Herb Hunter’s Dream Tour: A Rabbit, Two Leftys, and an Iron Horse Visit a Dangerous Japan in 1931

This article was written by Dennis Snelling

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

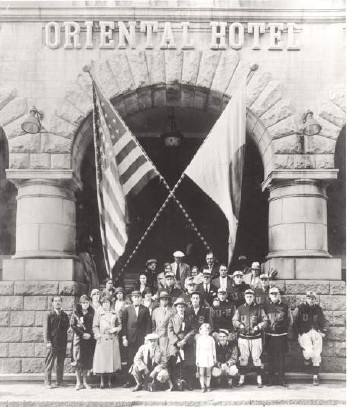

1931 All-Americans in front of the Oriental Hotel in Kobe (National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, NY)

It was a tour initially framed by the dreams of retired fringe major-league outfielder Herb Hunter, the continuing quest of a Japanese newspaper publisher to bring Babe Ruth to Japan before he retired as a player, and the metastasizing of Japanese militarism.

The tour ended with the best baseball team to visit Japan up to that time—including seven future Hall of Famers—winning all 17 games they played in the country, Japan’s political landscape in violent disarray, Babe Ruth still not having visited the country, and the beginning of the end of Herb Hunter’s global baseball aspirations.

By 1931, Hunter was considered “Baseball’s Ambassador to Japan.” He had first crossed the Pacific Ocean 11 years earlier with a group of minor-league and marginal major-league players. During that trip, Hunter partnered with pitcher Charlie Robertson to earn money on the side, coaching the Waseda University baseball team.1

Hunter developed an affinity for the country— and the potential it offered him to make his mark on the baseball world—returning in 1921 to coach the baseball teams of both Waseda and Keio universities, wearing a chrysanthemum in his lapel each day.2 The San Francisco Chronicle reacted to this news by derisively challenging its readers to visualize the ex-San Francisco Seals outfielder coaching baseball to anyone, since Hunter’s reputation was that of the proverbial million-dollar athlete with a ten-cent head. He was physically gifted, but legendary for his onfield blunders.3

He once executed an outstanding running catch with the bases loaded and one out in the ninth, only to absent-mindedly exit for the clubhouse, oblivious to the fact that the ball was still in play.4 On another occasion, with two out and the bases loaded, he decided to showboat on an easy fly, making a one-handed swipe at the ball, which he dropped. Three runs scored.5

It was said that Hunter had once nearly spiked himself dodging a line drive. “He played that ball like a camel,” the account went. “He was not hurt but he had a narrow escape. A lot of runs scored while Herbie was untangling himself.”6

Even when Hunter’s efforts won a game, it sometimes resulted from a bonehead move. He stole home in a game against Portland on a 3-and-0 count and two runners on base. He was called safe, his run the eventual game-winner despite the fact that he never touched home plate, not to mention that during the play the shocked hitter had backed into the catcher, which should have been ruled interference. Al C. Joy of the hometown San Francisco Examiner wrote, “Just why he stole home at that particular moment nobody seems to know. And just why Umpire Casey did not call him out for several reasons nobody seems to know.”7

Despite his shortcomings, Hunter’s connections to Japanese universities enabled him to organize a troupe of major leaguers to Japan in 1922, and make several subsequent visits, including in 1928, when he enlisted Ty Cobb, Bob Shawkey, and Fred Hofmann. Hunter was now ready to bring another team of major-league all-stars to the Orient in 1931.

But he was not to be wholly in charge of the effort. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, mindful of the international implications of such an event, and noting Hunter’s checkered success with past ventures—especially when it came to handling money—permitted the tour to proceed only under the supervision of veteran sportswriter Fred Lieb.8

Hunter acquiesced—he had no choice—and once the tour was approved by major-league owners in mid-January, he prepared to finalize arrangements with Japan’s largest newspaper, Mainichi Shimbun9

Catching wind of Hunter’s intentions, Matsutaro Shoriki, publisher of the rival Yomiuri Shimbun, intercepted him, ultimately persuading the American to award his newspaper exclusive sponsorship of the tour’s Tokyo segment. When Mainichi Shimbun backed out of sponsoring games in other parts of the country, Shoriki stepped in despite the added, and significant, financial burden, gambling that the event would put his publication on the map.10

Arrangements complete, Hunter returned to his home in Red Bank, New Jersey, where he managed a semipro team headquartered on his diamond, Hunter’s Field, while Fred Lieb pursued ballplayers for the trip.11

A 14-man roster was ultimately secured, including four 1931 World Series participants: A1 Simmons, Mickey Cochrane, Lefty Grove, and Frankie Frisch.12 To Shoriki’s disappointment there would be no Babe Ruth—who claimed barnstorming and movie commitments—but Ruth’s teammate and co-American League home run champion Lou Gehrig would be there. So would Willie Kamm, Rabbit Maranville, Muddy Ruel, George Kelly, Lefty O’Doul, Larry French, and Tom Oliver. Boston Braves pitcher Bruce Cunningham, a right-hander who had won only three of 15 decisions in 1931, and outfielder Ralph Shinners, who was just completing his career in the International League, rounded out the roster.

Fred Lieb had thought the All-Stars unbeatable— although they did not start out that way.

The team initially gathered in California in early October for a series of games in the Bay Area, and lost four of five against lineups composed almost entirely of Pacific Coast League players.13 The third game, against the San Francisco Seals, proved the most embarrassing. Lefty Grove, who arrived after the first two games along with the other World Series participants, took the mound and was battered for six runs in the first inning. The All-Stars began pointing fingers, with Grove loudly complaining about not having enough time to warm up. The left-hander settled down, shutting out San Francisco from the second inning through the fifth and striking out seven. But the All-Stars lost, 7-4, while collecting only four hits.14

Stateside exhibitions complete, the All-Stars boarded the luxury liner Tatsuta Maru for Japan; ship captain Shunji Ito, a talented golfer, accommodated the Americans by converting his deck-side course into a batting cage.15 On the way, there was a quick stop in Honolulu to play another tune-up game against locals.

During the brief sojourn in Hawaii, the team slaughtered a group of local semipros, 10-0, before 12,000 fans—many of them arriving from other islands.16 The famously dour Grove displayed uncharacteristic enthusiasm afterward, declaring himself enamored with Hawaii and musing, “.. .wonder what my chances are of buying a small place here, I can use this old sunshine in January and February.”17

While the All-Stars cavorted in paradise, events in Asia were unfolding at a dramatic and dangerous pace. A month before the players’ departure for Japan, a renegade faction of the military, seeking war with China, destroyed a section of the South Manchuria Railway and blamed it on the Chinese. This contrivance provided the pretext for Japan to invade Manchuria; the Japanese government was caught off-guard by its own armed forces, but did nothing of consequence to curtail the action, and was widely condemned in the court of world opinion. As a result, the country the American ballplayers entered was far more dangerous and unstable than they appreciated.

Thousands of enthusiastic Japanese baseball fans were on hand when the Tatsuta Maru docked following its two-week passage. After the mayors of Yokohama and Tokyo made brief presentations, the players boarded a special train bound for the capitol. There, the party was met by limousines waiting to convey them through the streets of downtown Tokyo.

Fred Lieb described the journey “a continual ovation.” Special flags combining the emblems of the American and Japanese national banners were provided to those lining the route. Fans jammed the streets, pressing in on the motorcade as shouts of “banzai” and “welcome” rained down from office windows. Some of the more enthusiastic jumped onto limousine running boards to shake the hand of Rabbit Maranville or Lefty Grove—repeatedly shouting “Thirty-One!” at the latter in recognition of his total wins for Philadelphia that year.18

The Americans were flabbergasted. “I will remember this reception to my dying day,” remarked Lou Gehrig. “I do not know of anything in my entire career that has touched me as much as this welcome.” Frankie Frisch added, “It made me feel like a great military hero or a man who had flown across the Pacific.”19

Other than George Kelly, who had been a member of Hunter’s 1922 All-Stars, none of the players had previously visited Japan. The world was more compartmentalized than today, and the visitors were surprised and astonished by the modernity of Tokyo, on course to becoming one of the world’s major cities. At the same time, there were obvious differences in food, language, and customs—it was both fascinating and disorienting.

Because Japan lacked professional baseball, the Americans would challenge college teams from the Tokyo Big Six University League—the highest level of baseball in the country—as well as all-star teams of alumni from those colleges and a few industry-sponsored squads.

Despite massive unemployment in Japan due to the collapse of the silk industry, 65,000 attended the opening contest; the ceremonial first pitch was thrown by Japanese Education Minister Tanaka, decked out in formal dress, including a top hat. The starting pitcher for Rikkyo University, Takeshi Tsuji, pitched well, allowing only four hits and four runs, all unearned, in six innings. Three of the unearned runs were due to missed fly balls by the Japanese right fielder, who did not wear sunglasses—according to Fred Lieb, it was considered cowardly to use them.

Al Simmons complimented Tsuji afterward for his deceptive sidearm delivery and impressive control, but the first game was an easy, 7-0, win for the All-Stars behind Bruce Cunningham, who allowed only two hits.20

The second game nearly resulted in a shocking Japanese victory. Masao Date, pitching for Waseda University, impressed Lieb, who afterward said that the Americans felt he would be a major league prospect if he were in the States. Date calmly escaped a first-inning bases-loaded jam by fooling Frankie Frisch on a full-count curveball, taken for strike three.21

The game was tied, 1-1, until the seventh, when Larry French surrendered a bases-loaded two-run double that gave Waseda a 3-1 lead. French, the possessor of an explosive temper, was removed from the game and furiously hurled his glove in disgust upon reaching the bench, cursing and screaming, “I’ve traveled nine thousand miles to be knocked out of the box by a bunch of Japanese college players!”22

Things did not get better. With only three pitchers along for the tour, others were utilized as emergency hurlers, including Lou Gehrig, who relieved French and allowed two more runs to score on a wild pitch and an out, stretching Waseda’s lead to four runs.23

Lieb, whom Landis had made responsible for the comportment of the players, watched in horror as French began hurling racial epithets from the bench. He attempted to shush the pitcher, pointing to Viscount Taketane Sohma, sitting at the end of the bench. Sohma, director of general offices at the Imperial Palace, had been educated in America and understood every word. To Lieb’s relief, he diplomatically chose not react to French’s tirade, which continued despite Lieb’s entreaties.24

The Americans ultimately stormed back to win, 8-5, saving French the embarrassment of losing, as Masao Date tired while Lefty Grove, who replaced Gehrig, struck out six straight batters on 19 pitches to end the game. Lieb later revealed that the All-Stars were arguing among themselves on the bench until Date walked the bases loaded and Lefty O’Doul promptly cleared them with a double to key a seven-run eighth inning.25

Grove took command of the third game, against Meiji University, although the Americans were finding it difficult to score at will against Japanese pitchers, putting the lie to the predictions of Japanese naval officers aboard the Tatsuta Maru that they would score at least 20 runs every game. Meiji University kept the game close; starting pitcher Kakusaburo Onitsuka retired the first eight American batters he faced, and another pitcher, Yutaka Yasogawa, took care of Al Simmons and Willie Kamm on pop ups with the bases loaded later in the game. Meanwhile, Lefty Grove struck out 11 in six innings of shutout ball and the AllStars won, 4-0.

The seventh game was a lopsided, 11-0, win over the same All-Stars behind Grove, who was so dominant that the outfielders sat down in the outfield during the ninth inning—an unfortunate flashback to showboating that plagued the 1922 tour. Grove allowed only three singles.26

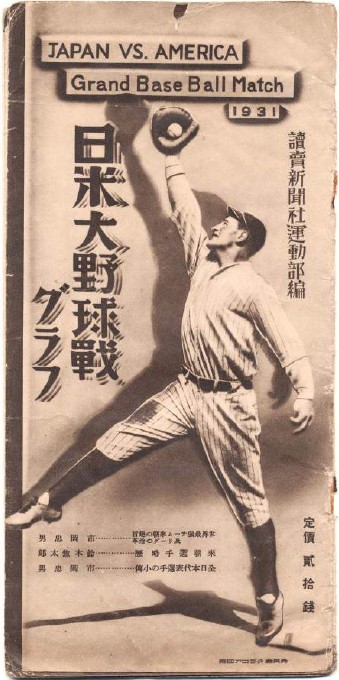

1931 All-American Tour Program (Rob Fitts Collection)

Despite the losses, the Japanese appetite for baseball seemed insatiable. Lou Gehrig noted that at every ballpark, thousands of those lacking a ticket remained outside, patiently waiting until after the game to catch a glimpse of the Americans. “The enthusiasm for baseball among the Japanese just about borders on the fanatical,” he explained. “At times it would take hours for our cars to take us from the park to the hotel.”27 Fred Lieb recounted seeing scores of locals occupying vacant lots before breakfast, playing baseball while wearing traditional wooden sandals.28

The American contingent traveled to Sendai, a city of 200,000 in the north of Japan nicknamed “The City of Trees.”29 The players were greeted at the train station at 7:00 A.M. by 10,000 people, virtually all of them frantically waving American flags, and then led to a waiting room equipped with 20 specially-upholstered chairs. There, three men in formal dress provided an official welcome to the city.30

The game in Sendai drew 15,000; Fred Lieb was told it was the largest crowd to ever gather in the city. While the players were taken by automobile to the ballpark, located atop a hill five miles from town, nearly half of those attending made their way on foot. There was a streetcar line, although the tracks ended some two miles from the ballpark. Despite the obstacles, fans were on hand three hours before game time, eager to soak in the experience.31

During the contest, easily won by the Americans, 13-2, Mickey Cochrane hit a home run that caromed off a flag-pole and struck a Japanese fan in the face. The injured man was escorted across the diamond to a restroom in the clubhouse, where he was treated for injuries to his mouth and sent on his way with 20 yen (the equivalent of about $10). A few minutes later, a doctor and nurse, thinking the man still in the bleachers, brought the game to a halt by tearing across the playing field, frantically looking for the injured party before receiving assurances that he had been safely removed.32

Between games, the players went sightseeing, played golf, and were treated as celebrities at official receptions and a seemingly endless string of parties. Rabbit Maranville celebrated his 40th birthday at the home of Taketane Sohma. A gong was struck 40 times to mark each year since the Rabbit’s birth, and the shortstop received a pair of ivory pigeons, a cake with a chocolate rabbit perched atop it, and a brand-new baseball glove signed by Japanese dignitaries and members of the All-Star team.

“Let somebody try to get that glove away from me,” declared Maranville. “I intend to have that glove shellacked as soon as I get home so that the signatures do not fade. Then I’ll see that it stays in the House of Maranville.”33

The Rabbit, whose physical dimensions were similar to those of the Japanese against whom he played, became a crowd favorite, especially when catching pop flies in his vest pocket, or in his lap while sitting on the infield. Japanese players attempted to imitate him, and fans doubled over with laughter as baseballs ricocheted off heads.34 Despite his deserved reputation for light hitting, Maranville even got into the act offensively, hitting two home runs in a one-sided victory against a team representing the Yawata Iron Works.35

At one point the Americans were hosted by Japanese Prime Minister Reijiro Wakatsuki. Unfortunately, when Wakatsuki was summoned from his office on urgent business, several of the players and their wives began filling their pockets with mementoes, including cigars, pens, and even small vases.36 Wakatsuki proved far beyond gracious in ignoring the obvious affront.

While all seemed relaxed and festive on the surface, the Americans remained blissfully unaware of the danger lurking in the country they were visiting. The same day the All-Stars defeated Keio University, a mass meeting was held in Tokyo to condemn the League of Nations for its condemnation of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. In defiance, Japan sent additional troops to assist in a tense standoff outside Tahsing, which they had occupied.37

Meanwhile, the All-Star roster, numbering only 14 to begin with, was depleted during the middle of the tour, with both Lou Gehrig and Lefty O’Doul sidelined by injury.

Gehrig was hit by a pitch, suffering painful bone bruises to several fingers. During the tour’s seventh game, O’Doul suffered broken ribs in a collision with Japanese infielder Osamu Mihara.

O’Doul’s injury resulted from an incident ignited by name-calling on the part of the All-Stars. Upset by Gehrig’s injury, the Americans began insulting the Japanese, who for the most part took it in stride, with the exception of Mihara, who began returning the insults.

O’Doul declared that he would teach Mihara a lesson, and bunted to the right side of the infield in his next at bat. As planned, Mihara fielded the ball and rushed over to tag O’Doul. But Mihara recognized O’Doul’s intentions and was ready, meeting the American full force and sending him to the ground, clutching his ribs. O’Doul was out for the final 10 games. Worse, he was unable to golf.38

After being sidelined, O’Doul instructed Japanese players and visited with old friend Sotaro Suzuki, whom he had met in New York in 1928, when Suzuki was working in the States for a silk firm and O’Doul was playing for the Giants. Suzuki, now employed by Matsutaro Shoriki at his newspaper, especially enjoyed sitting in the hotel lobby in Yokohama with its spectacular views of the harbor, talking baseball with O’Doul and the other American stars.39 And with time on his hands, O’Doul made an effort to educate himself about Japan and its culture.

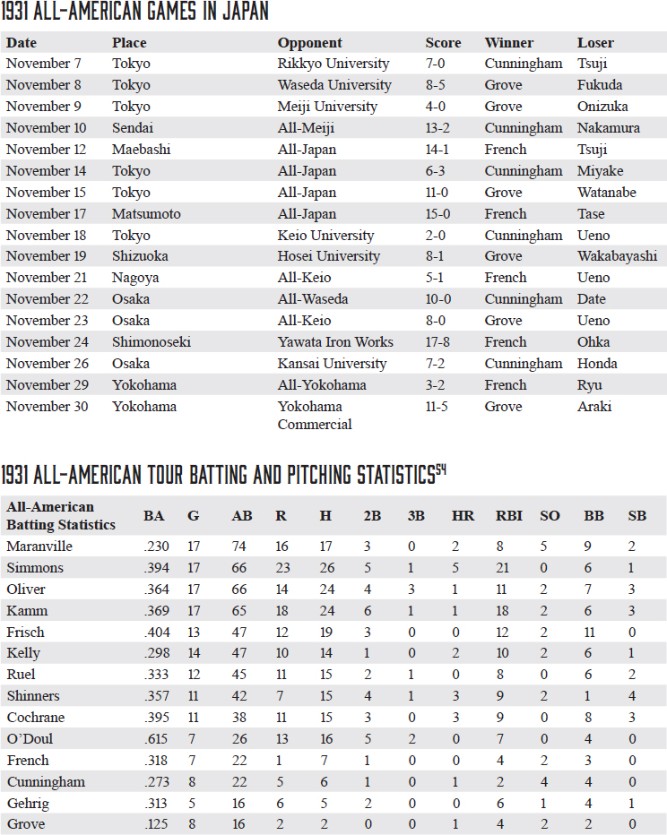

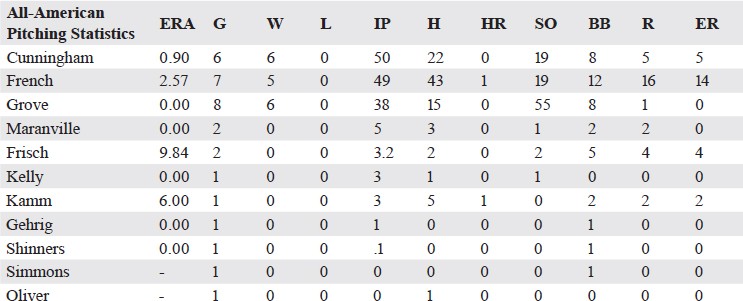

Despite his abbreviated performance, Lefty O’Doul boasted the highest batting average on the tour at .615, including five doubles and two triples. Frankie Frisch was second at .404.40 Al Simmons led the team with five home runs. As a team the All-Stars batted .346, scoring 149 runs while allowing only 30.

Bruce Cunningham and Larry French pitched well, but Lefty Grove was especially dominating; he did not allow an earned run during the entire trip and struck out 55 batters in 38 innings. In Yokohama, he emptied the outfield prior to the last out, and then instructed Maranville and Frisch to turn their backs to the plate before striking out the final hitter on three pitches to end the game.41

After their 17th contest, against Yokohama Commercial High School, the Americans sailed back to the States.

Herb Hunter and Fred Lieb insisted that the Japanese would eventually match the Americans in caliber of play, with Lieb declaring their outfield defense already major-league quality.42 “Outfielders on the teams the All-Stars played could go back just as far, come in as fast and cover just as much ground as any outfielder in either major league,” he said.43 Mickey Cochrane added, “…to get a ball over their head, you practically have to hit it out of the park, for they crash into the fences as though they were made of rubber.”44

In addition to Masao Date, another pitcher who impressed the Americans was a diminutive left-hander from Keio University, Seizo Ueno. He tossed a complete game in a tough, 2-0 loss, allowing only six hits and one earned run; Bruce Cunningham defeated him with a one-hitter. Ueno pitched three innings of hitless relief in another game.45

When the players landed in San Francisco, Mickey Cochrane reported, “I didn’t know a country could be so baseball-crazy as Japan is. I know I signed so many shoes I could not count them; papers, hats, shirts, gloves, in fact, everything they could find. It was a wonderful trip, but, believe me, your skyline this morning was the prettiest sight I have seen since we left.”46

Catcher Muddy Ruel—a practicing attorney in the off-season and the first ballplayer ever admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court—felt the game was held back by the lack of a middle class in Japan and thought it a shame that the country lacked professional baseball. As an example, he pointed to a player he had befriended, third baseman Shigeru Mizuhara. “I asked Muzi [sic] what he was going to do after he finished college,” said Ruel, “and he informed me that he was delighted to be able to say he had lined up a job as a driver of a street car. Imagine that—and he is the best third baseman in Japan.”47

Al Simmons was puzzled that the Japanese were excellent on defense, but impotent with the bat. “The Japanese lads,” said Simmons, “of course, are physically small compared to us, but that fact should not prevent them from being good hitters. For we have many fine hitters among the small men in the big leagues.”48

Herb Hunter praised the Japanese, noted no obvious tensions about Manchuria, and announced that when conditions improved, he would start an eight-team Japanese major league, backed with $6,000,000 from Japanese businessmen.49

But conditions did not improve, either for Hunter or for US-Japan relations. Prime Minister Wakatsuki’s government resigned while the Americans were returning home, in large part due to its inability to control the Japanese military. That task fell to his successor, Tsuyoshi Inukai, who had publicly supported the invasion of Manchuria. In January 1932, three Japanese soldiers pulled American consul Culver Chamberlain from his automobile and punched him in the face several times, bringing rebuke from the United States government and demand for apologies and arrests.50 Four days later a Korean activist made an attempt on the life of Emperor Hirohito, at which point Inukai and his government offered its resignation, but Hirohito refused to accept it.51

Four months later, Inukai was assassinated inside his residence by ll junior officers.52

Herb Hunter returned to Red Bank, New Jersey, basking in what he considered his greatest success, much to the chagrin of Matsutaro Shoriki. The Japanese newspaper publisher was angry that—despite gate receipts that had far exceeded expectations— Hunter intended to hold on to all of the extra money, leaving Shoriki in debt even as he had taken on sponsorship of the entire tour. Hunter, who for some reason ended up handling tour funds despite an order from Landis not to, reluctantly surrendered a slightly larger cut, but Shoriki still suffered a significant financial loss underwriting an obviously a successful venture.53 He would not forget this.

Hunter returned to Japan in 1932 on a coaching tour with Lefty O’Doul, Ted Lyons, and Moe Berg, but he did not lead any more all-star teams to the country or have anything to do with establishing professional baseball there, largely due to the same weaknesses of which Landis had been wary, and that Matsutaro Shoriki had experienced to his own detriment. In the summer of 1934, Hunter took a team from Harvard University to Japan. But four months later, when the most important major-league tour of them all was staged, Herb Hunter was left out in the cold in favor of an effort spearheaded by Lefty O’Doul that featured, finally, the long-awaited appearance of Babe Ruth in Japan.

DENNIS SNELLING is a three-time Casey Award finalist for Best Baseball Book of the Year, including for The Greatest Minor League: A History of the Pacific Coast League, and Lefty O’Doul: Baseball’s Forgotten Ambassador, which was runner-up for the award in 2017. He was a 2015 Seymour Medal finalist for Johnny Evers: A Baseball Life. Snelling is an active member of the Dusty Baker and Lefty O’Doul SABR chapters in Northern California. He lives in Rocklin, California.

NOTES

1 “Haoles Team to Hold First Big Meeting Tuesday,” Honolulu Advertiser, February 5, 1921: Section 2, 4.

2 “Herb Hunter Is Not Worrying,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 6, 1922: 14; “Japan’s Ball Fans Look to Cards to Win,” Honolulu Advertiser, May 17, 1922: 4.

3 Ed R. Hughes, “Baseball Invasion of the Orient Breaks Up in Big Blow-Off at Kobe, Japan,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 28, 1921: 7.

4 “Herb Hunter in S.F. from Japan,” San Francisco Examiner, February 27, 1931: 21, 22. This is the most famous of the stories about Herb Hunter and was repeated innumerable times in various incarnations over the years.

5 Ed R. Hughes, “First No-Hit Game of Year Defeats Seals,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 26, 1919: 8.

6 Ed R. Hughes, “Los Angeles Takes Seaton to Help Staff,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 24, 1918: 10.

7 AI C. Joy, “Herb Hunter Steals Home in Seventh and Wins Game for Seals,” San Francisco Examiner, October 11, 1917: 21.

8 Fred Lieb, Baseball as I Have Known It (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Inc., 1977), 198.

9 Robert K Fitts, Banzai Babe Ruth (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 16; William Peet, “Hunter Banking on The Bambino,” Honolulu Advertiser, February 20, 1931: 10.

10 Fitts, 18.

11 “Herb Hunter to Manage R.B. Towners the Coming Season,” Red Bank (New Jersey) Standard, March 13, 1931: 7.

12 A rule was adopted that allowed only three of the four World Series players to appear in the same game. Frederick G. Lieb, “More Baseball Now Being Played by Japanese Youths Than by Youngsters of the United States, Asserts Fred Lieb,” The Sporting News, January 7, 1932: 7.

13 “Brubaker Clan Beats Gehrigs,” Oakland Tribune, October 12, 1931: 19, 20; Ed R. Hughes, “Seals Defeat Major League Stars, 5-3,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 13, 1931: 21, 23; “Major League Stars Defeat Seals, 13-6,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 15, 1931: 25; “Major League Stars Lose to Home Team; Grove Pitches,” Sacramento Bee, October 15, 1931.

14 “Seals Bombard Lefty Grove to Beat Big Leaguers, 7-4,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 14, 1931: 27.

15 Bob Roberts, “Pilot Fees to Be Cut; Oaks Home from L.A.” San Francisco Chronicle, October 15, 1931: 16.

16 Don Watson, “Record Crowd Sees Major Leaguers Win, 10-0,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 21, 1931: 11.

17 William Peet, “Grove Likes Hawaii and May Live Here,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 22, 1931: 10.

18 Frederick G. Lieb, “Japs Greet Touring Major League Stars,” The Sporting News, December 3, 1931: 7.

19 Lieb, “Japs Greet Touring Major League Stars.”

20 “Tokio Nines Play Well,” Japanese American News, December 2, 1931: 8.

21 Frederick G. Lieb, “Touring the Orient,” The Sporting News, December 10, 1931: 4.

22 William Peet, “Sport Flashes,” Honolulu Advertiser, December 14, 1931: 10.

23 Frederick G. Lieb, “More Baseball Now Being Played by Japanese Youths Than by Youngsters of the United States, Asserts Fred Lieb.”

24 Lieb, Baseball as I Have Known It, 203; “Touring the Orient,” The Sporting News, December 24, 1931: 4.

25 Peet, “Sport Flashes;” Abe Kemp, “Major Stars Return from Japanese Trip,” San Francisco Examiner, December 19, 1931: 18; Lieb, “More Baseball Now Being Played by Japanese Youths Than by Youngsters of the United States, Asserts Fred Lieb.”

26 “Major Leaguers Score Sixth Win,” Nippu Jiji, November 16, 1931: 3.

27 “Baseball in Japan Amazes Lou Gehrig,” Boston Globe. December 23, 1931: 11.

28 Peet, “Sport Flashes.”

29 In 2011, Sendai was struck by an earthquake and tsunami that destroyed the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

30 Lieb, “Touring the Orient,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1931: 4.

31 Lieb, “Touring the Orient,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1931: 4; Dennis Snelling, Lefty O’Doul: Baseball’s Forgotten Ambassador (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 95.

32 Lieb, “Touring the Orient,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1931: 4.

33 Frederick G. Lieb, “Touring the Orient,” The Sporting News, December 24, 1931: 4.

34 “Interest in Japan Amazing to Gehrig,” New York Times, December 23, 1931.

35 Lieb, “More Baseball Now Being Played by Japanese Youths Than by Youngsters of the United States, Asserts Fred Lieb.”

36 Lieb, Baseball as I Have Known It, 204; The Sporting News, January 7, 1932: 7.

37 International News Service, “Compromise on Manchurian Row May Be Offered,” Nippu Jiji, November 14, 1931: 1.

38 Lieb, Baseball as I Have Known It, 205.

39 Letter, Sotaro Suzuki to Lefty O’Doul, February 5, 1932.

40 Frederick G. Lieb, “O’Doul Best with Bat on Japanese Tour,” The Sporting News, January 14, 1932: 7; Pfc. Howard Bryan, “The Babe in Japan,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, April 25, 1948: 9.

41 Abe Kemp, “Major Stars Return from Japanese Trip,” San Francisco Examiner, December 19, 1931: 18.

42 Don Watson, “Solem Strong on Condition,” Honolulu Star Bulletin, December 14, 1931: 10.

43 Peet, “Sport Flashes.”

44 Kemp.

45 Lieb, “More Baseball Now Being Played by Japanese Youths Than by Youngsters of the United States, Asserts Fred Lieb.”

46 Kemp.

47 James M. Gould, “Baseball Now Japan’s National Game, Says ‘Muddy’ Ruel, Back from Tour,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 29, 1931: 4B. Mizuhara, who was eventually inducted into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame, was held as a prisoner during and after World War II by the Russians until Cappy Harada secured his release, which was celebrated during an emotional pre-game ceremony at which Mizuhara declared, “I, Mizuhara, have finally come home.” (See Sayuri Guthrie-Shimizu, Transpacific Field of Dreams, Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2012, 249.)

48 “Tokio Nines Play Well,” Japanese American News, December 2, 1931: 8.

49 Sidney Wain, “Hunter, Back at Fair Haven, Tells of Baseball Experiences in Japan,” Long Branch (New Jersey) Daily Record, December 30, 1931: 8. Hunter had earlier written to his brother in Melrose, Massachusetts that he planned to remain behind to start a professional league in Japan in 1932. (“Crowds Watching U.S. Team Play,” Boston Globe, December 18, 1931: 32.)

50 Constantine Brown, “Stimson Prepares to Act in Attack on U.S. Consul,” Washington Evening Star, January 4, 1932: 1

51 Associated Press, “Hirohito Escapes Injury in Bomb Attack in Tokio,” Washington Evening Star, January 8, 1932: 1.

52 Hugh Byas, “Army to Stop Agitation,” New York Times, May 16, 1932: 1. Fortunately, film star Charlie Chaplin, a guest of Inukai, was away from the residence at the time of the attack, attending a sumo match.

53 Fitts, 21.

54 Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs, U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 85.