Restart of Legend: The Waseda-Chicago Rivalry 1910-2008

This article was written by Christopher Frey

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

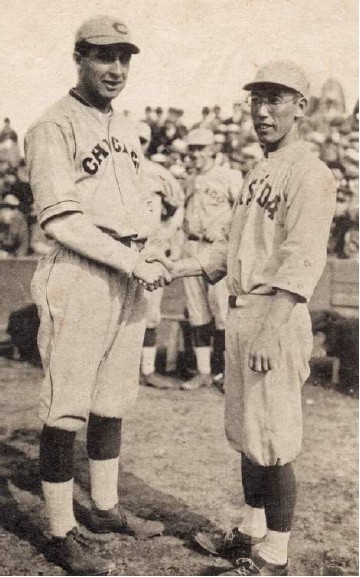

1930 University of Chicago team in Japan. (Rob Fitts Collection)

On the fourth day of spring in the 20th year of the Imperial Heisei era, just as the cherry blossoms were starting to bloom, another chapter in one of the most significant stories in US-Japan sports history was about to be written. It was Saturday, March 22, 2008, and while the Boston Red Sox held off the Hanshin Tigers and the Oakland Athletics rallied to beat the Yomiuri Giants in an exhibition double bill at Tokyo Dome, what really mattered that day was the long-awaited return of another American baseball team: the University of Chicago Maroons.1

The Chicago squad was coming for its sixth Japan tour, once again at the invitation of Waseda University, as part of that prestigious Tokyo-based institution’s 125th-anniversary celebrations.2 Given that the first time the Maroons came was in 1910 while the last had been in 1930—not to mention Waseda’s five return tours between 1911 and 1936—Chicago’s arrival was touted as renewing a nearly 100-year-old rivalry, with promotional posters and merchandise declaring it to be the “Restart of Legend.”3

The matchups between Waseda and Chicago in the late-Meiji, Taisho, and early-Showa eras were truly epic battles fought on both sides of the Pacific, yet they sprang from the labors of an idealistic Japanese professor with support of two Maroons turned missionaries, so these baseball exchanges were always imbued with goodwill. As the 10 series were contested over the course of three decades, American dominance slowly gave way to spirited Japanese play inspired by the unlikely pairing of a manager who derided putting too much importance on results and his team’s former captain turned coach who became hellbent on winning. And although the two teams were torn apart by war, the baseball ties between Chicago and Waseda would fully heal when at long last their legendary rivalry was restarted in 2008.

The bond between Waseda and Chicago began forming in 1904, shortly after Fred Merrifield—former standout third baseman and Maroons captain—was sent to Tokyo as a missionary by the American Baptist Union.4 By the time Merrifield arrived, Waseda had just won Japan’s college baseball crown quite impressively, doing so only a few years after Professor Isoo Abe—one-time pastor and graduate of Doshisha and Hartford Theological Seminary—established their first full-fledged team in 1901.5 Abe had inspired his men to the title by promising that if they won he would arrange a trip across the Pacific to play against other university nines. Upon learning that a former Chicago ballplayer was teaching Sunday school nearby, Abe begged the American to become their part-time coach.6 Merrifield was happy to help and spent several days a week with the club. Although he wasn’t able to accompany Waseda to the United States due to his missionary obligations, he suggested they take a token of his baseball pedigree with them by adopting the same type and color of lettering he had worn while playing for his alma mater. So Abe’s team embarked on the first-ever foreign trip by a Japanese sports team donning jerseys with “Waseda” emblazoned in the same shade of maroon worn by Chicago.7 Merrifield then said in a letter published by the Chicago Tribune: “Give the Japanese player a little more training in the fine points of the game and I prophesy he will hit your curves, field and slide with the zest, and make his share of the fun. And then, after bowing politely to the umpire, he will go home and teach his younger brother to do still better at the great game of baseball.”8

After Waseda returned with a decent record of 7-19, Merrifield resumed coaching the team. By early 1907 he and Abe were trying to arrange a tour all the way to Chicago; but before a plan could be set, an illness forced his resignation from the Baptist Union. Yet it still seemed providence was at play, for another former Maroon standout was soon on his way.

Alfred Place, who hit a club-best .357 playing alongside Merrifield in 1900, was being sent over by the Foreign Christian Ministry.9 It was reported that “[h]e will work among the students of the Imperial and Waseda universities … and while he is teaching them athletics, he will also endeavor to win them over to Christianity.”10 After arriving in Tokyo in January of 1908, Place helped Waseda secure wins over the University of Washington later that year and the University of Wisconsin during its Japan tour in 1909.11 Now with some success against American teams on both sides of the Pacific, on April 18,1910, Abe wrote to University of Chicago Director of Athletics Alonzo Amos Stagg, issuing a formal invitation:

It is a great pleasure for me to ask you if it is possible for the University of Chicago baseball team to come over to Japan. … If you come here next fall, all the baseball fans will surely welcome you with open arms. … You know Fred Merrifield and Alfred Place have done a great deal in coaching our teams, and we believe we can give you tolerably good games if you would come here.12

It was agreed that Chicago would tour Japan that October and play five games against both Waseda and Keio University.13 Although Stagg regretted to inform Abe he couldn’t “visit Japan with the boys” due to football-coaching duties, he would do everything he could to ensure that his team was ready.14 After receiving Place’s scouting reports as well as insights from Merrifield, who was now living in Michigan, captain J.J. Pegues later recalled, “[W]e determined to go prepared to play our best game,” while noting that they spent the summer practicing and playing against local semipro teams.15 Pegues added, “As a result, we were really in better shape for a hard series in the fall than during the regular spring college season. … The teams of Waseda and Keio also spent the summer months in practice; so that all three teams were in the pink of condition.”16

The Chicago team even took lessons on Japanese language and culture, then were honored with letters of introduction to the Imperial Japanese government from President William Howard Taft and Secretary of State Philander C. Knox.17 Shortstop Robert Baird recounted in 1976 that their trip was deemed “an opportunity for each member of the team to consider himself as an American ambassador of goodwill to improve relations between the two countries.” Baird added, “Even today, sixty-six years later, I am sure that every one of us accepted this responsibility to a high degree.”18 All of this preparation served them well, for upon arriving at Yokohama aboard the Kamakura Maru on September 26, 1910, they were surrounded by reporters.19 As Pegues later detailed in an article for The Independent:

Thruout [sic] our stay we were considered not only as guests of Waseda University, but also as guests of the Japanese nation, and while objects of constant curiosity, we were at the same time subject to every form of Japanese politeness. Also I may say that while the Japanese stared at us constantly and questioned us continually, we returned both stares and questions with interest, as they seemed far stranger to us than we can have seemed to them. … When we were hauled thru the streets of Yokohama in “rickshaws,” on our way to the train for Tokio [sic], we insisted on leaving the tops of our man-drawn carriages down in spite of the steady rain; so that we might have an unobstructed view of the strange sights … and it was only thru stern necessity that we forewent sightseeing during our first few days in Tokio [sic], and devoted our time to practising [sic] for the games now close at hand.20

Pegues noted how they were “requested to practice in secret as far as possible, and without previous announcement, as it was feared students would desert their class-room work to watch us in action.” Yet large crowds still came to see the Maroons train, leading him to declare, “Only a ‘world’s series’ could excite such interest at home, and we looked forward with much curiosity to the first game.”21 In the meantime, the players stayed at the Imperial Hotel and were guests of honor at a banquet held at a Western-style restaurant fit for dignitaries, with Abe presiding while the American team’s chaperone, Professor Gilbert Bliss, said the University of Chicago hoped to return the favor the following year.22

Stagg had appointed his ace, Harlan Orville “Pat” Page, as the team’s player-manager, who, in addition to his baseball duties, served as a “Special Correspondent” for the Chicago Tribune. In Page’s report about that evening, he described how, “Following the twenty courses of both American and Japanese variety the two teams sang their alma mater, and the old Chicago yell drowned out the Waseda battle cry, although the new dress suits of the Maroons interfered with the vocal efforts.”23 The US ambassador to Japan, Thomas O’Brien, also hosted Chicago along with players from both the Japanese universities, as well as “a number of the Japanese nobility,” including Waseda’s founder and former Prime Minister Shigenobu Okuma.24 “After a musical concert the guests adjourned to the garden, where American dainties were served,” Page recalled, and then added that “Mr. O’Brien promised to be with the Maroons at the games.”25

When the day finally arrived for the opener, “The fences were draped with red and white bunting and the entrance festooned with American and Japanese flags,” Pegues recalled and then noted, “Practically all of the spectators had entered the field when we arrived, an hour and a half before the game was to commence, and as we passed in we were greeted with a great outburst of handclapping.”26 Despite lopsided support for Waseda, Pegues acknowledged how “[e]veryone rose to salute us and then settled down once more and waited for the game to start.”27 Before getting underway, Waseda’s cheer captain Nobuyoshi “Shinkei” Yoshioka—infamously known as the “Heckling Tiger Beard Shogun”—led a parade of the team’s most hard-core supporters down behind the third-base line.28 Yoshioka had been recruited a few years earlier to lead the cheering squad after Abe observed that students in America would chant their “college yell to take away the enemy’s spirit.”29

Afforded the courtesy of whether or not to bat first, Chicago elected to start off in the field, with Page on the mound and Fred Steinbrecher behind the plate, William Sunderland at first, Omo Roberts at second, John Boyle at third, and Baird at shortstop, with an outfield consisting of Mansfield Cleary in left, Frank Collings in center, and Pegues in right, while on the bench were pitcher Glen Roberts, catcher Frank Paul, and outfielder Herman Ehrhom.30 So aligned, Page threw out the first pitch at 10 minutes past three o’clock on October 4.31

The leadoff hitter for Waseda was second baseman Keito Hara, who to the delight of Shogun Yoshioka and the Japanese fans “drove a clean hit to the outfield,” and as Pegues recalled, “to our amazement, as we had expected absolute quiet, the whole crowd rose as one man and yelled till they were hoarse.”32 Yet instead of becoming rattled by the chorus of cheers, Pegues said, “Once the noise commenced we felt natural. The odd surroundings faded out of our minds and we were playing baseball, not some queer Japanese game.”33 Chujun Tobita flied out to Collings in center and third baseman Takeshi Iseda’s fly to Pegues advanced Hara to second, but Page then induced a grounder from Hitoshi Oi to end the threat.34 In the bottom of the first, with Oi on the mound, Collings grounded out but Pegues tripled and came home on a passed ball. Then Boyle walked and scored when Steinbrecker hit one over Jukichi Ogawa in center.35 Chicago tallied three more in the second, one each in the fourth and sixth, and two more in the eighth.36 The Japanese scored once in the sixth as catcher Sutekichi Matsuda hit a triple and scored on a fly out to center, and Ogawa scored an unearned run in the seventh, but as Iseda tried to score in the ninth, he was thrown out at home to end the game as a 9-2 Chicago victory.37 Yoshioka was disappointed that the team hadn’t done better and Tobita felt largely responsible after going 0-for-4, but they must have felt even worse upon seeing Keio lose to Chicago by only two runs.38

In the second game against Waseda, Tobita tried to make amends by going 3-for-4 with a steal and showed his determination by knocking Glen Roberts to the ground when they collided at first base, but his team’s only other hits were a triple by left fielder Goro Mikami and a single by pitcher Takayuki Omura, as Roberts fanned 11 in the 5-0 shutout.39 Chicago then crushed Waseda 15-4 in their third game and went on to rout the school’s alumni, 11-2, while it twice took them 10 innings to beat Keio in their next two matchups.40

Waseda and Chicago then traveled to Osaka, where, as Page wrote, “The teams were greeted at the Imperial station with many flowers and escorted through the city by a Japanese lantern parade.”41 With everything organized and promoted by the Mainichi Shimbun, there were more than 12,000 in attendance at the first game, and Page heard “that a number camped on the ball grounds all night so as to see the Maroons in action.”42 Osaka’s mayor threw out the first pitch and it seemed the tides had turned in favor of Waseda, which took an early lead against Roberts, but Chicago’s hitting proved too much: The team rallied and cruised to an 8-4 win.43 “Before the largest crowd of the international series,” Chicago then crushed Waseda, 20-0, as Page declared, “Never before was such a swatfest witnessed in Japan.”44 In the finale, Waseda took an early lead but ultimately lost yet again by another lopsided score, 12-2.45

As the players returned from Japan unbeaten, several hundred students gathered to “welcome home the University of Chicago baseball team, from its triumphal invasion of the Orient.”46 A few days later the players were “formally welcomed at a spirited and joyous baseball mass meeting,” and a theater troupe put on an “American-Japanese Night performance.”47 The team was praised by Stagg, who along with Japanese Consul Keiichi Yamasaki then jointly proclaimed, “[I]f Japan and America ever were to have a war, it would be in the form of a baseball contest.”48

In Tokyo, Abe tried to remain optimistic by telling the press that Chicago was a top team on par with Harvard and Yale, but critics were still harsh about the team’s embarrassing losses.49 Tobita claimed responsibility and quit.50 Losing so badly devastated Tobita, who described his initial encounter with the sport while in elementary school at the age of 10, saying, “From the first day I saw the leather ball, it was as if my heart had completely taken up residence inside it.” Yet it wasn’t his first time being crushed by defeat. When Tobita was 16 and playing competitively for his school in Mito, it became clear how much the sport meant to him. After his previously undefeated team lost a game to Ibaraki prefectural rivals Shimotsuma, he “cried tears of regret” as the opposing “troops” were “wrapped in honor.” At that time, Tobita would later recall, “What I vowed secretly in my heart was the great desire to avenge Shimotsuma.” Starting that following day, Tobita set to work with his teammates, who were desperate to “erase the only stain they had left,” but a rematch was never secured and so they had to settle for vicarious vengeance by defeating the Ikubunkan team from Tokyo after hearing that they had beaten Shimotsuma. Tobita suffered another humiliation when he was held hitless in a 15-0 drubbing by Keio University’s feeder school, after which he admitted, “We were ashamed to go home in broad daylight, so we waited for dusk and snuck home through the back gate.” This time, he and his teammates would eventually exact revenge directly, but Tobita’s animosity apparently stayed with him as he decided to enroll at Keio’s archrival in 1907. Yet when Tobita joined Waseda’s baseball team that spring, the notoriously explosive “Sokei-sen” series of baseball “battles” with Keio were still on hiatus due to concerns from administrators that emotions on and off the field had been getting way out of hand. Now, just three years later, feeling horrible that he had let Chicago stain the reputation of both his team and that of Abe, he essentially committed baseball harakiri by walking away from the game.51

Abe’s reputation took a serious hit, too, and his tenure as manager was even in doubt when he reportedly resigned ahead of Waseda’s upcoming 1911 tour of America. Yet it was later clarified that Abe “was unable to come, occupied as he is with his faculty work and the worries involved as president of the baseball association.”52 Whatever the case, Abe then made a managerial change that, although only temporary, surely had an impact on his players both on and off the field.

Although the ballclub was chaperoned by Professor Takizo Takasugi, the man whom Abe asked to take charge of Waseda’s team was their former foe and recent graduate, Pat Page.53 This wasn’t simply aimed at trying to improve the skills of his squad, for these exchanges weren’t just about wins and losses to Abe, as he first made clear on their 1905 tour when he told an audience at Stanford:

We are not here to win games, but to learn to play baseball as it is played in America. And it is not in baseball only that this trip should be a help to our men. It will broaden their views and help them to a better understanding of the world, and I expect they will gain from it far more than they put into it.54

After returning from that trip, he and his captain, Shin Hashido, shared the latest techniques they learned in America, which Abe then combined with his own spiritual and moral views to create a new form of Japanese baseball philosophy.55 In Abe’s lecture, entitled “Three Primary Virtues of Baseball,” he spoke of “wisdom, humanity, and courage,” while he “communicated to the team the importance of cultivating and strengthening the spirit.” He insisted that his team adhere to two key principles: “The first is to fight with the same passion throughout the entire match. … The second is to avoid placing all importance on winning or losing.”56 Abe shared similar sentiments with Page before his team’s departure for America, writing that “international friendship was more important than any other consideration in making the trip.”57 Page clearly valued the friendship too, for he gave up a chance to pitch an exhibition game against the Cubs so he could be in San Francisco when Waseda arrived on April 13, 1911, and even though the team went on to lose all three of its matches against Chicago and ended the tour with a record of 17-35-1, Page was encouraged by their performance.58 Waseda may have fared even better if Page hadn’t prematurely relinquished his management duties to get married in mid-June, at which point the entire squad saw him off as guests at his wedding.59

After his honeymoon, Page went to work at his alma mater as a coach under Stagg, so four years later when the Maroons returned to Japan in 1915, he was once again managing Chicago against the Japanese.60

Waseda now had Atsushi Kono as its part-time coach, the hurler mentored by Merrifield who earned the nickname “Iron Man” while pitching 24 out of 26 games during its 1905 tour. Fans hoped that his coaching would help his pitchers tame Chicago’s bats. Although Waseda’s pitchers fared better than in 1910, Chicago won the opener 5-3 in front of a crowd of 20,000. Then the Maroons swept the Tokyo series by winning the next three games 2-0, 1-0, and 5-0, with the latter a masterpiece by Page, who abandoned his role as manager to take the mound and faced only one over the minimum while striking out nine.61

As with the 1910 tour, three additional games were then played in Osaka. The Maroons shut out Waseda 3-0 in the opener behind the pitching of Paul “Shorty” Des Jardien, a 6-foot-4 ace who reportedly agreed to join the Cubs upon graduating but instead stayed with the Maroons to go to Japan. But in the second game, Rowland George spotted Waseda a three-run lead. Fearing Chicago’s unbeaten streak in Japan was in jeopardy, Page lifted George and took over on the mound, pitching in relief and holding Waseda scoreless the rest of the way as the Americans rallied and won 5-3. The Maroons then completed their sweep with a 9-1 victory in the finale, which, combined with three wins over Keio in Tokyo, gave Page and the university another perfect Japan tour record.62

Backup first baseman Dave Wiedemann saw little on-field action during that tour, yet in 1973 at the age of 78 he recounted the trip fondly: “We were royally entertained because at the time Japan was one of the Western Allies and Prime Minister Okuma also was honorary president of Waseda.”63 Okuma had taken time to entertain the Maroons in the garden of his private villa, where he told them, “Chicago’s visit in 1910 did much for younger Japan,” and declared that baseball “has practically become the National sport of Japan.”64 Okuma added, “Exchange visits by athletic organizations form a real means of promoting better understanding and peaceful sentiment,” before concluding his remarks by expressing his “hope that the relation of the University of Chicago and Waseda University would always be cordial.”65 Relations at that time were clearly cordial, for no one objected to Page playing even though he was technically ineligible, with everyone instead simply marveling at his pitching prowess. This served as another example of Abe’s insistence that his players not place too much importance on winning or losing.

In 1916 Waseda went on a return tour to the United States and once again lost all three of its games in Chicago, this time not even coming close, falling 7-1, 9-2, and 8-4.66 They would have to wait another four years for a chance to beat their American rivals, but for the next series in Japan, Waseda was to have its first full-time coach. Abe previously discussed the idea of dedicating someone to the job, but the problem was securing funds for a salary. After he consulted with the alumni club, it was decided membership fees would be charged to raise money for that purpose.67 Hearing of the plan, Tobita was instantly intrigued, for over the past 10 years every time he watched baseball he was tormented by the losses suffered to Chicago in 1910. He nearly gave up his ideas of vengeance as he wondered if his children might one day repair his legacy, yet knew that such an idea was ridiculous to expect of his own boys. But now Tobita realized, “Maybe I could get revenge on Chicago with my own hands.”68

Despite his wife’s apprehensions, given that the position paid two-thirds less than what he earned as a reporter for the Yomiuri Shimbun, Tobita thought, “I couldn’t afford to throw away a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to avenge Chicago,” so he took thejob.69 Coach Tobita then became a man possessed—described as looking like a demon on the diamond—as he prepared his team for its next battle with Chicago.70 Practices were so arduous that they became known as “Death Training,” yet Tobita simultaneously embraced some aspects of Abe’s baseball philosophy.71 “The purpose of training is not health but the forging of the soul, and a strong soul is only born from strong practice,” Tobita explained, while stressing, “In many cases it must be a baseball of pain and a baseball practice of savage treatment.”72 Although many were unsure of his methods, Tobita proudly said that his players “truly enjoyed baseball and practiced hard with a cheerful spirit.”73 Most important to Tobita was that his players were now also eager for their chance at vengeance against Chicago.74

When the Maroons returned to Japan in 1920 for their third tour, they too had a new coach. Page had moved on to Butler University and handed the reins over to Fred Merrifield, who had returned to Chicago as a professor.75 After a 13-year absence, Merrifield arrived in Yokohama with his team on May 4, and as he would recall, “Professor Abe, ‘Father of Baseball in Japan’ went to great expense of time and money to give us a perfect time for the five weeks we were there.”76 The players were then treated to “tiffin with Marquis Okuma and came thru with out [sic] a social error in their first meeting with nobility.”77 As for baseball, the Maroons had a strong squad with seven seniors on their roster, so they looked forward to the best-of-seven series against Waseda along with a four-game series with Keio, and for the first time, games against Tokyo Imperial University and Hosei University, as well as a match against Kwansei Gakuin, located in the heart of western Japan.78

On May 11 Tobita’s long-awaited rematch against Chicago finally got underway.79 After both teams scored a run in the first, the second inning saw the Maroons add two while Waseda added three to take a 4-3 lead. The Japanese stretched the advantage to 6-4 in the sixth inning; however, the visitors came back with two in the seventh and the game ended in a 6-6 tie when play was halted in the 12th by darkness.80 This was the closest Waseda had ever come to beating Chicago, yet the momentum didn’t carry over as the Maroons never trailed in the next game against their hosts, which they won 4-2.81 After giving up 10 combined runs in the two games, Tobita had lost confidence in his pitchers’ ability to contain the Americans and began to despair, but then Shukichi Matsumoto literally came out of left field and surprised his coach by saying, “Please let me pitch.”82

Paul Hinkle and Juro Ito, starting pitchers of the May 19, 1920 Chicago—Waseda game. (Rob Fitts Collection)

Matsumoto was a highly regarded pitcher while growing up in Osaka who suffered a shoulder injury that forced him off the hill before joining Waseda. Yet after studying Chicago’s batters for two games he told his coach he was confident he could get the job done. Knowing Matsumoto was never one to brag, Tobita agreed to let him take the mound, then watched him use superb control to allow only three hits in a shutout, while Herbert “Fritz” Crisler gave up two runs and took the loss.83 Tobita described it as an “extraordinary performance” that led to Waseda’s first-ever win over the Maroons, but the jubilation was short-lived as the Americans bounced back to beat Waseda in Osaka by a score of 3-1.84 The next day Tobita called upon Matsumoto again, and although he gave up two runs in the sixth and the tying run in the eighth, he kept the score tied for another four innings until Tokuyoshi Tominaga made a clever bunt to outsmart Chicago captain and catcher Clarence Vollmer and squeeze in the run that made it 4-3. Matsumoto then closed out Chicago in the bottom of the 14th, “achieving his second great victory.”85

In Kyoto on June 1, however, Chicago held off Tobita’s men to win, 4-3, then reasserted their dominance with an 8-1 blowout in Nagoya, so although Waseda’s long winless streak against the Maroons finally ended, they still lost the series.86 Meanwhile, Chicago barely squeaked by Keio 1-0 in 10 innings, was held to a 3-3 draw in another 10-inning affair halted by rain, and then was beaten in its two other meetings with Keio, 2-1 and 1-0, marking the first time the team lost a series to a Japanese opponent.87 In its other two Tokyo matchups, Chicago had little trouble beating Imperial University, 5-0, and defeated Hosei University 4-1, while in Kobe the Maroons outlasted Kwansei, 6-4.88 For Tobita, all this meant that Waseda still had a ways to go in relation to its two biggest rivals,89 while Merrifield in a tour recap acknowledged the progress Japanese baseball had made:

Needless to say, we did not play as well as Chicago teams of other years, and all the Japanese teams had apparently improved in the mastery of our game. We were fortunate indeed to win eight games, tie two, and lose only four. Several other games were nip and tuck, and a breath would have turned them the other way. With the full Spring and Summer practice we would doubtless have cleaned up the entire series, as our predecessors had done; but we had to make the best of a serious handicap against teams that played practically the year round. If they, in turn, play as well in their return game of 1921, they will give our American teams a bad time. … This exchange of international courtesies, this cultivation of wholesome and friendly athletic rivalry is good seed sown for a great future harvest of good will.90

For Waseda’s return tour in 1921, Abe accompanied Tobita and the team, which played in Hawaii and on the mainland en route to Chicago.91 The pitching staff became depleted due to injury and illness, so Tobita relied heavily on Goro “Iron Arm” Taniguchi, who lost, 4-2, in the first game vs. Chicago, but rebounded with wins over Northwestern and Page’s team at Butler, before tossing three innings of relief against Indiana.92 Iron Arm was sent out again for the rematch against Chicago, but after giving up four runs in six innings he pleaded to be relieved. Tobita wanted to send him back to the slab but was rebuked by Abe, who recognized that Taniguchi’s arm was wrecked.93

Clearly desperate, Tobita declared that he would suit up and take second base so that the ailing Matsumoto could move to the mound, but even though Page played during the Japan tour the previous year, Abe emphatically rejected this idea too. Tobita then reluctantly accepted a brave offer from shortstop Tadashi Kubota to step up to the mound, and although he gave up a run in the eighth, the first-time pitcher threw a scoreless ninth to keep Waseda close, allowing his team to respond with an amazing three-run rally to tie the game.94 Although Chicago retook the lead with two runs in the 10th, Waseda never gave up and fought back again for an incredible 8-7 win.95 Tobita later reflected, “The fierce battle turned out to be a bizarre victory for Waseda yet as Stagg Field was filled with cheers, Americans came down from the stands one after another to shake hands with us.”96

Four years later, with Merrifield now retired from coaching, Chicago was skippered by Nels Norgren, a former Maroon who as a freshman missed out playing against Waseda in 1911, but then coached the University of Utah in an 8-4 loss to the 1916 Konoled team.97 Since returning, Norgren had “topped off his career to date with the restoring of Chicago to Conference honors on the diamond in the Spring of 1925,” and now he had his own chance for redemption against Waseda.98

Far from deterred, Tobita’s mindset was fixed: no matter how elite the Maroons were, he couldn’t let them get away with the series this time.” With the opener taking place on a national holiday and Waseda’s ace Yoshikazu Takeuchi on the mound, it had all the makings of a Japanese fairy tale.100 It was a pitchers’ duel, and in the bottom of the ninth with one out, the bases loaded and down, 2-0, Tobita sent up a right-handed pinch-hitter, Sadayoshi Fujimoto.101 Lefty Joe Gubbins called for a towel to dry his sweaty hands, then proceeded to throw three strikes to sit Fujimoto down without a swing.102 Tobita then sent up right-handed pinch-hitter Eijiro Mizuno, who worked the count full, setting up a dramatic finish:

Joey started a wide hook that looked like it was headed about two inches wide of the plate. That would have been ball four and would have forced in a run, leaving the bases still full. But just before the ball reached the plate it hooked in and darted across a corner of the rubber. The umpire yelled “strike three,” and the dazed Mizuno, who had been all ready to start for first base had to chart his course along another tack. Nobody cared very much, however, just where Mizuno went, for a crowd of more than 20,000 was giving vociferous tribute to the courage and skill of Joey Gubbins. Joey, only 21 and modest, was looking for the quickest and most obscure route to the club house.103

Tobita had let the chance slip away, but he was determined not to lose to Chicago again. The rest of the Japanese teams also put up fierce competition against the Americans, as the next four games all ended in scoreless draws: a rain-shortened five-inning tie with Keio, two extra-inning games with Meiji halted by darkness, and a nine-inning rainout against Waseda.104 Norgren would later point out, “In order to keep their heads above water, both teams had to make perfect plays at the plate, double plays, brilliant catches and stops in the field.”105 The “jinx” was finally broken when in the second game against Keio, with the score tied, 2-2, in the ninth, shortstop Albert McConnell pulled off a daring squeeze play to send Bob Howell home for the winning run.106 Chicago and Waseda then played to a 1-1 tie in 10 innings, but Tobita’s men finally seized their first win of the series in the next game when Fujimoto shut out the Maroons, 1-0.107

The Americans then battled two professional teams, defeating Takarazuka twice but losing, 2-1, to Daimai in 10 innings, then traveled to Korea, where they easily notched five straight victories.108 While Chicago played in Seoul, Waseda and Keio faced off for the first time in nearly 20 years with a doubleheader kicking off the new Tokyo Big Six Baseball League.109 In the opener, Waseda’s Yoshikazu Takeuchi had a perfect game broken up in the ninth en route to an 11-0 win. Fujimoto followed that performance by allowing only one run in a 7-1 decision to complete the two-game sweep of Keio.110

Abe was surely proud of his team for capturing the first real Japanese baseball championship since 1906, but for Tobita it didn’t really matter, for in his mind Waseda’s biggest foe was still Chicago.111 While “in Korea the team seemed to find its batting eye,” and when Chicago returned to Japan they continued their hot hitting, beating Montetsu 14-0 and the Fukuoka All-Stars 12-3.112 Norgren’s pitchers had taken their play to the next level, too, as Gubbins threw a no-hitter in Kyoto backed by 14 runs to turn the tables against Daimai. William Macklind followed that with a one-hitter in a 6-0 win against a team from Nagoya in Chicago’s last game outside of Tokyo.113

The Maroons thus returned to the capital for their final game of the tour, which as fate would have it was also to be the decisive match of the Waseda series, now deadlocked at 1-1-2.114 Norgren selected Gubbins, who was well rested after his no-hitter, while the obvious choice for Tobita was Takeuchi, who after his near-perfect game against Keio went on to beat Hosei and shut out the powerful Meiji team.115

The winner-take-all matchup between Waseda and the University of Chicago had all the makings of a pitchers’ duel; however, when the game got underway in front of a capacity crowd packed into the newly built stands at Totsuka Stadium, “The Maroon team started with a rush and scored four runs.”116 It was clear Takeuchi didn’t have it that day, meanwhile Gubbins’ fastball was so good that it seemed Waseda was surely doomed.117 If they lost the series yet again, Tobita knew it would mean another long wait for a chance at redemption, and he doubted if “in the fever of a broken heart, it would be possible to endure another five years.”118 So Tobita pulled Takeuchi and replaced him with Fujimoto, then stared at the ground frozen with grief.119

But in the bottom of the fifth Waseda’s luck started to change, as the number-seven hitter, Toshinobu Yasuda, swung at the first pitch he saw from Gubbins and hit a blooper into right field.120 When Fujimoto followed this with a single past second, Norgren figured Waseda’s number-nine hitter was going to bunt so he adjusted his infield accordingly.121 Tobita recognized the trap, so he called Yukisato Nemoto over before he entered the box and told the left-hander to look for an inside pitch to pull.122 Nemoto stepped to the plate and prayed for a changeup but got a fastball instead, yet somehow he still managed to turn on it and sent the ball “like a meteor through space” until it skimmed the outfield fence, scoring Yasuda and putting Fujimoto on third while Nemoto made it into second with a double.123 Takehiko Yamazaki then belted a triple to right that pulled Waseda within one, but Gubbins finally settled down and got out of the inning.124

Entering the seventh, Norgren lifted his southpaw in favor of Macklind. The righty gave up a double to Shinjiro Iguchi and issued a walk to Kimitsugu Kawai.125 With the right-handed Fujimoto due up, Tobita was faced with a tough decision: let his pitcher bat, or bring in a left-handed pinch-hitter. Although Fujimoto blew his chance by taking three straight strikes from Gubbins in the first game of the series, Tobita elected not to make a change, and what a decision this turned out to be, as Fujimoto took Macklind deep with a three-run homer over the center-field fence.126 Waseda added to its lead in the eighth with Yamazaki sending one over the right-field wall, clouted its way to a 10-4 victory, and in the process won a series against the Maroons for the first time.127

It was a historic season in which Waseda swept Keio in the first Sokei-sen fought in nearly two decades, then beat Hosei, Meiji, Rikkyu, and Imperial to secure the first Tokyo Big Six Baseball League championship. But looking back, Tobita would say that despite all this, “beating Chicago had a different flavor.”128 His players weren’t as thrilled as they had been when they defeated Keio and Meiji, and the fans didn’t seem as happy either, but Tobita went home in a dreamy state, and as he held his two children in his arms, tears rolled down his cheeks.129 He thought to himself, “I had done what I had to do,” believing his steep debt to the Waseda team and to his mentor, Abe, was at least partly repaid.130 So the next day, without telling his wife his intentions, Tobita met with Abe and tendered his resignation.131 His manager stared at him for a while, and then said, “I’ll discuss it with my seniors.”132 But as much as Tobita respected Abe, he knew his decision could not be reversed, no matter what the circumstances, so he gathered his players on the first-base bench to say goodbye:

I was so full of gratitude that hot tears fell harshly on the players as I shook hands with each of them. They all hung their heads except one, Takeuchi, who said, “It’s still good, don’t you want to do more?” He sounded as if he was giving me an order in a ridiculous voice full of Kyoto dialect. Then as soon as I crossed the threshold at home, I said, “Hey, I quit coaching today.” As expected, my wife looked a little surprised, but [my children] Tadahiro and Chuei suddenly shouted ‘Banzai.’”133

The Maroons, despite losing their series to Waseda, returned home with a record of 19 wins, 8 losses, and 5 ties. Norgren would have to wait longer than expected for a rematch since Waseda decided to postpone its return tour until 1927. By then Waseda had a new coach, Tadao Ichioka, who was a catcher when Waseda hosted Chicago in 1915.134 After the teams split two games, Norgren was redeemed as the Maroons clinched the 1927 series with a 9-3 win in the finale.135

Three years later, Norgren prepped his team for its 1930 Japan tour by playing 13 games while en route to Seattle, from where they set sail on August 20.136 The coach later recalled, “Without exception, the boys played a class of ball that was encouraging when one contemplated the approaching contests in Japan.”137 By the time the Maroons arrived at Yokohama, Abe had retired from Waseda and was elected to the Diet in 1928, literally and figuratively getting off the sidelines in an attempt to stem the tide of militarism and advance a social democratic agenda.138 Yet there were still two familiar faces to greet Norgren at the port, as both coach Ichioka and manager Takasugi were still with the team.139 After taking the electric tram to Tokyo, Norgren and his squad of a dozen players were greeted with a rousing welcome from the Waseda students and then spent a half-hour posing for pictures and being filmed alongside the Japanese team.140

Chicago was to play two games apiece against Waseda, Keio, and Meiji at Jingu Stadium, with a capacity of 50,000, as well additional games vs. Waseda and other teams outside Tokyo.141 In the opener, Chicago and Waseda both scored three runs in the first three frames, after which the Japanese scored five more runs and held on to win 8-5.142 Then, as Norgren later recalled, “The going was hard! We were defeated in the next four games, by Waseda, 8 to 3, Keio, 4 to 2, and Meiji, 10 to 5, and 6 to l.”143 Chicago finally won its first game of the tour when it bettered Keio, 2-1, but fell again to Waseda 7-6 in Yokohama.144 Everything began to change, however, once the Maroons reached Takarazuka, where they outlasted Waseda, 6-4, in 10 innings, then beat them again the next day, 4-1.145 Chicago went on to beat Kwansei, 6-4, and twice defeated Waseda’s alumni, 3-1, and 4-1, before tying the Tokyo Club, composed of all-star collegiate graduates, 1-1, in 12 innings.146

One last game was to be played against Waseda in front of a large crowd in Maebashi, about four hours north of Tokyo, where Chicago completed its turnaround by beating its hosts, 4-1, and in the process clinched a series split with Waseda.147 This was followed by a finale against the Waseda alumni who up to this point had never beaten Chicago, but this time the “old boys” finally broke through, scoring a run in the ninth to win 5-4.148 Norgren later shared his reflections on the tour:

After being completely snowed under in the first five games of the series, the boys fought their way out from underneath and finished with a record of seven victories, seven defeats, and one tie. We broke even with Waseda and Keio, but Meiji holds two victories over us.

Five years ago I thought the popularity and the development of baseball in Japan had reached its peak. I found that in five years there was considerable growth in the popularity of baseball as well as in the proficiency of the teams. The keen rivalry which results in close games between the six teams of the University League in Tokyo has taken the fancy of fans, and their interest is greater in this series than it is in any series with a foreign team. While games with American college teams sometimes bring out crowds of about 25,000 spectators, the crucial games between the Tokyo universities has [sic] been known to attract a throng of 40,000 to 50,000 people. In the case of the championship series in the fall of 1929 between Waseda and Keio, they had a sell-out for both games which meant between 50,000 and 60,000 people. Naturally, such interest is due to the keen rivalry developed through the proficient performance of the members of the league. There is no doubt in my mind that only a champion college team can hope to win more than half of its games against Waseda, Keio, and Meiji Universities, as they are playing ball today. The day is past when a college team can make a clean sweep of the series in Tokyo, unless it is a team of unusual calibre.149

For reasons not entirely clear, there was no return tour in 1931 and although Chicago had been traveling to Japan every five years since 1910, there was no tour in 1935, but Chicago once again welcomed Waseda back to the Midway in May 1936.150 Now coached by Kyle Anderson, who was the leadofif hitter on Norgren’s 1927 squad, Chicago rocked Shozo Wakahara and withstood a late rally to win 18-16.151 The Japanese ace bounced back, striking out 17 in a 10-5 victory, then followed that with a no-hitter against Yale, but he failed to repeat his heroics in the rubber match with Chicago, as the Maroons routed Waseda and took the series with a 13-3 win.152 That was the last time the two teams met for more than 70 years, so when Chicago finally returned, it truly marked the restart of a legendary rivalry.

Before taking the field on Easter Sunday in 2008, the Maroons donned suits while Waseda wore their student uniforms to attended Mass at Noboricho Cathedral, and then both teams paid their respects at Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park.153 Some of the Chicago players were familiar with their university’s role in the development of the atomic bomb. (Manhattan Project scientists created the world’s first nuclear reactor inside a makeshift laboratory built beneath the stands at old Stagg Field.)154 Ahead of the trip, Maroon southpaw Nathan Ginsberg discussed the Chicago-Hiroshima connection with a reporter, yet noted, “As important as that is and as tough as it may be to concentrate, we want to go out and win a few games.”155 Indeed, most of the media attention focused on the history of the baseball rivalry itself, with pitcher Payton Leonhardt saying, “It has hit home with us that this is a tradition that has dated back far more than we can comprehend. That is what is driving us.” Co-captain and outfielder Mike Serio added, “Every decision made, and every play we have, in the back of everyone’s head is that we have to win in Japan,” while co-captain and first baseman, Dominik Meyer admitted, “We will try to do our best and not embarrass ourselves.”156

In the opener at Hiroshima Municipal Stadium, the Maroons were, in fact, embarrassed, losing 15-0 in front of some 14,000 fans. After Waseda’s lopsided victory, a reception was held at which dignitaries praised the visitors, not for their performance that day, but for the historic role their school played both in the evolution of Waseda’s team as well as baseball throughout Japan.157 In the next game, played under the lights in the Osaka Dome, Serio scored his team’s first run of the series, but Chicago was held scoreless the rest of the way while Waseda’s up-and-coming batters scored six runs in the final three innings for an 8-1 win.158

Ahead of the finale at Seibu Dome, just outside Tokyo, Wasaburo Yawata, son of right fielder Kyosuke Yawata, who played against Chicago during Waseda’s 1911 tour, presented flowers to Waseda coach Atsuyoshi Otake, while Junko Kuwano and her daughter Kiyoko presented a bouquet to Chicago coach Brian Baldea.159 Junko’s father was Goro Mikami, left fielder on Waseda’s 1910-1911 tours, who after graduating from Waseda played in the United States for Knox College and then professionally for the barnstorming All Nations club.160 A reporter noted at the time, “If this news is flashed around among the ball playing universities it ought to do more to cement peace and promote international good feeling than the tracts which are being scattered by many of the Japanese-American organizations.”161

So as Junko watched along with Kiyoko and Wasaburo at her side, the Waseda team looked to secure its first ever series sweep of the Maroons on either side of the Pacific.162 Then just as Merrifield prophesied over a hundred years before, the Japanese players proceeded to hit the American curves and made their share of the fun while on their way to a 10-0 victory, after which they bowed politely to the umpire.163

CHRISTOPHER FREY is a writer, director, and producer at Cross Media International, a production company based in San Francisco and Tokyo that he co-founded in 2003. While earning degrees in Asian studies and diplomacy and world affairs with a minor in Japanese from Occidental College in Los Angeles and the International Program at Waseda University in Tokyo, he was awarded a Richter International Fellowship for research conducted in Hong Kong and Southern China, as well as an Anderson Fellowship for research conducted at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. In 1988 Chris attended his first professional baseball game in Japan as the Hiroshima Toyo Carp hosted the Yakult Swallows, then 20 years later was at Tokyo Dome to see his hometown Oakland Athletics take on the Boston Red Sox in the 2008 edition of the MLB Japan Opening Series.

NOTES

(Article titles originally in Japanese have been translated into English)

1 “Opening Series Japan 2008,” mlb.com/mlb/events/opening_series/y20o8/; Jodi S. Cohen, “Honoring Old Rivalry a World Away,” Chicago Tribune, March 15, 2008: 1-2.

2 David Hilbert, “Chicago Baseball to Tour Japan,” Uchicago.edu, February 15, 2008. http://athletics.uchicag0.edu/news0708/bb-waseda-021408.htm.

3 Waseda Alumni Club, “Restart of Legend: Waseda University vs. the University of Chicago,” Tokyo, NTT Quaris, 2008: 3.

4 Ernest Wilson Clement, “Duncan Baptist Academy,” American Baptist Missionary Union Ninety-First Annual Report (Boston: Missionary Rooms, 1905), 276-277.

5 Suishū Tobita, Fifty-Year History of the Waseda University Baseball Club (Tokyo: Waseda University Baseball Club, 1950), 74-91.

6 Waseda University, Centennial History of Waseda University: Volume II (Tokyo: Waseda University Press, 1990), 146.

7 Waseda University, 149.

8 Fred Merrifield, “Love Baseball in Japan,” Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1905: 9.

9 “Base Ball Team: 1900,” Cap and Gown: Volume VI (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1901), 218-221; They Went to Japan: Biographies of Missionaries of the Disciples of Christ (Indianapolis: United Christian Missionary Society, 1949), 29-30; “Religious and Charitable,” Pittsburgh Press, October 26, 1907: 5.

10 “Athlete as Missionary: Rev Alfred W. Place to Introduce Baseball and Football to Students of Japanese Universities,” Boston Globe, October 28, 1907: 5.

11 Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 107, 113; “Certified Copy of the Registration of an American Citizen at the American Consulate-General, Yokohama, Japan,” Deputy Consul General of the United States of America, January 20, 1911.

12 >David E. Sumner, Amos Alonzo Stagg: College Football’s Greatest Pioneer (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2021), 149.

13 “Maroon Nine to Visit Japan,” Chicago Tribune, June 19, 1910: 23.

14 Sumner, 149; “Maroons May Learn Tricks,” Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1910: 10.

15 J.J. Pegues, “International Baseball,” Independent, January 19, 1911: 70; Gerald R. Gems, The Athletic Crusade: Sport and American Cultural Imperialism (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006), 36; “Miss Anna H. Marshall Becomes Wife of Fred Merrifield at Home Wedding,” Rock Island Argus, September 5, 1907: 5.

16 Pegues, 70-71.

17 H. Orville Page, “Maroons on Trip of 19,000 Miles,” Chicago Tribune, August 28, 1910: 25; “Undergraduate Life: The Japanese Trip,” University of Chicago Magazine 3 no. 1, (1910): 50; Pegues: 70.

18 Robert W. Baird, “The Longest and Most Successful Baseball Trip of All Time,” University of Chicago Magazine, Autumn 1976: 56-59.

19 Pegues: 71-72.

20 Pegues: 71-72.

21 Pegues: 72.

22 H. Orville “Pat” Page, “Maroon Team Guests of Japs,” Chicago Tribune, October 30, 1910: Sec. III, 4; Gilbert A. Bliss, “Bliss Writes Story of Arrival In Japan,” Daily Maroon, October 28, 1910: 1-3; Katarzyna Joanna Cwiertka, Modern Japanese Cuisine: Food, Power and National Identity (London: Reaction Books, 2006), 14-15.

23 Page, “Maroon Team Guests.”

24 Page, “Maroon Team Guests.”

25 Page, “Maroon Team Guests.”

26 Pegues: 72.

27 Pegues: 72.

28 “International Base-Ball Match at Waseda University, Ushigome, Tokyo,” Gurahikku (The Graphic) 4, 1910: 233.

29 Waseda University, 575.

30 “International Baseball Match at Waseda,” Japan Times, October 5, 1910: 6.

31 “International Baseball Match at Waseda;” “Invasion of the East,” Cap and Gown: Volume 16 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1911), 12.

32 Pegues: 72.

33 Pegues: 73.

34 “International Baseball Match at Waseda,” Japan Times, October 5, 1910: 6.

35 “International Baseball Match at Waseda,” Japan Times, October 5, 1910: 6.

36 “International Baseball Match at Waseda,” Japan Times, October 5, 1910: 6.

37 “International Baseball Match at Waseda”; Pegues, 73.

38 “The Supporters of Waseda,” Gurahikku (The Graphic) 4, 1910: 217; “International Base-Ball Match at Waseda University: 251; Yujiro Koike and Yuko Kusaka, “The Theory of Human Building of Tobita Suishu in Baseball,” 74. https://rose-ibadai.repo.nii.ac.jp/?action=pages_view_main&active_action=repository_view_main_item_detail&item_id=i7522&item_no=i&page_id=i3&block_id=2i; Suishu Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball: History of Japanese Baseball in the Early Days (Tokyo: Chuo Koron Shinsha, 2005), 353-354.

39 “International Baseball Match at Waseda,” Japan Times, October 9, 1910: 2; H. Orville “Pat” Page, “Page Writes of Conquests,” Chicago Tribune, November 2, 1910: 11.

40 “International Baseball Match at Waseda,” Japan Times, October 7, 1910: 6; “Invasion of the East,” 12-13; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 119: H. Orville “Pat” Page, “Clean Sweep for U. Of C. Ball Team,” Chicago Tribune, November 16, 1910: 10.

41 H. Orville “Pat” Page, “Page Tells of Japan Trip,” Chicago Tribune, December 28, 1910: 8; “Invasion of the East,” 12.

42 Page,“Page Tells of Japan Trip.”

43 Page,“Page Tells of Japan Trip.”

44 H. Orville “Pat” Page, “Japs Treated to Real ‘Thrillers,’” Chicago Tribune, November 22, 1910: 14; “Page Tells of Japan Trip.”

45 “Maroon Nine Continues Victories Over Japs,” Chicago Tribune, October 28, 1910: 11; Page, “Japs Treated to Real ‘Thrillers’.”

46 “Return from Japan,” University of Chicago Magazine 3, Number 3, January 1911: 167.

47 “Return from Japan.”

48 “Return from Japan.”

49 “International Base-Ball Match at Waseda University: 233.

50 Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 118; Waseda University, 577; Koike and Kusaka, 74.

51 Koike and Kusaka, 72-74; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 96; Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 353-354.

52 “Abe Resigns as Waseda Manager,” Honolulu Advertiser, April 1, 1911: 3; “Waseda Baseball Team Will Tour the United States,” Japan Times, March 9, 1911: 6.

53 “Japanese Team Tour Schedule Given Out,” Washington Times, April 8, 1911: 11.

54 “Professor Abe Lectures,” Daily Palo Alto, May 1, 1905: 6; Robert K. Fitts, Issei Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 57.

55 Shin Hashido, Recent Baseball Techniques (Tokyo: Hakubunkan, 1905), 199-208; Sheng-Lung Lin, “The Development of the New Bushido Yakyu Culture,” Journal of Physical Culture 16, December 2014: 49-104.

56 >Hashido, 199-208; Lin.

57 “Baseball and Peace,” Chicago Tribune, March 29, 1911: 6.

58 “Jap Ball Team Arrives Today,” San Francisco Call, April 13, 1911: 13; “American Tour of Waseda University (Japan) Team,” Official College Base Ball Annual for 1912 (New York: American Sports Publishing, 1912), 23-27.

59 “‘Pat’ Page Gains Bride in Athletic Romance,” Chicago Examiner, June 15, 1911: 2; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 122-123.

60 “Chicago Team Coming, Some Lively Games Expected by Local Nines,” Japan Times, August 14, 1915: 5.

61 Waseda University, 1070; “20,000 Japs See Ball Game,” New York Times, September 25, 1915: 13; H. Orville “Pat” Page, “Maroons Score Two Shutouts; Win Seven Straight in Japan,” Chicago Tribune, November 13, 1915: 11; H. Orville “Pat” Page, Baseball Tour of the Far East,” Cap and Gown: Volume 21 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1916), 273-275; Tobita, Fifty-Year Histoy, 139-140.

62 H. Orville “Pat” Page, “Maroon Nine Sweeps Series; Wins Ten Straight in Japan,” Chicago Tribune, November 16, 1915: 11.

63 John Husar, “Baseball in 1915: Have Yen, Will Travel,” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1973: Sec 3, 1.

64 “20,000 Japanese Fans Saw Chicago Varsity Team Win,” Boston Evening Globe, September 24, 1915: 7; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 14-23.

65 H. Orville “Pat” Page, “Japan Greets Maroon Team with Spirit,” Chicago Tribune, October 24, 1915: 23; “20,000 Japanese Fans Saw Chicago Varsity Team Win.”

66 Cap and Gown: Volume 22 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1917), 276-278.

67 Waseda University: Volume III: 517.

68 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 352-355.

69 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 355-360

70 Koike and Kusaka, 74.

71 Lin, 49-50.

72 Robert Whiting, You Gotta Have Wa (New York: Collier Macmillan, 1989), 38-39.

73 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 375.

74 Koike and Kusaka, 74.

75 “Pat Page Quits as Maroon Coach,” Quad City Times, February 11, 1920: 21; “Dozen Maroons Named for Ball Tour of Orient,” Chicago Tribune, April 2, 1920: 13.

76 Fred Merrifield, “1920 Baseball Team in Japan,” Cap and Gown: Volume 26 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1921), 411.

77 Ted Curtiss, “High Spots on the Japan Trip,” Cap and Gown: Volume 26 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1921), 413.

78 “The Baseball Schedule and Scores of the Games Played in Japan, 1920,” Cap and Gown: Volume 26 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1921), 410.

79 Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 167.

80 “U. of Chicago Plays 6-6 Tie with Waseda College,” Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1920: 12; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 167.

81 Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 168.

82 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 290.

83 Tobita, ‘Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 290-291.

84 “The Baseball Schedule and Scores of the Games Played in Japan, 1920.”

85 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 291.

86 “Chicago University Baseball Nine Defeated Waseda at Kyoto,” Japan Times and Mail, June 3, 1920: 8; “The Baseball Schedule and Scores of the Games Played in Japan, 1920.”

87 “Chicago Wins Fast Ten Innings Game,” Times and Mail, May 15, 1920: 1; “Keio Nine Holds Chicago to Tie,” Japan Times and Mail, May 22, 1920: 8; “The Baseball Schedule and Scores of the Games Played in Japan, 1920.”

88 “The Baseball Schedule and Scores of the Games Played in Japan, 1920.”

89 Tobita, ‘Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 292-293.

90 Merrifield, “1920 Baseball Team in Japan,” 411.

91 Tobita , Fifty-Year History, 176-182.

92 James Crusinberry, “Japs Play Well, But Batina Whisper, So Maroons Win, 4-2,” Chicago Tribune, May 11, 1921: 18; “Maroons Win from Japanese Ball Team,” Decatur (Illinois) Herald and Review, May 11, 1921: 4; “Japanese Win By 17 to 1,” New York Times, May 12, 1921: 14; “Japs Nose Out Butler, 2 to 1,” Indianapolis , May 15, 1921: 25, 35; Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 61; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 182.

93 “Japs Nose Out Maroons,” Quad City Times, May 19, 1921: 7; Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 61-62.

94 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 63-65; “Japs Nose Out Maroons”: 7.

95 “The Waseda Series,” Cap and Gown: Volume 27 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1922), 377; Tobita, Thirty Years, 65-66; “Japs Nose Out Maroons,” 7.

96 Tobita, ‘Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 66.

97 “Japanese Team Displays Real Diamond Class,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, May 13, 1916: 15; “Cal’s Comments,” Green Bay Press Gazette, September 10, 1921: 5.

98 “The Baseball Coach,” Cap and Gown, Volume 31 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1926), 409.

99 Tobita, ‘Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 386-387.

100 “The Japanese Trip,” Cap and Gown: Volume 27 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1926),415.

101 “Maroons Beat Waseda, 2-0,” Chicago Tribune, September 24, 1925: 21; Luther A. Huston, “20,000 Tokyo Fans Cheer as Chicago Boy Fans Man with Bases Full in Ninth,” Tampa Tribune, November 2, 1925: 11; “Japanese Trip,” Cap and Gown: Volume 31 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1926),415.

102 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 386-387; “Maroons Beat Waseda, 2-0,” 21; “Huston.

103 Huston.

104 “Fourth Called Game for Chicago Maroons,” Honolulu StarBulletin, October 6, 1925: Sec. II, 9; “Maroons and Waseda U. Nines Play Scoreless Tie,” Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1925: 26; Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 386-387; “The Japanese Trip,” 415.

105 Nels Norgren, “The Japan Trip, The Seventh International Baseball Series,” The University of Chicago Magazine, VOL. XVIII NO. 3, January 1926: 114.

106 “The Japanese Trip,” 416.

107 “U. Of C. Nine Like Grid Team; Plays to a Tie,” Chicago Tribune, October 13, 1925: 30; “The Japanese Trip,” 416; “Maroons Lose to Waseda,” Chicago Tribune, October 14, 1925: 32; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 250;

108 “The Japanese Trip,” 416-417.

109 Waseda, Centennial History, V. III: 517-525.

110 “Keio Loses First Tilt of Japan’s Big Series,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 20, 1925: 6; Waseda, Centennial History, V. III: 517-525.

111 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 386.

112 >“The Japanese Trip,” 417.

113 “The Japanese Trip,” 417.

114 “The Japanese Trip,” 417.

115 Tobita, Thirty Years, 116.

116 “The Japanese Trip,” 417.

117 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 116.

118 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 387.

119 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 117.

120 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 326.

121 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 327.

122 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 327.

123 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 327.

124 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 328.

125 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 328.

126 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 327-328.

127 “The Japanese Trip,” 417; Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 328.

128 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 328.

129 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 388.

130 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 388.

131 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 388.

132 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 388.

133 Tobita, Thirty Years of Hot Ball, 388.

134 “Japanese Team Displays Real Diamond Class”: 15; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 266.

135 “Chicago Nine Scores Win Over Waseda Team,” Wisconsin State Journal (Madison), June 2, 1927; “Waseda Evens Series; Beats Maroons,” Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1927; “Maroons Beat Waseda,” Chicago Tribune, June 8, 1927: 23; Tobita, Fifty-Year History: 266-267.

136 Nelson H. Norgren, “Japan Trip,” Cap and Gown: Volume 36 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1931), 182.

137 Norgren, “Japan Trip,” 182.

138 “Politics as Practiced in Orient Will Be Detailed by Speaker at Men’s Meeting,” Mansfield (Ohio) News-Journal, January 15, 1928: 5.

139 Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 298-304; Abe Resigns as Waseda Manager,” Honolulu Advertiser, April 1, 1911: 3.

140 Nelson H. Norgren, “Ninth International Baseball Series,” University of Chicago Magazine, December 1930: 71.

141 Norgren, “Ninth International Baseball Series”: 72.

142 Norgren, “Japan Trip,” 183.

143 Norgren, “Ninth International Baseball Series”: 73.

144 “Maroon Ball Nine Loses to Waseda University, 7-6,” Chicago Tribune, September 16, 1930: 24; Norgren, “Ninth International Baseball Series”: 74; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 304.

145 “Chicago Beats Waseda,” New York Times, September 21, 1930: S6; Norgren, “Ninth International Baseball Series”: 74; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 304.

146 Norgren, “Ninth International Baseball Series,”: 74; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 304.

147 Norgren, “Ninth International Baseball Series”: 74; Tobita, Fifty-Year History, 304.

148 Norgren, “Ninth International Baseball Series”: 74.

149 Norgren, “Japan Trip,” 185.

150 “Maroon Diamond Squad Faces Waseda University in Three Game Series Opening Friday,” Daily Maroo, May 27, 1936: 4; “Waseda Is Due Tomorrow for Maroon Series,” Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1936: 22.

151 “Maroon, Waseda Teams Split Two Weekend Games,” Daily Maroon, June 2, 1936: 4.

152 “Maroons Defeat Waseda 13 to 3 to Win Series,” Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1936: 24; Tobita, Fifty-Year History: 383-384; “Maroons, Waseda to Play Deciding Game Tomorrow,” Chicago Tribune, June 16, 1936: 24; “Japanese Pitcher Hurls No-Hitter Against Yale,” Scranton Tribune, June 9, 1936: 15.

153 “Baseball: Japan 2008 Blog,” University of Chicago, edu, March 25, 2008. https://athletics.uchicago.edu/about/history/travel_blogs/baseballjapan_20o8_blog.

154 David N. Schwartz, “What It Was Like to Witness the World’s First Self Sustained Nuclear Chain Reaction,” Time magazine, December 1, 2017.

155 >Joe Lombardi, “Have Bat, Will Travel (Japan) Ex-Dobbs Ferry Standout Also Pitches for Chicago Squad,” White Plains (New York) Journal News, March 18, 2008: 23.

156 Cohen, “Honoring Old Rivalry a World Away”: 1-2.

157 “Baseball: Japan 2008 Blog.”

158 Jodi S. Cohen, “U. of C. Team Wins Fans, but No Games, in Japan,” Chicago Tribune, April 4, 2008: 2-8; “Baseball: Japan 2008 Blog.”

159 Junko Kuwano, daughter of Goro Mikami, email correspondence, February 2022; “Baseball: Japan 2008 Blog.”

160 “Japanese Baseball Player Captain of College Team,” Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1915: 23; Kuwano; “Japan Tour 2008.”

161 “Jap Will Lead Knox College Team,” , April 17, 1915: 8.

162 Kuwano.

163 “Waseda University 125th Anniversary Exchange Game March 25 at Seibu Dome,” Waseda Sports, March 25, 2008; Kuwano; “Baseball: Japan 2008 Blog.”