The Cold War, a Red Scare, and the New York Giants’ Historic Tour of Japan in 1953

This article was written by Steven Wisensale

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

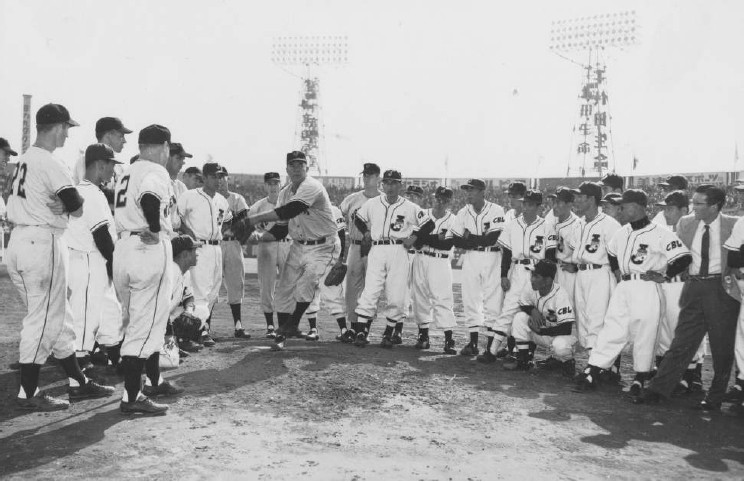

Freddie Fitzsimmons of the New York Giants gives a pitching clinic for the All-Japan team. (Courtesy of the San Francisco Giants)

On the morning of June 29, 1953, readers of the Globe Gazette in Mason City, Iowa, were greeted by a headline on page 13: “New York Giants Invited to Tour Japan This Fall.”1

The Associated Press in Tokyo reported that Shoji Yasuda, president of the Yomiuri Shimbun, had formally invited Horace Stoneham, owner of the New York Giants, to bring his team to Japan for a goodwill tour after the season. The tour was to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Commodore Matthew Perry’s arrival in Japan in 1853, when he forced the isolated nation’s ports to open to the world.2

An excited Stoneham quickly sought and was given approval for the trip from the US State Department, the Defense Department, and the US Embassy in Tokyo. The tour was also endorsed by Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick. However, two hurdles remained for Stoneham: He needed his fellow owners to suspend the rule that prohibited more than three members of a major-league team from playing in postseason exhibition games.3 And at least 15 Giants on the major-league roster had to vote yes for the tour.

With respect to the first hurdle, previous postseason tours had consisted primarily of major-league allstars, not complete teams. The 1953 Giants, however, became trailblazers as the first squad to tour Japan as a complete major-league team.4 The second rule was a requirement set forth by the Japanese sponsors of the tour. They wanted their Japanese players to compete against top-quality major leaguers.

WAIVER IS GRANTED

The waiver Stoneham sought was granted by team owners on July 12 when they gathered in Cincinnati for the All-Star Game “We will now proceed with our plans for the goodwill tour,” said an upbeat Stoneham.5

Another person who was extremely happy with the owners’ decision to support the Giants’ tour of Japan was Tsuneo “Cappy” Harada. Harada was a US Army officer serving with the American occupation force in postwar Japan and an adviser to the Yomiuri Giants. One of his tasks was to restore morale among the Japanese people through sports, particularly baseball. It was Harada who suggested to General Douglas MacArthur that the San Francisco Seals be invited to Japan for a goodwill tour in 1949.6 Working closely with Lefty O’Doul, Harada coordinated the tour, which MacArthur later declared was “the greatest piece of diplomacy ever,” adding, “all the diplomats put together would not have been able to do this.”7 O’Doul would play a central role in 1953 by assisting Harada in coordinating the Giants’ tour.8

After the owners granted approval, Harada flew to Honolulu, where he met with city officials and baseball executives to share the news that Hawaii would host two exhibition games during the team’s layover on their journey to Japan.

At a press conference on July 18 in Honolulu, Harada explained why the Giants were chosen for the tour: They were the oldest team in major-league baseball, and they had Black players. A Honolulu sports- writer observed: “The presence of colored stars on the team will help show the people of Japan democracy at work and point out to them that all the people in the United States are treated equally.”9

Harada’s statement was not exactly accurate. First, while the Giants were one of the oldest professional teams, they were not the oldest. Five other teams preceded them: the Braves, Cubs, Cardinals, Pirates, and Reds. And Harada’s statements regarding racial diversity and “equality for all” were misleading. By the end of the 1953 season only eight of the 16 major-league clubs were integrated. Jim Crow laws were firmly in place in at least 17 states and the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which ended segregated schooling, was a year away. However, Harada was correct in emphasizing the visual impact an integrated baseball team on the field could have on fans, and society as a whole, as Jackie Robinson taught America in 1947.10

The Giants also were selected because of Harada’s close relationship with Lefty O’Doul and O’Doul’s strong connection to Horace Stoneham, which began in 1928 when Lefty played for the Giants. At one point Stoneham even considered hiring O’Doul as his manager.11 Harada, who was bilingual, lived in Santa Maria, California, where, in the spring of 1953, he arranged for the Yomiuri Giants to hold their spring-training camp. Working closely together, Harada and O’Doul (with Stoneham’s approval) scheduled an exhibition game in Santa Maria between the New York Giants and their Tokyo namesake. O’Doul introduced Harada to Stoneham, and the seeds for the Japan tour were planted.12

A CLUBHOUSE VOTE

The one remaining hurdle was a positive vote by at least 15 Giants. Prior to voting, they were told that the tour would take place from mid-October to mid-November. They would play two games in Hawaii on their way to Japan, 14 games in Japan, and a few games in Okinawa, the Philippines, and Guam before returning home. They understood that all expenses would be covered by the Japanese, and they should expect to make about $3,000, depending on paid attendance at the games. On July 25, when the Giants lost, 7-5, to the Cincinnati Reds on a Saturday afternoon before 8,454 fans at the Polo Grounds, the team voted 18 to 7 to go to Japan.

Two players who voted yes were Sal Maglie and Hoyt Wilhelm. Several weeks later Maglie backed out, citing his ailing back, which needed to heal during the offseason. Ronnie Samford, an infielder and the only minor leaguer to make the trip, replaced Maglie. Hoyt Wilhelm faced a dilemma: His wife was pregnant. But his brother was serving in Korea. He chose to make the trip when he learned he could visit his brother during the tour.

Only two players’ wives opted to make the trip and at least one dropped out prior to departure.13 One obvious absentee was the Giants’ sensational center fielder who was the Rookie of the Year in 1951: Willie Mays. Serving in an Army transport unit in Virginia, he would not be discharged until after the tour ended, but in time for Opening Day in 1954.14

Players who voted no provided a variety of reasons for their decisions. Alvin Dark and Whitey Lockman cited business commitments made before the invitation arrived; Rubén Gómez was committed to playing another season of winter ball in his native Puerto Rico; Bobby Thomson’s wife was pregnant; Larry Jansen preferred to stay home with his large family in Oregon; and Dave Koslo wanted to rest his aging arm. Tookie Gilbert also voted no but offered no reason for his decision.15

Nonplayers in the traveling party included owner Stoneham and his son, Peter; manager Leo Durocher and his wife, Hollywood actress Laraine Day; Commissioner Frick and his wife; Mr. and Mrs. Lefty O’Doul; equipment manager Eddie Logan; publicist Billy Goodrich; team secretary Eddie Brannick and his wife; and coach Fred Fitzsimmons and his wife.16 Also making the trip was National League umpire Larry Goetz, who was appointed by National League President Warren Giles and Commissioner Frick.17

The traveling party’s itinerary was straightforward. Most members left New York on October 8 and, after meeting the rest of the group in San Francisco, flew to Hawaii on October 9 and played two exhibition games. They left Honolulu on October 12 and arrived in Tokyo on October 14. After completing their 14-game schedule against Japanese teams, they left Tokyo on November 10 for Okinawa, the Philippines, and Guam before returning to the United States.18

Another team of major leaguers was touring Japan at the same time. Eddie Lopat’s All-Stars, including future Hall of Famers Yogi Berra, Enos Slaughter, Eddie Mathews, Nellie Fox, Robin Roberts, and Bob Lemon, and recent World Series hero Billy Martin, were sponsored by the Mainichi newspaper, one of Yomiuri Shimbun’s major competitors. Lopat’s team won 11 of 12 games and earned more money than the New York Giants.19

THE TOUR IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

When Dwight D. Eisenhower assumed the US presidency on January 20, 1953, he inherited a Cold War abroad that was intertwined with the nation’s second Red Scare at home.20 The Soviet Union engulfed Eastern Europe with what Winston Churchill referred to as an iron curtain; and China, which witnessed a Communist revolution in 1949, became a major threat in Asia. On June 25, 1950, nearly 100,000 North Korean troops invaded US-backed South Korea, commencing the Korean War, which lasted until 1953.

The invasion had a major impact on Japan-US relations. In particular, the United States had to reevaluate how to address the rise of communism in Asia as well as quell the growing opposition to US military bases in Japan. On September 8, 1951, representatives of both countries met in San Francisco to sign the Treaty of Peace that officially ended World War II and the seven-year Allied occupation of Japan, which would take effect in the spring of 1952. Japan would be a sovereign nation again, but the United States would still maintain military bases there for security reasons that would benefit both countries. In short, “it was during the Korean War that US-Japan relations changed dramatically from occupation status to one of a security partnership in Asia,” opined an American journalist.21 And such an arrangement needed to be nurtured by soft-power diplomacy in the form of educational exchanges, visits by entertainers, and tours by major-league baseball clubs. In 1953 the New York Giants served as exemplars of soft power under the new partnership between the United States and Japan.22

A CELEBRATORY ARRIVAL AND A SUCCESSFUL TOUR

The Giants easily won their two games in Hawaii. The first was a 7-2 win against a team of service allstars, and the second was a 10-1 victory over the Rural Red Sox, the Hawaii League champions in 1953. Also present in Honolulu was Cappy Harada, who talked of his dream of seeing a “real World Series” between the US and Japanese champions, while emphasizing that the quality of Japanese baseball was getting closer to the level of play of American teams. He noted that the Yomiuri Giants and the New York Giants had split two games during spring training. “We beat the Americans in California and they beat us in Arizona,” he said. Then, almost in the form of a warning to the traveling party that was about to depart for Japan, Harada reminded reporters that Yomiuri was a powerhouse, having led its league by 16 games.23

When the Pan American Stratocruiser carrying the Giants landed at Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport at 1:00 P.M. on October 14, it was swarmed by Japanese officials, reporters, photographers, and fans. Consequently, the traveling party could not move off the tarmac for more than an hour before boarding cars for a motorcade that wound its way through Tokyo streets lined with thousands of cheering fans waving flags, hoping to get a glimpse of the American ballplayers.24

That evening in the lobby of the Imperial Hotel, Leo Durocher boldly stated that he expected his Giants to win every game on the tour. He also expected a home-run barrage by his club because the Japanese ballparks were so small. “We shouldn’t drop a game to any of these teams while we’re over here,” he boasted. Perhaps realizing that his comment was not the most diplomatic way to open the tour, Durocher quickly put a positive spin on his view of the Yomiuri Giants in particular. “They are the best-looking Japanese ball team I’ve seen,” he said. “They showed a great deal of improvement during their spring workouts in the States.”25 Yomiuri would win their third straight Japanese championship two days later.

Over the next two days, the visiting Giants attended a large welcoming luncheon, participated in a motorcade parade through Tokyo, and held workouts at Korakuen Stadium. “Giants Drill, Leo’s Antics Delight Fans” read a headline in Pacific Stars and Stripes on October 16, the day before the series opened.26 Each day Durocher and several of his players conducted a one-hour clinic on the “fundamentals of American baseball.” A photo captured the Giants demonstrating a rundown play between third base and home.27

Before the Giants’ arrival, the US Armed Forces newspaper Stars and Stripes published a two-page spread profiling the players on both teams.28 For the Japanese people, a Fan’s Guide was distributed widely. Gracing the cover was a color photograph of Leo Durocher with his arm around Yomiuri Giants manager Shigeru Mizuhara, a World War II veteran who had spent five years in a Soviet prison. Inside the guide were ads linked to baseball and numerous photos and profiles of players from both the New York Giants and Eddie Lopat’s All-Stars. Near the back of the guide, however, was an error: a photo of Mickey Mantle. Mantle had backed out of the trip with Eddie Lopat to undergo knee surgery in Missouri.29

THE GAMES

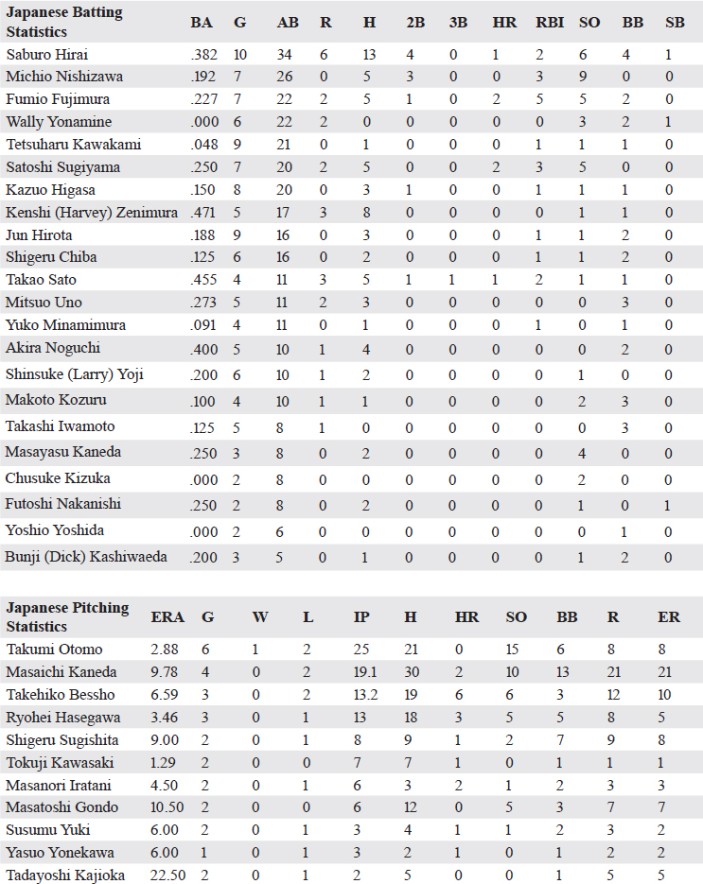

The team’s 14-game schedule was broken down into five games with the Yomiuri Giants, five games against the Central League All-Stars, two games with the All-Japan All-Stars, and single contests with the Chunichi Dragons and the Hanshin Tigers. The first three games were played in Tokyo’s Korakuen Stadium, which held 45,000 fans.

The ceremonies before the first game were lavish. There were speeches and an exchange of gifts. The mayor of Tokyo gave Durocher a key to the city and a gift for his wife. Durocher returned the favor by giving a New York Giants banner to the mayor. At one point Ford Frick stepped before the microphone to share a letter from President Eisenhower: “Dear Mr. Frick: I was delighted to hear that through your good offices the plan for the Japanese tour of the New York Giants has been successfully completed. For myself, I enthusiastically support this kind of sporting and human relationship between the people of Japan and the U.S. The United States of America seeks the friendship of all, the enmity of none—for in real friendship there is strength and only through strength can come the peace and freedom which mean happiness and well-being for the world.” Japanese Premier Shigeru Yoshida welcomed the New York Giants to Japan and said of the visit: “I hope it will be significant not only for the Japanese baseball world but for goodwill and a better understanding between both peoples.” Shortly after the exchange of gifts and greetings, a helicopter hovered above the ballpark and dropped the game ball by a small parachute onto the infield.30

Whatever dreams Cappy Harada harbored about a “real World Series” were certainly smashed temporarily as he watched Durocher’s Giants crush his Yomiuri Giants, 11-1, before a capacity crowd. The Giants hammered out 12 hits, including home runs by outfielders Dusty Rhodes and Monte Irvin. Starting pitcher Al Worthington, who went five scoreless innings, and reliever Hoyt Wilhelm, who pitched the final four innings, held Yomiuri to one run on seven hits. In a losing cause, 36-year-old third baseman Mitsuo Uno collected a pair of hits against New York’s pitchers.31

Games two and three of the tour were also played in Korakuen Stadium, again before capacity crowds. In game two against the Central League All-Stars, the Giants won, but not as convincingly as the day before. The Japanese squad led 3-0 after the first two innings, but the New Yorkers scored two runs in the third before Hank Thompson tripled in the fifth to tie the game. Don Mueller’s home run in the ninth inning finished off the All-Stars, 5-3. After the game, Durocher praised Japan’s pitching and particularly the performance of 20-year-old Masaichi Kaneda of the Kokutetsu Swallows. “I wish we had that guy,” said Durocher. “As a matter of fact, I think he could make any Class A club in the States.”32 The reference to A-level baseball and on rare occasions to Double-A baseball was as high as assessments went by Americans on the tour. Neither Durocher nor Frick ever labeled Japanese baseball in general, or any one player in particular, above the US Double-A level.

Game three was another low-scoring contest against the Japanese All-Stars. Solo home runs by center fielder Dusty Rhodes and shortstop Daryl Spencer led the offense. Seven solid innings of pitching by Jim Hearn and effective relief by Hoyt Wilhelm in the final two innings gave the Giants their third win in a row, a 4-1 victory.33 In their first three games in Tokyo, the Giants drew 128,000 fans, more than 42,000 pergame.

As the Giants moved into more rural regions of the country, attendance declined and so did news coverage. Games four and five were played before smaller crowds in Sapporo and Sendai, both in northern Japan. In game four, the New York Giants once again demolished the Yomiuri Giants, 8-1, thanks to A1 Worthington’s one-hit pitching for seven innings. Durocher’s offense was highlighted by a triple from Monte Irvin.34 In game five in Sendai, the Giants broke open a 4-4 tie in the seventh inning to defeat a combined Yomiuri-Kokutetsu squad, 10-4. Don Mueller had four hits and Monte Irvin had three to lead the assault. Masaichi Kaneda, the young pitcher Durocher wished he had, gave up 15 hits.

The Giants continued their winning ways in games six through nine. In game six they defeated Yomiuri, 4-1, in Shizuoka for the third time in as many games, this time beating their ace pitcher Takehiko Bessho.35 Traveling on to Nagoya on October 24, the Giants defeated the Chunichi Dragons, 9-6, but had to overcome an early 6-0 deficit.36 On October 26 the pitching performance of the tour was turned in by Marv Grissom in Okayama against the Pacific League AllStars. Pitching a complete game, he surrendered only three hits in the 4-0 shutout, while striking out 15. At one point he struck out six in a row.37 Two days later in Hiroshima, the Giants got another outstanding pitching performance, this time from Jim Hearn, as they squeaked by with a 3-2 win over the Central League All-Stars.38

The highlight of the tour for Japanese fans came on October 31 when a crowd of 30,000 at Tokyo’s Korakuen Stadium saw their Giants finally defeat the Americans, 2-1. The stars of the game were Takumi Otomo, who gave up one run on seven hits, and shortstop Saburo Hirai, who hit a go-ahead home run off Hoyt Wilhelm in the eighth inning. The victory was only the fourth by a Japanese team against an American major-league team since 1920. This game was also unique in another respect. Lefty O’Doul sat in the Tokyo dugout advising manager Mizuhara on how to pitch to New York’s hitters. In short, O’Doul may have been Japan’s first bench coach, as he constantly reminded Otomo to pitch the Americans high in the zone rather than low, where they preferred their pitches.39

Perhaps embarrassed by their first defeat, Durocher’s team unleashed a 23-hit attack that produced a 16-5 win over the Central League All-Stars in Tokyo in the 11th game of the tour. Leading the assault was Dusty Rhodes, who drilled three home runs into the right-field seats. Hank Thompson, A1 Corwin, Sam Calderone, and Monte Irvin also hit homers in the rout.40 After traveling to Hamamatsu for game 12, where they played the Central League All-Stars to a 4-4 tie in a game called because of darkness after nine innings, the tour paused for a side trip to Korea between November 3 and 5.41 Leo Durocher, coach Fred Fitzsimmons, umpire Larry Goetz, and seven players visited American troops on several military bases. The players were Dusty Rhodes, Sam Calderone, Bill Rigney, Monte Irvin, Bobby Holman, Don Mueller, and Hoyt Wilhelm, who had a chance to visit his brother on the front lines.42

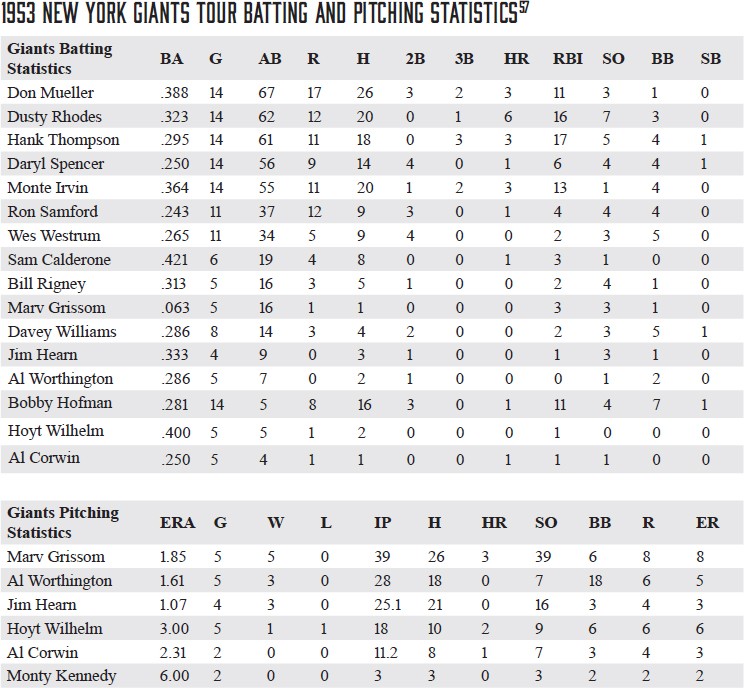

If the New Yorkers wanted to make a definitive statement about the superiority of American baseball over Japanese ball, they did so in the last two games of the tour, outscoring their opponents 19-0. In game 13 in Osaka on November 6, the Giants scored 12 runs on 14 hits to support another brilliant pitching job by Marv Grissom, who shut out Osaka on six hits. Ronnie Samford, Hank Thompson, and Monte Irvin hit home runs to lead the attack.43 And in the final game of the tour, a similar picture was painted. In a convincing 7-0 win over the Japanese All-Stars, A1 Worthington tossed a three-hitter, and was backed by a 15-hit attack led by Monte Irvin, Dusty Rhodes, and Bobby Hofman, who all produced extra-base hits. In an award ceremony after the game, Marv Grissom and Don Mueller were each given 30,000 yen (about $84 in 1953 dollars) for the best pitcher and hitter on the tour. Mueller hit .388 followed by Monte Irvin at .364. Dusty Rhodes led the team in home runs with six, less than half of Babe Ruth’s output of 13 homers in during the 1934 tour.44

A TRANSACTION LOST IN TRANSLATION?

The second game in Osaka was almost forfeited and the diplomatic mission tarnished when six of the Giants players, claiming they had heard their final pay for the tour would be $331 and not $3,000, threatened to boycott the game. Still in street clothes, the six Giants—Jim Hearn, A1 Worthington, Hoyt Wilhelm, A1 Corwin, Sam Calderone, and Daryl Spencer—played cards in the clubhouse while their teammates were in uniform. According to the original agreement, the players were to get a 60 percent cut of the ticket sales for the last two games of the tour. However, when they learned that only 5,000 of the 24,000 fans in the stands in game one in Osaka actually paid for a ticket, and that only 12,800 fans of 35,000 fans in the stands for the second game bought tickets, the six players revolted.

Only after Durocher huddled with officials from Yomiuri Shimbun and the players were assured they would be paid $1,000, did they suit up and go on the field. Some players had passed up lucrative offseason job opportunities to make the trip. Monte Irvin, for example, earned $7,000 every winter as a luncheon and dinner speaker for a beer distributor.45 To make matters worse, perhaps, the Giants learned later that each of Eddie Lopat’s All-Stars earned $4,000 for their trip—and did so without any “lost in translation” type of episodes.46 It was as late as November 25 that confusion over the final payout continued when an anonymous Giants player disclosed that in the end each player got only about $660, not the $1,000 that was reported.47

With the Osaka incident behind them, the team left Japan with a record of 12 wins, one loss, and a tie. They continued on to Okinawa, the Philippines, and Guam where they played exhibition games against US service teams, winning two of three, before returning home. Little did they realize during their return flight that the team that finished 35 games out of first place in 1953 would be World Series champions a year later. Whether or not the tour was a team bonding experience for Durocher and his players is open to question, but the thought deserves some consideration.

A DREAM DEFERRED FDR CAPPY HARADA

In news coverage throughout the tour, Durocher, Stoneham, and Frick occasionally flirted with Cappy Harada’s concept of a “real World Series” between American and Japanese winners, but quickly directed their attention toward the play of individual Japanese players, rather than discuss a complete Nippon team being on par with US major-league teams. The Americans’ view that the quality of Nippon baseball in 1953 fell somewhere between A and Double-A level was probably accurate. After all, the Americans dominated the Japanese throughout the tour. They defeated the league champion Yomiuri Giants four out of five times and also beat two sets of all-star teams as well as the Chunichi Dragons and the Hanshin Tigers rather handily in most cases. They outscored their Japanese opponents 102-45 and outhit them 173-94, while holding the Japanese hitters to a .195 batting average.48 Even more sobering for Harada and Nippon baseball was that seven of New York’s top stars did not even make the trip. Whatever parity existed between the Americans and the Japanese, it was in their defensive play: The New York Giants committed 18 errors, while the Japanese teams had 11 errors combined. On several occasions Frick praised the sound fundamentals exhibited by the Japanese during the tour.49

Opening ceremonies for the New York Giants in Osaka. (Courtesy of the San Francisco Giants)

However, despite the disappointing outcome for Japan, at least three Japanese players captured the attention of the New York club during the tour. One was Masaichi Kaneda of the Kokutetsu Swallows, who pitched effectively against the New Yorkers in game two, earning praise from Durocher.50 Also of interest was Saburo Hirai, the Yomiuri shortstop, who hit .382 in 34 at-bats with four doubles and a home run. Pacific Stars and Stripes described him as “a player whose glove work was almost unbelievable. He is a solid right-handed hitter, a long-ball man, a terror on the bases and one of the top figures in Japanese baseball.”51

But most impressive perhaps was Takumi Otomo of the Yomiuri Giants, winner of the 1953 Sawamura Award as the best pitcher in Japanese baseball. Otomo had a 27-6 won-lost record, 173 strikeouts, and a 1.86 ERA in 281⅓ innings in 1953.52 It was Otomo who held the New York club to one run in the only win recorded by a Japanese team during the tour. In 25 innings he struck out 15 hitters and produced an impressive 2.88 ERA, which was about 3.5 runs below the composite ERA of Japanese pitchers who faced Durocher’s club. An attempt by Stoneham to sign him to a contract failed as Yomiuri’s asking price of $10,000 plus three American ballplayers was much too high for Stoneham. Little did the Giants owner realize that he would have to wait 11 years before having another opportunity to sign a Japanese player.53

A fourth player who was clearly on the Giants’ radar screen during the tour was Yomiuri’s Wally Yonamine. The Hawaii native, who is referred to as “the man who changed Japanese baseball,” was the first American to play professional ball in Japan after the war, arriving in 1951. He had a stellar career, collecting three batting titles and an MVP award. He was honored by the emperor and inducted into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame. However, whatever interest the Giants may have had in Yonamine in 1953 probably vanished quickly, as they watched the Yomiuri center fielder go 0-for-22 at the plate in five games.54

Clearly, Cappy Harada’s dream of a “real World Series” was not realistic in 1953, nor is it much more feasible today. Other than the flirtation with such a fantasy every four years in the form of the World Baseball Classic that Japan has captured twice (as of 2022) since its inception in 2006, a “real World Series” is not yet visible on the horizon. At least for now, the Japanese baseball hierarchy will have to be satisfied with the individual performances of players like Masanori Murakami, Hideo Nomo, Hideki Matsui, Ichiro Suzuki, and Shohei Ohtani in the United States as a proxy for some measure of baseball equivalency between the two nations. More importantly, however, the 1953 tour served as a good example of “soft power diplomacy” at a crucial point in the diplomatic history of Japan-US relations. It was the early years of the Cold War and at the height of the Red Scare when the Giants journeyed to Japan. It was less than a year after America’s role as an occupying force ended and a new partnership of cooperation between the two countries began. What the New York Giants did in Japan in 1953 mattered.

EPILOGUE

The day after the Giants departed Haneda International Airport, Vice President Richard Nixon arrived in Tokyo to deliver a speech before the American-Japan Society. He emphasized the importance of US-Japan relations in the postwar period, especially after the Communist takeover of China. He reminded his audience that if Japan fell under Communist domination, so would all of Asia. Therefore, he argued, although disarmament was an important goal, Japan needed to increase its forces and forge closer ties with South Korea in order to defend Southeast Asia. The domino theory that would dominate American foreign policy for decades was operative, and major US involvement in Vietnam was only a decade away.55

On February 7, 1954, less than three months after Nixon’s speech in Tokyo, there appeared on the front page of the Sunday New York Times sports section a photograph of Commissioner Frick and Giants owner Stoneham presenting President Dwight D. Eisenhower a gift from the Japanese people in appreciation of the Giants’ goodwill tour. Accompanying the photo was a story that described the gift as a 110-pound [sic] Samurai battle protector in the form of “a suit of metal and cloth armor worn in Japan during the Shogun dynasty more than 700 years ago [that] was given to President Eisenhower today on behalf of the baseball fans of Japan.” The photo caption explained that the presentation was made on behalf of Matsutaro Shoriki, owner of the Yomiuri Shimbun and regarded as the “father” of professional baseball in Japan.56

The bases had been circled, and at least one of many diplomatic missions had been completed, but many more tours would follow, as two nations, once at war, grew closer together. What appeared as a small, obscure story on page 13 of the Globe Democrat in Mason City, Iowa, on June 29, 1953, grew into a story of much more significance, earning a place on the front page of the New York Times sports section seven months later. Perhaps Yogi Berra could best summarize the importance of the Giants tour in 1953 with his own concise words of wisdom: “Little things are big,” said Yogi.

STEVEN K. WISENSALE, PhD., is professor emeritus of public policy at the University of Connecticut, where he taught a very popular course for many years: “Baseball and Society: Politics, Economics, Race and Gender.” In 2017 he traveled to Japan as a Fulbright Scholar where he designed and taught another course, “Baseball Diplomacy in Japan-US Relations,” at two universities. His most recent SABR publications include “The Black Knight: A Political Portrait of Jackie Robinson” (a chapter in Jackie: Perspectives on 42) and “In Search of Babe Ruth’s Statue in a Japanese Zoo” (Baseball Research Journal, spring 2021). He is also a regular attendee and an occasional presenter at the Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture. An avid Orioles fan, Steve resides in Essex, Connecticut, with his wife Nan and their two dogs, Song and Blue Moon, who can run down deep fly balls consistently for very low wages and without pulling a hamstring.

NOTES

1 “New York Giants Invited to Tour Japan This Fall,” Mason City (Iowa) Globe Gazette, June 29, 1953: 13.

2 For more information on this topic refer to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators website at Commodore Perry and Japan (1853-1854), http://afe.easia.columbia.edU/tps/1750_jp.htm#perry.

3 Restrictions on barnstorming tours can be traced back to 1921-1922 under Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

4 The New York Giants under John McGraw and the Chicago White Sox under Charles Comiskey toured Japan together in 1913 but the rosters were heavily supplemented with players from other teams.

5 “Cleveland Awarded 1954 All-Star Game; N.Y. Giants’ Tour of Japan Okayed,” Allentown(Pennsylvania) Morning Call, July 13, 1953: 12.

6 Robert K. Fitts, Remembering Japanese Baseball: An Oral History of the Game (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), 3.

7 Dennis Snelling, Lefty O’Doul: Baseball’s Forgotten Ambassador (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 243.

8 Snelling, 236.

9 Andrew Mitsukado, “Giants Receive Japan Bid to Play 12-Game Series f Honolulu Advertiser, July 19, 1953: 20.

10 In the fall of 1953 Jackie Robinson’s integrated barnstorming team was banned from taking the field in Birmingham, Alabama, by Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene “Bull” Connor, who was notorious for using police dogs and firehoses against civil-rights demonstrators.

11 Snelling,39;Fitts, Remembering Japanese Baseball, 1-10.

12 Steven Treder, Forty Years a Giant: The Life of Horace Stoneham (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2021), 167.

13 “18 Giants to Make Trip to Japan, Philippines,” New York Herald Tribune, July 26, 1953: B 2.

14 The Giants repeatedly sought an early discharge for Mays but failed, even after his mother died giving birth to her nth child. See Treder, 170.

15 Arch Murray, “Giants in Japan, Trip Hailed as Aid in International Affairs,” The Sporting News, October 14, 1953: 19.

16 New York Herald Tribune, July 26, 1953: B 2.

17 “Giles Picks Goetz for Japan Tour,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 3, 1953: 18. Goetz got upset early on when he heard fans shouting “goetsu, goetsu,” thinking they were saying something derogatory about him. He relaxed when he learned the fans were simply saying “get two, get two” as in a double play.

18 “Giants’ Itinerary,” The Sporting News, October 14, 1953: 19.

19 “Martin Arrives Home, Praises Japan Junket,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 13, 1953: 21. During a post-tour interview in Oakland, Martin stated that each of the Eddie Lopat All-Stars made about $4,000.

20 In 1953 Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisconsin) in 143 days of hearings questioned more than 600 witnesses in an effort to identify and expel communists in government and other institutions. The Cincinnati Reds became the Redlegs for six years to avoid being confused with the “Russian Reds.”

21 Olivia B. Waxman, “How the US and Japan Became Allies Even After Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” Time, August 6, 2018: 23.

22 Harvard professor Joseph Nye coined the term “soft power” in 1990. Soft power is defined as a collaborative act that lies in the ability to attract and persuade another person or country to do something that benefits both. Hard power is the use of military or economic might to coerce person or country to do something.

23 >Carl Machado, “Lefty O’Doul Says PCL in Best Shape in History,” Honolulu Star Bulletin, October 10, 1953: 6.

24 “New York Club Arrives in Japan,” Tampa Tribune, October 15, 1953: 2-B.

25 Sgt. Mike Hickey, “Durocher Sees Clean Sweep in Games with Tokyo Giants,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 15, 1953: 14.

26 Sgt. Mike Hickey, “Giants Drill, Leo’s Antics Delight Fans,” Facific Stars and Stripes, October 16, 1953: 14.

27 Cpl. Pete Johnstone (photographer), “Clinical Diagnosis,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 19, 1953: 14.

28 Sgt. Mike Hickey, “Giants vs. Giants,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 3, 1953: 6-7.

29 “Mantle’s Bad Knee Ready for Surgery,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 3, 1953: 18.

30 Associated Press, Tokyo, Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 18, 1953: 13; N. Sakata, “Capacity Crowds Watch Giants in First Four Japanese Games,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1953: 17.

31 “New York Overpowers Tokyo Giants 11-1,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 18, 1953: 13.

32 Sgt. Mike Hickey, “New York Edges All-Stars 5-3,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 19, 1953: 13.

33 Associated Press, “41,000 See Giants Take Third in a Row on Japanese Tour,” St. Louis Globe Democrat, October 20, 1953: 16.

34 Associated Press, “More Than 25,000 See Giants Win Fourth in a Row,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 22, 1953: 11.

35 Associated Press, “Giants Top Tokyo for Sixth Straight,” Scrantonian Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania), October 25, 1953: 44.

36 Associated Press, “Giants Win,” Arizona Daily Star (Tucson), October 26, 1953: 10.

37 “Marv Grissom Fans 15 as New York Giants Win to Maintain Clean Slate,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 28, 1953: 13.

38 Associated Press, “Giants, Lopat’s Stars Win Again,” Nashville Banner, October 29, 1953: 41.

39 Associated Press, “O’Doul Helps Beat Giants,” San Francisco Examiner, November 1, 1953: 47.

40 United Press, “Giants Shellac Japanese,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 1, 1953: 14.

41 Cpl. Perry Smith, “Darkness Stops NY,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November, 1953: 14.

42 “New York Giants Group to Make Korean Junket,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 31, 1953: 18.

43 Cpl. Perry Smith, “Grissom Blanks Osaka as Giants Rap 3 Homers,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 8, 1953: 13.

44 “Durochermen Draw Well During Baseball Junket,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 3, 1953: 15.

45 Cpl. Perry Smith, “Giants Net $331 Each, Expected $3,000.” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 10, 1953: 13. The $331 amount was merely a rumor that was later disproved.

46 “Martin Arrives Home, Praises Japan Junket,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 13, 1953: 21.

47 Larry Jackson, “Giants Earned Only $660 Each on Tour,” The Sporting News, November 25, 1953: 18.

48 Robert K. Fitts, Wally Yonamine: The Man Who Changed Japanese Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 159.

49 Asahi Shimbun, October 18—November 19, 1953. Thank you to Michael Westbay of Japan Ball.com for translating and compiling the box scores.

50 Sgt. Mike Hickey, “New York Edges All-Stars, 5-3,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 19, 1953: 13.

51 Harry Grayson, “Maybe Durocher Can Find His Kind of Giants on One of the Hustling Japanese Clubs,” Elmira (New York) Advertiser,October 28, 1953: 13.

52 Daniel E. Johnson, Japanese Baseball: A Statistical Handbook (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1999).

53 Fitts, Wally Yonamine, 159.

54 Fitts, Wally Yonamine, 159. Also see Robert K. Fitts, Mashi: The Unfilled Dreams of Masanori Murakami, The First Japanese Major Leaguer (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 39.

55 Jonathan Movroydis, “Vice-President Nixon on the Future of US-Japan Relations,” Richard M. Nixon Presidential Library, October 1, 2018. Nixon’s entire speech can be accessed at Vice President Nixon on the Future of U.S.-Japan Relations, nixonfoundation.org. https://www.mxon-foundation.org/2018/10/vice-president-nixon-future-u-s-japan-relations/.

56 Associated Press, “Japan’s Fans Send Gift to Eisenhower,” New York Times, February 7, 1954: Cl.

57 Listed Japanese players have a minimum of 5 at-bats, 5 innings pitched, or a decision. Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs, U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 90; Nippon Professional Baseball Records, https://www.2689web.com/nb.html.