May 31, 1858: Winthrop tops Olympic in first match game played under ‘Massachusetts’ rules

Imitation, as the expression goes, is the sincerest form of flattery. It was the former, and most certainly not the latter, that the Massachusetts Association of Base Ball Players (MABBP) had in mind when they created a standard set of rules in May of 1858. One year earlier, a group of clubs from the cities of New York and Brooklyn, brazenly calling themselves the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP), had codified the rules for their version of the game.1 These rules ultimately helped establish the “New York game” as the progenitor of modern baseball.

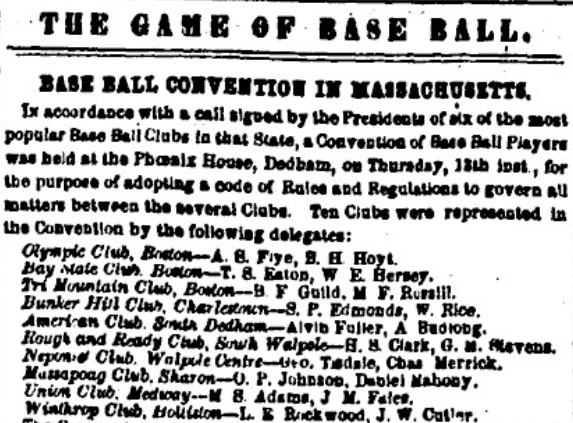

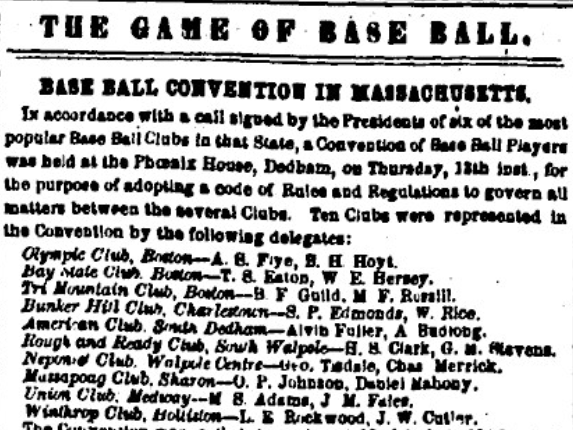

Looking to “improve and foster the Massachusetts game,” six Boston-area clubs organized a convention in Dedham, a Boston suburb, on May 13, 1858.2 Representatives from the 10 participating clubs formed the MABBP, elected officers, and agreed to a constitution, bylaws, and “rules and regulations of the game of base ball.”3

Unlike the NABBP, which had agreed to some requirements new to some of its members, the MABBP adopted rules that closely reflected how their members played. One bedrock of the Massachusetts game that the MABBP retained was defining the end of a game as the moment when a certain number of tallies (runs) were scored, a value they set at 100. The NABBP had jettisoned a similar practice common to the New York game, instead specifying that their games ended after nine innings, absent a tie – a stroke of genius that remains a defining feature of the sport to this day.

In addition to “100 tallies [constituting] the game,”4 rules enshrined by the MABBP that were unique to the Massachusetts game included:

- The bases were arranged in a square pattern, with the striker (batter) standing midway between home plate and first base.

- Throwers (pitchers) stood 35 feet from the batter.

- Bases were wooden stakes four feet high.

- Teams consisted of 10 to 14 players.

- Fielders could retire baserunners by striking them with the ball (“soaking”).5

- Balls must be “caught flying” to count as outs (no bound outs).6

- The batting team was retired once a single out was recorded (also known as the “one out, all out” rule).

On Monday, May 31, two weeks after the conventioneers departed for home, a pair of clubs that helped organize the conclave played the first match under the new MABBP rules: Boston’s Olympic Club and the Winthrop Club of Holliston.

The Winthrop Club, one of several Whig social clubs by that name across the commonwealth,7 hailed from a town located about 30 miles southwest of Boston Common. Named for seventeenth-century Harvard College benefactor Thomas Hollis, Holliston was also home to the burgeoning community of Mudville, a neighborhood settled in the 1850s by Irish railroad workers. Many believe that Holliston was the setting for Ernest Thayer’s baseball epic, Casey at the Bat, penned in 1888.8 It is unclear when the Winthrop Club of Holliston began playing base ball. Surviving newspaper archives make no mention of any matches played by the team before this one.

On the other hand, we know that the Olympic Club played match games as early as September 1853.9 In June of 1857, Olympic were swept by the Massapoag Ball Club of Sharon in a best-of-five tournament that the Boston Herald (and at least one other Massachusetts team) considered the state championship.10

While most prominent 1850s base ball matches came about as the result of a challenge, this one did not. The Winthrop Club invited Olympic to play them in a match game. As such, Olympic could have declined without risk to their reputation. Their acceptance was reported by the Boston Herald.11

Beautiful weather greeted “an immense concourse” of 2,000 to 3,000 spectators on match day.12 Standing seven or eight deep, the crowd encircled the roped-off playing area, located on the parade ground at the southwest corner of the Boston Common.13 Policemen “stationed at regular intervals” kept the crowd behind the ropes,14 allowing only a few lucky patrons bearing entrance tickets to pass through the barrier and gather on the west side of the enclosure.

Three referees (umpires) officiated the match, including, as MABBP rules specified, one member from each side and another from a third club affiliated with the association. The referee provided by the Olympics was their president, A.S. Frye, who also served as MABBP secretary.15 The third-party referee was a member of the Rough and Ready club of South Walpole.16 A trio of tallymen (scorers) were similarly selected, with the third-party scorer provided by the Union Club of Medway.

Play began at about 2 P.M., with Winthrop “having the first innings” – i.e., batting first.17 No details were provided in newspaper accounts of how runs were earned in the first inning or any other. The Boston Herald, Boston Traveller, and New York Clipper provided batting orders, with the number of runs scored by each player, but did not identify the positions they played or the number of “hands” each lost (outs recorded), information that was commonly, though not always, included with New York-game box scores.18 As a result, its unknown who pitched, who were the base tenders (infielders), and who were the scouts (outfielders).

The three box scores published for the match largely tell the same story, with a few exceptions. The New York Clipper account identified Winthrop’s fourth and sixth strikers as “E.G. Whitney” and “T.M. Whitney,” respectively, while the Boston newspapers claimed the pair’s surname was Whiting.19 The Traveller identified the number-five batter for the Olympics as “B. Crowley,” and the number-nine batter for Winthrop as “B.C. Bigelow.” The other two game accounts listed the pair as “B. Crawley” and “R.C. Bigelow.” In each of these instances, the author has assumed that spellings that match in two of the three publications are the correct ones.

A few players who were (or would be) prominent in the Boston baseball community appeared in the lineup for each side. Batting second for Winthrop was P.R. Johnson, who weeks earlier had been elected MABBP president.20 Olympic club vice president B.F. Rollins played, as did Olympic treasurer G.C. Grimes, director Henry F. Gill, former vice president Harrison Forbush, and former secretary E.T. Allen.21 Batting 10th for Olympic was B.H. Hoyt, who three months later became the first president of the Boston Base Ball club.22 Olympic’s number-four batter, Moses E. Chandler, then in his mid-20s, later served as an umpire in a handful of National Association (1872-1874) and National League (1877) games played in Boston and Hartford, Connecticut.23

Winthrop managed a single tally in the top of the first inning, which Olympic matched in their first turn at bat. Four runs in the second inning gave Winthrop the lead. Olympic was blanked in innings two through five as Winthrop put up a pair of 10-run innings, building a 30-1 lead.

Twenty Winthrop tallies in the 10th, followed by another eight in the 11th gave it 69 runs against a measly 7 for Olympic. More than two-thirds of the way to the 100, the Winthrop offense slowed, while Olympic inched a bit closer. After 22 innings, the Hollistoners led 85-27. Finally, in the 33rd inning, 4½ hours after the game began, Winthrop reached the century mark and won the match. Olympic, which went scoreless over the final 11 innings, “bore their defeat manfully,” according to the Boston Herald.24

High scorers in the match were Winthrop’s number-five and -six hitters, Edward Rockwood and T.M. Whiting, respectively, who each recorded 11 runs. A trio of Olympic batters, George W. Wadsworth, G.B. Stone, and B. Crowley, paced the losing side with 4 runs each.

In one respect, this game was no different than many base ball matches held 200-plus miles to the southwest in New York City. After the competition was over, both sides adjourned to a local hotel where they “partook of a sumptuous repast.”25

Ten months after this game, The Base-Ball Player’s Pocket Companion first became available to the public for the price of 25 cents from Boston publisher Mayhew & Baker. Advertised as “a complete manual of Base Ball,” it “[contained] all matters relating to both Massachusetts and New York Games,” including the rules for each style of play.26

Ten years after this game, on the last Monday in the month of May 1868, Memorial Day was first observed, commemorating the sacrifices of those who died to preserve the Union in the Civil War. One of those was Sergeant E.G. Whiting, Winthrop’s cleanup batter, killed in action during the Battle of Charles City Court House on June 30, 1862.27 By the time Whiting’s ultimate sacrifice was honored nationwide, the New York game had become the dominant style of baseball in New England, making the pages within The Base-Ball Player’s Pocket Companion devoted to the Massachusetts game little more than a curiosity.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Photo credit: New York Clipper, May 29, 1858.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Peter Morris, ed. Base Ball Founders: The Clubs, Players and Cities of the Northeast That Established the Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2013), and John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011). The author reviewed accounts of this and other Massachusetts game matches published between 1855 and 1859 in the New York Clipper, Boston Herald, Boston Traveller, Worcester Spy, and Spirit of the Times. He also examined the Baseball-Almanac.com, Retrosheet.com, and the National Park Service Civil War Soldiers and Sailors system (www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm) websites for pertinent information.

Notes

1 The New York and Brooklyn clubs had settled upon their NABBP sobriquet just weeks earlier, but had codified their rules in early 1857. “Base Ball,” New York Clipper, April 3, 1858: 396; “Rules for Sports and Pastimes: No. II,” New York Clipper, May 2, 1857: 13.

2 “Base Ball Convention in Massachusetts,” New York Clipper, May 29, 1858: 44.

3 “Base Ball Convention,” Spirit of the Times, May 22, 1858: 180.

4 “Base Ball Convention in Massachusetts.”

5 Retiring a baserunner by throwing a ball at him was expressly prohibited in the Knickerbocker rules of 1845, recognized as the first detailed set of rules for the New York game. “Knickerbocker Rules,” Baseball Almanac website, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/rule11.shtml, accessed October 3, 2023.

6 A bound out was a ball caught after one bounce. NABBP rules adopted in 1857 allowed bound outs and continued to do so for several more years. “Rules for Sports and Pastimes: No. II,” New York Clipper, May 2, 1857: 13; John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden, 75.

7 The Worcester Winthrop Club is described as participating in a Whig political rally in 1851, while the Boston Winthrop Club hosted an evening social event for Whigs the following year. The clubs’s namesake was either the house in which they held their first meeting or an early Massachusetts Bay colony governor. “The Winthrop Club,” Boston Globe, March 11, 1874: 8; “The War-Time Park-St. Pastor,” Boston Evening Transcript, January 18, 1892: 4. “Ward Ten,” Boston Evening Transcript, November 6, 1851: 2; Social Entertainment,” Greenfield (Massachusetts) Recorder, May 10, 1852: 3; New York Times, May 24, 1852: 2.

8 Tom Moroney, “Mudville: Name in a Game?” Boston Globe, March 17, 1996: 10-West.

9 Bruce Allardice, “Olympic Club of Boston,” Protoball website, https://protoball.org/Olympic_Club_of_Boston, accessed September 14, 2023.

10 The Union Base Ball Club of Medway referred to Massapoag as the state champion in a match challenge they issued to that club in September of 1857. “An Exciting Game of Base Ball on the Common,” Boston Herald, June 30, 1857: 2; “Challenge,” Boston Herald, September 3, 1857: 2.

11 “Base Ball Match – Olympic vs. Winthrop Club,” Boston Herald, May 29, 1858: 4.

12 “Great Base Ball Match of Boston,” New York Clipper, June 12, 1858: 163.

13 Newspaper reports described the playing area as between one and three acres. “Great Base Ball Match of Boston”; “The Base Ball Match on the Common,” Boston Traveller, June 1, 1858: 2.

14 “The Base Ball Match on the Common.”

15 “Olympic Ball Club,” Boston Evening Transcript, April 8, 1858: 4.

16 The South Walpole club was presumably one of many Rough and Ready social clubs that sprang up across the United States in 1848 to support General Zachary “Rough and Ready” Taylor’s successful bid for the presidency. “Great Base Ball Match of Boston”; The Inauguration of Gen. Zachary Taylor (Philadelphia: Smith & Peters, 1849), https://www.loc.gov/resource/pga.00307/, accessed September 20, 2023.

17 “Base Ball Match on the Common.”

18 See, for example box scores published in “Ball Play,” New York Clipper, May 29, 1858: 43.

19 “Great Base Ball Match of Boston.”

20 “Baseball of the Vintage of 1859,” Boston Globe, October 27, 1912: 49.

21 “Ball Playing,” Boston Herald, April 3, 1857: 2. Forbush’s last name was listed as both “Porbush” and “Furbush” in newspaper listings of club’s officers for 1857. “Olympic Ball Club.” “Ball Playing,” Boston Evening Traveller, May 2, 1857: 5.

22 “Boston Base Ball Club,” Boston Evening Transcript, August 25, 1858: 1.

23 Chandler crossed paths with a pair of early catching pioneers in games he umpired in 1877. On April 15 of that year he worked an exhibition between the National League Boston Red Stockings and Harvard College, whose catcher, Jim Tyng, had days earlier become the first catcher to don a catcher’s mask in competition. In Chandler’s final championship (regular) season game as an NL umpire, on August 21, Cincinnati Reds catcher Scott Hastings, who several weeks before had become the second catcher to wear a mask in a major-league regular season match but then abandoned it, once again donned “the wire mask invented by Thayer of the Harvards.” “Summer Pastimes,” Boston Globe, August 22, 1877: 5; “The Bostons Beat the Harvards, Five to Two,” Boston Globe, April 16, 1877: 1; “General Notes,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, April 17, 1877: 8; Larry DeFillipo, “August 8, 1877: Brown Stockings’ Mike Dorgan becomes first major leaguer to adopt a catcher’s mask,” SABR Games Project.

24 “Base Ball Match on the Common.”

25 “Great Base Ball Match of Boston.”

26 “The Base Ball Players’ Pocket Companion,” New York Clipper, May 21, 1859: 39.

27 “The Sixteenth Massachusetts Regiment,” Boston Evening Transcript, July 14, 1862: 4. Several other members of the Winthrop Club also fought in the War Between the States. Rufus Durfee, Winthrop’s number-eight batter, served alongside E.G. Whiting in the 16th Massachusetts Regiment. Initially reported as missing after the battle in which Whiting was killed, Durfee was later wounded in action on May 3, 1863. The other Whiting in the Winthrop lineup, T.M., spent three years fighting with the 17th Massachusetts. Edward Rockwood, who batted between the two Whitings in this match, may have served in the 57th Massachusetts. An Edward P. Rockwood was gravely injured during a June 1864 battle in Virgina, then “taken prisoner, and starved for several months.” The author has identified several other names in Massachusetts regiment Civil War muster lists that match those of participants in this match: For the Olympics, G.B. Stone (either 13th or 56th Massachusetts), B. Crowley (2nd, 19th, or 28th), M. White (2nd, 3rd, 28th, 31st, or 51st), H. Forbush (44th) and B.H. Hoyt (23rd) and for the Winthrop Club, J.W. Cutler (10th Massachusetts), George Hoffman (11th or 47th) and J. Puffer (5th, 26th, 32nd, 43rd, or 57th). “Seeley’s Battery,” Washington Evening Star, May 13, 1863: 1; “Death of T.M. Whiting,” Indianapolis Star, July 2, 1905: 12; “Couldn’t Kill Him,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Evening News, July 20, 1865: 2.

Additional Stats

Winthrop 100

Olympic 27

Boston Common

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.