togethers with each other. Coming from New York City, I really enjoyed the small town and its friendly atmosphere,” he said.2

The Smiths Falls team fared well with a 57-49 mark, but drew only 14,197 fans for the season and left town a year later. Rescigno fared no better in 1938, his last season in the Yankees organization. It began promisingly as he pitched three perfect innings against the Boston Red Sox in spring training, but then it went downhill. Rescigno became known as “somewhat of a problem child,” according to the Montreal Gazette.3 He started the year with the Newark Bears and went 0-1 with a 10.50 ERA in seven games. The Yankees demoted him to their Southern Association team in Chattanooga, but Rescigno refused the assignment. After a three-week suspension, he was sent to Binghamton. After pitching in nine games (0-1), he was released by the Yankees. Rescigno felt he had a good reason for refusing to go to Chattanooga; he had met his future wife, Eleanor (Curtin), while with Newark and didn’t want to leave. (They were married before the year was over.)

In 1939 Rescigno landed in the Brooklyn Dodgers organization and got his career back on track. He credited his manager at Montreal, future Hall of Famer Burleigh Grimes, with teaching him more about pitching in four weeks than he had learned in all the years before.4 He wasn’t successful with the Royals, with a 1-3 mark and an ERA over 5.00, but when the Dodgers sent him to Elmira, he rebounded with 11 wins and an ERA of 2.21.

A year later, the curveball pitcher got another opportunity with the Royals, but was once again unsuccessful, allowing seven runs in 1⅓ innings. The Dodgers sold his contract to the Albany Senators, a Pirates farm team. It was a good move for Rescigno.

Rescigno won 12 games for Albany in 1941, and was impressive pitching in the offseason for the semipro Brooklyn Bushwicks. In his first game for the Bushwicks, he faced Roy Campanella and the Baltimore Elite Giants of the Negro Leagues. (The Bushwicks were noted for both fielding and playing against multi-ethnic teams.) He pitched a four-hit shutout and held the future Hall of Fame catcher hitless in three at-bats.

Rescigno’s success in 1941 was a precursor to his best professional season, 1942. He had a phenomenal start for Albany, winning 15 of his first 18 games. (All three losses were by a single run.) By the end of August Rescigno had 20 wins and finished with a 23-6 record for the pennant-winning Senators. He had a 1.76 ERA with a league-best 0.952 WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched), and gave up just 181 hits in 251 innings. He finished second in the MVP voting and was named to the league’s all-star squad as the top right-handed pitcher.

The Pirates took notice and purchased both Rescigno and teammate Ralph Kiner in September, giving the now 29-year-old pitcher his first true opportunity to make a major-league roster in 1943. With many Pirates drafted into the military during the war, manager Frankie Frisch looked to his array of young minor-league talent to fill the spots, and one he noticed was Rescigno. “I guess this fellow Rescigno, who starred for Rip Collins at Albany as the Senators went over the tape first, is a real prospect,” Frisch said.5

The loss of talent to the armed forces left the Pirates’ pitching staff in disarray. Left-hander Ken Heintzelman left for the Army in March. Max Butcher was 1-A, and Johnny Lanning and Jack Hallett, with no children, were also at risk to be drafted. Butcher never did get called up. Lanning had been turned down by the Navy the year before due to hay fever. Hallett pitched in 1943 before heading out. Frisch still had an opening on his staff in 1943 and felt Rescigno could be a great fit, especially after impressively stopping the Indians in relief in an exhibition game.

After eight minor-league seasons, Rescigno made the Pirates Opening Day roster. It took only two games before the 30-year-old side-armer got to pitch. In a start against the Cubs in Chicago on April 22, Hank Gornicki was not sharp, allowing six hits and three runs in two innings. Rescigno replaced Gornicki in the third inning and retired the first seven batters he faced. Overall he surrendered only two hits and a walk in four shutout innings; Frisch had found an effective arm out of the bullpen.

On the 27th Rescigno pitched a perfect ninth inning of work in a victory over Cincinnati. On May 4 he got his first start, at Crosley Field against Cincinnati. He scattered 13 hits but was the quintessential bend-but-don’t-break pitcher, allowing only three Reds baserunners to score while stranding 13 in a complete-game 8-3 win, his first major-league victory.

Rescigno continued in the rotation through May, starting five games and losing three in a row, including two 11th-inning defeats to the New York Giants and Boston Braves. While 1-3, Rescigno had pitched well and had some hard luck. Before his first start at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field on May 29, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote, “‘X’ has only one game in the ‘win’ column so far this season against three losses, but his pitching had been of high caliber and should be a consistent winner if his mates will back up his mound work with some hits” 6

His mates did in fact support him in this game, pounding out 16 hits including a two-run-homer by Vince DiMaggio in a 12-4 victory over Philadelphia. Rescigno had a four-hit shutout going into the ninth inning, but two errors by the Pirates led to four runs. After a poor performance a week later in a start against the Giants, Rescigno spent the rest of the season in the bullpen, starting only one game until a stretch in August when he made four unimpressive starts.

Rescigno was more effective in September, getting his sixth victory as he shut out the Reds in a four-hit, 7-0 victory. It was a fine rookie campaign, with a 6-9 mark and a 2.98 ERA. It was also the end of Rescigno’s dual starter/relief role. He pitched mostly in relief the rest of his time with the Pirates. While Pittsburgh lost more players to the war effort in 1944, Rescigno was reclassified from 1-A to 4-F a physical at the Army’s induction center in New York City in February. He spent much of the 1944 season as the 1940s version of the team’s closer, finishing 25 of his 45 games and starting only six, four of them in the first month and a half.

Those four starts were not productive; Rescigno allowed 12 earned runs in 23⅔ innings. His ERA stood at 5.40 on May 29. He pitched better the rest of the campaign, ending with a 4.35 earned-run average and 10 victories, with the final two coming in two starts in September in which he allowed seven runs in 11 innings. Rescigno ended the campaign second in the league with 48 games pitched and by later computation had five saves. (Saves were not a statistic in that era.)

Spring training in Muncie, Indiana, in 1945 was memorable for the amount of snow that fell. In 1995, Rescigno recalled that snowy spring. “I remember once we had to shovel the snow off. It was a high school diamond so it wasn’t in good shape. We had to do the grounds keeping ourselves.”7

That spring training was a precursor to Rescigno’s final season in the major leagues. He was third in the National League in saves (9), sixth in games pitched (44) and third in games finished (27), but he allowed 95 hits in 78⅔ innings with a subpar 1.640 WHIP and a 5.72 ERA. In his only start of the season he allowed six runs on five hits in one-third of an inning during a 6-0 loss to the Giants. Rescigno had pitched well the first two months, with a 2.88 ERA as late as May 27, but fell apart after that with a horrible June and July, as he permitted 29 earned runs in 29⅓ innings, surrendering 46 hits and walking 21.

For the third consecutive September, Rescigno was effective, as his ERA for the season’s final month was 3.38, but with many of the players returning from the armed forces as World War II came to an end, plus the fact that Rescigno was now 32 years old, the side-armer’s major-league career came to an end. The Pirates sold him to their farm club in the Pacific Coast League, the Hollywood Stars, where he pitched two seasons, posting an 11-9 record in each. He missed time when he was suspended during a series against the San Diego Padres in 1946 because of an argument he had with manager Buck Fausett, but also was on the bench with a sore arm later in the ‘46 campaign. Still, the 1946 season was memorable for Rescigno as his wife gave birth to a son. The Stars presented the couple with a baby buggy and other gifts in a pregame ceremony following the birth.

After the 1947 season Rescigno was traded to the San Diego Padres of the PCL for pitcher Vernon Kennedy. The Sporting News referred to Rescigno as a “temperamental right-hander”8 because he reportedly had several arguments with his San Diego roommate, catcher Hank Camelli, a former teammate with Albany and Pittsburgh. Rescigno struggled in his two seasons with San Diego. In 1948 he was 18-14, but was out almost two weeks with a stomach ailment and had a 4.64 ERA. He had a chance to win 20 games, but failed in his final two starts, both against his former Hollywood teammates. He pitched for Ponce in the Puerto Rican League after the season, and was ejected in a loss to Caguas on November 12 for arguing with umpire Dick Powell. In 1949 Rescigno fell to 10-15 with the Padres as his earned-run average ballooned to 5.69.

Now 37 years old, Rescigno pitched in four games for the San Francisco Seals (16.50 ERA), before being sent back to the place where he had enjoyed his most success as a professional, Albany. After a 7-11 campaign in 1950, he had a rare achievement in 1951, winning four games while pitching a total of only 5⅔ innings. Rescigno said simply that “I never was as lucky in all my life.”9

Albany released Rescigno a short time later. Mr. X had a 150-118 record in the minor leagues to go with his 19-22 mark with the Pirates. He quickly found a job in baseball after his release, managing the Boston Braves’ affiliate in the Class-D Appalachian League, the Bluefield (West Virginia) Blue-Grays. The team’s 69-59 mark was good enough for a second-place finish in the six-team circuit. That was his swan song in baseball. Many years later he explained: “… Then baseball took a turn for the worse and the minor leagues went from 23 teams for each major league team down to 4 or 5 teams. We all lost our jobs and I had to go work for a living.”10

After his time in professional baseball, the mysterious Mr. X, as he was known at Manhattan, became truly mysterious. He had worked in the real-estate business in New York City during off seasons in his playing days and he settled in Ridge, New York, on Long Island, after his retirement. But other than the fact that a son named Fred Rescigno was signed to a minor-league contract by the New York Mets in 1963, not much is known about baseball’s first Xavier following his retirement from the game.11

Also, a customer review on Amazon.com of Doug Summer’s book Baseball Summer: The Story of the 1937 Smiths Falls Beavers, supposedly from Rescigno’s daughter-in-law, said, “Xavier Rescigno was my father in law. … I never met him. …this book let me peek into the past, gave me insight into that time period when my husband was little … & actually see who my husband looks like.”12

Rescigno died on December 24, 2005, in Sun City West, Arizona, at the age of 93. Earlier that year he had written to the San Diego Padres’ Xavier Nady congratulating the newest member of the Xavier club on joining the elite fraternity. He also had met Nady before a game in San Diego. Meeting the original Xavier delighted Nady, who said, “It was really cool, one Xavier to another. How often do you see that?”13

Sources

The Afro American

BaseballAlmanac.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-reference.com

Archbishop Molloy High School web site

Charleston Gazette

The Daily Times

Montreal Gazette

New York Times

Phillips, Doug, Baseball Summer: The Story of the 1937 Smiths Falls Beavers (Raleigh, North Carolina: Lulu Publishing, 2013).

ProStanners.com

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Pittsburgh Press

The Sporting News

Notes

1 Doug Phillips, Baseball Summer: The Story of the 1937 Smiths Falls Beavers (Raleigh, North Carolina: Lulu Publishing, 2008), 152.

2 Ibid.

3 “Rescigno, Ex-Newark Pitcher, Bought by Royals on Approval,” Montreal Gazette, February 22, 1939, 15.

4 Mark T. McNeal, “Casual Close-Ups,” Montreal Gazette, April 17, 1939, 17.

5 Charles J. Doyle, “Frisch Sees Buccos In On Free-For-All,” The Sporting News, December 3, 1942, 19.

6 Dick Fortune, “Former Nat Makes Good on New Job,” Pittsburgh Press, May 29, 1943, 7.

7 Bob Fulton, “The Strangest Spring Training There Ever Was,” Indiana Gazette, March 3, 1995, 14.

8 “San Diego,” The Sporting News, May 5, 1948, 22.

9 Charley Young, “Mr. X Hurls Less Than Six Innings to Tab Four Wins,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1951, 32.

10 Baseball Summer, 152-153.

11 Fred Rescigno’s signing is reported in the Reading Eagle of September 22, 1963.

12 Amazon.com website, amazon.com/Baseball-Summer-Story-Smiths-Beavers/dp/0557016908/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1408827629&sr=8-1&keywords=smiths+falls+beavers

13 Ben Shpigel, “Xavier is a Household Name. At Least it is in the Nady Household,” New York Times.com, March 21, 2006.

Full Name

Xavier Frederick Rescigno http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695

Born

October 13, 1912 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

December 24, 2005 at Sun City West, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.