The Rise and Fall of Artificial Turf

This article was written by Mark Armour

This article was published in Dome Sweet Dome: History and Highlights from 35 Years of the Houston Astrodome

There was a time, not long ago, when many people hoped, or feared, that artificial playing surfaces would overtake natural grass in most outdoor sports facilities. The phenomenon started indoors, for good reasons, but by the 1970s every new park had to have fake turf, and even some of the old fields were ripping up God’s green grass and putting down the industrial stuff. The trend was part of a widespread belief in the middle of the 20th century that technology and chemistry could be an improvement on our natural world.

There was a time, not long ago, when many people hoped, or feared, that artificial playing surfaces would overtake natural grass in most outdoor sports facilities. The phenomenon started indoors, for good reasons, but by the 1970s every new park had to have fake turf, and even some of the old fields were ripping up God’s green grass and putting down the industrial stuff. The trend was part of a widespread belief in the middle of the 20th century that technology and chemistry could be an improvement on our natural world.

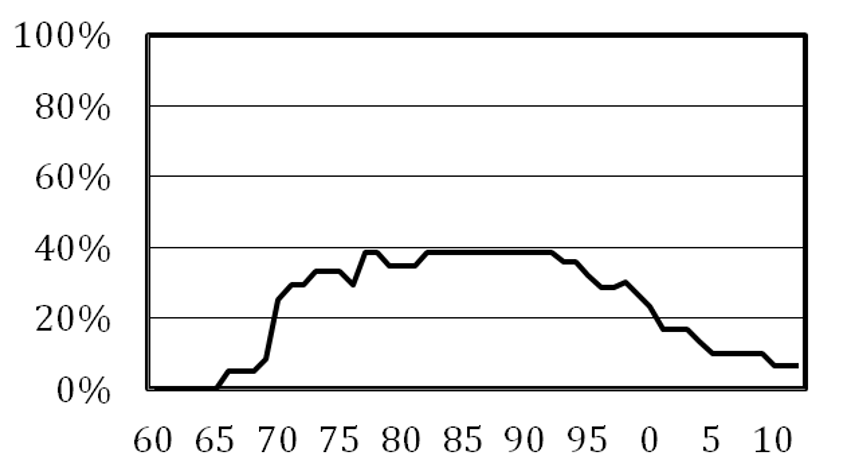

After a few short years playing baseball on artificial turf, or watching others play on it, few players or fans would admit to actually liking it, but its adoption continued for a few years more, largely in deference to football. At some point a light went on, and baseball operators decided that whatever drove them to the carpets in the first place was no longer worth it. Whereas nearly 40 percent of major-league games were played on artificial turf over a period of nearly two decades, 93 percent of all 2015 contests took place on natural grass.

Although few people weep over the demise of artificial surfaces, the game played on these fields was spectacular. The baseball of the 1970s and 1980s, whatever one might think of the uniforms, or the hairstyles, or the color of the “grass,” offered a wonderful balance of offense and defense, provided a fascinating variety of ballpark experiences (home-run parks, doubles parks, speed parks, pitchers’ parks), and gave us a dynamic group of stars, many of whom were defined by the places in which they starred – often as not, stadiums without a blade of natural grass.

It all started in Houston, Texas. The Astrodome served as the home of the Houston Astros for 35 seasons, and also housed the Oilers football team, college football and basketball, and assorted auto conventions, rodeos, and tractor pulls. The facility re-entered the news in September 2005 by serving as temporary housing for thousands of evacuees from New Orleans, victims of Hurricane Katrina. But the building’s principal sports legacy rests with two claims to fame: It was the first domed stadium, and the first professional facility to use an artificial playing surface.

The Houston club was awarded a National League franchise in 1960, and originally hoped to have its dome in place before its first game in 1962. Legal issues delayed the start of the project, which led to the construction of a temporary 32,000-seat stadium on adjacent land. In fact, the two stadiums were constructed simultaneously in sight of each other. The original Houston team was called the Colt .45s, and its temporary edifice was Colt Stadium, famous for its unbearable heat and giant mosquitoes. Few mourned the park’s demise after the 1964 season.

The opening of the Harris County Domed Stadium in 1965 was a much anticipated event, as commentators wondered whether it was possible or practical to play baseball indoors. Judge Roy Hofheinz, the team’s principal owner and the longtime champion of the dome, changed the team’s name to the Astros, and its new facility to the Astrodome, both monikers in celebration of the city’s role as the center of the thriving space industry of the 1960s.

Branch Rickey, in the last year of his life, visited the Dome and suggested that he had seen the future. On Opening Day, 24 actual astronauts threw out 24 first balls. A 475-foot-wide scoreboard displayed an elaborate light show after each Astro home run or victory, including two “cowboys” shooting guns whose bullets ricocheted around the scoreboard, leading to a series of loud explosions. The Astrodome showed American “progress” at its finest. The facility, without a single beam obstructing the view from a single seat, was soon called the “Eighth Wonder of the World.”

The field was natural grass, carefully tested to hold up under the building’s roof, which was made up of over 4,000 Lucite panels to let in nature’s sun. Unfortunately, the panels caused so much glare during practices in the spring that players had trouble catching pop flies. The solution was to paint the outside of the dome off-white, which caused the grass to die. The Astros played the last few weeks of the 1965 season on spray-painted dirt.

Hofheinz contacted Monsanto, a company that had installed “Chemgrass” in 1964 at Moses Brown School in Providence, Rhode Island, and got the firm to put its product in the Astrodome. Monsanto installed the turf in the infield in time for the Astros’ April 18, 1966, home opener, and the outfield was converted by their July 19 contest. The first man to bat on the fake grass was Dodgers shortstop Maury Wills, who singled up the middle off Robin Roberts. The players accepted the surface pretty quickly, perhaps partly because the field it was replacing was filled with holes and ruts. Monsanto changed the name of its product to “Astroturf,” a name often used for the next two decades to describe all artificial surfaces, though there were other competing technologies and brands.

Throughout the late 1960s, many journalists were predicting – and advocating – the installation of synthetic surfaces on all grass playing fields. The Sporting News, the erstwhile “Bible of Baseball” but accelerating rapidly downhill toward football primacy, favored the surfaces at least for football or multipurpose fields. Football was a major impetus for the spread of artificial surfaces, as many of the new stadiums being built in this era were multipurpose. Baseball didn’t really have a lot of pull – for the most part, the reason municipalities agreed to build new stadiums was because of football, which was booming in popularity.

The University of Houston played its home football games in the Astrodome in 1966, and many college football facilities, including those at the University of Alabama and University of Arkansas, were converted by the end of the 1960s. In 1967 Astroturf was installed at Memorial Stadium in Seattle, which hosted a pro football team, the Seattle Rangers, in the Continental League. The AFL Oilers moved over from Rice University in 1968. The Philadelphia Eagles became the first NFL convert when fake grass was installed at Franklin Field in 1969. Baseball’s All-Star Game in 1968, at the Astrodome, was billed as “Monsanto meets Ron Santo.”

The benefits touted by its early proponents were many: ease of maintenance, simpler conversion from baseball to football or vice-versa, better drainage. Football teams, even at the high-school level, would not practice on their main field for fear of tearing it up during the week – with artificial turf, there was no longer a need for practice fields. The biggest reason of all was that the surface reduced injuries. If you didn’t believe that, you only had to read the weekly half-page articles written by Monsanto for The Sporting News – or the occasional four- or eight-page spread regularly appearing in the same paper. The stories boasted of the rapid, and apparently inevitable, revolution being waged – putting greens, tennis courts, welcome mats, front lawns, rooftop parks, surrounding the family swimming pool. Seemingly everywhere you turned there was a grass-like rug lying beneath your feet.

Many baseball teams, some with new stadiums in progress, seriously considered synthetic surfaces in the late 1960s, as was regularly reported in the press. The first outdoor baseball field with artificial grass was Memorial Stadium in York, Pennsylvania, home of Pittsburgh’s Eastern League (Double-A) affiliate. The Pirates were considering the surface for their new facility being constructed in Pittsburgh, while Monsanto was so eager to show off its product that it agreed to install the surface at no cost.

On November 10, 1968, Chicago Bears star Gale Sayers, the best running back in football at the time, suffered a career-altering injury in a game at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. In response, Cubs owner Phil Wrigley told Jerome Holtzman that he would soon be installing artificial turf at Wrigley Field, certainly within a few years. In their conversation there was an overriding understanding that it was better for the players, and that the change was inevitable. This is a man, it should be recalled, who would never install lights at his ballpark.

The Chicago White Sox became the second major-league team to forgo grass, installing a synthetic infield in White Sox Park in 1969, hoping it would lead to higher-scoring games. The first major-league outdoor game on a synthetic surface took place on April 16 when the White Sox beat the expansion Kansas City Royals, 5-2.

Vince Lombardi, coaching the Washington Redskins in 1969, wanted turf installed in RFK Stadium, but Bob Short, who owned the Senators, would not agree. In fact, two years later, when the Senators moved to Texas, Short insisted that turf not be installed at Arlington Stadium, which had been the plan. Short was one of the earliest baseball leaders willing to march against the tide. But the tide kept coming.

The next season brought four new turf fields, beginning with the conversion of the grass surfaces in San Francisco’s Candlestick Park and St. Louis’s Busch Stadium. The first outdoor NL game on turf saw the Astros beat the Giants, 8-5, in San Francisco on April 7. Three days later the Cardinals became the fourth team with Astroturf, and they celebrated with a 7-3 victory over the Mets.

In midsummer, two new ballparks opened with artificial surfaces. Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium debuted on June 30, featuring (for the first time in the major leagues) dirt cutouts around the bases – a characteristic first showcased at Portland, Oregon’s Civic Stadium. The next month the Pirates opened Three Rivers Stadium with Tartan Turf, 3M’s rival product to Monsanto’s AstroTurf. The season also showcased the new surfaces in the postseason for the first time, as Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, in their brand-new parks, met in the NLCS with the Reds advancing to the World Series. It would be 18 years until baseball had another postseason with all-grass fields.

Sometime in the mid-1970s, baseball turned its pivot foot on this issue, though we all had to wait nearly a generation for all of these parks to be replaced. In 1970, not only were all new parks being introduced with artificial surfaces, but existing parks were replacing their natural grass. Within a few years, the new turfs (and the symmetrical concrete stadiums that housed them) were no longer looked upon as progress, but as a sign that the modern world had gone seriously awry. Dick Allen, future horse breeder, remarked, “If horses can’t eat it, I don’t want to play on it.”1 Though his wit was typically unique, his sentiments were carrying the day.

After the two converts in 1970, no baseball park would ever again remove its natural grass in favor of an artificial surface. In fact, the White Sox became the first team to reinstall grass, in 1976, and the Giants followed suit in 1979. The last outdoor baseball facility to debut in the major leagues with an artificial surface was Toronto’s Exhibition Stadium in 1977. There were three new synthetic fields built in the 1980s, but they were all under domes – in Minneapolis, Toronto (retractable), and St. Petersburg. The latter park was built in order to entice baseball to award the city a franchise, but by the time it got its team in 1998, the 10-year-old hardly-used facility was a dinosaur.

The visible effects of the shift away from fake grass had to wait for an entire generation of stadiums to be replaced, a process that began in the 1990s. The nine new stadiums completed between 1970 and 1990 (beginning with Riverfront and Three Rivers and ending with the dome in St. Petersburg, opened in 1990) all had synthetic surfaces. Starting with the new Comiskey Park (later US Cellular) in 1991, major-league baseball has christened 22 new baseball parks, every single one with real grass. There were still 10 artificial surfaces used in 1994, and nine in 1998, but today there are just two, in Toronto and St. Petersburg. Of these, Toronto probably could switch to grass, since its roof retracts and all other retractable roof fields have grass. Tampa Bay is likely stuck, though the team has been trying to get a new park built for many years.

The following chart shows the trend.

Artificial turf still lives on in pro and college football, though in reduced numbers. The surfaces have improved in many ways – many of them look more like grass than they used to, players run and cut better than in days past, and there are fewer funny turf bounces on the newer surfaces. That said, it is unlikely baseball will be returning to those days. The fans, media and players are united on that score.

Artificial turf in baseball is an anachronism today, and the mere mention of the subject is no longer considered appropriate in polite company. But make no mistake: The introduction of Astroturf in 1966 had a huge impact on the way the game was played for two decades, two of the best decades in baseball’s history. Some of the more interesting teams of the era – the Big Red Machine, the “We are Family” Pirates, Herzog’s Cardinals, George Brett’s Royals, the 1980 Phillies – were defined by the fields they played on. In our mind’s eye, when we see Brett and Ozzie Smith and Mike Schmidt, they are running, and diving, and hitting on a lime green carpet.

MARK ARMOUR is the founder and director of SABR’s Baseball Biography Project (BioProject) and is a prolific writer on baseball topics. He lives with Jane, Maya, and Drew in Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

Sources

This is a revised and updated version of an article I wrote for Baseball Analysts website in 2005. In writing the original piece I used the archives of The Sporting News (available through Paper of Record, and free to SABR members) and retrosheet.org.

Notes