Before the Babe: Gavy Cravath’s Home Run Dominance

This article was written by Bill Swank

This article was published in 2000 Baseball Research Journal

Most baseball fans know that Roger Maris, Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, and Henry Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s season and career home run records. But even the experts disagree on whose season and career home run records the Babe broke. Perhaps there is apathy because among the early home run hitter were flukes, fakes, and mostly forgotten or forgettable ballplayers.

During the National League’s inaugural season of 1876, a total of 40 home runs were entered on the record books. The following year, that figure dropped to only 24 home runs for the entire league. This was an era of inside-the-park home runs. Hall of Famer Buck Ewing of the original New York Giants became the first player to reach double digits with ten circuit blows in 1883. That same season, another reputable hitter, Harry Stovey, playing for the Louisville Colonels in the rival American Association, slugged 14 round-trippers.

Then, suddenly, Ned Williamson blasted 27 home runs for the Chicago White Stockings in 1884. The previous year he had hit a pair of four-baggers and the following season, he would hit but three home runs. His record is tainted because before this record performance, balls hit over the 196-foot-distant right field fence at Chicago’s Lake Front Park were ground rule doubles. The following year in their new West Side Park (also called the Congress Street Grounds) balls hit 216 feet over the fence were also called doubles. A major change in the game occurred in 1893 when the pitcher’s position was moved from fifty feet to the present distance of 60 feet, 6 inches. But home run hitting did not increase perceptibly at the greater distance. It was not until 1899 that the highest “legitimate” home run total (25) for the nineteenth century was achieved by Washington’s Buck Freeman.

Stovey became the first player to reach 100 career home runs. He finished with 120,121, or 122 homers depending on the source. This figure was exceeded by Hall of Famer Roger Connor who, again depending on your source, hit between 132 and 138 home runs from 1880 through 1897.

When Ruth came along he changed everything, of course. But when the Babe first began thinking about hitting home runs in 1918, one man was already setting home run records which some experts thought could never be duplicated. Remarkably, Clifford “Gavy” Cravath was thirty-one years old when the Philadelphia Phillies acquired the powerful outfielder from the Minneapolis Millers in 1912. The preceding year, he had hit 29 home runs to lead the American Association. This was the highest season total that had yet been achieved in Organized Baseball during the twentieth century. (Cravath’s nickname is a source of confusion. Although he signed it “Gavy,” it is pronounced to rhyme with “savvy.” Sportwriters of the time added the extra “v.” I spell it here as he did.)

Four years earlier Cravath had been unable to break into the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame outfield dominated by Tris Speaker and Harry Hooper. When granted a second chance in the major leagues, he led or tied for the National League lead in home runs six times between 1913 and 1919. This feat alone was unprecedented in baseball history. With one more home run, his string would have covered seven consecutive years.

Cravath hammered 24 home runs during his signal season of 1915 when he and Grover Cleveland Alexander carried the lowly Phillies to their first ever World Series appearance. After Cravath drove in the deciding run in the Series opener against the Red Sox, Philadelphia lost each of the next four games by a single run. Ironically, out of respect for Cravath’s righthanded power, Boston did not use in the Series a very promising young lefthander with a 18-8 record during the regular season. His name: Babe Ruth.

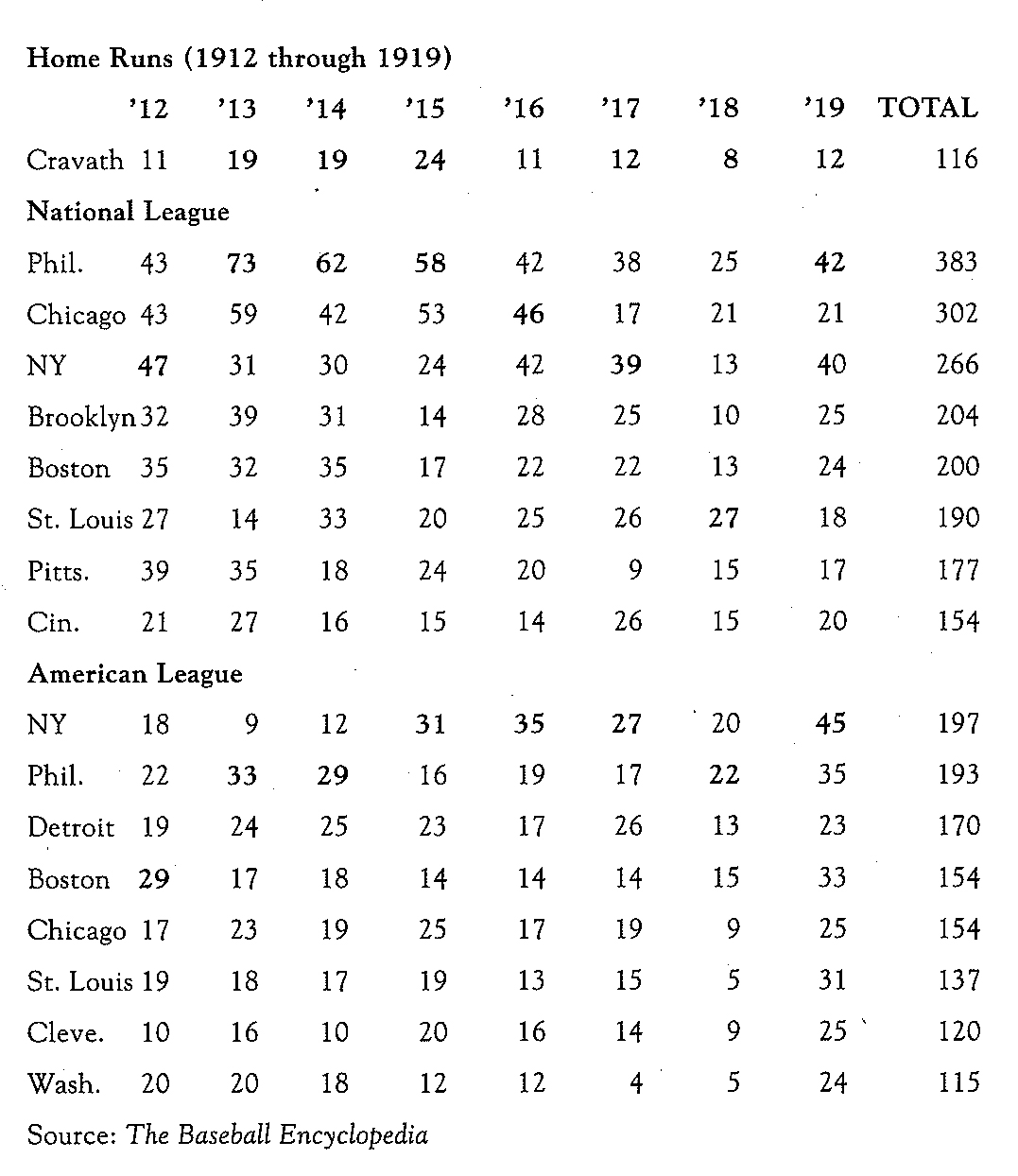

That season Cravath had as many or more home runs individually than twelve of the sixteen major league teams hit collectively. He produced more than 10 percent of all the home runs hit in the National League that year. At the time, these 24 home runs were acknowledged as the “modern” home run record.

Twice, in 1913 and 1915, Cravath led the National League in RBIs (128 and 115 respectively). His home run and RBI percentages were the highest of the Deadball Era. A ten-year career .287 hitter, he was the most feared slugger of his time.

| Player | HR% | Player | RBI% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gavy Cravath | 3.01% | Gavy Cravath | 18.1% | |

| Tilly Walker | 2.33% | Ty Cobb | 17.4% | |

| Buck Freeman | 1.95% | Frank Baker | 16.7% | |

| Mike Tiernan | 1.78% | Sam Crawford | 16.7% | |

| Fred Luderus | 1.73% | Sherwood Magee | 16.2% | |

| Frank Baker | 1.60% | Honus Wagner | 15.1% | |

| Hugh Duffy | 1.49% | Heinie Zimmerman | 15.1% | |

| Charlie Hickman | 1.48% | Joe Jackson | 15.1% | |

| Zach Wheat | 1.45% | Duffy Lewis | 14.7% | |

| Jimmy Ryan | 1.45% | Tris Speaker | 14.0% |

Over the course of his eleven years in the big leagues, Gavy accumulated 119 career home runs. From 1912 through 1919, Cravath hit more home runs (116) than the entire Washington Senators team (115) hit during the same period.

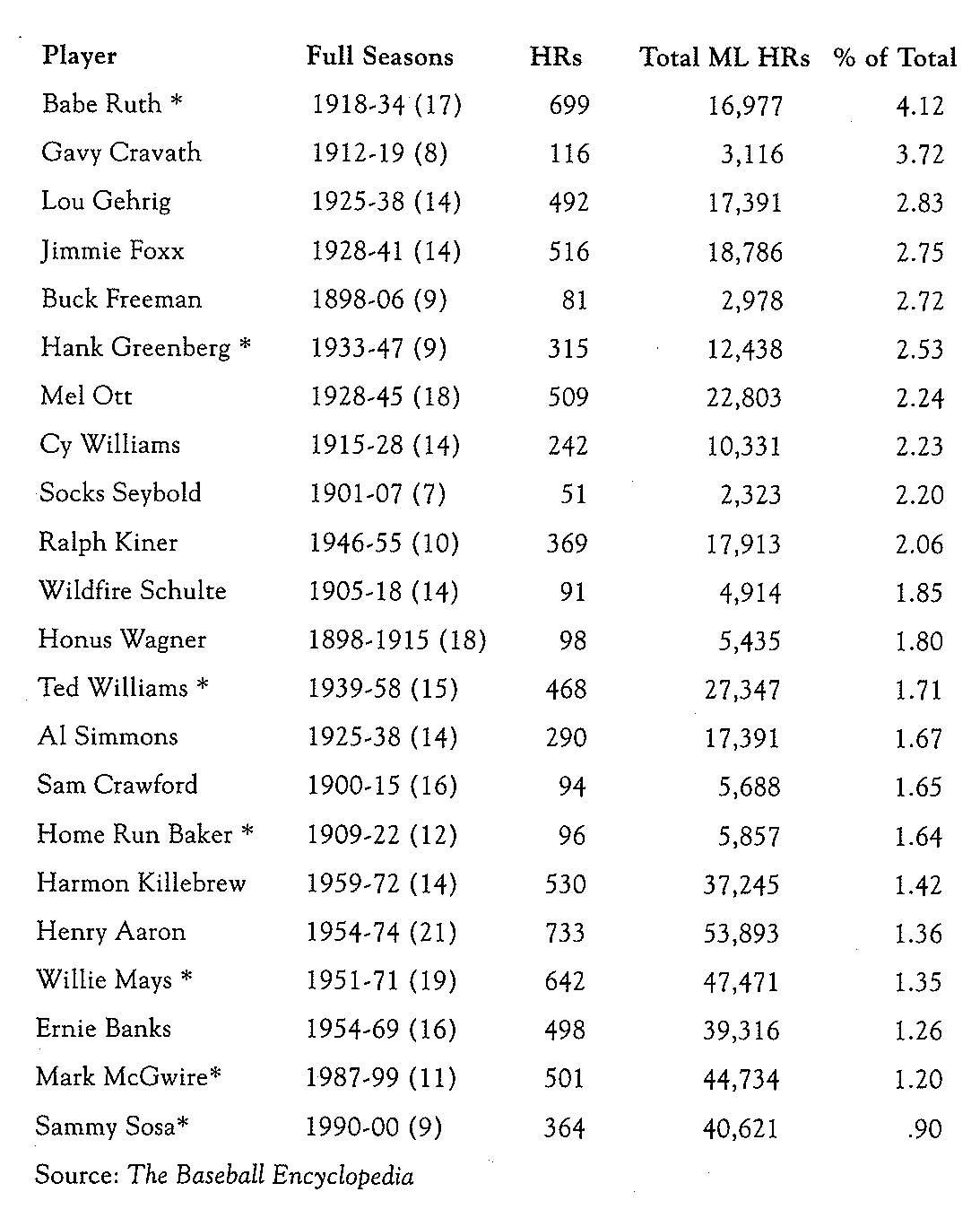

It is tough to evaluate players from different eras. The purpose of the following chart is to show the impact of the power hitters on their own eras and their relationship to one another. As outstanding as the individual numbers posted by Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa during the past few baseball seasons, with the current emphasis on the power game, their percentage of the total home runs hit by contemporaries during similar productive years is relatively low.

Not surprisingly, Babe Ruth was and remains the most dominant home run hitter of his or any era. Significantly, Gavy Cravath places a strong second on this impressive list of sluggers. The asterisk marks players for whom I eliminated seasons interrupted by military service, injuries, salary disputes, etc. I also eliminated some rookie partial seasons.

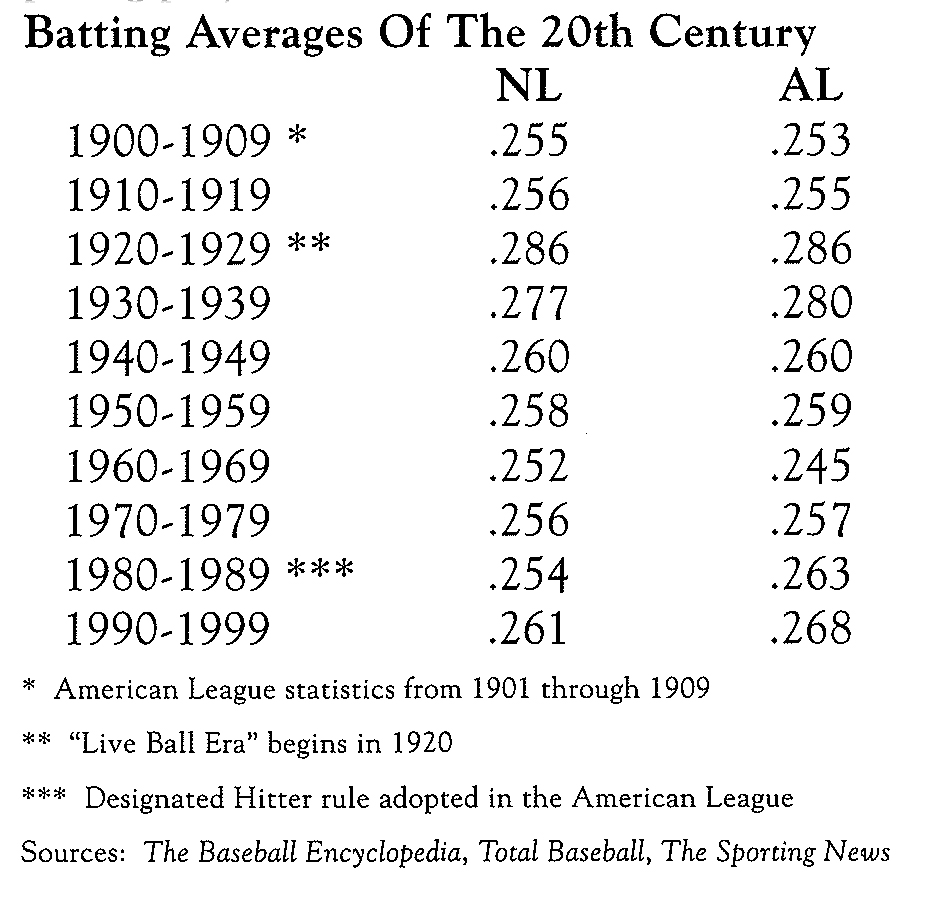

The following chart shows how all batters benefited during the “Live Ball Era.” The entire National League, including pitchers, hit for a .303 average in 1930. Cravath’s .287 lifetime batting average would have been only average for the 1920s, but he was almost thirty percentage points above the major league average during the ‘teens. We recall the legendary hitters of the 1920s and 1930s, but forget that everyday players were also putting up impressive numbers. This is yet another example of the difficulty in comparing players from different eras.

Ruth broke Cravath’s modern season record with his 25th home run on Labor Day of 1919. The Babe hit his 120th home run off Jim Bagby of Cleveland on June 20, 1921, to break Gavy’s career record.

At cozy Baker Bowl, the Phillies home ballpark, it was only 280 feet down the line to the infamous forty-foot high right field wall. Cravath was a right-handed batter who had taught himself to go to right field to take advantage of a similar 279 foot foul line and thirty-foot fence at Nicollet Park in Minneapolis. While he was a Miller, manager Joe Cantillon threatened to fine him $50 if he hit any more homers over the right field barrier. Apparently Cravath had broken the same window of a Nicollet Avenue haberdashery three times during a single week.

Although the right side was not his power field, 92 of Gavy’s home runs were hit in Baker Bowl. His play in Philadelphia with its inviting right field porch has often been used as an argument against Cravath’s election into Baseball’s Hall of Fame.

With each passing year, the accomplishments of Gavy Cravath and other pre-1920 players continue to fade. In 1994, the Hall of Fame’s Veterans Committee was given the opportunity to select one individual a year from the nineteenth century for enshrinement in Cooperstown. It has chosen two managers (Ned Hanlon and Frank Selee) , but only three players (Vic Willis, George Davis, and Bid McPhee). No selection was made in 1997. Perhaps, someday, a similar window will open for Deadball players.

Until then, goodbye to the other early home run kings like Dandy Wood, Braggo Roth and Old True Blue Richardson. Where have you gone, Abner Dalrymple?

BILL SWANK is the author of Echoes from Lane Field: A History of the San Diego Padres, 1936-1957. A crusader for old ballplayers, he has campaigned for years to get San Diego’s first major leaguer, Gavy Cravath, elected to the Hall of Fame.