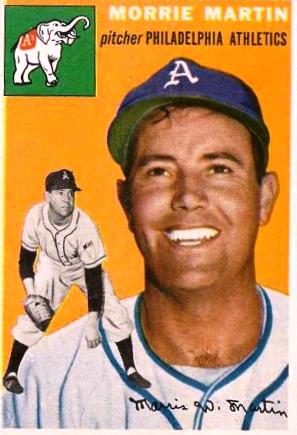

Morrie Martin

Morrie Martin’s initials are famous. Mickey Mantle is better known than the six-foot-tall left-handed pitcher who pitched with seven different major league teams in a career that started in 1949 and ended in 1959. Mickey Mantle as a hitter produced statistics that made him a first ballot Hall of Famer. Morrie Martin as a pitcher produced statistics that could have ended his major league career before 1959. In 604 2/3 innings over a span of 250 major league games, Martin walked more batters (252) than he struck out (245). Few pitchers whose walks exceed their strikeouts are able to survive very long in the major leagues. Somehow Martin did in a big league career that saw him win more games (38) than he lost (34), despite pitching two-plus seasons for very bad Philadelphia A’s teams. Martin accomplished more in his baseball career than his statistics would predict.

Morrie Martin’s initials are famous. Mickey Mantle is better known than the six-foot-tall left-handed pitcher who pitched with seven different major league teams in a career that started in 1949 and ended in 1959. Mickey Mantle as a hitter produced statistics that made him a first ballot Hall of Famer. Morrie Martin as a pitcher produced statistics that could have ended his major league career before 1959. In 604 2/3 innings over a span of 250 major league games, Martin walked more batters (252) than he struck out (245). Few pitchers whose walks exceed their strikeouts are able to survive very long in the major leagues. Somehow Martin did in a big league career that saw him win more games (38) than he lost (34), despite pitching two-plus seasons for very bad Philadelphia A’s teams. Martin accomplished more in his baseball career than his statistics would predict.

Off the baseball diamond, Morrie’s accomplishments were far greater. He survived combat during World War II at Normandy Beach, the Battle of the Bulge, and Remagen Bridge. Morrie was a combat engineer in World War II, which meant that he was building things on the front lines that the enemy did not want built. Twice during the war he was hit by enemy fire. For his service in World War II, he was awarded two Purple Hearts, four battle stars, and an Oak Leaf Cluster.

Morrie Martin was the fourth of seven children born to Levi and Minnie Martin. He was born on September 3, 1922, near Dixon, Missouri. Times were tough for the Martin family even before the Great Depression hit. The family moved several times during Morrie’s childhood. His dad worked primarily as a carpenter and farm hand in a variety of places for not much pay. When he was a child, Morrie became proficient at throwing rocks at wild rabbits in the fields near his home. The rabbits he hit ended up on the family dinner table. Also as a child, he liked to fish, using grasshoppers for bait. Any fish he caught also ended up on the family dinner table. Throughout his life Morrie remained an avid hunter and fisherman.

Martin’s formal education ended at the eighth grade. At that time his older brother Bill was working for the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps. At the age of fifteen Morrie, who lied about his age to get into the program, joined his brother in working for the CCC. Morrie’s work in construction projects for the CCC foreshadowed his later service during World War II with the combat engineers. About that time Morrie also began playing baseball for town teams in central Missouri.

Wally Schang, a catcher World Champion Athletics of 1913, is the only major leaguer buried in Dixon, Missouri. Coincidentally, Morrie Martin is the only major leaguer who was born there. In 1940, well after Schang’s big league career ended, the ex-catcher saw Morrie pitch in Rolla, Missouri, for the Dixon town team. Impressed by what he saw, Schang referred Martin to the front office of the Chicago White Sox. In 1941 the White Sox invited the young man to a tryout in Leesburg, Florida. Morrie was signed to a contract after his tryout and sent to Grand Forks, North Dakota, the White Sox’ affiliate in the Northern League. The eighteen-year- old Martin had a terrific season. He pitched 193 innings for Grand Forks in 1941, winning 16 and losing 7, with a league-leading ERA of 2.05. His 16 wins in 1941 were the most he would achieve in a season during his seventeen-year professional career.

As Martin was beginning his baseball career, war was raging across Europe and the Pacific Ocean. In response to the deteriorating international situation, in 1940 the United States instituted its first peacetime military draft. The 1940 Selective Service Act required men between the ages of 21 and 35 to register for military service. Martin was exempt from the draft during his first season of professional baseball in 1941. After Pearl Harbor the age brackets for the draft were changed to require men between the ages of 18 to 45 to register.

Morrie pitched one more year in the minor leagues before he was inducted into the army on January 2, 1943. The White Sox assigned him to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association for the 1942 season. He pitched only 71 innings for the Saints in 1942, 122 fewer innings than he pitched in his first year of professional baseball. In his last baseball season before entering the army, he had a 1-4 record and a 4.69 ERA.

Martin didn’t pick up a baseball from the time he left the United States for service in World War II until he returned home in 1945 to recover from his war injuries. He was assigned to the First Army’s 49th Combat Engineers after he was drafted. He was part of “Operation Torch” in North Africa in 1943; later, on June 6, 1944, he was part of the D-Day landing on the beaches of Normandy. Shortly after the D-Day landing, he was hit by shrapnel in his neck, left hand and arm while on guard duty near St. Lo, France. He stayed on the front lines despite his injuries. Late in 1944, he was involved in the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes Mountains of Belgium. Martin suffered frostbite in the bitterly cold temperatures of the Ardennes Mountains, but he remained with his unit until he was seriously injured in combat in 1945.

On March 23, 1945, at a crossroad near Bonn, Germany, Morrie was shot in the leg. The wound nearly cost him his leg. Evacuated to a hospital in Saint-Quentin, France, he was fortunate to come under the care of a nurse who looked at his chart and discovered he was a baseball player. The nurse recommended that he resist the recommended amputation of his leg and try to halt his infection with penicillin. He took her advice and began a slow recovery that saved his leg and his baseball career.

Martin spent two months in a hospital in Paris before he was sent back to Fort Dix, New Jersey. He went from Fort Dix to Camp Carson, Colorado, where he was given a furlough at the end of September of 1945. While on furlough, Morrie met his future wife, Leona, whom he married in 1946. He was discharged from the army in October 1945 with two legs that were intact thanks to a nurse in France and the power of penicillin, a pitching hand that had been hit by shrapnel, and battle scars beyond those that were visible on his body.

Morrie Martin returned to baseball in 1946 with the Brooklyn Dodgers organization. Being a minor league player with the Dodgers was both a blessing and a curse. Branch Rickey, who invented the baseball farm system when he was with the St. Louis Cardinals, was in charge of the Dodgers after the war. Rickey, as was the case when he ran the Cardinals, built a large farm system for the parent club. The extensive farm system gave returning World War II vets like Martin an opportunity to play. The down side was that there was fierce competition among the large number of Dodger minor league players for the few openings on the major league roster.

Martin pitched in 25 games in 1946 for the Ashville (North Carolina) Tourists of in the class B Tri State League. He compiled a 14-6 record, with a 2.71 ERA in 173 innings. His fine showing in 1946 kept him in professional baseball. In 1947 he pitched for Danville, a class B team in the Three I League, and for St. Paul in the American Association. In seven games for Danville, he went 3-1 with a 2.20 ERA in 41 innings. St. Paul was familiar territory for Morrie, who’d pitched there in 1942. As a 24-year-old in 1947, he went 2-3 for St. Paul, with a 4.12 ERA in 59 innings. He pitched a full season at St. Paul in 1948, compiling a 13-11 record and a 4.16 ERA in 186 innings.

Morrie Martin made his first major league appearance on April 25, 1949, in a start for the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field against the defending National League champion Boston Braves. He pitched what today would be called a quality start, giving up three runs in seven innings. Unfortunately, his mound opponent for the Braves, Bill Voiselle, pitched a six-hit shutout to beat Morrie and the Dodgers 4-0. One of the six hits Voiselle surrendered was Morrie’s first major league hit, a single in one of his two plate appearances.

On May 5, 1949, Martin got his first major league win. He entered the game in relief in the fifth inning with the Dodgers trailing the Cincinnati Reds 3-0. In the sixth inning the Dodgers scored four runs to take the lead, but the Reds went ahead again thanks to a two-run home run by Virgil Stallcup in the eighth. The Dodgers, however, answered with three runs in the bottom of the eighth to give Morrie a two-run cushion going to the top of the ninth. Morrie pitched a scoreless ninth to pick up his first big league victory, and the only win of his Dodgers’ career.

Martin pitched 30 2/3 innings in ten appearances for the Dodgers in 1949. For the year he was 1-3, with a 7.04 ERA. His ERA took a pounding in his last major league appearance for the Dodgers. On July 3 Brooklyn manager Burt Shotten called Morrie into a game at the Polo Grounds against the Giants in the sixth inning with the Dodgers trailing 7-0. When he left the game in the ninth inning, the Dodgers were trailing 16-0. In 1 2/3 innings, Morrie gave up 9 earned runs, 8 hits, and 2 walks.

After that drubbing, Morrie was sent back to St. Paul to finish the 1949 season. In 79 innings for St Paul in 1949, he had a 3-6 record with a 3.87 ERA. He returned for his last year in the Dodger organization in 1950. In his final season with St. Paul, Martin pitched in 31 games, 28 of them as a starter, and was 14-9 with a 3.65 ERA in a career-high 197 innings.

On November 16, 1950, Morrie was selected in the major league draft by the Philadelphia Athletics, who had lost 102 games during the 1950 season, finishing last in the American League, six games behind the seventh-place St. Louis Browns, and a full 46 games behind the pennant-winning New York Yankees.

In 1951 the A’s finished in sixth place, winning 18 more games than in 1950, thanks in part to Morrie Martin’s contributions. He pitched mostly in relief with the A’s in 1951, starting 13 games and appearing in 22 games out of the bullpen. He was 11-4, with a 3.78 ERA in 138 innings. He defeated every opposing American League team at least once during the year. On July 19 at Briggs Stadium, Morrie pitched the only shutout of his big league career, a 5-0 victory against the Detroit Tigers. His other complete game in 1951 was on August 19 against the New York Yankees, a game won by the lopsided score of 15-1.

Martin returned to the A’s in 1952, but he appeared in only five games, all as a starting pitcher. For the year he was 0-2 with a 6.39 ERA in 25 1/3 innings. His season ended abruptly on May 10, 1952, when a line drive off the bat of Mickey Vernon in the top of the fourth inning struck his left hand, fracturing his index finger. The fractured finger, on the same hand that had been hit by shrapnel in World War II, sidelined him almost exactly a full calendar year. Morrie’s first appearance after returning from his injury was outstanding: he pitched a complete-game 4-1 win over the Detroit Tigers on May 2, 1953. He made 11 starts and pitched 47 games in relief for the A’s in 1953. Highlights of his 1953 season included two victories over Satchel Paige of the St. Louis Browns, and a complete-game 2-1 win on May 20 against the Chicago White Sox. In 1953 Martin was 10-12, with a 4.43 ERA in 156 1/3 innings.

On June 11, 1954, the Philadelphia A’s traded Martin to the Chicago White Sox, the team that signed him as an amateur in 1941. The Sox used Martin primarily in relief. His only two starts for Chicago were in 1954, and he was outstanding in both of them. On July 31, Morrie tossed a complete game against his former team, the Philadelphia A’s, winning 4-1. On September 8, 1954, in a start against the Washington Senators, Morrie pitched 8 1/3 innings in a pitcher’s duel the White Sox won, 2-1. He remained with the White Sox until midway through the 1956 season. In his White Sox career, in 82 games, he was 8-7, with a 3.01 ERA in 140 1/3 innings. Morrie’s stay with the White Sox ended when the Baltimore Orioles claimed him on waivers on July 13, 1956.

Paul Richards, Martin’s manager with the White Sox in 1954, was both the manager and general manager for the Orioles in 1956. Richards used Martin sparingly out of the bullpen. In nine games with the Orioles, he faced only 29 batters in five innings of work He picked up his only Oriole win on July 18 in a game against the White Sox, in which he pitched two-thirds of an inning, facing left-handed hitters Jim Rivera and Nellie Fox. He was tagged for his only loss as an Oriole on July 25 in a game against the Tigers in which he pitched two-thirds of an inning. His longest appearance in a game for Baltimore was one inning pitched on August 1, 1956, against the Kansas City A’s. In 1956 Martin was a “lefty one-out guy” before the term was coined, though in his last appearance for the Orioles on September 19 the four batters he faced were all right-handed hitters

Martin spent most of 1957 in the minor leagues, pitching for Baltimore’s affiliate in the Pacific Coast League in Vancouver, British Columbia. He had a terrific season, going 14-4, with a league-leading 1.90 ERA, while completing 11 of the 22 games he started. In 175 2/3 innings Morrie gave up only three home runs. His fine season drew the interest of the St. Louis Cardinals, who purchased him from Baltimore on September 19.

He pitched 10 2/3 innings in four appearances for the Cardinals at the end of the 1957 season. Martin’s only start for the Cardinals, and his last start in the major leagues, was on September 28, 1957, against the Chicago Cubs. He pitched six shutout innings, and left the game leading 3-0. The Cardinal bullpen couldn’t hold the lead, so Morrie was deprived of getting what would have been his only major league decision in 1957.

Martin spent the first half of the 1958 season with the Cardinals He pitched in 17 games for the Cardinals out of the bullpen, compiling a 3-1 record and a 4.74 ERA over 24 2/3 innings. On July 2, 1958, the Cleveland Indians claimed him on waivers. In 14 games with the Indians, he was 2-0, with a 2.41 ERA in 18 2/3 innings. His last major league win was on August 31, 1957, against the Kansas City A’s. Morrie entered the game in the tenth inning with the score tied at 2-2. Minnie Minoso hit a home run in the eleventh inning to give the Indians a 3-2 lead. He retired the A’s in order in the bottom of the eleventh to pick up the victory.

The Indians traded Martin to the Chicago Cubs after the 1958 season. He pitched in only three games without a decision in 1959. In 2 1/3 innings for the Cubs, he gave up five earned runs. On April 22, 1959, in his last major league appearance, Martin surrendered three earned runs in one inning of relief.

Morrie spent the remainder of 1959 in the American Association with the Cubs’ affiliate in Fort Worth, Texas. He appeared in 40 games for Fort Worth and pitched well, posting a 2.67 ERA in 91 innings. The following year the Cubs changed their affiliation in the American Association to Houston, where Martin pitched in 33 games, posting a 3.13 ERA in 69 innings. Houston was Martin’s final stop in professional baseball. The Milwaukee Braves acquired him on February 23, 1961, but released him in April.

Martin worked in a variety of jobs in Washington, Missouri, after his baseball career ended. He also coached his grandson’s Little League baseball team. In his later years he enjoyed meeting people who were interested in his baseball career. He traveled to the Philadelphia area for several reunions sponsored by the Philadelphia A’s Historical Society. On an October day about six years before his death, he spent time discussing his playing career with visitors at the Bullpen Theater at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Although Martin enjoyed talking about his baseball career, he didn’t like to talk about his role in World War II. He took part in a conference held in New Orleans in 2008 about baseball and World War II that stirred up painful memories about his wartime experience. Shortly before his death, though, Morrie made a statement to newspaper reporter Dan O’Neill that shows he understood how important his wartime service was: “We had a job to do and we did it. I don’t have regrets about the time I missed in baseball. I’m proud of what we did. I’d do it again.”

No matter what part of his life Morrie Martin liked to remember, he lived a life worth remembering. Morrie Martin, at the age of 87, died of lung cancer on May 25, 2010, leaving behind two sisters, his wife, three of his four daughters, sixteen of his seventeen grandchildren, twenty-one great grandchildren and one great-great grandson.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Debbie Thornhill, Gabriel Schechter, Everet Marquart, Len Levy, Dick Rosen, Don Geiszler, Bill McCurdy, Tal Smith, and Jan Finkel for their assistance and willingness to help me with this article. Any errors are my responsibility.

Sources

Statistics are verified by baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org.

“A Day for Heroes,” StLtoday.com by Dan O’Neill (5/31/2010)

“Morrie Martin Takes His Place on the Stage” by Bill Swank in When Baseball Went to War, edited by Bill Nowlin & Todd Anton. (2008)

“A Memorial Day Tribute,” on Gabriel Schechter’s blog, Never Too Much Baseball, (June 1, 2010)

“A History of the LOGGY: Part One” by Steve Treder on the blog, Hardball Times (April 19, 2005).

“Baseball and the Armed Services” by Harrington Crissey Jr. in Total Baseball, edited by John Thorn and Pete Palmer (1989)

“The Farm System” by Bob Hoie in Total Baseball, edited by John Thorn and Pete Palmer (1989)

Transcribed interviews of Morrie Martin by Gabriel Schechter.

Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society website.

Emails from Morrie’s daughter, Debbie Thornhill

Full Name

Morris Webster Martin

Born

September 3, 1922 at Dixon, MO (USA)

Died

May 25, 2010 at Washington, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.