The Fifties: Fire Away!

This article was written by Paul L. Wysard

This article was published in 2000 Baseball Research Journal

Baseball’s 1950s are remembered by different people in different ways: stagnant, brilliant, racist, progressive — it all depends on the perspective of the fan. But one thing is certain and incontrovertible: baseball during the ’50s became a contest of raw power.

Sixteen players have hit 500 or more career home runs. Seven of them played at least five full seasons in the ’50s. An eighth man hit his first 73, and a ninth his first 25.

Of the twenty-six sluggers with seventeen or fewer at-bats per home run, seven (27 percent) logged at least six full campaigns in the ’50s. Three more were active for one to four years.

The 1948 and 1949 seasons were harbingers of the coming explosion. Scoring numbers began to rise after the immediate postwar years. Five teams drove in more than 800 runs. Three players exceeded 150. None of those marks had been reached in the previous eight seasons.

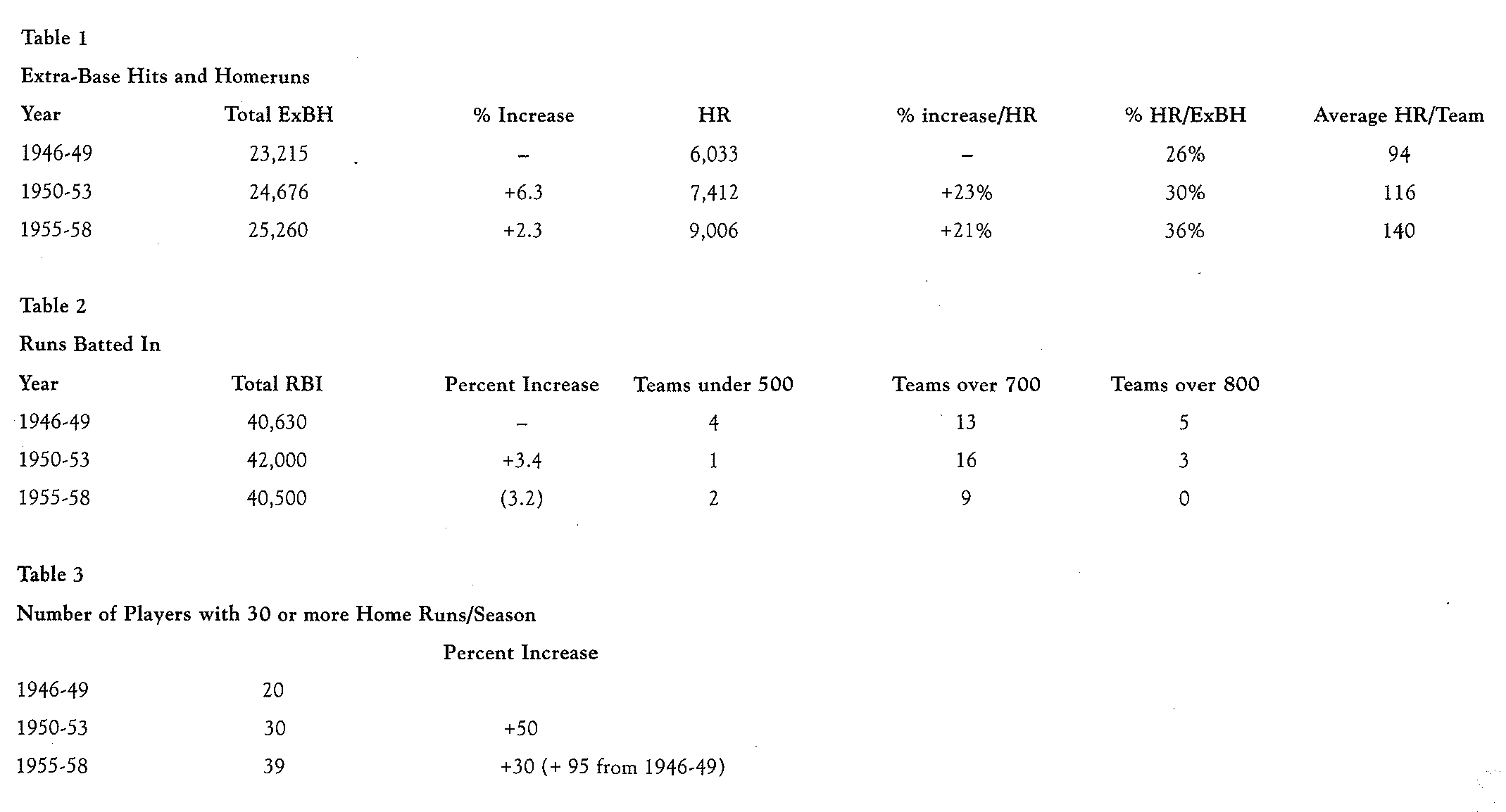

It was the 1950 Boston Red Sox, though, with over 1,000 runs scored and almost 1,000 driven in, who set the power table at which almost all teams would dine for the next ten years. The three tables below illustrate the surge.

(Click image to enlarge)

There had been quantum leaps in offense earlier, most notably in 1930-32, when extra-base hits increased 8 percent, home runs 18 percent, and the home run percent of extra-base hits from 20 percent to 23 percent, but thereafter the homer growth rate was more moderate. Over the next ten years, through 1941, it was 10 percent.

After the initial leaps in the categories as the ’50s began, performance — except in home runs — leveled off. The number of teams with 120 or more home runs in 1946-47 was four; in 1950-51, all sixteen reached that level. By 1953-54 total output rose to over 4,000 in the two-year period, the highest ever.

In 1946-49 one team hit more than 200 home runs in a season — the ’47 Giants of Mize, Cooper, and company, with a record 221. Those Giants were also the only team to surpass 180 in that period. From 1950-60 fourteen teams finished a season with more than 180, three of which were over 200 and one of which (the ’57 Braves) came up one shy at 199. The ’56 Reds tied the ’47 Giants record.

At the same time, “speed” numbers declined. Players went “station to station,” waiting for the big hit. Managers and coaches took off the running signs. There were 1,587 triples in 1946-47. By 1957-58 there were only 1,320, a 16 percent decrease in a decade and a direct contrast to the 60 percent rise in homers over the same span. The Buddy Lewises, Phil Cavarettas, Dale Mitchells, Bob Dillingers, and Harry Walkers were phased out in favor of slow-moving sluggers like Hank Sauer, Gus Zernial, Ted Kluszewski, Joe Adcock, and Roy Sievers. Eventually, we began to see all those Hall of Famers in the 500 club: Mays, Mathews, Mantle, Aaron, Banks, and Frank Robinson. At the same time, Ted Williams, Ralph Kiner, and Johnny Mize continued their long power patterns, and Musial was … well, Musial. But even he caught the long-ball fever: in his first seven years, in the ’40s, he averaged 20 homers per season. In his first seven years in the ’50s, his annual output rose to 30.

Base stealing also became less of a priority. In 1946- 47, over 1,600 sacks were swiped. By 1953-54, steals had dropped to 1,363 (-15 percent). Just as we see so many from that decade high on the home run list, so also do we see few names in the speed categories. Of those who have hit 150 or more triples, only two, Musial and Clemente, played at all in the 1950s. Of the roughly three dozen players with more than 400 career stolen bases, only one, Luis Aparicio, was a ’50s performer.

Even the mobile Dodgers put on the brakes. The Brooklyn pennant winners in 1947 and 1949 averaged 48 triples and 102 steals. The 1956 titleists hit 36 triples and stole 65 bases. Home runs? A jump from 117 to 180.

The only team to buck the power trend successfully was Chicago — the memorable “Go-Go” White Sox. Throughout the decade, they finished second or third in the American League, and finally made it to the top in 1959, becoming the only pennant-winning team of the ’50s with more than 100 stolen bases. They were also the first club in eleven seasons to win a title with fewer than 100 homers and the first team in twenty-five seasons to be a champion with fewer than 100 homers and more than 100 stolen bases.

No position better illustrates the shift than that of catcher. In 1946-47 backstops hit 170 homers (Walker Cooper and Ernie Lombardi hit a third of them). In 1957-58, men behind the plate more than tripled their output to 520. Certainly, new spark plugs Berra and Campanella were big factors, but don’t forget Lollar, Seminick, Crandall, Westrum, Lopata, Sammy White, and, a bit later, Bailey and Triandos. The typical catcher in 1946-47 — scrappy defense, .240-.250, five homers, 40-45 RBIs — didn’t have a job seven or eight years later.

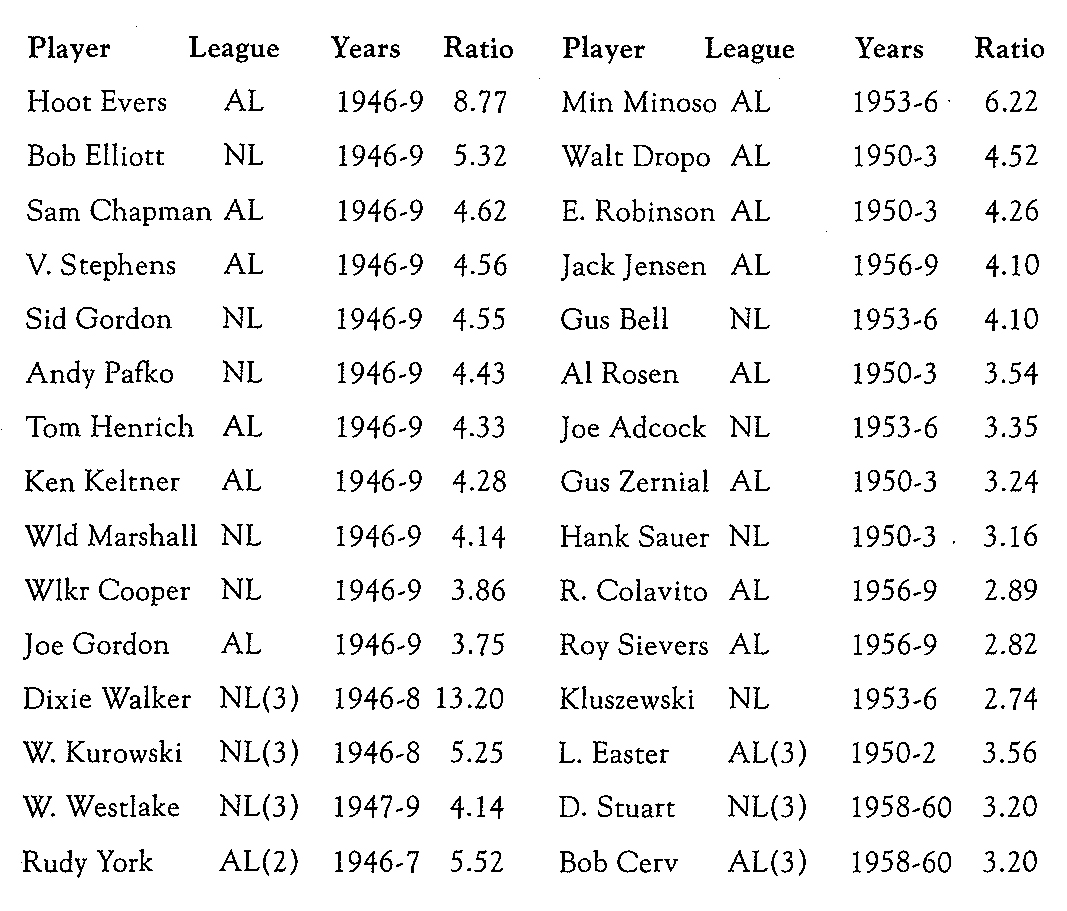

SABR colleagues will not find much support in this corner for overuse of the Home Run/RBI Ratio. It is a suspect statistic in many ways, but it does provide some confirmation of the ’50s style. In an attempt at levity in the midst of the Cold War nuclear arms race, wags in Congress and elsewhere talked about achieving a “Bigger Bang for a Buck.” How did that apply to baseball? Below is a list of the HR/RBI ratios of the important, but non-Hall of Fame, 100-RBI men. Aside from the familiar Hall of Famers, there weren’t any more 100-RBI people in 1946-49 except for four who logged a lot of service before and after 1950 — Gil Hodges, Bobby Thomson, Carl Furillo, and Del Ennis — all fine run producers who exhibited the traits of both periods.

Like Evers and batting champions Dixie Walker and Mickey Vernon, the exciting Minnie Miñoso was the kind of slash hitter who could drive in 100 runs with less than 20 homers. He was an oddity in his time.

The ’50s gave us many more bombers, including Wally Post (3.0 ratio), Larry Doby (3.55), Jim Lemon (3.2), Vic Wertz (3.7), Frank Thomas (3.2), and Roger Maris (3.25). Finally, there was Dale Long (3.23). He never drove in 100 runs, but he set a record with eight home runs in eight consecutive games in 1956.

Not mentioned yet is the player who hit the most long balls in those days: Duke Snider, with 326 homers from 1950 through 1959, including five consecutive seasons at 40 or more. The man with the highest annual output over the most years was fellow Hall-of-Famer Mathews, who averaged 37 from 1952 through 1959, with four 40+ campaigns. Their ratios, however, match the ’50s pattern, with Snider a little over, and Mathews slightly under, 3.0.

When Ted Williams hit his 521st home run in his last at-bat in 1960, the shot not only capped his career, but also closed out ’50s-style baseball. The Yankees, in the next (Maris) year, hit it out 240 times, but expansion muddied comparisons. And the ’60s soon turned to speed and defense, highlighted by the Dodger teams of the ’60s, and the ’68 season in which Bob Gibson, Denny McLain, and others held all teams under 700 RBIs.

Was ’50s big-bang baseball a reflection of the society and the politics of the day? Almost every aspect of life was tied to power and size: Incredibly devastating bombs, hordes of people in military service, expanding corporations, huge automobiles, a vast highway system, increasingly potent aircraft, booming urban areas, and some sense of endless progress. Speculation can be shredded; supposition is safer. And so let us suppose that, yes, there was a connection.

Sometime soon, someone will analyze the “Home Run Derby” that was baseball in the ’90s — not only the McGwire-Sosa races and the big 70, but also the growing number of folks who went deep 45, 50 times. It was the greatest long-ball era ever, but it had a pure and hardy ancestor over forty years before when the motto was: “Fire Away!”

PAUL L. WYSARD is a life-long resident of Hawaii who first saw major leaguers play in military service during World War II. A retired private school administrator, he was also a contributor at the 1998 SABR Convention.