The 1908 Reach All-American Tour of Japan

This article was written by Rob Fitts

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

1908 Reach All-Americans with Mike Fisher (Rob Fitts Collection)

The “King of Baseball” was on the prowl for a new opportunity. Mike Fisher, known by everybody as Mique, was a bom promoter and bom self-promoter. He was a risk taker, tackling daunting projects with enthusiasm and usually succeeding. He was the quintessential late-nineteenth-century American man; through hard work and gumption this son of a poor Jewish immigrant transformed himself into a West Coast baseball magnate.

Bom in New York City in 1862, Fisher grew up in San Francisco. Renowned for his speed, he played baseball in the California League during the 1880s before an industrial accident in March 1889 damaged his left hand and sidelined his career. Fisher soon became a policeman in Sacramento, rising to the rank of detective. During his time away from the game, he put on weight and by 1903 was a repeat champion in the fat men’s races held at local fairs.

In February 1902, a new opportunity presented itself when the California League offered Fisher the Sacramento franchise. Fisher pounced on it. In December 1902, the league transformed into the Pacific Coast League, but within a year Fisher relocated his franchise to Tacoma, Washington. Hampered by poor attendance, despite winning the 1904 championship, Fisher sold his share in the team but stayed on as manager as the franchise moved to Fresno in 1906. But his stay in Fresno was short as he left the team after the 1906 season. Without a franchise, Fisher turned to promoting and, in the fall of 1907, took a squad of PCL all-stars to Hawaii.1

“So pleased is Mike Fisher with the reception that his team has met with here,” reported the Hawaiian Gazette, “that he is already planning for more worlds to conquer. He is now laying his lines for a trip to be made … next year, which will extend farther yet from home. … The plan, as outlined by Fisher, will include a start from San Francisco, with a team composed exclusively of players from the National and American leagues,” and a stop in Hawaii before continuing on to Japan, China, and the Philippines.2 It was the first time an American professional squad headed to the Far East.

By early December 1907, Fisher had teamed up with Honolulu athlete and sports promoter Jesse Woods to organize the trip.3 Woods sent a flurry of letters to Asian clubs to gauge their interest. In February, John Sebree, the president of the Manila Baseball League, responded “that Manila would meet any reasonable expense in order to see some good fast baseball by professional players.”4 In early March, Woods received a letter from the Keio University Baseball Club stating that they would help arrange games in Japan for the American team. The Hawaiian Gazette noted, “This was good news for Woods, who has been in doubt as how such a trip would be received by the Japanese. There has been so much war talk that Woods was afraid that Japanese might refuse to play baseball with us.”5 A letter in early April from T. Matsumura, the captain of the Yokohama Commercial School team, confirmed the enthusiasm for the tour in Japan: “When you visit our country, you would certainly receive a most hearty welcome from our baseball circles.”6 Isoo Abe, the manager of the Waseda University team, added, “We are preparing to give you a grand ovation. We are going to make you feel at home, and we will strive to make your visit to Japan to be one that will linger long in your memories.”7

In late June, Woods sailed for Asia to finalize the details for the tour. The touring team was now known as the Reach All-Americans. With the name change, it is likely that the A.J. Reach Company sponsored the team but despite extensive research, the nature of the sponsorship is unknown.8 Woods’s reports from the Far East were encouraging. “I have all the arrangements made. Forfeit money is up everywhere, and everything is on paper. The team will take in Japanese and Chinese ports and Manila.”9

While Woods was working out the itinerary, Fisher built his roster. As usual, he thought big. It would be “a galaxy of the best players in the country.”10 He began by engaging Jiggs Donahue, the Chicago White Sox’ slick-fielding first baseman, to manage and help recruit the team. “I do not know why Mike Fisher came to me to ask me to get up the team, for I did not know him,” Donahue told a reporter. “I will willingly undertake the work, however, for I believe it will prove to be a grand trip and a success.”11 Donahue quickly recruited fellow Chicagoans Frank Chance, Orval Overall, and Ed Walsh and began working on the leagues’ two biggest stars, Honus Wagner and Napoleon Lajoie. “Both Wagner and Lajoie are said to be enthusiastic over the plan,” reported the Inter Ocean of Chicago, “but cannot decide whether or not they will be able to arrange their affairs in such a way as to make the trip, which will last two or three months.”12 By June, Fisher had added New York Highlanders star Hal Chase, Chicago’s Doc White, and Bill Bums of the Senators. Although Wagner and Lajoie declined the invitation, Fisher’s team received a boost on August 23 when Ty Cobb announced that he would join the tour. The recently married star planned to take his bride on the trip as a honeymoon.

At the last minute, things began to unravel. First, Frank Chance and Ed Walsh decided not to go, then near the end of the major-league season Orval Overall, Doc White, and Jiggs Donahue dropped off the roster. In early September, Hal Chase deserted the Highlanders after a dispute with management and returned to his home in California. With Chase suspended from Organized Baseball, Fisher cut him from the team. The news only got worse.

On October 17, just two weeks before the team’s scheduled departure for the Far East, Ty Cobb announced that his wife was in poor health and that he might not make the trip. A week later Cobb was still undecided. After an appearance at the Georgia State Fair, he told reporters that he might winter in Georgia as “the hunting is a lot better around Royston than in Japan.” On October 27 Cobb officially announced that he would remain home with his ailing wife.13 The true reason for Cobb’s cancellation soon emerged. In mid-October, Cobb had demanded that Fisher pay travel expenses for his wife. Fisher refused. He would pay the players’ travel expenses as agreed but not for their guests. Not happy with the decision, Cobb pulled out of the tour.14

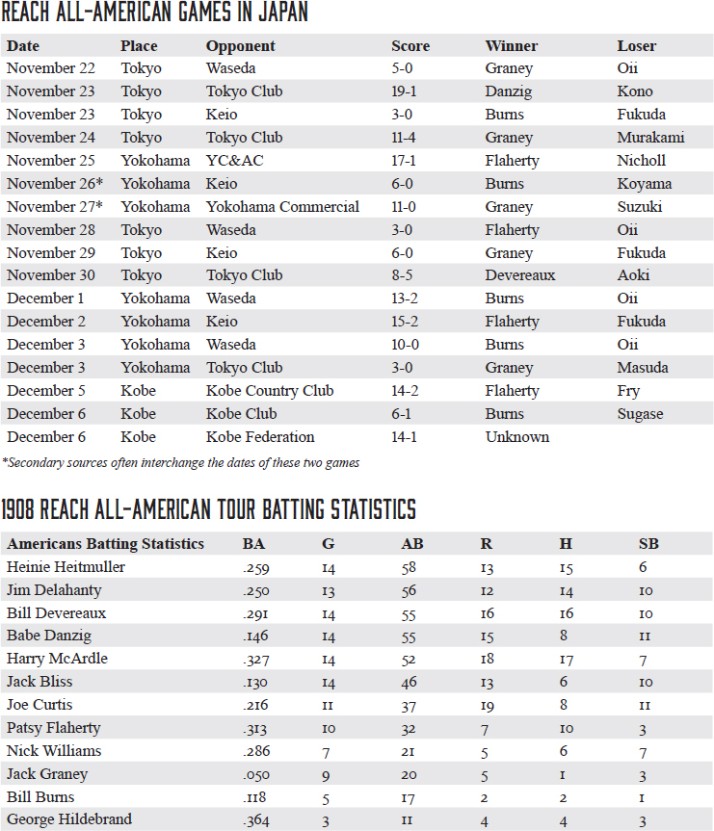

In place of the advertised “galaxy of the best players in the country,” the Reach All-Americans now consisted of four marginal big-leaguers (Jack Bliss, Bill Burns, Jim Delahanty, and Patsy Flaherty) and eight Pacific Coast League players (Joe Curtis, Babe Danzig, Bill Devereaux, Jack Graney, Heinie Heitmuller, George Hildebrand, Harry McArdle, and Nick Williams). On November 3 a large crowd gathered at the Pacific Mail Dock in San Francisco to wish the team luck as they boarded the S.S. China. After a brief stop in Honolulu, where the team played no games, the All-Americans continued to Japan.

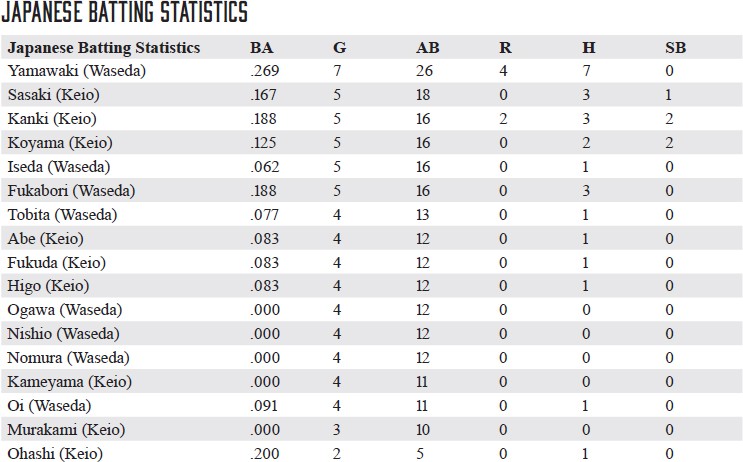

The All-Americans were the third US team to play in the Land of the Rising Sun that fall. In September, the University of Washington varsity became the first American college squad to visit the country. The team stayed for five weeks, playing 10 games against Japanese university clubs. A week after the Washington team left Japan, the American Great White Fleet, an armada of 16 battleships designed to display the country’s formidable power but painted white to symbolize peace, arrived in Yokohama. To emphasize shared values, the sailors played a series of nine baseball games against Keio and Waseda Universities. The visitors were no match for the college squads as Keio won all five of its games and Waseda won three of its four games.

The China arrived in Yokohama on Sunday morning, November 22, three days behind schedule. Although a launch packed with dignitaries met the ship before it docked, the elaborate welcoming ceremony was curtailed as the team needed to get to Tokyo for an afternoon game. An 11 A.M. train took the All- Americans to the capital, where they checked into the Imperial Hotel and changed into their gaudy uniforms.

Produced by the A.J. Reach Sporting Company, the uniforms consisted of scarlet blazers with blue bindings and a star on the left sleeve; white pants; white jerseys trimmed in blue with “Reach All Americans” in block letters across the front; and “a shield bearing the stars and stripes on the left arm.” Both the undershirt sleeves and “the stockings were startling productions resembling barbers poles with a series of parallel bands of red, white and blue.”15

The team traveled across town to open their tour against Waseda University, whose team had visited the United States in 1905, playing 26 games against collegiate, amateur, and California State League teams. Eight thousand spectators thronged the small ballpark, which contained no grandstands and only a handful of crude bleachers. Most fans sat on earthen embankments either on elevated platforms where they squatted on cushions or on seats terraced into the little hills.16 Reporter H.L. Baggerly, who accompanied the team on the tour, noticed, “In Japan, baseball is a man’s game exclusively, for as yet I have to see my first native woman in attendance. … We have found the spectators quite as enthusiastic as the Americans. Clever plays are liberally applauded, especially when made by the home club, and the [Japanese] start to root just as soon as they get men on base.17 To the Americans’ surprise, “the Japanese fans divided themselves into equal rooting sections, one side with the Stars and Stripes flying, yelling for the Yankees, and the other, Waseda enthusiasts, with the university pennants waving supreme.”18

As Count Shigenobu Okuma, the university’s founder and a former prime minister, prepared to throw out the ceremonial first pitch, the American pitcher Jack Graney “took his sporting cap and put it on the count’s head, replacing the latter’s silk hat. The count with a smile accepted this and holding the ball in his right hand cast it and it was caught by the catcher. The ceremony being duly ended amidst deafening cheers the game was opened.”19

Graney dazzled the Waseda batters.20 His “swerve and drop were produced in such variety and with such perfection that the batters might well be excused for fanning the air in fruitless efforts to strike the elusive ball.” As a result, “very little hitting was done by the home team. A few ‘flies’ rose into the air and fell into sure and steady hands, and only twice did a Waseda player get onto first base, whilst none of them ever got to second.”21 Although Hiroshi Oi pitched well, limiting the Americans to seven hits, the visitors’ timely hitting led to a comfortable 5-0 victory. The highlight was Heinie Heitmuller’s drive over the center-field fence, believed to be the longest hit made in Japan to that date.22 The friendly game was marred by an argument between an unidentified All-American player and the umpire. Although arguing with umpires had a long and colorful history in the United States, it was nearly unheard of in Japan and was a major breach of etiquette. “This incident, however, smoothed itself out.”23 Despite the loss, the visitors and the press praised the Waseda players for their “grit and ginger.”24

Keio’s ace Kazuma Sugase. (Rob Fitts Collection)

To make up the games missed by their tardy arrival, the All-Americans played a doubleheader on November 23 at the Mita grounds in Tokyo despite frigid temperatures and strong chilling winds. In the morning, they faced the Tokyo Club, an aggregation of graduated stars from Waseda and Keio universities. Several of the players, including pitcher Atsushi Kono, catcher Masaharu Yamawaki, and outfielder Kiyoshi Oshikawa, had played in the United States with the 1905 Waseda team. But the game turned into a mere warm-up as the visiting professionals pounded the former stars, 19-1. Aided by “a hurricane of wind which blew in the batters’ faces,” Babe Danzig “pitched so fast that the batters could do nothing with his shoots. … During this time the American players, through a combination of fourteen hits and eleven errors, ran up [the] score.”25

The main event was the afternoon match against Keio University, Japan’s top squad. During the recent games against Washington University and the Great White Fleet, Keio had swept all eight games. “In spite of the wind and dust,” reported the Japan Times, “the ground was crowded by spectators who numbered over 10,000.”26 “Seldom have I seen such interest in a baseball game in the States,” added Mike Fisher. The fans “had a sneaking idea that their crack team would whip us, and they wanted to see it done.”27

Fisher started his best pitcher, Bill Burns, who 11 years later would be one of the conspirators in the Black Sox Scandal, while Keio countered with Nenosuke Fukuda. The crowd witnessed a thrilling pitching duel. “There was no international courtesy about the game,” wrote B.W. Fleisher in Collier’s Weekly. “The Americans played ball for all they knew how. … Keio managed to hold down the All Americans to 1 to 0 until the eighth inning, neither side making a safe hit until the third.”28 The Americans tacked on two more runs to win 3-0. “They gave us a good fight as the score would indicate,” noted Fisher, “but we won and hope to win every game we play while we are away on this long trip.”29

After this tight game with Keio, the All-Americans were rarely challenged again during their stay in Japan. The next day, November 24, saw a rematch with the Tokyo Club. To make the game more competitive, the two teams swapped batteries. Graney and Nick Williams started for Tokyo while pitcher Denji Murakami and catcher (first name unknown) Yokote played for the Americans. But the swap did not go as planned. Murakami “walked three men in succession, and the Japanese [fans] thought it was intentional,” recalled Fisher. “It looked as if a riot would eventuate for a while. The rooters were calling us all sorts of names—fortunately, we did not understand [what] the crowd was yelling—so we pulled our pitcher out of the box.”30 With the pitchers back on their usual teams, the Americans won comfortably, 11-4.

After three days in Tokyo, the All-Americans moved to Yokohama. Founded in 1858 as a settlement for foreign traders, Yokohama soon grew into a major city with Western institutions including an English- language newspaper, brewery, racetrack, racquet club, and cricket club. By 1871, American residents had formed a baseball team and began playing at the Yokohama Cricket and Athletic Club. After visiting Japan, tour organizer Jesse Woods recalled, “My first stop was at Yokohama, Japan and I was taken to the Yokohama [Cricket] and Athletic grounds shortly after my arrival. It was a treat for me to find such a beautiful field almost in the center of the city. It is the finest I have ever seen, as far as turf is considered, and can only be compared to a billiard table. This field is surrounded by 1/2-mile bicycle and running track, inside are the cricket, baseball and tennis courts. … Conveniently located is the handsome clubhouse, with every facility that an athlete could desire. Refreshments are always served.”31 The club’s baseball team, consisting solely of foreigners, played a pivotal role in the development of Japanese baseball, when it lost three straight games to the all-Japanese First Higher School (known as Ichiko) in 1896. The victorious schoolboys became national heroes and spurred the spread of the game across Japan.

On November 25 the Yokohama Cricket and Athletic Club hosted the All-Americans. Nobutaka Mitsuhashi, the mayor of Yokohama, gave a short speech before throwing out the first ball. Although the club’s weekend warriors fought bravely, they “were outplayed from the start” by the visiting professionals and lost 17-1.32

The highlight of the series was the November 26 rematch against Keio University. A large enthusiastic crowd packed the stands at the cricket club. The All- Americans offered Keio a three-run handicap, which the collegians refused. “In consequence,” noted the Japan Times, it “was a spirited game.” Mango Koyama started for Keio and after setting down the Americans in the first, gave up three runs in the second. The All- Americans tacked on three more runs, finishing the game with six. Meanwhile, Bill Burns dominated the Keio hitters, allowing no hits into the eighth inning when Nenosuke Fukuda’s groundball somehow “flew over [the] pitcher and he got [on] first.” Bums walked the next batter before pinch-runner Eizo Kanki was thrown out trying to steal third to end the inning. That would be all for Keio as the Americans cruised to a 6-0 victory in just 1 hour and 15 minutes.33

The next day the All-Americans defeated the city’s other club, the Yokohama Commercial School, 11-0. In Tokyo, on November 28, Patsy Flaherty, starting his first game on the tour, bettered Burns’s performance by throwing a perfect game against Waseda University as the Americans won, 3-0. Strangely, the game was not covered in the English-language newspapers in Japan.

The All-Americans spent the next week in the Tokyo area, splitting their time between the capital and Yokohama, as they continued the series against Keio, Waseda, and the Tokyo Club with a pair of games against each. The Americans won each game comfortably, finishing off Keio 6-0 and 15-2, Waseda 13-2 and 10-0, and Tokyo 8-5 and 3-0.

As the team traveled around Tokyo, the players were stuck by the popularity of America’s national pastime. Bill Devereaux noted, “The first game we played was at Tokyo. It was on a Sunday. To reach the grounds from our hotel we had to drive fully two miles, and on our way we passed several parks and, believe me, there were baseball games between small boys and big in every one of them.”34 “Every college, every high school, every middle school in Japan has its baseball team, and judging by the number of apparently infantile youngsters who sport baseball uniforms in the parks, the primary and kindergarten schools are similarly equipped,” explained reporter Joseph Ohl. Even “Japanese girls take great interest in baseball. They are not much in evidence at the college contests, for these are held within the college enclosers: but there are always many of them watching the games in the parks. They flock by themselves, understand the game and show understanding by discriminate applause. They go to see the game, not to flirt, and they devote their whole attention to what is going on in the field; which may be hard to believe but is nevertheless true.”35

On December 4, the All-Americans left Tokyo by train for Kobe. According to the Morning Union, “Fisher secured a special car for his men, who traveled in all the luxury possible in this country. Everything went along smoothly until lunch. … A Japanese dining car, like the other cars here, is about the size of a chicken coop and the provisions are in proportion to the size of the cars. The players gave the dining car an awful storming at lunch, and after dinner there wasn’t enough food left to feed a sick canary. It was the conductor’s first experience with a bunch of hungry ballplayers, who can eat as no other set of men. As an illustration, Bill Devereaux devoured three orders of ham and eggs and one steak.”36

Their first game in the new city was on December 5 against the Kobe Country Club, a team consisting of Americans living in the city. Like their rivals in Yokohama, the recreational ballplayers were no match for the visiting professionals. “The Americans simply toyed with the Kobe boys, winning by the one-sided score of 14 to 2. Flaherty, who pitched, didn’t half extend himself and besides holding Kobe down to a few hits slammed out a couple of home runs.”37

The All-Americans closed out their official games with a doubleheader on December 6. In the opening, the professionals faced the Kobe Club, an aggregation of the local squad and the top players from Keio University. On the mound for the Japanese was the tall, bespectacled 18-year-old Kazuma Sugase, the son of a German father and Japanese mother. He would become the best pitcher of his generation and was singled out by John McGraw as “one of the greatest all-around athletes in Japan,” but he could not hold the Americans, who won 6-1. In the second game, the All- Americans embarrassed the local Kobe Federation, 14-1.38 The Kobe games were so popular that local fans persuaded the All-Americans to play two informal games the next day. In the first match, the city’s top high-school players, reinforced by some members of the Kobe Club, had a chance to play against the professionals. Not surprisingly, the All-Americans won easily, 10-0. The second match was a pickup game with combined-roster teams, played just for fun. Neither of these last two games was included in the official tour results.39

During their two-week stay in Japan, the All-Americans won all of their 17 games by a combined score of 164 to 19. One reporter noted that “if the boys had tried awfully hard, they could have blanked them in nearly every contest.”40 “We are insects compared with the giants,” a Keio player supposedly concluded.41 Observers noted, “the weak point of the Japanese team is their batting. … [but] considering that they are novices at the game, they are simply marvelous at all the other points. They are quick, active, and heady.”42 “They put up a mighty nice fielding game,” noted Bill Devereaux. “The infield work of the Keio club was as snappy and fast as any I’ve seen this season. … They don’t bat the ball as hard as we do, but they are going to improve.”43 “They watch the playing of our men with the keenest attention,” explained Fisher. “They are anxious to pick up the fine points and become expert at playing our national game.”44

H.L. Baggerly noted, “While the attendance of the games of the All-Americans has exceeded expectations, the receipts are only fair. Ten, 20 and 30 cents are the maximum prices a manager can charge right now and get the money. There are hard times in Japan as well as America. … Wages are very low. … Hence if a [Japanese] gives up 30 cents at the box office to see a baseball game he is parting with a large chunk of his salary.”45 The exchange rate also hurt Fisher’s bottom line. While 30 cents was dear to a Japanese worker, it barely covered Fisher’s expenses. “Mike Fisher … almost fainted on the diamond when he saw the huge crowd that came out for the first game,” wrote columnist Bob Ray in 1934. “Mike’s team’s share of the receipts was so big he had to hire a truck to haul the huge pile of coin down to the bank. ‘I had visions of retiring and becoming one of the filthy rich,’ says Fisher ‘But when we got to the bank and exchanged it for American money, that big truck-load of coin amounted to only $18.75.’”46

On December 7 the All-Americans sailed for Shanghai, where they played a doubleheader against the local club, before moving on to Hong Kong and Canton.47 In the British colony, they played a mixed doubleheader—a baseball game and a cricket match. Not surprisingly, the Americans won at baseball, but cricket was another matter. “The Hongkongers kept slugging away and we hadn’t got them out by teatime,” recalled Devereaux. “They had scored, if I remember rightly, 678 runs for six men out. Oh, but it was a painful experience alright!”48 The team arrived in Manila on Christmas. Although baseball had only been introduced to the Philippines 10 years earlier, US troops stationed on the islands gave the All-Americans their first stiff competition during the tour. The professionals played six games against military teams and four against squads of expatriates aided by Filipino schoolboys enrolled in missionary schools. Army teams beat the professionals twice and lost another by a run in 11 innings. After a brief stop in Japan, the All- Americans finished their tour in Hawaii, where they won three games comfortably against the All-Hawaii team before losing the last game, which featured Bill Bums on the mound and Jack Bliss behind the plate for the All-Hawaiians.

As the All-Americans returned to San Francisco on February 15, Fisher was pleased with the team’s accomplishments. “Our trip through Japan should go down in history, as it was one of the greatest baseball invasions ever made. We won [over] the people every place we went, and we sent all of Japan baseball mad.”49 H.L. Baggerley summed up the tour perfectly: “I can say without fear of contradiction that the trip has been an unqualified success and promoters Fisher and Woods are entitled to all the glory. From a financial point of view, it has been successful. Money has been made—not a mint of money, but enough to remunerate the enterprising promoters for their labor and loss of time. … The All-Americans have done some noble missionary work. They have made scores of converts to our national game. It would be a great thing if a team could tour the Orient annually. Interest in baseball would intensify with every visit. Japan has caught the spirit and will welcome with open arms any and all ambassadors of our national game.”50

ROBERT K. FITTS is the author of numerous articles and seven books on Japanese baseball and Japanese baseball cards. Fitts is the founder of SABR’s Asian Baseball Committee and a recipient of the society’s 2013 Seymour Medal for Best Baseball Book of 2012; the 2019 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award; the 2012 Doug Pappas Award for best oral research presentation at the annual convention; and the 2006 and 2021 SABR Research Awards. He has twice been a finalist for the Casey Award and has received two silver medals at the Independent Publisher Book Awards. While living in Tokyo in 1993-94, Fitts began collecting Japanese baseball cards and now runs Robs Japanese Cards LLC. Information on Rob’s work is available at RobFitts.com.

NOTES

1 Thom Karmik, “Mique Fisher and the POL,” Baseball History Daily, May 6, 2013. https://baseballhistorydaily.com/20i3/o5/o6/mike-fisher-and-the-pacific-coast-league/.

2 “Fisher Plans Trip to Orient,” Hawaiian Gazette, November 29, 1907: 5.

3 “Fisher’s Stars Love That Dear Honolulu,” Grass Valley (California) Morning Union, December 10, 1907: 7.

4 “Manila See GoodBall,” Honolulu Advertiser, February 18, 1908: 3.

5 “Baseball Tour to Orient,” Honolulu Hawaiian Gazette, March 3, 1908: 5.

6 Frank B. Hutchinson Jr., “Local Players to Invade the Orient,” Chicago Inter Ocean, May 10, 1908: 18.

7 “Ball Team for Japan. Mike Fisher Will Take a Strong Nine to the Land of the Mikado.” Brooklyn Daily , June 4, 1908: 8.

8 Keith Robbins, “The 1908 Reach All American Tour,” unpublished manuscript in author’s collection.

9 “Jess Woods Has Trip of Star Team to Orient All Fixed,” Honolulu Evening Bulletin, September 21, 1908: 7.

10 “Woods Will Take Team,” Honolulu Advertiser, March 24, 1908: 3.

11 “Jiggs Donahue Going to Japan,” Pittsburgh Press, March 19, 1908: 8.

12 Hutchinson.

13 “Cobb’s Trip to Japan Doubtful,” Detroit Times, October 17, 1908: 2; “Cobb May Cut Out Jap Trip and Spend Winter in Georgia,” Atlanta Georgian and News, October 23, 1908: 36; “Cobb Abandons Trip to Japan,” Topeka State Journal, October 27, 1908: 2.

14 “Cobb Will Be Left at Home,” Butte Daily , October 31, 1908: 6.

15 “Reach-Alls Far Too Good for Orient,” Hawaiian, December 7, 1908: 6.

16 H.L. Baggerly, “Japs Eager to Become Expert in Baseball,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, December 20, 1908: 28.

17 Baggerly, “Japs Eager to Become Expert in Baseball.”

18 “American Nine Defeats Waseda,” Oakland Tribune, November 23, 1908: 11.

19 “The Reach All Team,” Japan Times, November 25, 1908: 6.

20 Despite the attention given to the tour, accurate box scores do not survive for all games. Some published box scores are incomplete and contain errors. There are also discrepancies between articles published in Japanese and English, making it difficult in some cases to verify the starting pitchers. For example, some articles state that Bill Burns started this first game. Furthermore, the first names of the Japanese players were rarely published so these are sometimes lost to time.

21 Joseph Ohl, “Japan Coming Along with Baseball Game,” Duluth News Tribune, November 8, 1908: 2; “Reach-Alls Far Too Good for Orient.”

22 “Japs Give Champs a Royal Time,” Grass Valley Morning Union, December 16, 1908: 7.

23 “Reach All Stars Far Too Good for Orient.”

24 “American Nine Defeats Waseda.”

25 “Japs Give Champs a Royal Time.”

26 “The Reach All Team.”

27 “Mique Fisher Is Heard From,” Pacific Commercial Advertiser, December 5, 1908: 3.

28 B.W. Fleisher, “Baseball in Japan,” Collier’s Weekly 42, no. 15: 29.

29 “Mique Fisher Is Heard From.”

30 “Michel Fisher’s Impressions,” Honolulu Evening Bulletin, February 10, 1909: 7.

31 Jesse Woods, “All the East Has Baseball Fever,” Grass Valley Morning Union, October 8, 1908: 7.

32 “Baseball,” Japan Weekly Mail, November 28, 1908: 654.

33 “Reach and Keio Baseball,” Japan Times , November 27, 1908: 2.

34 Bill Devereaux, “Baseball Nippon’s National Game,” Honolulu Evening Bulletin, February 2, 1909: 6.

35 Ohl.

36 “All Americans Are Champion Eaters,” Grass Valley Morning Union, December 29, 1908: 7.

37 All Americans Are Champion Eaters.”

38 Conflicting sources exist for the final games in Kobe. Yoshikazu Matsubayashi lists a doubleheader on December 6 while Shinsuke Tanaka notes a single game on the 6th and a doubleheader on December 7. Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs. U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2001); Shinsuke Tanaka, Kobe no Yakyushi: Reimeiki (Kobe: Rokko Shuppan, 1980), 644-656.

39 Tanaka, 654-656.

40 “Jack Graney Pitches Great Ball in Japan,” Oregon Daily Journal (Portland), December 29, 1908: 9.

41 Fleisher.

42 Fleisher.

43 Devereaux.

44 “Mique Fisher Is Heard From.”

45 Baggerly, “Japs Eager to Become Expert in Baseball.”

46 Bob Ray, “The Sports X-Ray,” Los Angeles Times, November 9, 1934: Part II, 14.

47 “Baseball Team in China,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening News, January 29, 1909: 8.

48 “Mike Fisher’s Players Arrive,” Hawaiian Star, January 30, 1909: 3.

49 Mike Fisher, “Baseball Tour of Americans a Success,” San Francisco Call, February 16, 1909: 8.

50 H.L. Baggerly, “Baggerly Writes of Travels of Baseball Champions,” Honolulu Evening Bulletin, January 30, 1909: 1, 3.