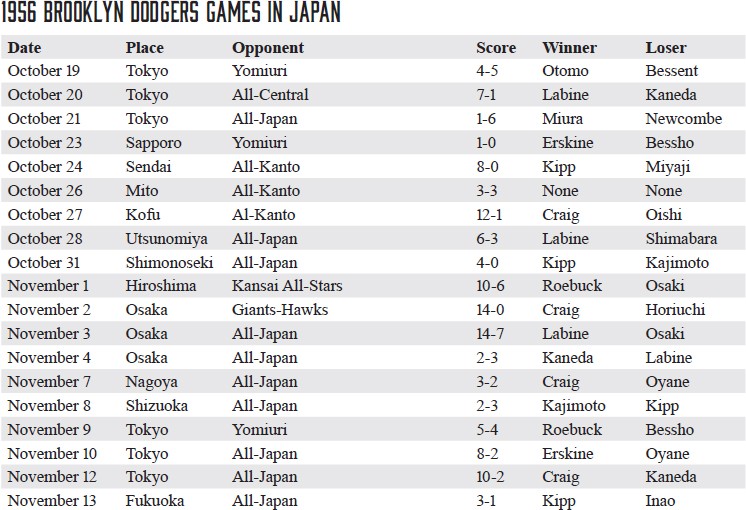

The Bums in the Land of the Rising Sun: How the 1956 Dodgers’ Tour of Japan Marked the End of a Dynasty

This article was written by Rob Fitts

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

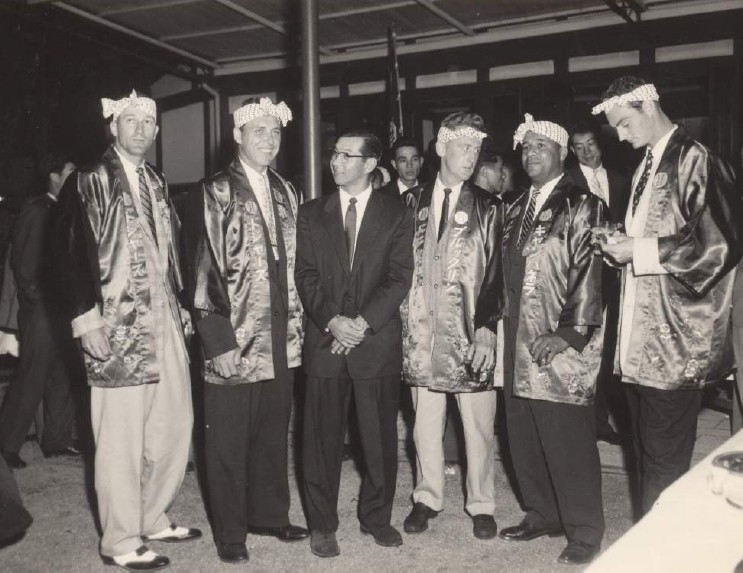

Fred Kipp, Gil Hodges, Wally Yonamine, Vin Scully, Roy Campanella and Don Demeter at the October 18 reception at Chinzanso, Tokyo. (Rob Fitts Collection)

The Brooklyn Dodgers straggled into Idlewild Airport in Jamaica, Queens, on the morning of October 11, 1956. It had been a long, grueling season, ending the day before with a 9-0 shellacking by the Yankees in the seventh game of the World Series. Now, less than 18 hours later, the Dodgers were leaving for a four- week goodwill tour of Japan.

The subdued party of 60 consisted of club officials, players, family members, and an umpire. Although participation was voluntary, most of the team’s top players had decided to take advantage of the $3,000 bonus that came with the all-expenses-paid trip.1 Noticeably absent were Sandy Koufax, who was sharpening his game in Puerto Rico; Sandy Amoros, who was playing in Cuba; and World War II vet Carl Furillo who proclaimed, “I want no part of it. I’ve seen Japan once and there’s nothing there I want to see again.”2

As they readied to board the private flight to Los Angeles, Don Newcombe and his wife were missing. The Dodgers ace had won 27 games during the season and would win both the National League Most Valuable Player and Cy Young Awards. But he had failed spectacularly in the World Series, getting knocked out in the second inning of Game Two, and in the fourth inning of Game Seven. When asked about the up-coming trip after the Game Seven loss, Newcombe snapped, “Nuts to the trip to Japan!” “There’ll be trouble if he’s not on that plane!” countered Dodgers General Manager Buzzie Bavasi.3

Just after 11 A.M. the big pitcher arrived at the airport without wife or luggage. “The Tiger is here!” he announced as he boarded. He had spent the morning at the Brooklyn Courthouse to answer a summons on an assault charge for punching a parking attendant who had made a wisecrack about his Game Two performance. The plane left on time and after a stop in Los Angeles arrived in Honolulu at 5:30 P.M. on October 12.4

The Dodgers spent five days in Hawaii, attending banquets, sightseeing, sunbathing on Waikiki Beach, and playing three games against local semipro teams. As expected, Brooklyn won the first two contests comfortably, beating the Maui All-Stars, 6-0, behind 20-year-old Don Drysdale’s seven perfect innings on October 13 and the Hawaii Milwaukee All-Stars, 19-0, the next day. On the 15th, Don Newcombe took the mound against the Hawaii Red Sox. Spectators serenaded him with boos and jeers as the Red Sox scored three times in the second inning and chased him from the game in the fourth. “I can’t believe that I am still the target for abuse after getting 5,000 miles away from Brooklyn. I never want to come back here again! I didn’t want to make this trip in the first place,” he complained after Brooklyn pulled out a 7-3 win in the 10th inning. “This abuse thing has me worried,” he added. “I am afraid the emotional effect might continue to grow and become a detriment to my future career.”5 After a day of sightseeing, the Dodgers left for Japan on a 10 P.M. overnight flight.

The plane touched down at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport at 3:25 P.M. the following day, five hours behind schedule after mechanical trouble forced a seemingly endless stopover on Wake Island. A light rain fell from the gray sky. The weary players trudged off the plane and down the metal stairs to the tarmac where they were greeted by the first group of dignitaries and reporters. “Man, we’re beat,” Jackie Robinson complained as he left the plane. “We are all very tired,” Duke Snider added, “but we’re glad to be here. If we have a chance to shower and clean up, we’ll feel much better.”6

Japanese dignitaries and 40 kimono-clad actresses, bearing bouquets of flowers, welcomed the Dodgers as a crowd of fans waved from the airport’s spectator ramp. During a brief press conference, team owner Walter O’Malley proclaimed that “his players would play their best … and hoped that the visit would contribute to Japanese-American friendship.” “We hope to give the Japanese fans some thrills,” said Robinson.7

Despite the delay and relentless drizzle, thousands of flag-waving fans lined the 12-mile route from Haneda Airport to downtown Tokyo. Although many of the players longed for a shower, a warm meal, and a soft bed, they would not see their hotel for hours. After a brief stop at the Yomiuri newspaper’s headquarters, the team went straight to a reception at the famous Chinzanso restaurant. As they arrived, the hosts presented each visitor with a happi coat made to resemble a Dodgers warmup jacket and a hachimaki (traditional headband). Dressed in their new garb, the Dodgers mingled with baseball officials, diplomats, and Japanese ballplayers for several hours. Exhausted, the Dodgers finally checked into the Imperial Hotel around 9 P.M. Some of the younger players, however, went back out, attending “a giddy round of parties” before staggering back to the hotel in the wee hours of the morning.8

Weary from the trip and the late night, the players struggled to get out of bed the next morning for the opening game against the Yomiuri Giants at Korakuen Stadium. Ceremonies began at 1 P.M. with the two teams parading onto the field in parallel lines behind a pair of young women clad in fashionable business suits. Each woman held a large sign topped with balloons, bearing the team’s name in Japanese. As the Giants marched on the field, some of the Dodgers gaped in surprise. “We went over there with typical American misconceptions,” Vin Scully later wrote. “We expected the local teams to be stocked with little yellow, bucktooth men wearing thick eyeglasses. When they first walked onto the field in Tokyo, I heard one of our players yell, ‘Hey fellas, we’ve been mousetrapped!’ One of the first ballplayers out of the dugout was a pitcher who was six feet four. … They averaged five feet ten or so, and they were all built like athletes.”9

Like the Dodgers, the Yomiuri Giants had just finished an exhausting season topped with a defeat in the Japan Series two days earlier. The Japan Times noted, “The Giants, battered and worn in their losing bid for the Japan championship …, are regarded as a pushover for the Bums. The Brooklyn club is expected to win their opener by a margin of over ten runs.”10 But that is not what happened.

The Giants jumped out to a quick 3-0 lead off Don Drysdale. At 6-feet-5 he towered over most of his Japanese opponents and expected to dominate them with his overpowering side-arm fastball. But as Scully noted, “Another misconception we had was that our big pitchers would be able to blow them down with fastballs. We were dead wrong. They murdered fastball pitching. Our guys would rear back and fire one through here and invariably the ball would come back even harder than it was thrown. They hit bullets.”11

Brooklyn battled back to take a 4-3 lead in the fourth on five hits, including homers by Robinson and Gil Hodges. But that would be all for Brooklyn as relief pitcher Takumi Otomo, who had beaten the New York Giants in 1953, stifled the Dodgers for 5 2/3 innings. Homers by Kazuhiko Sakazaki and Tetsuharu Kawakami in the eighth gave Yomiuri a 5-4 upset victory. “The fans,” wrote Leslie Nakashima of the Honolulu Advertiser, “could hardly believe the Dodgers had been beaten.”12 Otomo had struck out 10 in his second win over a major-league team.

Since the major-league tours began in 1908, the game was just the fifth victory by a Japanese team against 124 loses.13 After the loss, manager Walt Alston made no excuses, “They just beat us. They hit and we didn’t.” Duke Snider had a particularly bad day, striking out three times and being caught off base for an out. “We’re pretty tired,” he explained. “But that’s no excuse. We’re all in good physical shape and should have won. A good night’s sleep tonight and we’ll roll.” “We’ll snap out of it,” predicted Robinson. Pee Wee Reese agreed: “We don’t expect to lose any more. But,” he added, “we didn’t expect to lose this one either.”14

As predicted, the Dodgers bounced back the next day. Masaichi Kaneda, recognized by most experts as Japan’s all-time greatest pitcher, began the game for the Central League All-Stars by loading the bases on two walks and a single before being removed from the game with a sore elbow. Roy Campanella greeted relief pitcher Noboru Akiyama with a towering drive into the last row of the left-field bleachers to put the Dodgers up, 4-0. Campy added another home run in the third inning to pace Brooklyn to an easy 7-1 victory as Clem Labine pitched a four-hit complete game.15

On Sunday, October 21, approximately 45,000 fans packed Korakuen Stadium to watch Don Newcombe face the All-Japan team—a conglomeration of the top Japanese professionals. Newcombe’s outing lasted just 17 pitches. He began by walking Hawaiian Wally Yonamine, then surrendered a home run and three consecutive singles before Alston took the ball.16 The former ace “stormed from the hill” and stumbled into the clubhouse “like a sleepwalker … jerkily, almost aimlessly. He wore the frozen expression of a kid who’s just seen his puppy run over. Wonder, shock, disbelief, hurt. Pinch me, I’m dreaming. … Slowly he picked up his shower shoes, detoured a sportswriter to get to his jacket. Then out the back door, back to the hotel.”17

After the eventual 6-1 loss, manager Walter Alston noted, “Newk wasn’t right again today. … He’s not throwing natural.”18 Reese explained, “He’s still got it (the World Series) on his mind. It’s getting to be a terrible thing. Not only does he feel he’s letting himself down, he feels he’s letting the club down. … Don doesn’t say much, but it’s building up and building up inside him. It could run him out of baseball.”19

Unfortunately, Reese’s assessment was prophetic. The next day, Newcombe announced that he had injured his elbow in the final game of the regular season. It hurt to throw curveballs. He had kept the injury to himself, hoping that rest would cure the ailment. Although his arm may have healed, Newcombe never fully recovered from the psychological injury of the blown 1956 World Series. He had begun drinking heavily in the early 1950s and his alcohol abuse intensified after the loss. After a mediocre 1957 season, he was traded to Cincinnati in 1958 and would be out of the major leagues after the 1960 season. He played his final season with the Chunichi Dragons of Japan in 1962—coached by Wally Yonamine, who had begun the onslaught on that fateful day in Tokyo.

With the loss, the Dodgers became the first professional American club to lose two games on a Japanese tour. Criticism came from both sides of Pacific. “The touring Flatbushers once again were disemboweled by a band of local samurai,” wrote Bob Bowie of the Japan Times.20 “The Dodgers are known for their fighting spirit,” noted radio quiz-show host Ko Fujiwara, “but they have shown little spirit in the games here thus far.”21 The Associated Press reported that “most Japanese fans have been disappointed in the caliber of ball played so far by the Brooklyns,” but Yoshio Yuasa, the former manager of the Mainichi Orions, offered the harshest criticisms.22 “I can sympathize that the Dodgers are in bad condition from fatigue after a hectic pennant race, the World Series and travel to Japan and that they are in a terrific slump, but they are even weaker than was rumored at bat against low, outside pitches and we are very disappointed to say the least. … It would not be an overstatement to say that we no longer have anything to learn from the Dodgers.”23

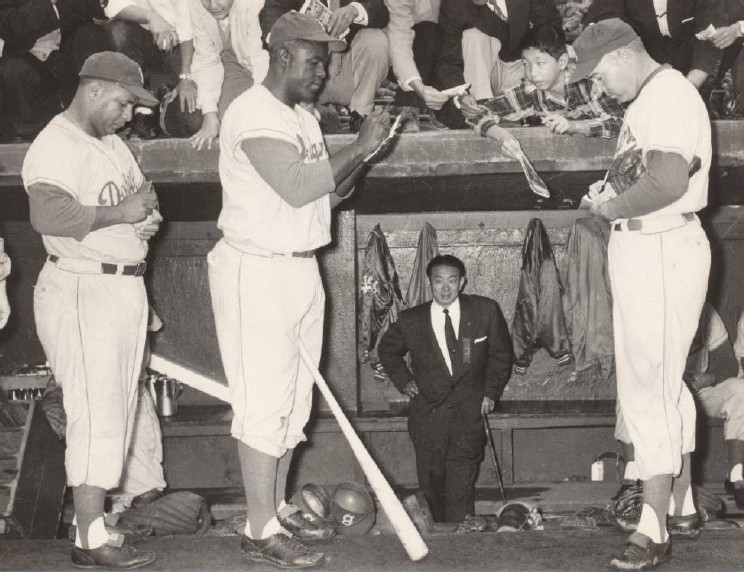

Roy Campanella, Jakie Robinson, and Duke Snider signing autographs for Japanese fans. Cappy Harada is in the dugout. (Rob Fitts Collection)

The US media picked up these criticisms, reprinting the stories in large and small newspapers across the country. “Japanese Baseball Expert Hints Brooks Are Bums,” screamed a headline in the New York Daily News on October 23.24 Three days later, a Daily News headline noted, “Bums ‘Too Dignified,’ Say Japanese Hosts.” The accompanying article explained that some Japanese experts believed that the Dodgers were “too quiet and dignified on the playing field … and … were acting like they were all trying to win good conduct medals” rather than playing hard-nosed baseball.25

After a day of rest, the Dodgers flew to Sapporo in northern Japan for a rematch against the Yomiuri Giants. Before the game, Walter O’Malley addressed the team. Starting pitcher Carl Erskine recalled, “Mr. O’Malley was very upset. He thought it was a scar on the name of the Dodgers to have gone to Japan and lost two games.”26 “He was embarrassed. He held a team meeting and read the riot act. He said, ‘I know this is a goodwill tour and I want you to be gentlemen. Sign autographs and be cordial. However, when you put on that Dodger uniform, I want you to remember Pearl Harbor!’”27

Erskine was near perfect, giving up three hits and a walk but never allowing a runner to reach second base as he faced just 27 batters. But the Dodgers continued to struggle at the plate, failing to score until Duke Snider led off the ninth inning with a 380-foot homer over the right-center-field wall to give Brooklyn a 1-0 victory.28

Despite the win, many Japanese were not pleased with the Dodgers’ performance. An Associated Press article noted that Tokuro Konishi, a broadcaster and former manager, “and other experts agreed that most Japanese fans have been disappointed in the caliber of ball played so far by the Brooklyns. … Konishi said he believed the two losses could be chalked up to the fatigue from the grueling National League pennant race and seven game World Series.”29 “The Dodgers’ ‘old men’ are tired,” noted Bob Bowie of the Pacific Stars and Stripes. “Pee Wee Reese and Jackie Robinson and Gil Hodges and Duke Snider and Roy Campanella are so weary it’s an effort for them to put one foot before another. It’s been a long season and they are anxious to get back home and relax before heading for spring training in February.”30

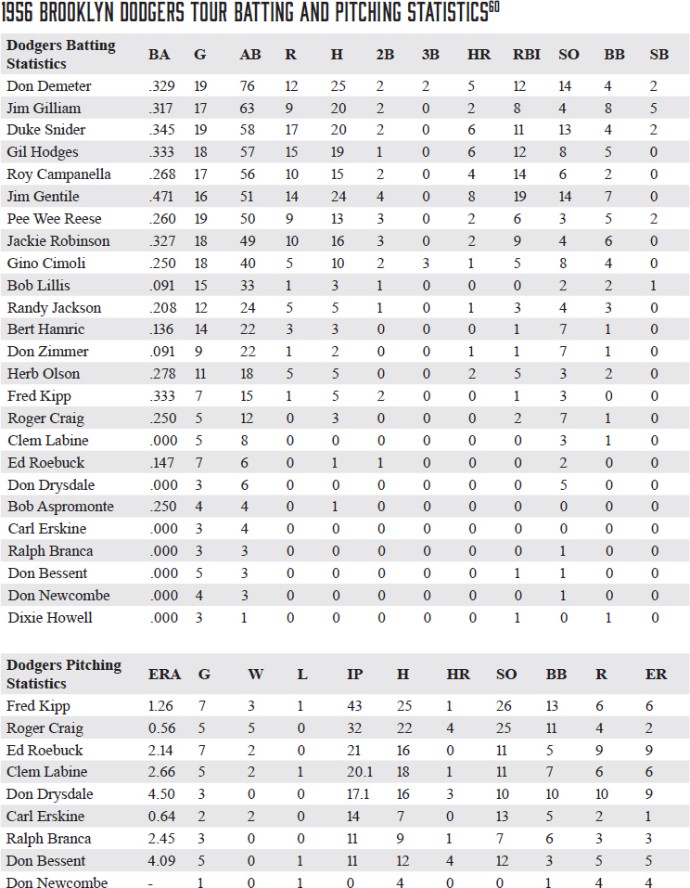

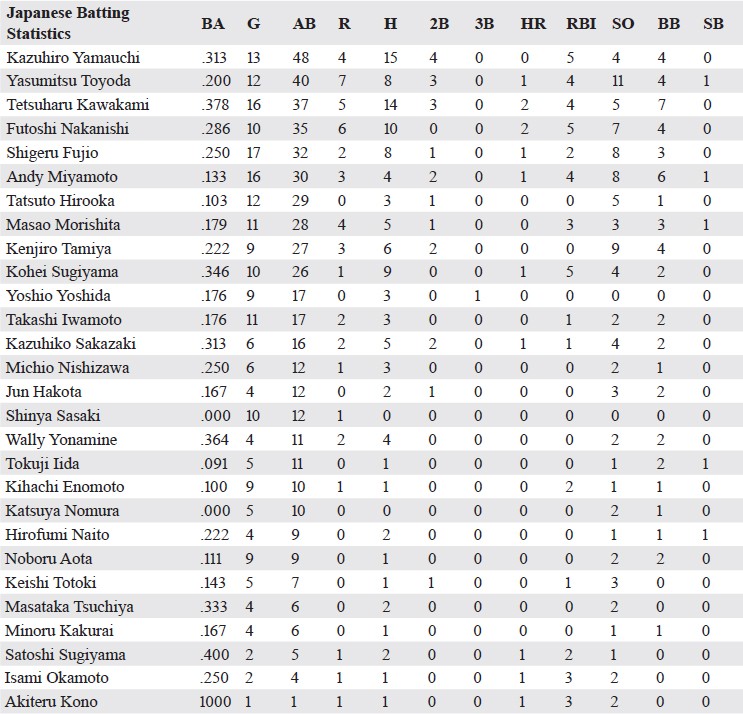

Indeed, the “Boys of Summer” were aging. The core of the team had been together nearly a decade. The starting lineup averaged 32 years old with Robinson and Reese both at 37. Their weariness showed on the playing field. After four games, the team was hitting just .227 against Japanese pitching. Both management and fans knew it was time to change, and the team had plenty of young talent. At the top of the list were power hitters Don Demeter, who hit 41 home runs in 1956 for the Texas League Fort Worth Cats, and his teammate, first baseman Jim Gentile, who hit 40. Outfielder Gino Cimoli had ridden Brooklyn’s bench in 1956 and was now ready for a more substantial role. Smooth-fielding Bob Lillis from the Triple-A affiliate in St. Paul seemed to be the heir of Pee Wee Reese at shortstop while his teammate Bert Hamric would fight for a role in team’s crowded outfield. On the mound, knuckleballer Fred Kipp hadjust won 20 games for the Montreal Royals and looked ready to join Brooklyn’s rotation. The tour of Japan was an ideal chance try out these players. As the tour progressed, Alston moved more prospects into the starting lineup.

In the fifth game, held in Sendai, Alston gave Kipp the start and backed him up with Gentile at first, Demeter in center and Cimoli in left. For seven innings Kipp baffled the All-Kanto All-Stars, a squad drawn from the Tokyo-area teams, with his knuckleball—a pitch rarely used in the Japanese leagues, while the hurler’s fellow rookies racked up five hits during an easy 8-0 win.31

Don Drysdale started game six in Mita, a small city about 60 miles northeast of Tokyo. For seven innings the promising young pitcher dominated the Japanese. Then, the Japanese erupted for three runs in the bottom of the eighth inning, breaking a streak of 29 straight shutout innings by Dodger pitching. With the scored tied, 3-3, after nine innings, the Dodgers requested that they end the game so that the team could catch their scheduled train back to Tokyo.32 Although it was not a win, an Associated Press writer called the result “a moral victory for Japanese baseball.”33 After six contests, the National League champions were 3-2-1—the worst record of any visiting American professional squad.

Despite the Dodgers’ poor start, the Japanese fans adored the team packed with household names. About 150,000 spectators attended the first five games while hundreds of thousands more, if not millions, watched the games on television or listened to them on the radio.34 “There is widespread interest in the Dodgers and their style of play,” an Associated Press article noted. All of the sports dailies and many of the mainstream newspapers covered each game in detail—often including exclusive interviews and pictorial spreads of the players. Many dailies ran “sequence shots of various Dodgers in action.”35

Although the Dodgers were winning over the Japanese fans, their opponents on the diamond were unimpressed. Ace pitcher Masaichi Kaneda noted, “The pitchers this time were not as good as [on the previous major-league tours]. … On the bench, I was looking forward to hitting. I had never had that feeling before.”36 Shortstop Yasumitsu Toyoda agreed: “Even their fastballs didn’t look fast enough.”37 Kazuhiro Yamauchi, the star outfielder for the Mainichi Orions who hit .313 in 48 at-bats during the tour, complained that the Dodgers lacked hustle. “The Yankees [during the 1955 tour] would always try for an extra base on a hit, while some Dodger runners stopped dead.”38 Yamauchi also noted that the Dodgers had trouble with low, outside pitches. “All our pitches have been aiming for the outside comer.” Yomiuri right-hander Takehiko Bessho added, “Most of them were not good at hitting curveballs. …I wasn’t [even] scared of Campanella. He looked huge, but only he could hit in one spot … the high inside corner. … If an umpire called [a low outside pitch] a strike, he complained. He was just desperate.”39

During a November 11 round-table interview moderated by Masanori Ochi, several Japanese players bristled when asked about a training session run by Dodgers coach Al Campanis. Campanis was actively promoting his book, The Dodgers’ Way to Play Baseball, which had been translated into Japanese. “We attended it, but we already knew ‘how to throw a slider,’” Tetsuharu Kawakami snidely told Ochi. “They only told us what we already knew. I think we practice small tactics more than they do.” “Al Campanis only talked about general things,” Takehiko Bessho added, “and nothing was new.”40

Oblivious to the Japanese players’ feelings, after the tour Campanis told Dan Daniels of The Sporting News, “For the good of Japanese ball, it would be well to send several American coaching staffs there for the purpose of staging clinics rather than having a different team visit each year. Of course, that wouldn’t be the sort of spectacle the fans would want, but it would be more helpful to the progress of Japanese ball. We held one clinic while we were over there, and I never had a more attentive audience. They want to learn our methods and a few clinics would help them tremendously.”41

Underwhelmed by the Dodgers, some of the Japanese players began to jeer their opponents. The Dodgers were undoubtedly unaware as the “rudeness” consisted mainly of addressing the visitors by their first names—an offensive act in Japan, especially in the mid-1950s. The players confessed during the November 11 round table interview:

Yasumitsu Toyoda: (Looking at Kaneda,) Remember you jeered at him [Newcombe] in Mito, something like ‘Come on, Don!’ He was offended by that.

Masaichi Kaneda: We became good at jeering. Our pronunciation became better.

Takehiko Bessho: You [Kaneda] were best at it. You called the first baseman [Gino] Cimoli, ‘Gino, Gino,’ and he turned and smiled at you. When the game is over, you were like ‘Goodbye Gino.’

Masaichi Kaneda: ‘Come on, Don’ was a good one!

Masanori Ochi: Did you jeer at the other major leaguers like the Yankees?

Masaichi Kaneda: No, we just did it this year.

Takehiko Bessho: That was because we were winning.

Masaichi Kaneda: Alright, I will say ‘Hey Don!’ to his face. If he gets angry, I will hide quickly!42

Undoubtedly sensing the players’ distain, Fujio Nakazawa, a commentator and future member of the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame, cautioned his countrymen. “The two victories over the Dodgers should be no reason for jubilation among the players here. They should by no means become conceited. Japanese ballplayers have much to learn from the Dodgers, who have not complained about their busy schedule which started the day after their arrival. The Dodger players are always cheerful and play hard. A defeat does not discourage them.”43

Perhaps sparked by the ongoing criticism, perhaps finally rested, the Dodgers began winning in late October as the rookies led the way. On October 27 in Kofu, Gentile hit two home runs and Demeter and Cimoli each hit one during a 12-1 romp over an allstar squad of players drawn from the Tokyo-area professional teams. The next day, Gentile went 5-for-5 with another home run as the Dodgers beat All-Japan, 6-3, in Utsunomiya.44 On October 31 Kipp pitched two-hit ball and Gentile and Demeter each homered to pace Brooklyn to a 4-2 win over All-Japan. During these games the players began showing a little fighting spirit. Somehow, they learned the Japanese word “mekura,” meaning “blind,” and began shouting it at the umpire after questionable calls.45

“Some of those ballparks were small, [holding] 20,000 or 25,000,” Carl Erskine remembers. “There were acres of bicycles in the parking lots. After the games were over, the men were all lined up along the ditch by the side of the road relieving themselves. I guess they had a couple of beers. So, it was a little unusual leaving the ballpark and passing rows and rows of men. That was a strange sight!”46

On the evening of October 31, the team arrived in Hiroshima and checked into the Hotel New Hiroshima, an ultra-modem structure near the Peace Park and ballpark. Local officials warned the players not to leave the hotel unescorted at night as gang-related crime made the area unsafe for tourists. The following morning the team visited the Peace Park and posed with their hats in their hands in front of the Memorial Cenotaph, the saddle-shaped concrete arch that bears the name of each person killed in the atomic bomb blast.

In a solemn ceremony before the start of the 2 P.M. game, the Dodgers presented city officials with a bronze plaque reading: “We dedicate this visit in memory of those baseball fans and others who died by atomic action on Aug. 6, 1945. May their souls rest in peace and with God’s help and man’s resolution peace will prevail forever, amen.”47

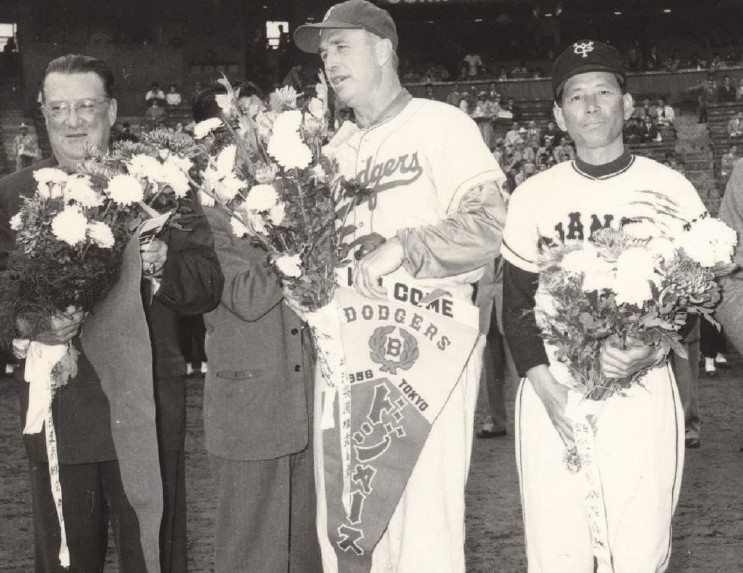

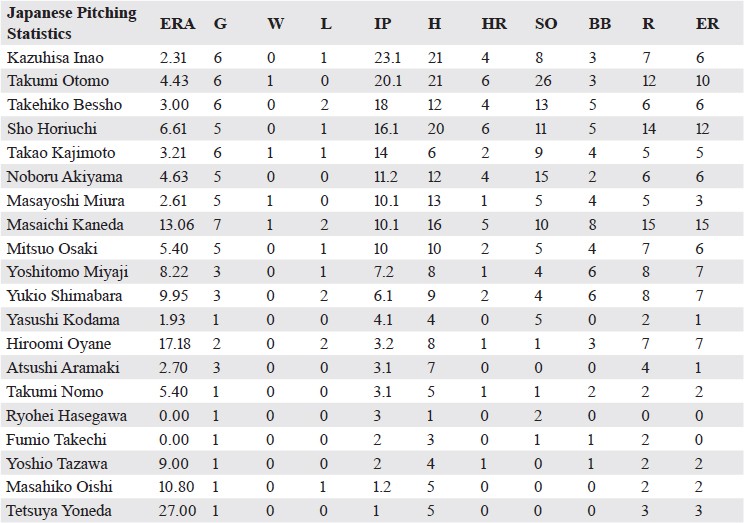

Walter O’Malley, Walt Alston, and Yomiuri Giants manager Shigeru Mizuhara. (Rob Fitts Collection)

The emotion from the morning boiled over during the game against the Kansai All-Stars. In the bottom of the third inning with the Japanese already up 1-0 and one out and a runner on second, future Hall of Fame umpire Jocko Conlon called Kohei Sugiyama safe at first on what looked to be a groundout. Incensed, Jackie Robinson walked over to first to protest the call. “Everybody knew Jocko had missed the play because he was in back of the plate and couldn’t see clearly,” Robinson explained.48 Conlon, of course, did not reverse his decision so Robinson persisted, eventually arguing “so loud and so long” that Conlon tossed him from the game. “I never told him how to play ball,” Conlon said after the game, “and he, or anybody else, can’t tell me how to run a ball game.”49

Kansai padded its lead to 4-1 before Brooklyn tied the game in the sixth on Roy Campanella’s three-run homer. The Dodgers went ahead in the seventh in a bizarre inning. After recording an out, reliever Yukio Shimabara walked Jim Gilliam, who stole second base and then moved to third on a passed ball. Shimabara then walked both Reese and Snider. With the bases loaded, Campanella fouled out to the catcher. Gilliam decided to take matters into his own hands. With two outs and the bases still jammed, he stole home to give the Dodgers the 5-4 lead. Rattled, Shimabara then made a mistake to Jim Gentile, who pounded the ball into the stands for a three-run homer. Brooklyn tacked on another two in the ninth for a 10-6 victory.50

After the Dodgers won 14-0 on November 2, the Japanese squads rebounded. On the 3rd the Dodgers and the All-Japan team entered the eighth inning knotted 7-7 before Brooklyn erupted for another seven to win 14-7. The following day, Japanese aces Takehiko Bessho and Masaichi Kaneda held the Dodgers to just one run for eight innings as the hosts entered the ninth leading 2-1. The Dodgers rallied in the ninth as Snider led off with a 480-foot home run to tie the game. Two outs later with the bases loaded, Robinson tried to steal the lead with a surprise two-out squeeze play. But Jackie missed the bunt and Demeter was tagged out on his way to the plate. In the bottom of the inning, Tetsuharu Kawakami, the hero of the opening game, came through again with a bases-loaded single to win the game.51

On the 7th the Dodgers squeaked out a 3-2 win over the All-Japan squad in Nagoya. Gil Hodges, however, stole the headlines. Alston started the normally staid first baseman in left field and to keep himself amused Hodges “pantomimed the action after almost every play for five innings. He mimicked the pitcher and the ball’s flight through the air, the catcher and the umpire. When a Dodger errored, Hodges glowered and pointed his finger. He made his legs quiver, shook his fist, stamped on the ground, swung his arms, frowned and smiled in the fleeting instant between pitches.” The fans loved it, cheering him so loudly as he left the game in the eighth inning that “[y]ou’d have thought it was Babe Ruth leaving.”52

Vin Scully recalled how Hodges’s antics eased a tense moment. “During a game before an overflow crowd, one of our players was called out on strikes and, in a childish display of petulance, dropped his bat on the plate, took off his helmet and hurled it to the ground with such force that it bounced up on top of the Dodger dugout. The crowd was shocked. The Japanese had never seen an umpire held up to such humiliation and it was an embarrassing moment for us in the Brooklyn party. Gil saved the day. While the crowd still sat in stunned silence, Gil suddenly appeared, jumped up on the dugout roof and approached the helmet as if it was a dangerous snake. He circled it warily, made a couple of tentative stabs at it, and quickly pounced on it, tossed it back on the field and then it did a swan dive off the top of the dugout. The fans beat their palms and shouted until they were hoarse.”53

The Dodgers and All-Japan met again the next day at Shizuoka, a small town at the foot of Mt. Fuji, where 22 years earlier the All-Nippon behind 17-year-old Eiji Sawamura nearly beat Babe Ruth’s All-Americans. Once again the Japanese team thrilled the fans of Shizuoka as pinch-hitter Kohei Sugiyama of the All-Japan squad broke a 2-2 tie in the bottom of the ninth with a walk-off single.54 With their fourth loss, criticism of the Dodgers’ performance continued. An International News Service article headlined, “Fans Debate Reasons for Dodger Losses” asked, “Are Japanese baseball teams improving, major leaguers getting careless or the Brooklyn Dodgers just getting old?”55

On November 9 the Dodgers returned to Tokyo for a rematch with their hosts the Yomiuri Giants. Once again, the game was tight. Home runs by Jim Gentile and Herb Olson as well as an inside-the-park homer by Giants catcher Shigeru Fujio left the score tied up after nine innings. Jim Gilliam led off the top of the 11th with a single and two outs later stood on second base as Jackie Robinson strode to the plate. Yomiuri manager Shigeru Mizuhara called for an intentional walk but Giants ace Takehiko Bessho refused. After some discussion, Mizuhara allowed Bessho to challenge Robinson. Jackie jumped on the first pitch, pounding it foul “far over the left-field stands.” On the next offering, he “drove a hot grounder through the pitcher’s box,” bringing Gilliam home to win the game.56

The win seemed to energize both the Dodgers and Robinson. They won the next two games easily, 8-2 and 10-2, as Jackie went 2-for-5 with two runs and two RBIs. After the game in Tokyo on November 12, the Dodgers flew to the southern city of Fukuoka to make up a game that had been rained out on October 30.

Fittingly, the final meeting of the 19-game series was tight. Nineteen-year-old phenom Kazuhisa Inao and Kipp dueled for eight innings, each surrendering one run. The score remained tied as Duke Snider led off the top of the ninth with a groundball to first, which the usually sure-handed Tokuji Iida muffed, allowing Snider to advance to third base. Robinson strode to the plate—unknowingly for the last time in his professional career—and grounded a single between third and short to score Snider and give the Dodgers the lead. After two outs and a walk, Don Demeter singled and Robinson crossed home plate for the final time. Immediately after the 3-1 victory, the Dodgers flew back to Tokyo and after a day of rest, returned to the United States.

Brooklyn’s tour of Japan marked the end of an era. Robinson retired soon after returning to the United States. The team’s troubles on the diamond continued in 1957 as they finished in a distant third place. It was time to rebuild. The games in Japan allowed many of the younger players to display their skills. Jim Gentile, for example, led the team with a .471 batting average, 8 home runs, and 19 RBIs, while Fred Kipp won three games and posted a 1.26 ERA in 43 innings.

Although Alston and others claimed that fatigue had led to the Dodgers’ poor showing on the diamond, they also conceded that the greatly improved Japanese had put up stiff competition. National League President Warren Giles, who accompanied the Dodgers to Japan, noted, “[T]he quality of baseball in that country is improving steadily and the day may come when the ablest players of Japan will compete on even terms with the best the United States has to offer.”57 Walter O’Malley concurred, telling reporters that the Japanese clubs would be nearly even with US ballclubs in the not-too-distant future. “Their pitchers have uncanny accuracy. They rarely walk anyone. In fielding, particularly in the infield, the Japanese teams are really excellent. Some Japanese players could play on teams in contention in pennant races here, or at least on the better minor league clubs.”58

When asked if any of the Japanese players were ready for the majors, Al Campanis responded:

There’s one fellow who must have been really good in his prime. He’s 38 years old now [actually 36] and they tell me he hasn’t hit under .300 for 18 straight years [actually eight]. I would have liked to [have] got a crack at him a few years back. His name is Kawakami. … High in my book were three others. A shortstop named Toyoda … was the best hitter in his league. His arm might have been a little short, but he had everything else. Then there was a catcher, Fujio, in his first year of pro ball. Never saw anyone with a better arm. Man, he had a rifle. Good receiver, too, and a fair hitter. But the number one prospect in my judgment was a pitcher named Sho Horiuchi, a 21-year-old right hander with the Yomiuri Giants.59

The following spring, the Dodgers invited Fujio and Horiuchi along with their manager Shigeru Mizuhara, to spring training at Dodgertown to help them mature as players. The invitation began a long friendship between the two clubs. The Giants would be the Dodgers’ guests at Vero Beach in 1961, 1967, 1971, and 1975 and the two clubs would maintain close relations for over 65 years.

ROBERT K. FITTS is the author of numerous articles and seven books on Japanese baseball and Japanese baseball cards. Fitts is the founder of SABR’s Asian Baseball Committee and a recipient of the society’s 2013 Seymour Medal for Best Baseball Book of 2012; the 2019 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award; the 2012 Doug Pappas Award for best oral research presentation at the annual convention; and the 2006 and 2021 SABR Research Awards. He has twice been a finalist for the Casey Award and has received two silver medals at the Independent Publisher Book Awards. While living in Tokyo in 1993-94, Fitts began collecting Japanese baseball cards and now runs Robs Japanese Cards LLC. Information on Rob’s work is available at RobFitts.com.

NOTES

1 “All Dodgers’ O’Malley Gets Is Ride,” New York Daily News, October 13, 1956: 36.

2 “Dodgers Invited to Tour Japan in Fall; Most Favor Trip, but Furillo Votes No,” New York Times, May 2, 1956: S36.

3 Ed Wilks, Newcombe ‘Gets Lost’ After Humiliation,” Monroe (Louisiana) News-Star, October 11, 1956: 12.

4 United Press, “Dodgers Arrive at 5:30 P.M. Today,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 12, 1956: 14; Carl Lundquist, “Flatbushers Full of Frolic as They Leave For Japan,” The Sporting News, October 17, 1956: 13.

5 Tom Hopkins, “Sportraitures,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 18, 1956: 38; Red McQueen, “Dodgers Outdraw Yankees,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 16, 1956: 14.

6 Associated Press, “Bums Arrive in Tokyo,” Passaic (New Jersey) Herald-News, October 18, 1956: 46.

7 United Press, “Japanese Fans Defy Rain to Hail Dodgers,” New York Daily News, October 19, 1956: 155.

8 Vin Scully, “The Dodgers in Japan,” Sport, April 1957: 92; Bob Bowie, “Actresses, Flowers, Cheers Welcome Tourists to Tokyo,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1956: 9.

9 Scully.

10 “Bums Open Game with Giants Today,” Japan Times, October 19, 1956: 5.

11 Scully.

12 Leslie Nakashima, “Dodgers Beaten 5-4 by Yomiuri Giants in Japan,” Honolulu Advertiser October 20, 1956: 14.

13 >Other victories came in 1922, 1951, 1953 against the Eddie Lopat All-Stars, and 1953 against the New York Giants. The Royal Giants’ tours are excluded from these figures as not all of their results are known.

14 Mel Derrick, “Alston Explains: ‘They Hit, and We Didn’t,’” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 20, 1956: 23.

15 Bob Bowie, “Dodgers Belt Central Loop Stars 7-1,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 21, 1956: 24.

16 Mel Derrick, “Newcombe a Study in Dejection After Loss,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 22, 1956: 24.

17 Bob Bowie, “All-Stars Rout Brooks 6-1,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 22, 1956: 24; Derrick, “Newcombe a Study,” 24.

18 Derrick.

19 Derrick.

20 Bowie, “All-Stars Rout Brooks 6-1.”

21 United Press, “Dodgers’ Good Behavior Mystifies Japanese Fan,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 26, 1956: 14.

22 Associated Press, “Japanese Can Learn from Bums,” Hawaii Tribune-Herald (Hilo, Hawaii), October 23, 1956: 7.

23 United Press, “Banzais Changed to Brickbats for Dodgers on Japanese Tour,” New York Times, October 23, 1956: 42.

24 United Press, “Japanese Baseball Expert Hints Brooks Are Bums,” New York Daily News, October 23, 1956: 124.

25 United Press, “Bums ‘Too Dignified,’ Say Japanese Hosts,” New York Daily News, October 26, 1956: 125.

26 Carl Erskine, telephone interview with author, February 10, 2020.

27 Carl Erskine, Tales from the Dodger Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2000), 65.

28 United Press, “Brooks Nip Giants 1-0 on Snider’s Home Run,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 24, 1956: 24.

29 Associated Press, “Japanese Can Learn from Bums,” Hawaii Tribune-Herald, October 23, 1956: 7.

30 Bob Bowie, “Newk’s Tribulations,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 24, 1956: 22.

31 “Brooks Whitewash All-Kanto Nine, 8-0,” Japan Times, October 25, 1956: 8.

32 Associated Press, “Kanto All-Stars Tie Dodgers 3-3,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 27, 1956: 24.

33 Associated Press, “Kanto All-Stars Tie Dodgers 3-3.”

34 Bob Bowie, “Gates Spin as Bums Battle for Wins in Japan,” Sporting News, October 31, 1956: 7.

35 Associated Press, “Japanese Can Learn from Bums.”

36 “A Round Table Talk,” Baseball Magazine, 11, no. 12 (December 1956): 76-83.

37 “A Round Table Talk.”

38 Associated Press, “Yankees Showed More Hustle Than Dodgers,” Honolulu Star Bulletin, November 14, 1956: 44.

39 “A Round Table Talk.”

40 “A Round Table Talk.”

41 Dan Daniel, “Over the Fence,” The Sporting News, November 28, 1956: 12.

42 “A Round Table Talk.”

43 United Press, “Japanese Warned against ‘Conceit,’” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 28, 1956: 20.

44 Although English-language sources list Gentile going 4 for 4, official Japanese sources have him at 5 for 5.

45 >Associated Press, “Japan’s Pitchers Surprise Brooks,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 30, 1956: 19.

46 Erskine, telephone interview.

47 Associated Press, “Dodgers to Dedicate Game to Bomb Victims,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 29, 1956: 24.

48 “Dodgersvs. Kansai All Stars at Hiroshima Stadium, Hiroshima—November 1, 1956,” walteromalley.com. https://www.walteromalley.com/en/dodger-history/international-relations/1956-Summary_November-1-1956. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

49 “Jackie Drops Verbal Bomb at Hiroshima—Gets Thumb,” The Sporting News, November 14, 1956: 4.

50 Hochi Sports, November 2, 1956: 2; “Dodgers vs. Kansai,” United Press, “Dodgers Top Kansai, 10-6; Robby Chased,” New York Daily News, November 2, 1956: 175.

51 Associated Press, “Bums Win 14-7 Before 60,000,” Honolulu StarBulletin, November 3, 1956: 11; Associated Press, “Labine of Dodgers Loses in Japan, 3-2,” New York Times, November 5, 1956: 44.

52 Associated Press, “Hodges Delights Fans with Baseball Performance,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 8, 1956: 22.

53 Scully.

54 United Press, “Dodgers Downed by Japanese, 3-2,” New York Times, November 9, 1956: 37.

55 International News Service, “Fans Debate Reasons for Dodger Losses,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 8, 1956: 19.

56 United Press, “Dodgers Edge Tokyo Giants 5-4,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 10, 1956: 24.

57 Tom Swope, “‘Japanese Players Gaining Major Status Fast’—Giles,” The Sporting News, November 21, 1956: 2.

58 United Press, “O’Malley Praises Japanese Baseball,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 30, 1956: 24.

59 Daniel.

60 Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs, U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 92; Nippon Professional Baseball Records, https://www.2689web.com/nb.html; “Dodgers Individual Batting Results,” Baseball Magazine, 11, no. 12 (December 1956): 64.