Returning Home: The 1914 Seattle Nippon and Asahi Japanese American Tours

This article was written by Rob Fitts

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

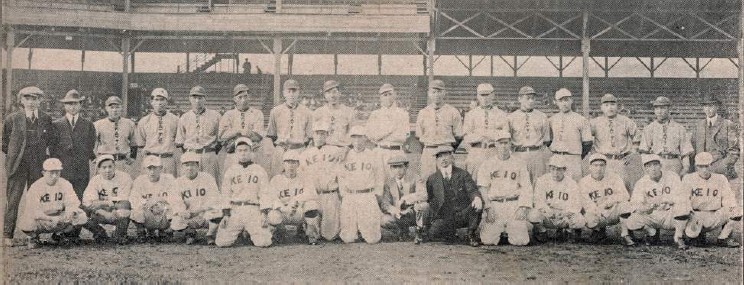

Seattle Nippon and Keio University in 1914. (Rob Fitts Collection)

INTRODUCTION

Between 1890 and 1910, over 100,000 Japanese immigrated to the West Coast of the United States. Many settled in the urban centers of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle. Within a few years, each of these immigrant communities had thriving baseball clubs. The first known Japanese American team was the Fuji Athletic Club, founded in San Francisco around 1903. A second Bay Area team, the Kanagawa Doshi Club, was created the following year. That same year, newsmen at the Rafu Shimpo organized Los Angeles’s first Issei (Japanese immigrant) team. Other clubs followed in the wake of Waseda University’s 1905 baseball tour of the West Coast. Many players learned the game while still in Japan at their high schools or colleges. Others picked up the sport in the United States. The first Japanese professional club was created the following year by Guy Green of Lincoln, Nebraska. His Green’s Japanese Base Ball Team, consisting of Japanese immigrants from Los Angeles, barnstormed throughout the Midwest in the spring and summer of 1906.

Seattle’s first Japanese American club, called the Nippon, was also organized in 1906. Shigeru Ozawa, one of the founding players, recalled that the team was not very good at first and was able to play only the second-tier White amateur nines. By 1907 the team had a large local following. In its first appearance in the city’s mainstream newspapers, the Seattle Star noted that “before one of the largest crowds seen at Woodlands park the D.S. Johnstons defeated the Nippons, the fast local Jap team, by a score of 11 to 5.”1 In May 1908, before a game against the crew of the USS Milwaukee, the Seattle Daily Times reported that the Nippon “have picked up the fine points of the great national game rapidly from playing the amateur teams around here every Sunday.”2

Two months later, the Daily Times featured the team when it took on the all-female Merry Widows. Mistakenly referring to the Nippons as “the only Japanese baseball club in America,” the newspaper reported, “when these sons of Nippon went up against the daughters of Columbia, viz., the Merry Widow Baseball Club, it is a safe assumption that the game played at Athletic Park yesterday afternoon was the most unique affair in the annals of the national game.”3 Over a thousand fans, including many Japanese, watched the Nippons win, 14-8.

Soon after the game with the Merry Widows, second baseman Tokichi “Frank” Fukuda and several other players left the Nippon and created a team called the Mikado. The Mikado soon rivaled the Nippons as the city’s top Japanese team, with the Seattle Star calling them “one of the fastest amateur teams in the city.”4 In both 1910 and 1911, the Mikado topped the Nippon and Tacoma’s Columbians to win the Northwest Coast’s Nippon Baseball Championship.5

As Fukuda’s love for baseball grew, he realized the game’s importance for Seattle’s Japanese. The games brought the immigrants together physically and provided a shared interest to help strengthen community ties. It also acted as a bridge between the city’s Japanese and non-Japanese population, showing a common bond that he hoped would undermine the anti-Japanese bigotry in the city.

In 1909 Fukuda created a youth baseball team called the Cherry—the West Coast’s first Nisei (Japanese born outside of Japan) squad. Under Fukuda’s guidance, the club was more than just a baseball team. Katsuji Nakamura, one of the early members, explained in 1918, “The purpose of this club was to contact American people and understand each other through various activities. We think it is indispensable for us. Because there are still a lot of Japanese people who cannot understand English in spite of the fact that they live in an English-speaking country. That often causes various troubles between Japanese and Americans because of simple misunderstandings. To solve that issue, it has become necessary that we, American-born Japanese who were educated in English, have to lead Japanese people in the right direction in the future. We have been working the last ten years, according to this doctrine.”6

As the boys matured, the team became stronger on the diamond and in 1912 the top players joined with Fukuda and his Mikado teammates Katsuji Nakamura, Shuji “John” Ikeda, and Yoshiaki Marumo to form a new team known as the Asahi. Like the Cherry, the Asahi was also a social club designed to create the future leaders of Seattle’s Japanese community, and forge ties with non-Japanese through various activities, including baseball.7 Once again the new club soon rivaled the Nippon as Seattle’s top Japanese American team.

THE NIPPON TOUR

During the winter of 1913-14, Mitomi “Frank” Miyasaka, the captain of the Nippon, announced that he was going to take his team to Japan, thereby becoming the first Japanese American ballclub to tour their homeland. To build the best possible squad, Miyasaka recruited some of the West Coast’s top Issei players. From San Francisco, he recruited second baseman Masashi “Taki” Takimoto. From Los Angeles, Miyasaka brought over 30-year-old Kiichi “Onitei” Suzuki. Suzuki had played for Waseda University’s reserve team before immigrating to California in 1906. A year later, he joined Los Angeles’s Japanese American team, the Nanka. He also founded the Hollywood Sakura in 1908. In 1911 Suzuki joined the professional Japanese Base Ball Association and spent the season barnstorming across the Midwest. Miyasaka’s big coup, however, was Suzuki’s barnstorming teammate Ken Kitsuse. Recognized as the best Issei ballplayer on the West Coast, in 1906 Kitsuse had played shortstop for Guy Green’s Japanese Base Ball Team, the first professional Japanese club on either side of the Pacific. He was the star of the Nanka before playing shortstop for the Japanese Base Ball Association barnstorming team in 1911. Throughout his career, Kitsuse drew accolades for his slick fielding, blinding speed, and heady play.

To train the Nippons in the finer points of the game, Miyasaka hired 38-year-old George Engel (a.k.a. Engle) as a manager-coach. Although Engel had never made the majors, he had spent 14 seasons in the minor leagues, mostly in the Western and Northwest Leagues, as a pitcher and utility player. Miyasaka also created a challenging schedule to ready his team for the tour. They began their season with games against the area’s two professional teams from the Northwest League. On Sunday, March 22, they lost, 5-1, to the Tacoma Tigers, led by player-manager and future Hall of Famer Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity. The following Sunday the Seattle Giants, which boasted seven past or future major leaguers on the roster, beat them 5-1. Despite the one-sided loss, the Seattle Daily Times noted, “the Nippons … walked off Dugdale Field yesterday afternoon feeling well satisfied with themselves for they had tackled a professional team and had made a run.”8

In April 1914, Keio University returned for its second tour of North America. After dropping two games in Vancouver, British Columbia and a third to the University of Washington, Keio met the Nippons on April 9 at Dugdale Park in what the Seattle Daily Times called “the world’s series for the baseball championship of Japan.”9 On the mound for Keio was the great Kazuma Sugase, the half-German “Christy Mathewson of Japan,” who had starred during the school’s 1911 tour. The team also included future Japanese Hall of Famers Daisuke Miyake, who would manage the All-Nippon team against Babe Ruth’s All-Americans in 1934, and Hisashi Koshimoto, a Hawaiian-born Nisei who would later manage Keio.

Nippons manager George Engel was in a quandary. His usual ace Sadaye Takano was not available and as Keio would host his team during its coming tour of Japan, he needed the Nippons to prove they could challenge the top Japanese college squad. Engel reached out to William “Chief’ Cadreau, a Native American who had pitched for Spokane and Vancouver in the Northwestern League, one game for the 1910 Chicago White Sox, and would later pitch a season for the African American Chicago Union Giants.10 Pretending that he was a Japanese named Kato, Cadreau started the game. According to the Seattle Star, “Engel was very careful to let the Keio boys know that Kato, his pitcher, was deaf and dumb. But later in the game Kato became enthused, as ball players will, and the jig was up when he began to root in good English.”11 Nonetheless, Cadreau handled Keio relatively easily, striking out 13 en route to a 6-3 victory.12

Throughout the spring and summer, the Nippons continued to face the area’s top teams, including the African American Keystone Giants, to prepare for the trip to Japan. Yet in their minds, the most important matchup was the three-game series against the Asahi for the Japanese championship. The Nippons took the first game, 4-2, on July 12 at Dugdale Park but there is no evidence that they finished the series.13 Not to be outdone by their rivals, the Asahi also announced that they would tour Japan later that year. Sponsored by the Nichi-nichi and Mainichi newspapers, the Asahi would begin their trip about a month after the Nippons left for Japan.

The Nippon left Seattle aboard the Shidzuoka Maru on August 25.14 Their departure went unreported by the city’s newspapers as international news took precedence. Germany had invaded Belgium on August 4, opening the Western Front theater of World War I. Throughout the month, Belgian, French, and British troops battled the advancing Germans. Just days before the ballclub left for Japan, the armies clashed at Charleroi, Mons, and Namur with tens of thousands of casualties. On August 23, Japan declared war on Germany and two days later declared war on Austria.

After two weeks at sea, the Nippon arrived at Yokohama on September 10.15 The squad contained 11 players: George Engel, Frank Miyasaka, Yukichi Annoki, Kyuye Kamijyo, Masataro Kimura, Ken Kitsuse, Mitsugi Koyama, Yohizo Shimada, Kiichi Suzuki, Sadaye Takano, and Masashi Takimoto. Accompanying the ballplayers was the team’s cheering group, consisting of 21 members and led by Yasukazu Kato. The group planned to attend the games to cheer on the Nippon and spend the rest of their time sightseeing.

As the Shidzuoka Maru docked, a group of reporters, Ryozo Hiranuma of Keio University, Tajima of Meiji University, and a few university players came on board to welcome the visiting team. The group then took a train to Shinbashi Station in Tokyo, where they were met by the Keio University ballplayers at 2:33 P.M. The Nippon checked in at the Kasuga Ryokan in Kayabacho while the large cheering group, which needed two inns to accommodate them, settled down at the Taisei-ya and Sanuki-ya.16

Only two hours later, the Nippon arrived at Hibiya Park for practice. Not surprisingly, after the voyage they were not in top form. The Tokyo Asahi noted, “Even though the Seattle team is composed of Japanese, their ball-handling skills are as good as American players, and … their agile movements are very encouraging. … They hit the ball with a very free form, but yesterday, they did not place their hits very accurately, most likely due to fatigue. … The Seattle team did not have a full-fledged defensive practice with each player in position, so we did not know how skilled they were in defensive coordination, but we heard that the individual skills of each player were as good as those of Waseda and Keio. In short, the Seattle team has beaten Keio University before, so even though they are Japanese, they should not be underestimated. On top of that, they have good pitching, so games against Waseda University and Keio University are expected to arouse more than a few people’s interest, just like the games against foreign teams in the past.”17

The Nippon would stay in Japan for almost four months, but the baseball tour itself consisted of just eight games—all played during September against Waseda and Keio Universities. The players spent the rest of the time traveling through their homeland and visiting family and friends.

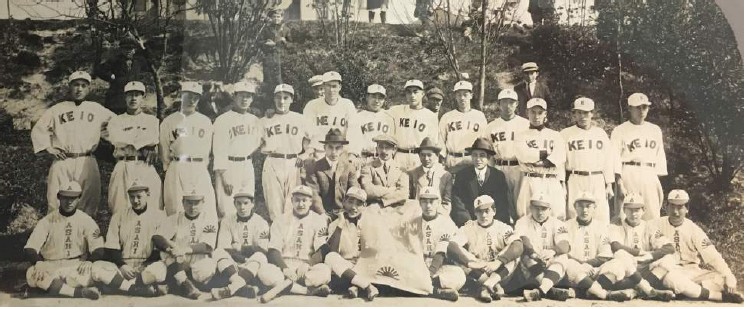

Seattle Asahi and Keio University in 1914. (Rob Fitts Collection)

The Nippon opened their tour on September 12 against Waseda at the university’s Totsuka Grounds. “It was a clear, crisp autumn day and a perfect day for baseball, and the crowd was very happy to see them. At 1:30 P.M. the Waseda University team entered, and at the same time the Seattle team entered in their vertical striped uniforms. [Tokyo] mayor [Yoshiro] Sakatani appeared in a dashing suit with a smile on his face, climbed up to the mound and threw the first pitch.”18

Engel decided not to let Sadaye Takano, his usual starting pitcher, face the Japanese colleges. Instead, Engel took the mound himself, although he had not pitched professionally for two years. In his final season with Vancouver of the Northwestern League, he went 7-4 in 87 innings. Now, at 39 years old, he faced a tough Waseda lineup.

The enthusiastic crowd was treated to a tight game of small ball. In the top of the first, Seattle’s “Taki” Takimoto eked out a two-out walk but was thrown out trying to steal second. In the bottom half of the inning, leadoff batter Kichibei Kato walked. Engel bore down and struck out Kazuyoshi Yokoyama. As the umpire called strike three, catcher Yohizo Shimada fired the ball to first, trying to catch a napping Kato off the bag. But the throw got away, and Kato circled the bases for the first run as the Nippon players chased down the rolling ball.

Over the next three innings, both Engel and Waseda starter Tamizo Kawashima no-hit their opponents. In the bottom of the fifth, Waseda scored twice on a walk, a single, an error, and a squeeze play to lead, 3-0. Seattle struck back in the sixth as Miyasaka tripled and scored on a single by Yukichi Annoki. In the seventh, Seattle scored three more to take a 4-3 lead. Waseda seemed “stunned and helpless” as the Nippon “desperately tried to control the remaining two innings.”19 But they could not. In the bottom of the eighth, Kawashima reached base on an error, stole second, and scored on consecutive hits by Kato and Yokoyama to knot the score.

Ken Kitsuse led off the ninth inning with a walk, moved to second on a sacrifice, and streaked to third on a fly out to center field. With two outs and the go- ahead run at third, Kawashima battled with Nippon center fielder Annoki. Kawashima prevailed, striking out Annoki, but Waseda catcher Tadao Ichioka dropped the third strike and threw wildly to first as Kitsuse scampered home. Engel pitched a scoreless ninth to preserve the 5-4 victory.

The three-game series against Keio University began on September 15 at the Mita grounds. Engel started on the mound for Seattle against their ace, Kazuma Sugase. After their loss to the Nippon in Seattle, the collegians were looking for revenge and they played aggressive ball from the first pitch.20 Keio center fielder Jinkichi Kaji began the game with a bunt hit down the third-base line. Shigeki Mori then singled, and Daisuke Miyake beat out a bunt to load the bases with no outs. Engel then got cleanup hitter Akira Kusaka to hit a weak grounder back to the mound. Engel threw home for the first out but the catcher’s throw to first base was dropped and Mori scored. The next batter, Shigeru Takahama, also grounded back to the pitcher. Engel threw to second for the out, and Takimoto threw to first to complete the double play, but first baseman Frank Miyasaka once again dropped the ball as Miyake scored. A single by Shungo Abe knocked in another to give Keio a 3-0 lead. “It looked like the game was already decided.”21 Keio went on to score four more times as Sugase shut out the Nippon on just four hits and did not allow a runner to get to second base in the 7-0 win. An observer noted, “The Seattle team looked really listless, completely lackluster, as if they had been debilitated by the bad plays in the first and second innings.”22

Four days later, on September 19, Nippon had a chance to redeem themselves in the second game against Keio. Engel pitched again for Seattle but Keio started Hisao Numata. This time Seattle jumped out to an early lead, scoring once in the second and three in the fourth as they knocked out Numata. Engel, meanwhile, pitched brilliantly, allowing just three hits through seven innings.

In the eighth inning, however, Seattle’s defense nearly betrayed them again. With one out, Unosuke Hirai hit a routine fly ball to left field. Kiichi Suzuki, playing shallow, misjudged it and it flew over his head for a double. Sugase (who came in to relieve Numata) then tripled to score Hirai. After Kaji grounded out to the pitcher, Mori hit a fly ball to left that should have ended the inning, but the ball popped out of Suzuki’s glove and Sugase scored. The Nippon immediately appealed, arguing that Suzuki had successfully made the catch before the ball came loose. The umpire, however, disagreed and allowed the run to count. In disgust, Takimoto marched off the field. Unused to such poor sportsmanship, the fans were “very critical” of Takimoto’s behavior.23 A subsequent error by shortstop Kimura allowed Mori to score and reduce Seattle’s lead to one run, before Engel struck out Takahama to end Keio’s last threat of the game.24 After the 4-3 Nippon victory, the press praised Engel. The “39-year-old veteran pitcher showed off his strong arm again and fought hard for the Seattle team, his energy was unmatched by any of the younger players on the Seattle team. Keio’s hitters were tormented.”25

On September 20 at 2:30 P.M. the Nippon faced Waseda for the second time. Having pitched a complete game the day before, Engle decided to start Sadaye Takano. It did not go well. Waseda tagged Takano for three runs in the second inning. Engel quickly pulled Takano and brought in second baseman Takimoto to pitch. He did worse—surrendering another three before getting the third out and then giving up seven runs in the third inning. By the end of the game, Waseda had pounded out 23 runs on 16 hits with 10 walks against four pitchers as the porous Seattle defense committed 10 errors. Meanwhile, Waseda starter Tamizo Kawashima stifled the Nippon by allowing just four hits and two runs.26

Two days later Seattle took on the Waseda alumni Tomon Club. An article in the annual Yakyu-Nenpoh noted that “the Tomon players, although aging, are all fierce fighters who once enjoyed fame.” The starting lineup included future Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame members Shin Hashido, Kiyoshi Oshikawa, and Chujun Tobita. Engel, once again, took the day off and started Yohizo Shimada on the mound. The game began ominously for Seattle. After a leadoff walk to Kimura, followed by an infield hit by Koyama, third batter Takimoto hit the ball back to the pitcher. The pitcher caught the ball on the fly, and immediately threw to first to catch Koyama straying off first. Then the first baseman quickly threw to second to nab Kimura before he could return to the base: triple play. The “stunned” Nippon’s concentration and defense fell apart.27 Seattle made seven errors, nearly all at key moments, as Tomon coasted to an easy 15-3 victory.

Engel returned to the mound for the third and deciding game against Waseda on September 26. The Nippon started well as two-out hits by Kimura, Miyasaka, and Shimada loaded the bases with Takimoto up. With two balls on Takimoto, Waseda pitcher Kawashima threw ball three. Kimura, having lost count of the balls and thinking Takimoto had walked, ambled home, only to be tagged out to end the inning. The rest of the game was tight. Waseda moved ahead with a run in the first and two in the third, only to see its lead evaporate with a three-run Seattle fourth. The collegians retaliated with two runs in the bottom of the fifth to lead 5-3. In the seventh the Nippon tied the game again, with two runs on a triple, a groundout, and a single, followed by two Waseda errors. But once again, the visitors’ comeback was short-lived. In the bottom of the seventh, Waseda scored three on two triples, a hit batsman, and a squeeze bunt. Kawashima pitched no-hit ball in the final two innings to preserve the Waseda 8-5 victory.28

The deciding game against Keio on September 27 was the highlight of the tour. To the delight of the fans at Mita Tsunamachi Field, both teams battled in a “fierce game.”29 Despite having pitched a complete game the previous day against Waseda, Engel took the mound. Once again, their ace Kazuma Sugase started for Keio. Umpiring the game were two future Hall of Famers Nenosuke Fukuda and Chujun Tobita. Both men later changed U.S.-Japan baseball relations by playing important roles in the two greatest upsets during the pre-World War II tours.

Engel and Sugase both pitched brilliantly. At the end of nine innings, each pitcher had surrendered just two hits and held the opposition scoreless. The pitchers’ duel and shutouts continued into the 12th inning as the teams “battled desperately.”30 In the bottom half of the inning, Sugase reached first with one out on a fielder’s choice. Akira Kusaka then slashed a grounder that “slipped passed [sic] [second baseman] Takimoto’s right hand, allowing Sugase to advance to third and Kusaka to second.” The next batter, Yoichi Togashi, hit a hard line drive at right fielder Frank Miyasaka. Miyasaka, who usually played first base, “panicked” and fumbled the ball, allowing Sugase to score the winning run.31

After losing both of the three-game series against Waseda and Keio, Nippon finished out their tour on September 28 with a game against the Mita Club—Keio’s alumni team. Having pitched 21 innings in the past two days, Engel allowed Takano to start the game. For five innings Takano pitched well, shutting out Mita on just two hits as his teammates scored six runs off Mita starter Nenosuke Fukuda (the umpire from the previous day’s game). In the sixth inning, the game fell apart for Seattle. With four hits and a Nippon error, Mita scored four times, knocking out Takano. Annoki took over the mound, quelled Mita’s rally, and shut down the opposition for two more innings. But in the bottom of the ninth, Mita scored twice to tie the game and send it into extra innings. Neither team scored in the 10th as a haze settled over the ballpark, darkening the sky. After the inning, the teams agreed that it was too difficult to see, and the game ended in a 6-6 tie.32

Engel left for Seattle soon after the Mita game but most of his teammates stayed in Japan until February. For Ken Kitsuse the trip was highly productive. He left Japan with a bride, marrying 16-year-old Suye Hoshiyama on November 30 in Tokyo.33

Back home, Engel explained away the Nippon’s disappointing 2-5-1 record. “George has many tales to tell about the ‘Land of the Rising Sun,’ some of which are on the hard luck order,” reported the Seattle Daily Times, noting that “some of their losses were by small scores.” Nevertheless, Engel praised his Japanese hosts. He “speaks very highly of the treatment received by the local lads in Japan. The Keio and Waseda baseball nines, both of which visited the United States last year, have shown marked improvement in their play. … Engle [sic] has in his possession a whole truckload of autographed bats and balls and the usual amount of Oriental souvenirs. The best story told by George on his return, however, is that his trusty right wing, which used to mow down the Northwestern League batters in order, has once more its former strength, and he proudly announces that more will be heard from the rejuvenated wing in the future. George’s ‘comeback’ stock is accompanied by the announcement that he will personally conduct a tour of the Orient with the Northwestern League champions next year, if arrangements can possibly be made.”34 This tour, however, never materialized.

THE ASAHI TOUR

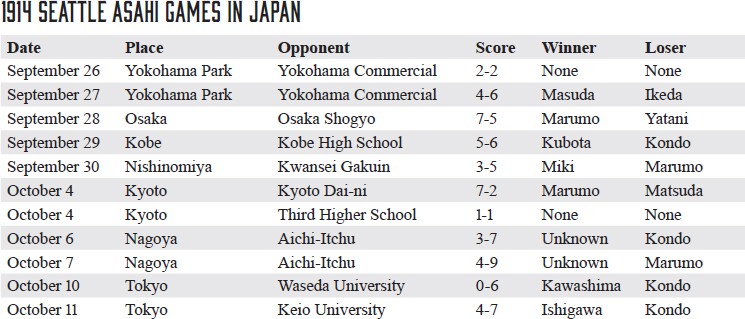

As the Seattle Nippon were finishing up their games, Frank Fukuda and his Asahi team arrived in Yokohama on the afternoon of September 24, 1914. Led by Fukuda and manager Katsuji Nakamura, the team consisted of nine additional players between 17 and 29 years old: Junji Aisawa, Shinji “John” Ikeda, Hidekichi Kobayashi, Sukehiko “James” Kondo, Shirajiro Kouchi, Yoshiaki Marumo, Tako Osawa, Fukuo Sano, and Masao Yasuda.35 Fukuda played second base for the squad.

For Frank Fukuda, the trip to the home country was about more than baseball. He “thought that seeing and understanding their old country was indispensable for his Nisei players to become better citizens and to establish a better Japanese community in Seattle.”36 Following the concept of kekehashi (literally “bridge” but in this case a bridge of understanding), Fukuda felt that an understanding of both Japanese and American values could prepare his players to become civic leaders capable of bridging the cultural gaps between Issei and Nisei as well as Japanese Americans and greater American society. Ideally this cultural bridge would reduce misunderstandings and bigotry, ultimately allowing Japanese to assimilate into American society while still maintaining their distinctive traditions.37 Speaking at Keio University several years later, manager Nakamura explained:

“All members here have really wanted to visit Japan. We have dreamed of meeting the people who have the same blood as ours. Now our dreams came true. It is impossible to express how delighted we are. One of the reasons for our tour is to observe Japanese society and economy, but the most important objective is to learn Yamato damashii [Japanese spirit] in order to become a Japanized American—bom Japanese, rather than become an Americanized Japanese. And if we do something in American style with the Japanese way of thinking, we believe we can produce a superior combination of those two cultures.”38

The day before the Asahi arrived, the Yokohama Boeki Shimpo ran an article entitled, “Welcome Asahi Players!” noting that “they are called the Seattle Asahi Study Group” and “they came for sightseeing, discovering their mother country, and to study.” “Because they were bom in the United States,” the article continued, “they have heard about Japan and imagined it, but this is the first time they will take steps on the mother country. We should imagine their excitement and joy [and] we should welcome them with courtesy.”39

A welcoming committee led by Ryozo Hiranuma and the staff of the Yokohama Boeki Shimpo met the players at the dock. The next day as the players acclimated to their new surroundings, the Yokohama Elementary School welcomed them to Japan with a speech in English.40

The baseball tour opened against Yokohama Commercial High School at Yokohama Park Field on September 26. The high school had one of the top teams in the Tokyo area, routinely playing against Waseda and Keio Universities as well as visiting American teams. After Yokohama Commercial’s principal, Susumu Misawa, threw the first ball at 3:30, James Kondo took the mound for Asahi. The game was a thrilling but ugly affair, marred by 12 errors and 10 walks. Both pitchers wormed out of trouble several times as the clubs entered the eighth inning tied, 2-2. By then dusk had fallen. The players struggled through the inning before declaring the game a tie in the top of the ninth due to darkness.

The teams met again the next day. It was another tight game as the Asahi surged ahead in the first inning with two runs, but Yokohama tied the score with runs in the third and fourth before going ahead, 3-2, in the seventh without a hit as a muffed grounder followed by a wild pickoff attempt brought in a run. In the bottom of the eighth, Asahi evened the score to set up an exciting final inning. Yokohama thrilled its fans by erupting for three runs in the top of the inning before holding off a bottom-of-the-ninth Asahi rally to win, 6-4.

Immediately after the game, the Asahi players left for Osaka, where they would play the Kansai champion, Osaka Shogyo, the following day.41 Once again, a close game was ended early due to darkness. Asahi led 7-5 in the eighth inning when the teams agreed to end play. The following afternoon, September 29, Asahi took on Kobe High School (home to future alumnus, writer Haruki Murakami). In another hard-fought game, Asahi lost, 6-5. The travelers next went to the neighboring city of Nishinomiya, where they played Kwansei Gakuin, a private nondenominational Christian university founded in 1889 by the American missionary Walter Russell Lambuth. The collegians had little trouble with the visiting amateurs, holding the Asahi to just two hits as they won comfortably, 5-3.

The Asahi then traveled northeast to the ancient capital of Kyoto, where they spent several days touring cultural sites. They visited the famed Golden Pavilion and Kiyomizu Temple as photographers for Yakyukai magazine clicked away.42 On the morning of October 4, Asahi overwhelmed Kyoto Dai-ni Chugaku (Kyoto Second High School) in a sloppy display of small-ball tactics. Kyoto held Seattle to just one hit, but the Asahi took advantage of six walks and four errors to steal 10 bases and score seven runs. Asahi’s defense was also porous; they committed six errors and surrendered four walks. But nonetheless, they held the high schoolers to just two runs to gain the victory. The following summer, the Kyoto high schoolers went on to win the inaugural national high-school championship tournament at Koshien.

Later that afternoon, the Asahi played their final game in Kyoto, against the Third Higher High School, commonly known as Sanko. Usually a strong team, Sanko had just finalized its roster for the coming season and many local fans came to the ball grounds to see the new players in action. The spectators were treated to a tight pitchers’ duel. Asahi starter Kondo held his opponents to just three hits and a single unearned run, but Sanko’s starter Yokochi did even better, striking out nine and not allowing a hit for the first seven innings. The high schoolers entered the eighth inning with a 1-0 lead when Asahi outfielder Junji Aisawa reached second on an error and then scored on Seattle’s first and only hit of the afternoon. The game ended as a 1-1 draw.

Fukuda and his team were probably pleased with the results so far. They had played well against five top high schools and one college, winning two, losing three, and tying two. As they returned to Tokyo, they stopped in Nagoya and lost two games to Aichi Prefectural High School (Aichi Dai-Ichi Chugaku), 7-3 and 9-4, but their greatest challenge loomed ahead—Waseda and Keio Universities.43

At 3 P.M. on Saturday, October 10, a beautiful warm fall afternoon with clear blue skies and the temperature just shy of 71 degrees, James Kondo took the mound against the Waseda nine.44 Although the university always fielded a top squad, the 1914 club was not one of Waseda’s strongest. The team contained two future members of the Japanese Hall of Fame, Tadao Ichioka and Tatsuo Saeki. Both were good players, but both were inducted for their later off-field accomplishments—Ichioka became the general manager of the 1934 All-Nippon team and the Yomiuri Giants, while Saeki became an umpire and organizer of high-school baseball.

Kondo held Waseda scoreless until the fourth inning, when Shirin Cho smacked a triple and Yoshio Asanuma, who later also became a general manager for the Yomiuri Giants, drove him in with a single. The collegians tacked on another three runs in the fifth as Cho singled in Kichibei Kato and then came home on a triple by Asanuma, who subsequently scored on a balk. In the eighth, Waseda scored two more runs on a bases-loaded infield hit by Kazuyoshi Yokohama to push their lead to 6-0. Meanwhile, Waseda hurler Tamizo Kawashima dominated the Asahi batters, striking out five and surrendering a lone hit to Yoshiaki Marumo. Asahi had a chance in the eighth when third baseman John Ikeda drove the ball to deep center field, over Cho’s head. Cho, however, sprinted back and to the fans’ delight made a diving catch to preserve the 6-0 shutout.

The next afternoon, the Asahi ended their tour against Keio University at the Mita grounds. For the second consecutive day, Kondo took the mound for Asahi. Keio hit him hard in the first inning, jumping out to a quick 3-0 lead. Most observers felt that this was the start of a one-sided rout, but Kondo regained control and shut down the Keio batters for the next seven innings. To nearly everybody’s surprise, Asahi scored one in the third and then surged ahead in the seventh on three-run homer by Ikeda. “Hugely confused,” Keio went to the bench in the eighth inning and brought in Kazuma Sugase and Akira Kusaka as pinch-hitters.45 The tactic worked as Keio rallied for four runs to win, 7-4.

With their fourth consecutive loss, the Asahi ended the baseball tour with a 2-7-2 record. They had lost all three contests against the collegians but had played evenly with some of Japan’s top high-school teams. Yet, as a cultural exchange the Asahis’ trip was a resounding success. The players learned about their parents’ homeland, attended receptions, and created ties with Japanese ballplayers. Frank Fukuda and the Asahi returned to Japan twice more—in 1918 and 1921—each time strengthening cultural and economic bridges between Japan and Seattle.

Other Japanese American teams followed the Nippon’s and Asahi’s lead. Between 1915 and 1940, 14 North American and six Hawaiian Nisei clubs visited Japan. Some went just to play baseball but many followed the philosophy of kekehashi and went to learn about their parents’ land and build bridges between the two cultures.

ROBERT K. FITTS is the author of numerous articles and seven books on Japanese baseball and Japanese baseball cards. Fitts is the founder of SABR’s Asian Baseball Committee and a recipient of the society’s 2013 Seymour Medal for Best Baseball Book of 2012; the 2019 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award; the 2012 Doug Pappas Award for best oral research presentation at the annual convention; and the 2006 and 2021 SABR Research Awards. He has twice been a finalist for the Casey Award and has received two silver medals at the Independent Publisher Book Awards. While living in Tokyo in 1993-94, Fitts began collecting Japanese baseball cards and now runs Robs Japanese Cards LLC. Information on Rob’s work is available at RobFitts.com.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Yoichi Nagata for providing me with Japanese-language newspaper accounts of the games and helping me with Japanese names; Tomohiko Oda for translating the chapter covering the Nippon’s tour in Yakyu-Nenpoh and the newspaper article welcoming the Nippon in Tokyo Asahi; Emi Kikuchi for translating the “Welcome Asahi Players!” article in Yokohama Boeki Shimpo, and Carla Grace for translating the chapter covering the Asahi’s tour in Yakyu-Nenpoh.

NOTES

1 “Johnstons Win Again,” Seattle Star, July 22, 1907: 2.

2 “Gossip About the Players,” Seattle Daily Times, May 24, 1908: 16.

3 “Unique Ball Game Played Here,” Seattle Daily Times, July 10, 1908: 16.

4 “Fast Mikado Baseball Team,” Seattle Star, July 9, 1910: 2.

5 “Jap Teams Get into the Game,” Tacoma Times, May 6, 1910: 2; Mikado baseball team with Northwest Japanese Baseball Tournament trophy, Seattle, 1911, Frank Fukuda Photograph and Ephemera Collection, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

6 Ryoichi Shibazaki, Seattle and the Japanese-United States Baseball Connection, 1905-1926 (Seattle: University of Washington Master’s Thesis, 1981), 87-88.

7 “Amateur Baseball,” Seattle Daily Times, July 6, 1912: 11; Shibazaki, 79.

8 “Tigers Beat Nippons,” Seattle Daily Times, March 23, 1914: 12; “Seattle Takes Game from Jap Team,” Seattle Star, March 30, 1914: 7; “Nippons Lose Well-Played Game,” Seattle Daily Times, March 30, 1914: 14.

9 “Nippons Defeat Fast Keio Team,” Seattle Daily Times, April 10, 1914: 21.

10 Cadreau is often called Bill Chouneau in baseball records.

11 “Redskin Is a Good Jap; Wins a Game,” Seattle Star, April 10, 1914: 13.

12 “Nippons Defeat Fast Keio Team.”

13 “Nippons Beat Asahis in Close Game,” Seattle Daily Times, July 13, 1914: 10.

14 “An Advance of 25 to 100 Per Cent on Grain and Flour Rates to Points in Orient,” Lewiston Fergus County Democrat, August 27, 1914: 9.

15 “Shipping and Mail Notices,” Japan Times, September 11, 1914: 6.

16 “Seattle Baseball Team Arrives,” Tokyo Asahi, September 11, 1914: 5.

17 “Seattle Baseball Team Arrives.”

18 Takuo Ito, ed., Yakyu-Nenpoh (Tokyo: Mimatsu Shouten, 1915), 25.

19 Ito, 26.

20 Ito, 28.

21 Ito, 28.

22 Ito, 29.

23 Ito, 32.

24 Ito, 30-32; “Seattlevs. Keio,” Tokyo Nichi Nichi, September 20, 1914: 7; “Keio Defeated,” Tokyo Asah, September 20, 1914: 5.

25 Ito, 32.

26 Ito, 34-35.

27 Ito, 37.

28 Ito, 39-41.

29 Ito, 41.

30 Ito, 42.

31 Ito, 42.

32 Ito, 44-46; “Seattle and Mita Tie,” ‘Tokyo Asahi, September 29, 1914: 5.

33 Robert K. Fitts, Issei Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 215.

34 “George Engle Back from Japan,” Seattle Daily Times, October 23, 1914: 21.

35 As Japanese sources rarely list players’ full names, the first names have been gleaned from various newspaper articles, census reports, and ships’ passenger lists. Japanese names are often misspelled in English documents so their actual names may differ from those listed in the chapter. The identification of Kondo as Sukehiko (born July 14, 1892, in Hawaii) is not definite but fits all available facts.

36 Shibazaki, 80.

37 Shibazaki, 80; see also Samuel O. Regalado, “Baseball’s A Bridge of Understanding and the Nikkei Experience,” in Mark Dyreson, J.A. Mangam, and Roberta J. Park, eds., Mapping an Empire of American Sport: Expansion, Assimilation, Adaptation and Resistance (New York: Routledge, 2013), 60-75.

38 “Watashitachi no Kokorogake—Bokuku no Tameni,” Mita Shimbun, September 19, 1918; translated and quoted in Shibazaki, 87.

39 “Welcome Asahi Players!” Yokohama Boeki Shimpo, September 23, 1914: 1.

40 “Welcome Asahi Players!”

41 The Kansai area is the second most populated region of Japan, consisting of Osaka, Kyoto, Nara, Wakayama, Hyogo, and Shiga Prefectures.

42 “Kansai ni okeru Shiatoru Asahi Yakyudan,” Yakyukai, Vol 4, No 12, inside cover, 8.

43 Nagoya Shimbun, October 7, 1914: 5; October 8, 1914: 5.

44 “Weather Report,” Japan Times, October 11, 1914: 4.

45 Ito, 57.