Examining Dusty Baker’s Hope: Is Help on the Way?

This article was written by David C. Ogden

This article was published in Fall 2023 Baseball Research Journal

Had Michael Brantley stayed healthy, the 2022 World Series could have avoided becoming the first Fall Classic since 1950 to have no African American players. As it was, the Astros outfielder and lone African American on either team’s roster suffered a season-ending shoulder injury that kept him out of postseason play.1 The only other African American in the dugout was Astros manager Dusty Baker, who gave a dour assessment on the absence of African American players: “[It] looks bad … I am ashamed of the game,” he said. “It lets us know there’s obviously a lot of work to be done to create opportunities for Black kids to pursue their dream at the highest level.”2

But Baker also offered optimism. He forecast brighter days ahead for African Americans in baseball: “The [baseball] academies are producing players. … [T]here is help on the way. You can tell by the number of African-American No. 1 draft choices.”3

Baker’s comments refer to two measures of success in increasing the proportion of African Americans in the minor leagues and Major League Baseball: the number of African Americans in the most competitive levels of youth travel baseball and in the MLB amateur draft. The 2022 draft, in which four of the first five selections were African American, gave credence to his prediction that “help is on the way.” So do the almost 19 percent of first- and second-round picks who are African American from the last 10 drafts.4 With systemically low numbers of African Americans at every level of baseball, those percentages and Baker’s comments merit further exploration into the draft and the extent to which youth baseball organizations are helping Black players to get drafted (or be recruited by a college). The following research questions will drive this exploration:

- RQ 1: How many African Americans are being selected in the first five rounds of the draft?

- RQ 2: To what extent are African Americans, in proportion to other races, coming down the talent pipeline (beginning with youth travel ball)?

- RQ 3: Through what types of youth baseball programs are African Americans entering college baseball and/or the draft?

Baker’s comments imply that youth travel baseball will boost the percentage of players who are African American in the MLB amateur draft. By examining MLB draftees’ playing histories, we can clarify the link between youth travel baseball and higher leagues—both college and professional ball. Their histories reveal the types of baseball “academies” from which African American draftees come and whether there are racial differences in the number of draftees “graduating” from those “academies”—a moniker that many youth travel teams began applying to themselves in the 2000s.5

To put Baker’s comments in perspective requires understanding the changes in youth travel baseball over the past two decades. Looking at the number of African Americans who have played for such academies and who were subsequently drafted by a major league team can be used to test Baker’s assertion. Do these academies serve as portals for African Americans?

THE TRANSFORMATION OF ELITE YOUTH BASEBALL

In his 2009 book, Perfect Game USA and the Future of Baseball: How the Remaking of Youth Scouting Affects the National Pastime, Les Edgerton argued that travel team baseball was superseding high school baseball as a more auspicious path to college and professional baseball.6 Travel ball has encroached on the two mainstays of high-level competitive baseball for mid- and late-teen males: high school baseball and American Legion Baseball.

Over the past few years, both state high school associations and American Legion chapters reported fewer male teens playing baseball. The number of North Carolina high school players dropped by more than 500 between 2016 and 2022, and a 2019 national survey also showed a decrease in high school baseball players, along with other scholastic sports.7 Even the Huffington Post sounded the alarm that “high schools are struggling to recruit enough players.”8 Although part of the decrease is due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the effect of travel ball is also contributing.

HIGH SCHOOL BASEBALL

Travel ball has not only taken players away from high school ball, it has also tipped the balance in high school competition. Muskegon, Michigan, high school and travel baseball coach Red Pastor has said that travel ball has rendered high school baseball into the “haves” and “have nots.” Those teams that have travel-ball players have a significant advantage over teams with few or no travel-ball players. The competition becomes diluted as a handful of teams raise the bar that other teams can’t reach.9 According to Pastor, “You’re just not going to be successful anymore if your program doesn’t have at least four or five kids that played all year round and your pitcher better be one of them.”10

Benson High School in Omaha, Nebraska, serves as another example. Even with an enrollment of 1,400 students, the school did not have enough players to field a baseball team for three years. Those who wanted to play did so on a co-op team with another Omaha high school. In 2022, two Benson teachers were able to assemble a roster of 25 players, but only four had played baseball previously. Omaha World-Herald reporter Marjie Ducey wrote that none had even played Little League, nor had anyone on Benson’s roster played “select baseball through junior high like many of the other Metro Conference and Class A schools.” As a result, the Benson team did not fare well against those schools, and “sometimes the players get frustrated, especially when every game ends early because of the mercy rule.”11 Pastor observed many “mercy rule” games and attributed those lopsided losses to the winning team having “a ton of travel kids” and the losing team having few or none.12

Ohio high school officials in 2016 codified their concerns about travel ball’s interference with their baseball programs. The Ohio High School Athletic Association banned players and coaches from participating in any travel ball activities during the high school season.13

AMERICAN LEGION BASEBALL

Even more than high school ball, the other decades-long staple of teenage baseball, American Legion Baseball, has been hurt by travel teams. Because the seasons of American Legion and travel ball overlap, players are forced to choose. The best players opt for travel ball, where “[e]verybody’s going to these showcase baseball things where you go play in front of college coaches on the weekend,” explained Ryan Redeker, an Emporia, Kansas, baseball coach. “All the elite players have gone to that, so your Legion has gone down to your smaller type schools.”14

Between 2007 and 2017, 25 percent of American Legion baseball teams folded, and the number continues to dwindle. Some states lost up to 80 percent of their teams.15 From just 2016 to 2018, American Legion Baseball lost more than 300 teams.16 Maine typifies what’s happening to American Legion Baseball around the nation. Between 2016 and 2018 Maine lost 15 of its 33 teams. At its peak in 2007, the state had 48 teams.17 Galesburg, Illinois, is another microcosm of American Legion ball. After 60 years of fielding a team, the town’s American Legion Baseball shut down in 2017. Four years later, the Legion post revived the team, although coach Jeremy Kleine conceded he had trouble maintaining his initial roster of 18 players, with several missing games at times. “Last night (Tuesday) we were missing five players. Saturday (at Crawfordsville, Indiana) we’ll be missing five players,” said Kleine. “These days the players don’t put everything aside for baseball.”18 While some cite organizational problems within the American Legion and others cite changes in cultural attitudes, most agree that travel baseball siphons off the most talented players, leaving less serious players to populate high school and American Legion teams.19

THE PROMINENCE OF ELITE TRAVEL BASEBALL

“The travel or as some call them, the ‘showcase’ teams, have taken over,” proclaimed Pro Baseball Insider (PBI) in 2014.20 PBI echoes other youth baseball coaches and officials regarding reasons for the travel ball “take-over”: Players know that travel baseball offers the greatest chance of being scouted by a university or major league team, and the scouts know that travel ball tournaments save time and offer the greatest convenience in observing some of the best teen players in the nation. Former Southern New Hampshire University coach Ryan Copp questioned why he or any other scout would go to an American Legion game on a solitary field, when “I could go to one site with five fields and they would roll out a game every two hours.”21

Copp was referencing how tournaments have become the center stage for elite youth baseball teams. Regional tournaments sprang up in the early 1990s as the number of travel teams grew. Before that time, travel teams were sparse, but in that decade groups of parents and local businesses began forming private baseball teams for youngsters. Those teams often comprised the best players in the local grade schools, junior high, and high schools.22 Regional tournaments have since led to national tournaments. Youth sport entrepreneurs cashed in on the phenomenon and have built youth “baseball destinations,” such as Cooperstown All-Star Village. That facility in Oneonta, New York, about 10 miles south of Cooperstown, offers elaborate baseball camps and facilities, including lodging, a restaurant, a heated swimming pool, and other family-appealing amenities.23 The Village hosts week-long tournaments, as does another nearby destination, Cooperstown Dreams Park. Just south of Cooperstown, Dreams Park hosts week-long tournaments from June through August. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 100 teams from throughout the nation played there each week.24

The College World Series each June in Omaha is another baseball destination, but not just for college baseball teams and their fans. Claiming to be the “world’s largest youth baseball tournament,” the Slumpbuster Tournament is held concurrently with the College World Series. The 2023 tournament drew 630 teams from 40 states during the two weeks of the CWS and its festivities.25 But even though it may be the largest, even the Slumpbuster is not necessarily the most prestigious travel ball or showcase tournament. Several organizations, including the USSSA (United States Specialty Sports Association) and the AAU (Amateur Athletic Union), sponsor and sanction travel ball tournaments around the country.

But according to Sports Business Journal, the organization most associated with “showcase” tournaments that draw the best teen talent in baseball—and therefore the college and professional scouts to watch them—is Perfect Game. Based in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Perfect Game “has helped to remake the landscape of youth baseball.”26 Calling itself the “world’s largest” youth baseball scouting organization, Perfect Game not only holds national travel ball tournaments and talent showcases, but it has “built an entire culture around them,” according to SBJ. “The idea of an American baseball player getting to the major leagues, or even the minors, without having played at a Perfect Game event or generating a Perfect Game profile has become almost inconceivable,” the Journal’s Bruce Shoenfeld wrote.27

Since starting as an indoor baseball facility and youth select baseball sponsor 30 years ago, Perfect Game has grown into a $30-million-per-year business with more than 60 full-time employees and dozens of part-time scouts. “Tournaments that we started with 32 teams are now 400 teams,” said founder Jerry Ford.28 Perfect Game has built an information network of some of the most prominent national travel teams, and in doing so has provided information to college coaches and MLB scouts on teams and prospects. According to Perfect Game, 14,465 players who have played in one of their events were drafted by MLB teams, with 1,847 making it to the major leagues.29 Perfect Game epitomizes Klein, Macauley, and Cooper’s description of travel-team baseball: “a strong intersection with financial capital and summer travel coaches, college coaches, and major league scouts.”30

Perfect Game developed alongside the growth of large-scale youth elite baseball organizations. By 2005, Canes Baseball, Marucci Elite, and other programs had begun organizing teams and recruiting from coast to coast. The “nationalization” of travel teams was underway, and their “expansion and influence move[d] forward almost entirely unchecked.”31

But to what extent, if any, has the expansion and influence of elite travel ball helped African Americans to be drafted? We must identify the types of academies most likely to propel African Americans to the upper echelons of baseball and investigate differences between the types of teams that launch players into their post-high-school baseball careers.

METHODOLOGY

This study covered all players who were drafted by MLB teams in the first five rounds of the MLB Draft during the last 10 years (2013–22). The study was restricted to those rounds because of time and resource limitations. In addition, we looked at the highest-ranked prospects who, according to scouts and baseball prognosticators, have the greatest chance of joining the major league ranks. To explore one of Baker’s comments—that the number of African Americans being drafted by MLB teams bodes well— and to answer RQ1, the players from those first five rounds were categorized by race (White, African American, Latino or Hispanic American, Asian American, or Pacific Islander). To evaluate the statement that “academies,” or youth baseball programs, were producing African American players of high caliber, draftees were also categorized by the type of baseball team on which they played right before being drafted or playing college baseball.

Each player’s race was determined by skin color, hair type, and facial features. When in doubt, the primary coder researched surnames, particularly for Hispanic or Latino name origins using searches on the websites Forebears and House of Names.32,33 As a precaution against personal bias, a second coder (in addition to the primary coder) viewed a sample of MLB draftee photos (printed mostly from Perfect Game and college baseball websites) and also categorized the players by race. Cohen’s Kappa for inter-coder reliability was .90 for African American players, .86 for Hispanic and Latino players, and .94 for White players. (Asian and Pacific Islander players were so few that inter-coder reliability was not calculated.) All the Kappa values indicate strong agreement between the coders and thus the results of the racial categorization are acceptable.34

The next step in the methodology addressed RQ2 by comparing the results of RQ1 (the number of African Americans in the draft) with the percentages of players who are African American in youth travel baseball and college baseball. Results from studies on the racial composition of youth travel teams (for players, ages 9 to 1835) and the University of Central Florida’s Racial and Gender Report Card on college sports provided those percentages.36

While RQ2 deals tangentially with the role of baseball academies, RQ3 was designed to delve more deeply into Baker’s acknowledgment of that role. This meant determining the extent to which African American draftees, compared with draftees of other races, played travel ball in the year or years before being drafted or entering a college program. Previous research shows that the wider a geographic area a showcase or travel team’s participants represent, the greater the team’s prominence or stature.37 That stature also depends on the travel team’s connections to college coaches and major league scouts, an aspect that will be discussed below.

To address RQ3 and Baker’s assertion, draftees’ travel teams were categorized based on the sizes of the geographic areas which the team roster reflected:

- Urban—players came from one city or its suburbs

- Statewide—players came from different areas of the same state

- Regional—players came from different states, but within the same geographic region

- Multi-regional—players came from two or three geographic regions

- National—players represented all four geographic US regions

This study used US Census Bureau guidelines to define the four regions—West, Midwest, Northeast, and South—and the states included in them.38

If a high school team was a player’s last stop before entering college or the draft, that team was considered as one city, since those high school players usually live in the same metropolitan or suburban area. The exceptions were national secondary education schools, like IMG Academy in Florida.

For a region to be counted as being represented on a team, at least two players had to come from a state or states within that region. This requirement was meant to avoid circumstances in which a team accepted a player solely because of a friendship or family relationship with another player or coach on the team. This study is designed to focus on players who were recruited solely because of their talent level or selected via tryout, and the two-player guideline increases the likelihood of that.

In looking at a travel team’s role in creating paths for their players to college and professional baseball, semi-structured interviews were conducted via telephone with two coaches and a former coach who now coordinates travel team tournaments. Those interviews allowed coaches to elucidate aspects of their participation in and their teams’ impact on their young charges’ futures. Their responses also add perspective to the scant research literature on travel team coaches.

RESULTS

Between 2013 and 2022, 1,646 players were selected in the first five rounds of the MLB amateur draft, 1,631 of whom were included in the study. (15 Canadian players were excepted.) African Americans constituted 12.3 percent of the included draftees, while White players comprised 79.4 percent, Hispanic/Latinos 7.8 percent, and Asian American and Pacific Islanders less than 1 percent. These percentages address RQ1, but mean little without putting them in context. Nationally, African Americans comprise 14.2 percent of 18–24-year-old males, the age group covering the vast majority of those taken in the amateur draft.39 Trailing the national average by less than 2 percent may not seem encouraging, but the percentage of draftees who are African American has outpaced the proportion of players who are African American at elite levels of competition during the past decade, from youth travel ball to MLB.

That lends credence to Baker’s assertion that more African Americans are being drafted. However, tracking that percentage annually from 2013–22 tempers that finding. During that time span, the annual percentages have fluctuated.40 In the 2013 draft, African Americans comprised 15.8 percent of the first five rounds of players, while in 2022 it was 14 percent. In between, the percentage has ranged between 8.5 percent (2017) and 16.7 percent (2015).

Regardless of their inconsistency, those percentages still remain well above the proportion of African Americans coming down baseball’s talent pipeline, the focus of RQ2. A 20-year study covering 1,064 youth travel teams (more than 12,000 players, ages 9–18) in 40 states shows that only 3 percent of those rosters were African Americans.41 Another study of photographs of 3,263 teams (more than 38,500 players, mostly 12 years old) that played at tournaments at the Cooperstown All-Star Village and Cooperstown Dreams Park from 2014 through 2022 showed that 5.4 percent of those players were African American.42 The percentage remains in the single digits in the college ranks. In NCAA Division I baseball, African Americans made up 4.2 percent of the players in 2022.43 And in Major League Baseball, 6.3 percent of the 2023 26-man rosters are African American.44

Evidence to support Baker’s faith in youth baseball academies, however, appears justified, despite the low percentage of African Americans in travel ball. At least 90 percent of the draftees in this study played youth travel ball, with no significant difference between races. The other 10 percent played high school baseball and may have also played travel ball, but the scant information about their playing histories didn’t include that experience.

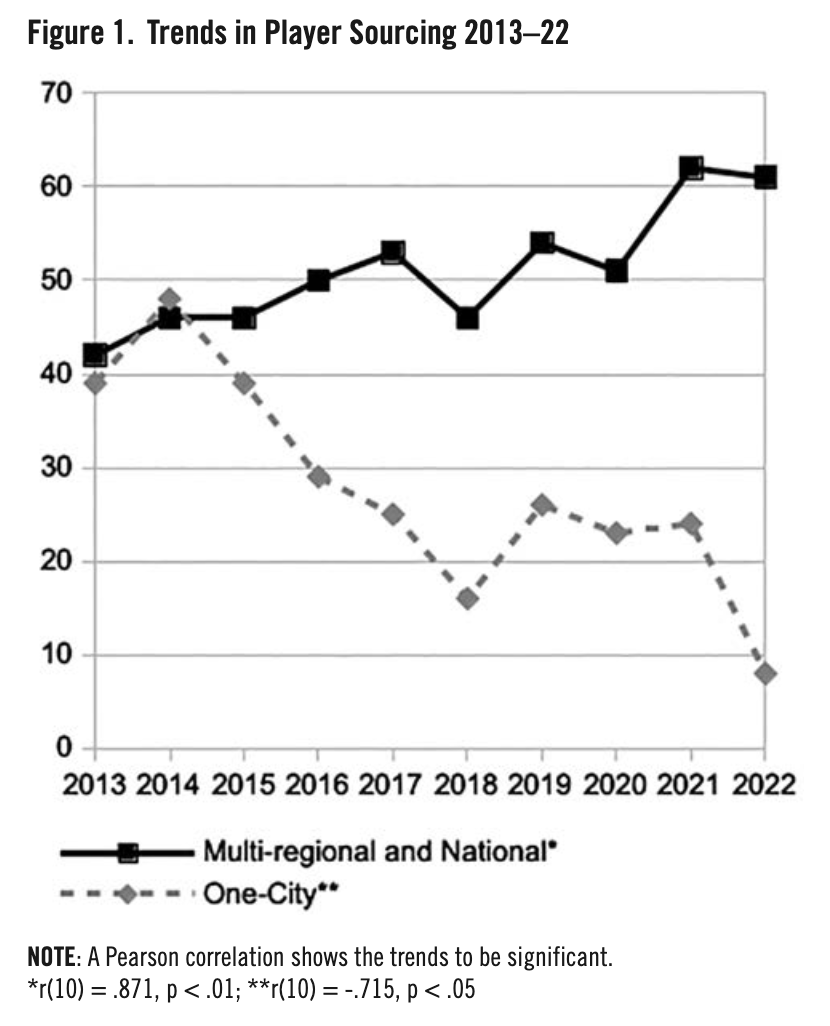

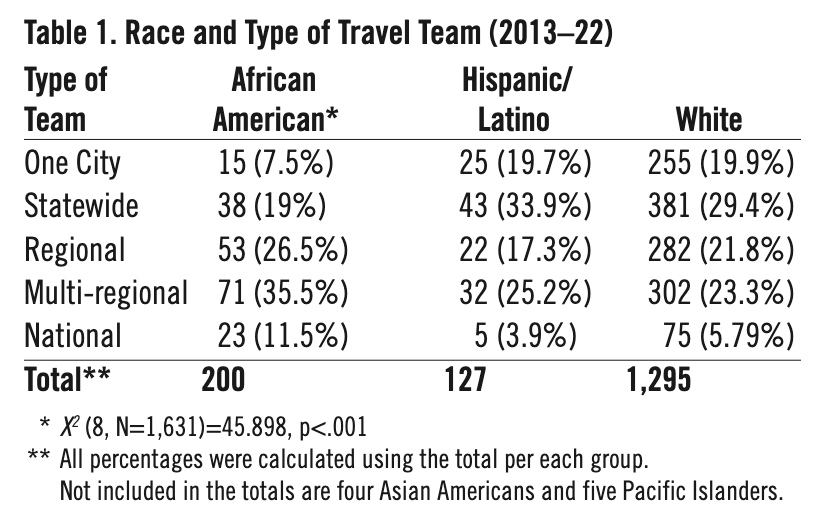

While the findings show travel baseball to be a steady influence in the draft over the past 10 years, elite youth competition continues to evolve, as demonstrated by the preponderance of multi-regional and national teams. Figure 1 illustrates that those teams are growing as sources of players, particularly African Americans, for college and eventually the MLB Draft. That trend provides detail in answering RQ 3 and adds substance to Baker’s point. African American draftees were significantly more likely than Hispanic/Latino and White draftees to have played on a regional, multi-regional, or national team before being drafted. (See Table 1.) More than 70 percent of African American draftees played on one of those teams as their “last stop” before college or the pros. Approximately 50 percent of White draftees and 46 percent of Hispanic/Latino draftees played on regional, multi-regional, or national teams. (Note that although Asian Americans and Pacific Islander draftees are included in the total number of players (1,631), they did not constitute a separate racial category, because their low number—less than 1 percent—could confound overall results in a Chi square calculation.)

Examining the individual categories of regional, multi-regional, and national teams adds more detail. Of the 357 draftees from regional teams, 66 percent played on southern teams. Approximately 13 percent played on teams from the West, 12 percent on Midwestern teams, and 9 percent on Northeastern teams. But there were no significant racial differences in which region draftees played. White and Hispanic players were as likely to play on Southern teams as African Americans were, and the same was true for all other regions.

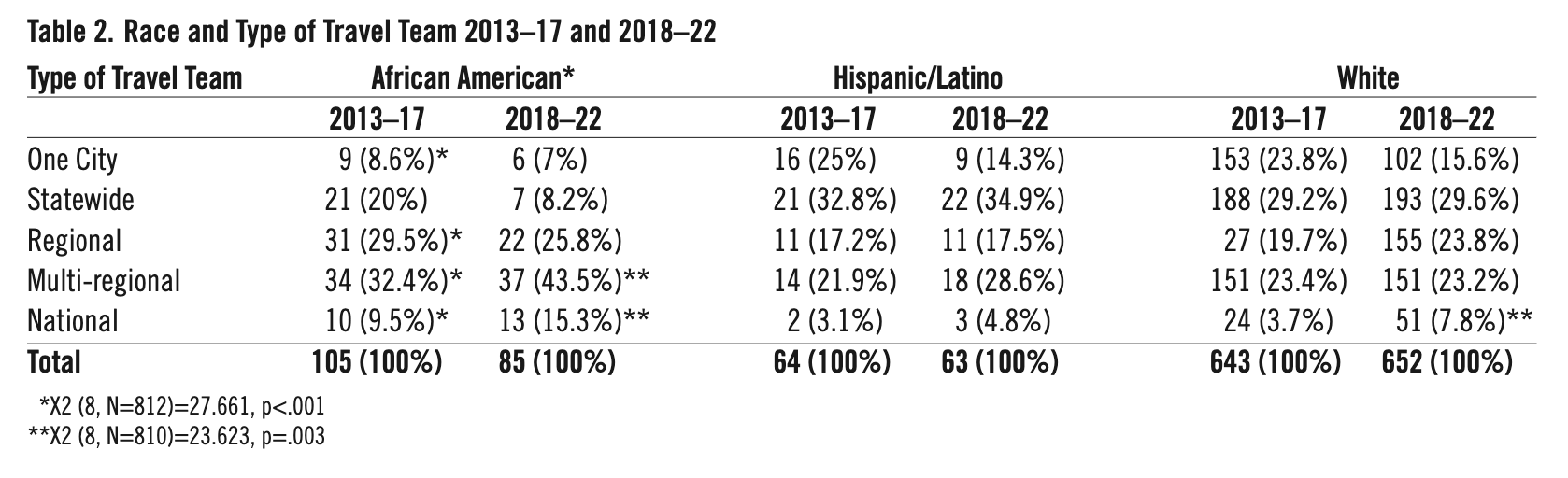

Multi-regional and national teams are a different matter. Their influence as sources of African American talent has grown in the last five years of the decade. From 2018–22, more than half of African American draftees, compared with 31 percent of White and 33 percent of Hispanic/Latino draftees, came from multi-regional and national teams. Those teams produced 50 African American draftees during that period, compared with 44 from 2013–17. National teams also grew as a source of White players, with the number of those players doubling during the second half of the decade. (See Table 2.)

(Click image to enlarge)

Conversely, teams from one city or urban area produced few African American draftees, with just over 7 percent playing their last travel ball on urban categorized teams. (See Table 1.) Almost 20 percent of White draftees played on single-city teams, as did the same percentage of Hispanic/Latinos. But these teams are losing their influence as sources of MLB draftees. While numbers for multi-regional and national teams as sources of MLB draftees are increasing, the number of teams whose rosters represent only one urban area is decreasing. (See Figure 1.)

So has the number of draftees who played on those teams. In 2013, five of the 26 African American players (19 percent) in the first five rounds of that year’s draft came from an urban team and eight (31 percent) came from national and multi-regional teams. The percentage of African Americans from urban teams could be even higher in MLB drafts before 2013, when rules for compensatory picks were changed and competitive balance picks were added. A preliminary analysis of the first five rounds of the 2012 draft showed that urban teams (consisting mostly of high school and American Legion teams) were the last known stops before college or professional baseball for almost 70 percent of African Americans drafted that year. Only 9 percent came from multi-regional and national teams.

More than 10 years later, few African American draftees come from urban teams. Those teams accounted for only three of the 23 African American draftees (13 percent) in the 2022 draft, while national and multi-regional teams accounted for 13 (57 percent). As such, some of the teams with the largest geographic scope have emerged as leaders in getting African Americans to the next level of competition, be it college or pro baseball. In the last 10 years, Canes Baseball, a national travel team organization, had 11 African American players taken in the first five rounds of the MLB amateur draft, more than any other national or multi-regional program. Marucci Elite and The Royals Scout Team each had five African American alumni make the draft, while the Ohio Warhawks contributed four such players. The IMG Academy, MLB Breakthrough Series, and Blackhawks National each contributed several African American alumni to the draft.

As previously noted, national, multi-regional, and regional teams accounted for the majority of African Americans in the first five rounds. To attract top talent, some travel teams offer incentives, especially financial assistance. Researchers, journalists, youth baseball, officials, and MLB players and officials have cited the expense of travel baseball as a major obstacle to African American participation. Some multi-regional and national travel teams not only remove that obstacle, but also cover living expenses, and in some cases, educational costs for players.

DISCUSSION

Results from this research justify Baker’s hope that larger numbers of African Americans are poised to join the rosters of Major League Baseball teams. Although the year-to-year percentage of major league draftees who are African American is uneven, a trend toward more multi-regional and national teams as sources of draftees bodes well, since a greater percentage of African Americans, compared with other races, come from those teams. The diminishment of travel teams from single urban areas or cities adds perspective to the growth of multi-regional and national teams. Rick Goff, founder of the Michigan Sports Academy and now director of The Travel Ball Select National Championship, noted that in the late 1990s and early years of the next decade, travel teams were localized and most played regionally “within 3 or 4 hours from home… There were very few of what we would call national [teams] that were willing to travel anywhere in the country, and we were one of those national teams.”45

Goff, who primarily coached travel teams for 14-year-olds and younger, built his rosters partly through scouting by his own players. His players would tip him off to talented players on other teams at tournaments: “A player would talk to one of my kids and my kids are like, ‘Hey, we’re always looking for players. Come play with us.’”46 Goff would then watch the player at some point during the tournament before extending an invitation for the following season. “One time I had kids who came out of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Chicago, Fort Wayne, Madison. They would come and play with me full-time in Michigan; and they just traveled wherever we traveled to play.”47

While those programs have eroded high school and American Legion baseball, they have created wider portals for entry into high-level youth competition. Bob Herold, an IMG Academy coach, said those portals have benefited African American players. His organization often takes its cues from MLB, which shows “a lot of interest in getting those guys [African Americans] to the Big Leagues.”48

Herold, a former minor league manager and coach with the Kansas City Royals and Pittsburgh Pirates, said MLB is giving African American players extra scrutiny. “MLB is going to make sure that if they get an African American that’s a good athlete, they’re going to give him every opportunity to play at higher levels,” he said. “Baseball doesn’t want to be out of line with society.”49

Herold points to IMG alumnus Elijah Green, the fifth overall pick in the 2022 MLB amateur draft, and one of four African Americans in the first five selections. Herold said IMG coaches recruited Green after they saw him play on an opposing team. “IMG pulled him off to the side and said, ‘We’ll pay everything here for the school year. We know you’re going to be drafted,’” Herold said. “He would have been drafted whether he stayed in Orlando or here.”50

Green also serves as an example of how IMG and other national programs compete for the best young baseball talent in the nation. Herold said IMG baseball prospects know that they “don’t pay a dime” to attend the academy, an attraction for those who can’t afford the usual expenses of travel ball.51 The Ohio Warhawks follow the same strategy. The Warhawks website proclaims they “have never, and never will charge any player fees.”52 The Warhawks give players, “regardless of their financial background, a free and equal opportunity to improve their baseball skills and increase their chances of advancing to higher levels of baseball.” The Warhawks also own a 4,000-square-foot facility that contains lodging for coaches and players, training and shower facilities, and a laundry and a recreation area.53

The MLB Breakthrough Series, in which several first-round African American draftees played (i.e. KeBryan Hayes and Addison Russell, among others), also covers expenses for players. The Breakthrough Series, co-sponsored with USA Baseball, not only supports players throughout the season, but also offers players “additional development and instructional opportunities throughout the year.”54 Brooks, Knudson, and Smith note that the intentions of such programs are not entirely altruistic: “[T]he recruitment of talented youth athletes of color by predominantly White high schools [and youth sports institutions] is an exchange that presumably benefits the youth of color,” but the institutions also benefit.55 The researchers say that recruiting the best Black baseball talent gives a team “bragging rights” and “a perception of inclusion, and revenues.” Indeed, national programs hone that image and tout their “bragging rights.”56 The Motor City Hit Dogs, for example, calls itself “one of the top 5 programs nationally,”57 and Marucci Elite (sponsored by the Marucci baseball equipment company) claims to be “one of the nation’s most prolific amateur baseball organizations.”58

Some organizations imply their national prominence by stressing the high standards they set for their players and the stringent process for players trying to make a team. To be considered for a tryout for Canes Baseball, players must file an application form which asks for information such as pitch velocity, “pop time” (for catchers), 60-yard dash time, current travel team, talent showcases attended, and college coaches or pro scouts who have contacted them. The application cautions: “Please understand that talent of only the highest level will be considered a potential prospect and not all submissions will receive a response.”59

Canes coach Donald Murray said high-profile travel programs can afford to be picky. “I’m in competition for players,” Murray said, but “I don’t have to accept guys who don’t want to compete and who aren’t respectful.”60

National programs can maintain such stringency in both talent and character because of their constant recruiting and roster building. “These top level travel teams in today’s world will recruit kids all year long from other teams, other states,” Goff said, and the teams “don’t care if you’re White, Black, Hispanic or if you’re something else. If you can play baseball, you’re in.”61 Herold agreed, but with a caveat: “Particular organizations really make it a point of getting African Americans.”62

To be sure, the Canes, Marucci Elite, and other national and multi-regional programs are creating more opportunities and entry points for African Americans and other players. The programs are throwing a wider net to get talent and expanding their base of players by creating more teams. Marucci Elite fielded 50 travel teams in 2022.63 In 2020, Canes Baseball fortified its regional network of teams by establishing “Canes of the Great Plains” and calling it “a true national pipeline running throughout the region.”64 The region includes Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, and Missouri. As a result, Canes Baseball absorbed the Wichita (KS) Vipers and another travel team organization, SWAT Academy, in Oklahoma City.65 In that same year, Canes Baseball also assumed management of the Carrollton City (GA) Recreation Baseball League.66

Blackhawks National has also built its own pipeline to stock talent. Blackhawks National sponsors teams for grade-school-aged and junior high school players.67 Canes Baseball even looks for prodigies in preschool, offering baseball activities for children as young as three. Those children can then graduate to T-ball, then to leagues with pitching machines, before moving on by age 11 to “live” pitching.68 As regional, multi- regional, and national travel team organizations expand, so does the symbiosis between the best young baseball talent and the “gatekeepers” to the college and professional ranks (i.e. college coaches and MLB scouts). The “go-between” is the travel coach. The coach brings that talent and the gatekeepers together. His team attracts talent because of its connections to colleges and major league scouts, and that attraction becomes self-perpetuating, since those coaches and scouts will go where the talent is. To expose its players to a wide swath of post-secondary coaches, Marucci Elite “partners” with 77 university and college baseball programs, including 39 in Division I.69

These relationships have created what Klein and colleagues call the “professionalization” of travel baseball through “the presence of heavy professional scouting and collegiate recruiting during summer travel baseball.”70 Those researchers contend that this professionalization gives travel team coaches considerable influence and leverage in the fate of their players. The players and their families depend on the coaches’ connections and counsel in navigating through the college or MLB recruitment process. “Thus, the travel coach becomes an important figure in the youth and high school baseball socialization process.”71

As they have evolved, travel teams with a broad geographic base have concentrated the talent pool and made it less likely for players on single city teams to be scouted by colleges or pro teams. That goes especially for African Americans. As noted previously, research shows that approximately 3 percent of those on youth select teams in the Slumpbuster Tournament were African American.72 The majority of those teams were single-city teams, and such teams tend to be rooted in the suburbs. Thus, it should not be surprising that so few African American players came to college or the pros from single-city teams. That may also explain why the diminishment of high school and American Legion Baseball has had little, if any, impact on the number of African Americans being selected in the first five rounds of the draft. Simply put, there aren’t many African Americans on those local teams to be drafted.

CONCLUSION

What Klein refers to as the “professionalization” of youth baseball has happened alongside the nationalization of youth baseball. An amalgamation of wide-scale travel team “brands” and a complex network of information centers, travel team organizations, college coaches, and MLB organizations are exposing more African American prospects than their numbers show in youth elite-level baseball.

In 2013 and 2015, the percentage of African American draftees in the first five rounds exceeded the national percentage of 18–24-year-old males who are African American, but that has not happened in the last seven years (although 14 percent in 2022 was closest since 2015). A long-term trend in growth has not materialized thus far. Perhaps Baker’s comments about more African Americans in the draft should be approached with cautious optimism, as should his hope that travel baseball will provide a consistent and lasting source of African American prospects.

While this study determined the types of baseball academies from which African American draftees came, it does not identify what influenced those draftees to prevail as among the top talent, as assessed by MLB teams. Previous research has described factors related to African American youths’ sports and recreational choices, but framing them in the context of the MLB draft requires further research. That research should explore more deeply the nuances of how elite youth baseball programs form allegiances and work closely with college and university baseball teams and professional leagues to identify talent. What can be identified in this study are the characteristics shared by those programs that are most successful in contributing African American players to the highest rounds of the MLB draft. There are four such similarities:

One is the broadening of their player base, both in numbers and geographically. The Canes, Marucci Elite, and The Blackhawks have developed extensive “feeder” programs by sponsoring teams for grade-school-aged players or by franchising teams in different areas of the country. These programs also have extensive coaching and administrative staffs, as well as their own practice and training facilities. A second characteristic is the aggressive recruitment of talent. As Goff, Herold, and Murray noted, travel team programs compete for talent in various ways. Social media apps and websites have facilitated regional and national recruitment by allowing coaches and far-flung teammates to communicate easily. Third, coaches in the programs forge relationships with college coaches and pro scouts and provide player access to them. As such, the travel coaches are the link between travel ball and baseball beyond high school. They serve as the linchpins to a players’ baseball future.

The fourth characteristic, although not shared by all national programs, is defraying costs to provide African American players with baseball experiences “that they might not otherwise afford, that would not be open to them socially, if they were not elite athletes.”73 The MLB Breakthrough Series has made financial aid a cornerstone of its related programs, like the Dream Series showcase, that gives African American players in high school a chance to perform in front of MLB scouts.

The extent to which other large-scale travel ball programs share these characteristics or contribute to the number of African American draftees is unknown because of the limited number of players in this study. At the very least, coaches, family members, and mentors of talented, motivated and young African American baseball players can use these characteristics as guideposts in directing their players to ever higher levels of baseball. This could be particularly useful for parents in finding youth baseball organizations that tap into larger organizations, offer financial assistance, and offer the eventual likelihood of exposure to coaches and scouts. Some researchers say that too often parents cede control of their sons’ futures to travel and college coaches, instead of taking a proactive role in their sons’ baseball career decisions.74

Expanding this research beyond the first five rounds of the MLB amateur draft and analyzing drafts years, if not decades, before 2013 might uncover other characteristics common to teams on which African Americans played before college or the draft. The ideal would be to determine the races and playing histories of the MLB draftees in all 40 rounds from 2013–19 (5 rounds in 2020, and 20 rounds since). Extending the time span to include more MLB drafts of the past would add historical perspective and might provide definitive evidence to support Baker’s opinion that more African Americans are reaching the highest rungs of youth travel baseball and the MLB Draft.

Despite this study’s limitations, the qualitative nature of the draft (i.e. the best are taken first) gives heft and purpose to examining the first few rounds. Those rounds might indicate how African Americans figure in the draft strategies and interests of MLB teams. As Coach Bob Herold said, MLB is paying attention to African American players, who “are going to get a shot to play” upon reaching the threshold to college and pro baseball.75 Initiatives like the MLB Breakthrough Series and high draft picks by MLB teams seem to support Herold’s observations. If so, that attention could explain why the percentage of MLB draftees who are African American exceeds the percentage in travel ball, college ball, and the major leagues. So far, that high percentage of draftees has not yet translated into an increase in African Americans on major league rosters. Herold thinks it will: “You heard Dusty Baker say it. Help is on the way.”76

Notes

1 Jalen Brown and Justin Gamble, “Major League Baseball Has a Diversity Problem, Experts Say. This Year’s World Series is Proof ,” CNN, November 2, 2022, as broadcast by WLFI, Lafayette, IN, https://www.wlfi.com/news/national/major-league-baseball-has-a-diversity-problem-experts-say-this-years-world-series-is-proof/article, accessed February 15, 2023.

2 Ron Wynn, “World Series Lack African American Participation,” Tennessee Tribune, November 3, 2022, https://tntribune.com/world-series-lack-african-american-participation/, accessed February 15, 2023.

3 Wynn, “World Series Lack African American Participation.”

4 David Waldstein, “MLB Works to Build a New Generation of Black American Players,” The New York Times, January 17, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/17/sports/baseball/mlb-dream-series.html, accessed February 20, 2023.

5 David C. Ogden, “Specialization in Youth Baseball: Channeling Players to Higher Competition or Choking Youthful Desire?” Paper presented at the 22nd annual Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, June 2-4, 2010, Cooperstown, NY.

6 Les Edgerton, Perfect Game USA and the Future of Baseball: How the Remaking of Youth Scouting Affects the National Pastime (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009).

7 Nick Stevens, “NC High School Sports Participation Declined In All But 5 Sports After Pandemic” High School OT, September 22, 2022, https://www.highschoolot.com/nc-high-school-sports-participation-declined-in-all-but-5-sports-after-pandemic/20487621/, accessed January 15, 2023.

8 Laura Handby Hudgens, “The Decline of Baseball and Why It Matters,” The Huffington Post, December 6, 2017, accessed January 15, 2023.

9 Josh VanDyke, “How Michigan Travel League Programs Have Created Competitive Gap in High School Baseball, Softball,” MichiganLive, September 22, 2021, https://www.mlive.com/highschoolsports/2021/05/how-travel-league-programs-have-created-seismic-talent-gap-in-prep-baseball-softball.html, accessed February 20, 2023.

10 VanDyke, “How Michigan Travel League Programs.”

11 Marjie Ducey,“Benson Baseball is Reborn,” Omaha World-Herald, January 19, 2023, https://omaha.com/sports/high-school/benson-baseball-is-reborn-with-the-help-of-two-teachers-and-players-determination/article, accessed February 20, 2023.

12 VanDyke, “How Michigan Travel League Programs.”

13 Jerry Snodgrass, “This Week in Baseball—2016,” The Ohio High School Athletic Association, https://www.ohsaa.org/sports/bb/boys/TWIBAdviceforSummerTeamCoaches.pdf, accessed January 10, 2023.

14 Christopher Adams, “What Has Happened to Legion Baseball?” Emporia (KS) Gazette, July 28, 2022, http://www.emporiagazette.com/sports/article_3999e6f4-0ea4-11ed-a3e2-03b7182e40fc.html, accessed January 15, 2023.

15 Adams,“What Has Happened to Legion Baseball?”

16 Adam Feiner, “Sad Demise of Legion Ball,” Shaw Local News Network (IL), August 3, 2018, https://www.shawlocal.com/2018/08/03/sad-demise-of-legion-ball/a3v0ony/, accessed February 20, 2023.

17 Steve Craig, “American Legion Baseball Is on the Decline in Maine,” Portland (ME) Press Herald, June 21, 2018. https://www.pressherald.com/2018/06/21/american-legion-baseball-is-on-the-decline-in-maine/, accessed February 21, 2023.

18 Mike Trueblood, “They’re Back! What to Know as American Legion Returns to Galesburg After 4-year Hiatus,” Galesburg (IL) RegisterMail, July 9, 2022, https://www.galesburg.com/story/sports/2022/06/09/galesburg-american-legion-baseball-returns-2022-after-4-year-hiatus/7566873001/, accessed February 20, 2023.

19 Frank Fitzpatrick, “American Legion Baseball: The Summer Tradition Slowly Fading Away,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 27, 2019, https://www.inquirer.com/high-school-sports/american-legion-baseball-decline-military-aau-showcases-20190727.html, accessed January 15, 2023.

20 “Travel Baseball vs. American Legion Baseball—What’s the Difference?”, Pro Baseball Insider, 2014, https://probaseballinsider.com/travel-baseball-vs-american-legion-baseball-whats-the-difference/, accessed July 19, 2020.

21 Craig, “American Legion Baseball Is on the Decline in Maine.”

22 David C. Ogden, “The Welcome Theory: An Approach to Studying African-AmericanYouth Interest and Involvement in Baseball.” Nine.- A Journal of Baseball History and Culture 12, no. 2 (Spring 2004): 114-22. Also see David C. Ogden,“It’s Suburban and Serious: The State of Youth Select Baseball in the U.S.”Paper presented at the 10th Annual Indiana State University Conference on Baseball in Literature and Culture, Terre Haute, IN, April 15, 2005; Edgerton, Perfect Game USA and the Future of Baseball.

23 Cooperstown All Star Village, https://cooperstown.com/, accessed March 1, 2023.

24 Cooperstown Dreams Park, https://www.cooperstowndreamspark.com/home/, accessed March 1, 2023.

25 Omaha Slumpbuster, https://www.omahaslumpbuster.com/, accessed August 19, 2023.

26 Bruce Shoenfeld, “Remaking the Landscape of Youth Baseball,” Sports Business Journal, August 5, 2019, https://www.sportsbusinessjournal.com/Journal/Issues/2019/08/05/Leagues-and-Governing-Bodies/Youth-baseball.aspx, accessed February 20, 2023.

27 Shoenfeld, “Remaking the Landscape of Youth Baseball.”

28 Shoenfeld, “Remaking the Landscape of Youth Baseball.”

29 These numbers are given on the Perfect Game website (https://www.perfectgame.org/articles/View.aspx?article=21814#:~:text=To%20date%2C%20more%20than%201%2C847,First%2DYear%20Amateur%20Player%20Draft., accessed August 31, 2023). See also Shoenfeld, “Remaking the Landscape of Youth Baseball,” who cites 12,000 draftees via Perfect Game.

30 Max Klein, Charles Macaulay, and Joseph Cooper, “ The Perfect Game: An Ecological Systems Approach to the Influences of Elite Youth and High School Baseball Socialization,” Journal of Athlete Development and Experience2, no. 1 (March 2020): 14-35 (quote on 22).

31 Robert Nicholas Itri,“Understanding the Impact of Travel Sports on High School Athletes’ Perception of High School Sports” (doctoral dissertation, Graduate School of Troy University, Troy, AL, 2021), 2.

32 Forebears, https://forebears.io/surnames/.

33 House of Names, https://www.houseofnames.com/.

34 Mary L. McHugh, “Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic,” Biochemia Medica, (October 22, 2012): 276-82.

35 David C. Ogden, “Tracking the Decline: Results of a Two-Decade Study of African Americans in Youth Select Baseball.” Paper presented at the 28th annual Nine Spring Training Conference, March 13, 2021, Tempe, AZ.

36 Richard Lapchick, 2022 Racial and Gender Report Card: College Sport, The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport (Orlando: University of Central Florida, March 22, 2023), https://www.tidesport.org/_files/ugdZc01324_d0d17cf9f4c7469fbe410704a056db35.pdf, accessed March 22, 2023.

37 See Shoenfeld, “Remaking the Landscape of Youth Baseball”; Adams, “What Has Happened to Legion Baseball?”, and Edgerton, Perfect Game USA and the Future of Baseball.

38 “Census Regions and Divisions of the United States,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf, accessed January 7, 2023.

39 “Sex by Age,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://data.census.gov/table?g=0100000US,$0400000&d=ACS+5-Year+Estimates+Detailed+Tables&tid=ACSDT5Y2021.B01001B, accessed January 7, 2023.

40 Percentages based on MLB Draft Tracker, https://www.mlb.com/draft/tracker, and photos and information from Perfect Game, https://www.perfectgame.org/, and various college Web sites.

41 Ogden, “Tracking the Decline.”Results of the survey of 213 teams at the 2021 and 2022 Slumpbuster Tournaments were added to the results presented at the Nine Spring Training Conference.

42 The results of this study have not been published. Team photographs from the Cooperstown Dreams Park Web site (https://www.cooperstowndreamspark.com/home/) and Cooperstown All Star Village, (https://cooperstown.com/) were analyzed for racial composition June to September 2022. A second coder analyzed a sample of the photographs and a Cohen’s Kappa for intercoder reliability was .88 for African Americans.

43 Lapchick, 2022 Racial and Gender Report Card: College Sport, 70.

44 Richard Lapchick, 2023 Racial and Gender Report Card: Major League Baseball, 40, https://www.tidesport.org/_files/ugd/ac4087_3801e61a4fd04fbda329c9af387ca948.pdf, August 19, 2023. This percentage lags far behind that of other major league team sports. “Blacks or African Americans,” according to Lapchick, constitute more than 70 percent of players in the National Basketball Association, 2023 Racial and Gender Report Card: National Basketball Association, 59, https://www.tidesport.org/_files/ugd/c01324_abb94cf8275d49499e89fa14f0777901.pdf, August 19, 2023. In 2022 Blacks or African Americans comprised more than 56 percent of players in the National Football League and almost 25 percent of Major League Soccer players, The Complete 2022 Racial and Gender Report Card, 20, 16, https://www.tidesport.org/_files/ugd/ac4087_31b60a6a51574cbe9b552831c0fcbd3f.pdf, August 19, 2023.

45 Rick Goff, telephone interview, January 21, 2023.

46 Goff, telephone interview.

47 Goff, telephone interview.

48 Bob Herold, telephone interview, January 16, 2023.

49 Herold, telephone interview.

50 Herold, telephone interview.

51 Herold, telephone interview.

52 Ohio Warhawks Baseball, “History,” https://ohiowarhawks.net/Pages/1-column.htm, accessed March 1, 2023.

53 Ohio Warhawks Baseball, “History.”

54 MLB Breakthrough Series, “What Is the Breakthrough Series?”, https://www.mlb.com/breakthrough-series, accessed March 1, 2023.

55 Scott N. Brooks, Matt Knudtson, and Isais Smith, “Some Kids Are Left Behind: The Failure of a Perspective, Using Critical Race Theory to Expand the Coverage in the Sociology of Youth Sports, Sociology Compass 11, no. 2 (October 31, 2016): 1-14 (quote on 9).

56 Brooks, Knudtson, and Smith, “Some Kids Are Left Behind,” 7.

57 Motor City Hit Dogs, “Our Mission,” https://motorcityhitdogs.com/about-us/our-mission/, March 1, 2023.

58 Marucci Elite, “Marucci Elite,” https://maruccisports.com/elite/, accessed January 16, 2023.

59 The Canes Baseball Club, “Prospect Form,” https://canesbaseball.net/prospect-form/, February 20, 2023.

60 Donald Murray, telephone interview, February 3, 2023.

61 Goff, telephone interview.

62 Herold, telephone interview.

63 Marucci Elite Baseball, “Our Franchise Club Teams,” https://maruccisports.com/organizations/, January 16, 2023.

64 The Canes Baseball Club, “Canes Baseball Announces Addition of Canes of the Great Plains,” https://canesbaseball.net/canes-baseball-announces-addition-of-canes-of-the-great-plains/, accessed February 20, 2023.

65 The Canes Baseball Club, “Canes Baseball Announces Addition of Canes Oklahoma,” https://canesbaseball.net/canes-baseball-announces-addition-of-canes-oklahoma/, accessed February 20, 2023.

66 The Canes Baseball Club, “Canes Southeast,” https://www.canessoutheast.com/, accessed February 20, 2023.

67 Blackhawks National Baseball, https://blackhawksnational.com/, January 21, 2023.

68 The Canes Baseball Club, “Canes Southeast.”

69 Marucci Elite Baseball, “Marucci College Partners,” https://maruccisports.com/colleges/, February 20, 2023.

70 Klein, Macaulay and Cooper, “The Perfect Game: An Ecological Systems Approach,” 28.

71 Klein, Macaulay and Cooper, “The Perfect Game: An Ecological Systems Approach,” 25.

72 Ogden, “Tracking the Decline.”

73. Brooks, Knudtson, and Smith, “Some Kids Are Left Behind,” 6.

74 Klein, Macaulay and Cooper, “The Perfect Game: An Ecological Systems Approach,” 24.

75 Herold, telephone interview.

76 Herold, telephone interview.