The St. Louis Cardinals in Wartime

This article was written by Gregory H. Wolf

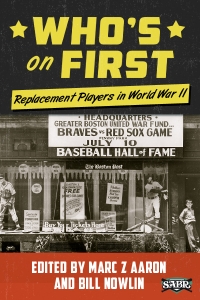

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

The St. Louis Cardinals were the most successful major-league team during America’s involvement in World War II. Manager Billy Southworth led the Redbirds to three consecutive pennants and two World Series championships from 1942 through 1944, and to a second-place finish in 1945. Although they benefited from a remarkable level of continuity, especially among their starters during those first three years, St. Louis also lost its fair share of players to the war effort. But with their unparalleled farm system, the Cardinals were well positioned to adapt to depleted rosters and plug in major-league ready replacements at seemingly every position.

The seeds for the Cardinals’ success during the war years were sown more than a generation earlier. In 1920 Sam Breadon, a self-made millionaire and automobile magnate, bought controlling interest in the club. Soon thereafter general manager Branch Rickey began purchasing minor-league teams and stocking them with players in what became known as the first modern “farm system.” Most importantly, it served as a quick and inexpensive way to develop players, instead of purchasing them from other minor- or major-league teams.

As the Cardinals won pennants in 1926, 1928, 1930, 1931, and 1934, their farm system grew. In 1932 St. Louis controlled 11 teams (and approximately 270 players); by 1940 those figures had grown to 31 teams and in excess of 775 players. That same year only two of the other 15 big-league teams had more than 10 affiliates: the New York Yankees (14) and Brooklyn Dodgers (18). The farm system, which players disparagingly called the “chain gang” and to which Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis was adamantly opposed, provided the Cardinals with a seemingly endless pool of talent. It also infused the club with much-needed cash by enabling Breadon and Rickey to sell or trade superstars at the first sign of slippage, and sell prospects. “It’s better to trade a player a year too early than a year too late,” Rickey was supposedly fond of saying.

By 1940 Breadon and Rickey’s relationship was strained, as much the result of clashing personalities as it was from financial considerations. Attendance for Cardinals games at Sportsman’s Park (where they were tenants of the St. Louis Browns) fell to just over 291,000 in 1938. As Lee Lowenfish explained in his groundbreaking biography of Rickey, Breadon informed the Cardinals board of directors in February 1941 that he would not renew Rickey’s contract when it expired at the end of the 1942 season, citing economic uncertainly and a raging war in Europe.1 A year and half earlier, Germany had invaded Poland, and by the end of May 1940 had occupied much of Western and Northern Europe.

For the most part, Major League Baseball was oblivious to the war in 1941. After all, the United States was officially neutral and not involved in active combat. In May, however, fans, players, and owners got an inkling of that would come: reigning AL MVP Hank Greenberg was drafted and went into the service. Nonetheless, the country was filled with optimism. With the crippling economic depression of the 1930s a receding memory, baseball drew in excess of 9.5 million spectators for the second consecutive season.

After several mediocre seasons in the late 1930s, including a sixth-place finish (71-80) in 1938, the Cardinals finished second and third to the Cincinnati Reds in 1939 and 1940, and were poised to reclaim their stake as the NL’s best club. The following season, the Cardinals battled the Brooklyn Dodgers in one of the best and most celebrated pennant races in league history, only to fall short by 2½ games.

Less than two months after the New York Yankees defeated the Brooklyn Dodgers in the World Series, Japanese warplanes attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7. The following day, the United States declared war on Japan; and on December 11 on Germany, in response to that country’s declaration of war.

The bombings of Pearl Harbor changed America overnight and galvanized a united American response on behalf of the war effort. Essential products and services were rationed, and young, physically fit men were drafted. No doubt baseball owners thought about the effects war would have on the coming baseball season, or if there would even be a season. Owners, players, and fans old enough to remember World War I recalled Provost Marshal General Enoch Crowder’s “Work or Fight” decree from July 1918, requiring all draft-eligible young men in “non-essential” occupations to apply to war-related jobs or risk being drafted. Baseball was considered a “non-essential” occupation. In light of this uncertainly, Commissioner Landis sent President Franklin D. Roosevelt a personal letter asking what baseball should do.

On January 15, 1942, President Roosevelt gave his response in what became known as the “Green Light Letter.” “I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going,” wrote the president. “There will be fewer people unemployed and everybody will work longer hours and harder than ever before. And that means that they ought to have a chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work even more than before.”2

Baseball owners met in early February 1942 to determine how to keep the game “going.” In his thorough study, For the Good of the Country, David Finoli explained that the owners discussed night games, salaries, attendance, admission issues, and the All-Star Game.3 Another topic was Major League Baseball’s financial support of the war. Its response over the next four years was noteworthy. The league and teams donated proceeds to various war-related causes. The World Series, All-Star Games, regularly scheduled relief games between teams, as well as exhibition games between major- and minor-league teams and major-league and military teams, raised tens of millions of dollars for the war.4 The St. Louis Cardinals even sold memorabilia (such as gloves and autographed balls) after their World Series championship in 1942 for well over $100,000 in war bonds.5

Branch Rickey, despite his lame-duck status as GM of the Cardinals, proceeded with business as usual in his final two seasons with the club. The team’s attendance almost doubled from 1940 to just over 633,000 in 1941, aided by the dramatic, season-long pennant race. Preferring speedy, line-drive hitters over home-run sluggers, Rickey traded All-Star first baseman Johnny Mize to the New York Giants for three players and cash in the offseason, just one year after another headline-grabbing trade, when he sent former slugging star Joe Medwick (the NL’s Triple Crown winner in 1937) to the Dodgers in June 1940 for four journeymen players and $125,000.

As the Cardinals arrived in spring training camp in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1942, the atmosphere was markedly different than in years past. In January, Cleveland Indians pitcher Bob Feller had become the first major leaguer to enlist into the service, and many players wondered when they might be drafted. By season’s end, 71 players with big-league experience were in the service.6 In his well-researched study, High-Flying Birds: The 1942 St. Louis Cardinals, Jerome M. Mileur noted that Cardinals players were consumed by newspaper and radio reports about the war, and there was little discussion about unseating the Dodgers.7 Manager Billy Southworth, detecting his players’ anxiety, urged them to show “more enthusiasm.” “Since the president has asked baseball to carry on during the war,” he said. “It is up to us to give fans something to take away from the games.”8 Like many other teams, the Cardinals admitted service men and women in uniform to home games free of charge. Nonetheless, baseball experienced a drop in attendance of about 13.5 percent (to 8.5 million). The Cardinals finished fourth in attendance in the NL (553,552), a decrease of 12.6 percent.

The Cardinals were the NL’s youngest team in 1942. A pair of rookies played major roles on the team: 21-year-old Stan Musial, who had batted over .400 as a late-season call-up the previous season, earned the starting berth in left field on Opening Day; Whitey Kurowski eventually took over third base. Holdovers from the ’41 squad included second baseman Creepy Crespi, shortstop Marty Marion, right fielder Enos Slaughter, and center fielder Terry Moore, who at 30 was the oldest regular on the team. Rounding out the lineup were Walker Cooper, a 27-year-old catcher in his second full season, and jack-of-all trades Johnny Hopp, who replaced Mize at first base.

In second place 10 games behind the Dodgers in August 5, the Cardinals surged over the final two months of the seasons, winning 43 of 51 games to finish at 106-48 and capture the pennant by two games over their archrival from Brooklyn. In establishing a club record for victories, the Cardinals relied on a team effort to lead the NL in many offensive categories, including hitting (.268) and runs scored (755), but did not have a career-defining season from any batter. Slaughter led the squad in home runs (13), RBIs (98), and batting (.318); Musial emerged as a good, though not yet great, player, batting .315. The key to the Cardinals’ pennant was their great pitching staff, whose cumulative ERA (2.55) established a new post-Deadball Era record. The unequivocal ace was righty Mort Cooper, Walker’s brother, who won the MVP Award with a 22-7 record, 1.78 ERA, and 10 shutouts. Rookie Johnny Beazley won 21 games (and two more in the World Series). Five players (the Cooper brothers, Slaughter, Moore, and Jimmy Brown, who had started at third base for the Cardinals in 1941 but split his time between third and second in 1942) were named to the All-Star Game.

The Cardinals defeated the New York Yankees in the World Series in five games. Both teams were relatively unaffected by the war. The Redbirds had lost only two minor role players from the previous season (outfielder Walter Sessi and pitcher Johnny Grodzicki), while the Yankees were without Johnny Sturm, the starting first baseman on their 1941 World Series championship team. According to Lee Lowenfish, with the war raging and players apprehensive about their career, the Cardinals’ celebration in St. Louis after their victory was subdued compared to 1934 when the Gas House Gang defeated the Detroit Tigers.9 The Cardinals title was Rickey’s swan song in the Mound City – by the end of the month he had accepted Brooklyn’s offer to become general manager. Rickey’s footprint, especially the hundreds of players he signed to his farm system, was evident on the Cardinals long after his departure.

As the war raged in the Pacific and European Theaters over the winter of 1942-1943, baseball reiterated its commitment to play another season. “As long as we can put nine men on the field,” said Commissioner Landis at the baseball writers’ annual dinner in New York in February 1943, “the game will not die. Let 60 million baseball fans raise their voice as to whether the game should or should not be played in these times.”10

The visible effects of the war were much more pronounced on baseball in 1943. Joseph B. Eastman, head of the Office of Defense Transportation, requested that baseball address team traveling schedules as a way to conserve valuable resources and energy. Consequently, as David Pietrusza points out in his authoritative biography on Landis, Judge and Jury, the commissioner formulated the “Landis-Eastman-Line” and dictated to the club owners without their approval that teams must conduct spring training north of the Ohio River or east of the Mississippi. The two teams from St. Louis, the Cardinals and Browns, were permitted to train anywhere in Missouri.11 More noticeable to the fans was the loss of even more players to the war. By 1943 the number of big leaguers in the service had tripled, to 219, highlighted by the two biggest names in baseball, Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams.

The Cardinals experienced substantial changes in 1943. William Walsingham, Jr., the nephew of Sam Breadon, succeeded Rickey as GM of the club; however, Breadon remained the real source of power and decision making. The team conducted its spring training from 1943 to 1945 in Cairo, Illinois, about 150 miles southeast of St. Louis. Its farm system was dramatically reduced in size, going from 26 to 22 to seven clubs from 1941 to 1943. They maintained seven clubs with approximately 250 players under contract through 1945. The minor leagues across the United States, as Robert A. Burk points out in his excellent study, Much More Than a Game, were especially hard hit by the war.12 The number of leagues fell precipitously from 44 in 1940 to 10 in 1944. The Cardinals, who had long relied on their farm system to supply them with talent, began conducting tryouts throughout the United States, wrote to baseball coaches all over the country looking for prospects, and published ads in The Sporting News enticing men to try out for any of their minor-league clubs.13

Another major change during the war years could be seen in the stands at Sportsman’s Park. Baseball was under increased pressure to integrate, given that African Americans were being called to fight for Uncle Sam, yet were not permitted to play in Organized Baseball. The Cardinals and the Browns finally relented to this pressure and became the last teams to eliminate segregated seating in their home park.14

As the Cardinals prepared to defend their World Series title in 1943, they were without three of their most important starters – Enos Slaughter, Terry Moore, and Johnny Beazley – who were in the service. Joining them in the war effort was another starter, Creepy Crespi, as well as utilitymen Jeff Cross and Erv Dusak, and pitcher Whitey Moore. The team had four new starters: Ray Sanders at first base and rookie Lou Klein at second base; and outfielders 26-year-old Harry Walker and Danny Litwhiler (an All-Star with the Philadelphia Phillies the year before who was acquired on June 1 in a multiplayer trade). Crespi’s fate was especially unkind. He suffered a compound fracture of his left leg while playing a game for the Army in 1943, and broke the same leg later that year in a training maneuver when his tank overturned. While recuperating, he fractured the leg for the third time in an impromptu wheelchair race.15 When a nurse incorrectly applied a dosage of boric acid to his bandages, he suffered severe burns and was left with a permanent limp, thus ending his baseball career.

After two dramatic pennant races with the Dodgers, the Cardinals rolled like a Sherman tank through the 1943 regular season. By the end of July, they enjoyed a double-digit lead over the Pittsburgh Pirates and Dodgers, and finished the season with a 105-49 record, 18 games in front of the Cincinnati Reds. Despite the team’s success, attendance at Sportsman’s Park dropped about 6.5 percent to just over 517,000 (third best in the league); however, overall attendance at major-league parks fell a staggering 12.7 percent to a level it had not seen since the Great Depression, in 1935. Because of the shortage of rubber, Major League Baseball introduced a new ball, the “balata ball,” in 1943. Players complained that the new ball was dead, and power numbers continued to decline.16 Home runs decreased from 1,071 to 905 and runs dropped by about 3 percent, to 9,687. The Cardinals led the NL in numerous offensive categories, including hitting (.279), and were second in home runs (70) and runs scored (679). Musial, just 22 years old, emerged as the best young talent, perhaps the best player regardless of age, in the NL, leading the league in hitting (.357) and slugging (.562), while tying for the team lead in homers (13) and RBIs (81), and earning the NL MVP.

As good as the Cardinals’ offense was, their pitching was even better, leading the majors with a 2.57 ERA. Staff ace Mort Cooper tied for the NL lead in wins (21) and southpaw Max Lanier won 15 games and topped the circuit with a 1.90 ERA. Their best pitcher may have been Howie Pollet who went 8-4 (1.75 ERA) with five shutouts before he enlisted in the Army Air Corps in July.

A spectator at the 1943 All-Star Game in Philadelphia’s Shibe Park might have mistaken it for a Cardinals game. Five of the nine starters were Redbirds: the Cooper brothers repeated from the previous year, while Marion, Musial, and Walker played in their first game. Substitutes included Kurowski, Lanier, and Pollet.

In a rematch of the previous World Series, the Cardinals lost in five games to the New York Yankees, whose slugging stars DiMaggio and Tommy Henrich were in the service. The first three games took place at Yankee Stadium in accordance with the new 3-4 scheduling format to reduce wartime travel. In a tightly-pitched series (featuring just 26 total runs), the Yankees’ 35-year-old hurler Spud Chandler was the difference maker, tossing two complete-game victories.

The Cardinals ran roughshod over their competition again in 1944, winning 105 games and capturing their third consecutive pennant, by 14½ games over the Pittsburgh Pirates. As Robert F. Burk has demonstrated, major-league rosters were barely recognizable from three years earlier. By 1944 the number of big leaguers in the service had increased to 470; 60 percent of the starters from 1941 were in the military; and 30 All-Stars from 1942 and 1943 were fulfilling military commitments.17 An increasing number of younger, inexperienced, or older players (“Greybeards”) populated rosters, as did players with 4-F designations (physically unfit to serve in the military). Teams averaged 10 4-F players in 1944; by 1945 it had grown to 16.18

There were some positive signs in baseball in 1944. Most significant was a dramatic, 17.5 percent increase in attendance to more than 8.7 million. Offensively, baseball enjoyed a 14.3 percent spike in home runs and an almost 7 percent increase in runs scored. The Cardinals, however, experienced a 10 percent drop in attendance, drawing just 461,968 to Sportsman’s Park. While Major League Baseball canceled the two scheduled games on June 6 when America and its allies launched D-Day and landed on the beaches of Normandy in northern France, the Cardinals played an exhibition game against the Wilmington (Delaware) Blue Rocks, the Philadelphia Phillies affiliate in the Class-B Interstate League.19 The following month at the All-Star Game in Pittsburgh, baseball donated all receipts to a fund that purchased baseball equipment for service teams.20

In the context of a fluctuating baseball landscape, St. Louis benefited from continuity among their starting position players from 1943 to 1944. And for the third consecutive season, the Cardinals were the youngest team in baseball.21 Back were Sanders, Marion, and Kurowski in the infield, Musial and Litwhiler in the outfield, and Cooper behind the plate. The biggest loss was All-Star flychaser Harry Walker, whose position Johnny Hopp took. The war gave an opportunity to 28-year-old rookie Emil Verban, who after toiling in the minors since 1936, took over for the departed Lou Klein at second base. The Cardinals also lost role players Jimmy Brown, Earl Naylor, and Johnny Wyrostek (acquired in an offseason trade with the Pittsburgh Pirates in exchange for pitcher Preacher Roe), paving the way for the return of one of the most beloved players in Cardinals history. The 40-year-old Pepper Martin, who had served as a player-manager in the minors the previous three seasons, returned to play in 40 games.

Given the club’s stability, it is no wonder that the Redbirds once again featured the NL’s most productive offense. They led the league in most offensive categories, including hitting (.275), slugging (.402), home runs (100), and runs (772). A well-balanced team, they boasted three .300 hitters, led by Musial (.347), Hopp (.336), and Cooper (.317); Kurowski topped the team with 20 round-trippers. Ray Sanders is arguably the Cardinals’ best example of a wartime “star.” He started at first base from 1943 to 1945 and led the team with 102 RBIs in 1944. He was sold to the Boston Braves in spring training of 1946, and played in only 94 more games before he was out of the majors after the 1949 season.

Like their offensive counterparts, the Cardinals pitching staff was once again the best in baseball, handily leading the majors in ERA (2.67) for the third consecutive season. Mort Cooper (22 wins) and Max Lanier (17) were joined by two major contributors whose careers got a boost from depleted rosters. Harry Brecheen, a 29-year-old southpaw in his second full season, won 16 games; Ted Wilks, a 28-year-old rookie, burst on the scene by going 17-4. But the Cardinals also lost their share of hurlers. They included swingman Howie Krist, who had gone 34-8 from 1941-1943; Al Brazle, Ernie White, and Murry Dickson. The staff’s most important loss was hard-throwing George “Red” Munger, who posted a stellar 11-3 record and 1.34 ERA before he was called to the service at the All-Star break.

Six Cardinals were named to the All-Star team. Musial, Marion, and Walker Cooper repeated as starters. Kuroswki and Lanier joined the squad for the second consecutive summer, and Munger was selected, but had already reported for his mustering-in at Jefferson Barracks, outside of St. Louis.

The unexpectedly competitive “Trolley World Series” pitted the Cardinals against their landlords, the Browns, traditional doormats of the AL who captured their first and only pennant that season. Pitching was the story of the series with just 28 runs scored cumulatively in six games. The Browns took two of the first three games before the Cardinals won the final three. The Redbirds were propelled by Brecheen’s efficient complete game in Game Four, Mort Cooper’s seven-hit shutout with 12 strikeouts in Game Five, and a combined three-hitter by Lanier and Wilks in Game Six to capture their second title in three years.

One cannot say with certainty that any given player landed a spot on a big-league roster solely because of the depleted rosters during the war years. But the Cardinals, like all big-league teams, saw the debuts of players whose careers seem unlikely had the war not given them chance to play. In 1944 Bob Keely, a 34-year-old catcher, was signed off the sandlots and played in just two games in the next two seasons but parlayed that experience into a 50-year career in baseball as a respected coach and scout. After nine years in the minors, 30-year-old swingman Blix Donnelly got his chance as a reliever in 1944 and remained in the majors until 1951. Augie Bergamo, a 27-year-old slap-hitting right fielder, batted .304 in 174 games for the Redbirds in 1944 and 1945, but was out of the majors the following year.

The 1945 squad contained a number of players whose big-league careers were confined to that one season, or who made an unexpected return to the big stage for a swan song. Pitcher Jack Creel got a chance after seven years in the minors and won five games; catcher Gene Crumling was a September call-up who managed one hit and knocked in a run; Art Rebel, a 31-year-old outfielder who had last played in the majors in 1938, batted .347 (25-for-72); and a 37-year-old infielder, graybeard Pep Young, was back in a big-league uniform after a four-year absence. On the other hand, the Cardinals roster during the war years contained no player 20 years or younger, let alone teenagers, like several teams, most notably the Dodgers and Phillies, both of which had three teens see action for them in 1945.

In just over a year after the Cardinals celebrated their World Series title over the Browns, Dodgers GM Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson on October 23, 1945, paving the way for the integration of baseball. A month later, on November 25, that path became clearer when Commissioner Landis, whose objections to integration were well known, died. The Cardinals owner, Sam Breadon, along with three others (the Cubs’ Philip K. Wrigley, Cleveland’s Alva Bradley, and the St. Louis Browns’ Don Barnes) were appointed to a committee to determine a slate of candidates for his replacement. Kentucky Senator Happy Chandler, an outspoken supporter of baseball’s morale-boosting qualities, was named baseball commissioner.

As the Cardinals prepared for their third spring training in Cairo, Illinois, the mood was dour in camp. Army Air Force pilot and former minor-league outfielder Billy Southworth, Jr. had been killed just weeks earlier when his Boeing B-29 Superfortress crashed on February 15 in Flushing Bay, New York, during a training flight. While dealing with the tragic loss of his son, the Cardinals skipper also faced major challenges to his championship team. In January, Musial had enlisted in the Navy and would ultimately miss the entire season. Another outfielder, Danny Litwhiler, previously classified 4-F because of a bad knee, was drafted. At least 509 major leaguers were in the service by 1945.

A week before Opening Day in 1945, brothers Mort and Walker Cooper engaged in a “strike” against club owner Sam Breadon for his penny-pinching ways, and threatened to boycott the team’s season-opening series in Chicago. Mort had signed a contract in the offseason paying a reported $12,000 only after Breadon told him the team was limited by the federal Wage Stabilization Act of 1943, which prohibited teams from paying any player more than their highest paid player earned in 1942. For the Cardinals that was Terry Moore’s $12,000 salary. Cooper learned near the end of spring training that Marty Marion had received an exception, and he left camp. But the brothers capitulated and were with the team on Opening Day. Walker was inducted into the US Navy in late April (and later sold in January 1946). The club lost ace southpaw Max Lanier, who was inducted into the service on May 24. A day earlier, the Cardinals traded Mort Cooper to the Boston Braves for pitcher Red Barrett and $60,000.

The Cardinals had major contributions from several new players in 1945. Red Schoendienst, a 22-year-old rookie, took over left field and led the NL with 26 stolen bases. Outfielder Buster Adams, acquired in an early May trade with the Philadelphia Phillies, slugged 20 home runs and drove in 101 runs. The Cardinals’ seemingly endless stream of pitchers kept flowing. Ken Burkhart, a 28-year-old rookie, won 18 games, and the newly acquired Barrett notched 21 wins. But these performances were not enough to compensate for the losses of the league’s best hitter (Musial), best catcher (Walker Cooper), and best pitcher (Mort Cooper). The Redbirds stayed within striking distance the entire season, but ultimately finished in second place, three games behind the Chicago Cubs.

The All-Star Game scheduled for Fenway Park in Boston was canceled. The Associated Press selected unofficial rosters for the AL and NL based on nominations requested from all 16 managers. Billy Southworth was one of three managers who did not participate. Selected to the NL squad were Kurowski, Marion, and Emil Verban. Two additional players, catcher Ken O’Dea and hurler Barrett, were also selected for the first and only time in their careers.

As the war came to a close in Europe with Germany’s capitulation in May and in the Pacific with Japan’s surrender on September 2 only after atomic bombs had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August, fans flocked to stadiums across the US in 1945. Attendance was up an astonishing 23.6 percent to more than 10.8 million, breaking the record set 15 years earlier. Attendance at Cardinals home games shot up 28.7 percent to 594,630 which ranked fifth in the league, on par with Pittsburgh, but well behind Brooklyn, New York, and Chicago, all of whom drew in excess of one million.

Baseball entered a golden age in 1946 as players returned en masse to their teams. Attendance skyrocketed by more than 70 percent to more than 18 million. Led by the New York Yankees (2,265,512), 10 big-league teams drew at least one million, a mark that had been reached only 10 total times since 1931. The Cardinals set an attendance record with 1,061,807.

The year 1946 is often described as a return to normalcy; however, there was nothing normal about the Cardinals as they opened spring training in St. Petersburg in 1946. Gone was skipper Billy Southworth, hired by the Boston Braves. He was replaced by Eddie Dyer, a respected manager in the Cardinals farm system. The Redbirds faced a serious conundrum: too many major-league quality players. The club welcomed the return of former All-Stars Musial, Slaughter, Walker, and Moore, among other players. The competition for spots on the pitching staff proved to be especially intense. Returning were Beazley, Brazle, Dickson, Krist, Lanier, Munger, Pollet, and White. Since the Cooper brothers’ public contract squabble with Breadon the previous year, an uneasy and, indeed, antagonistic feeling toward team ownership permeated the clubhouse, and only intensified in spring training. With federal wage controls no longer in effect, players wanted to cash in on baseball’s newfound prosperity. Unrest reached its apex when Lanier, Fred Schmidt, and Lou Klein in late May accepted an offer from Jorge Pasquel, president of the Mexican League, to jump to his league with promises of exorbitant salaries. Pasquel was unsuccessful in his attempt to lure other Cardinals, such as Musial and Slaughter. Commissioner Chandler summarily suspended all “Mexican jumpers” from Organized Baseball for five years. When Chandler discovered that Breadon planned to travel secretly to Mexico to encourage his players to return, the commissioner fined the owner $5,000 and suspended him for 30 days.22

Normal, however, could be used to describe the Cardinals’ performance on the diamond in 1946. Propelled by league MVP Musial, the Redbirds captured their fourth pennant in five years. Along the way, they led the league in hitting for the fifth time in six years, finished in the top two in scoring for the 14th consecutive season, and led the major leagues in ERA for the fourth time in five years. That fall, the Cardinals defeated the Boston Red Sox in seven games to capture their sixth title in 21 years.

A lifelong Pirates fan, GREGORY H. WOLF was born in Pittsburgh, but now resides in the Chicagoland area with his wife, Margaret, and daughter, Gabriela. A Professor of German and holder of the Dennis and Jean Bauman endowed chair of the Humanities at North Central College in Naperville, Illinois, he recently served as editor of the SABR book, Thar’s Joy in Braveland. The 1957 Milwaukee Braves (April 2014) and is currently editing a SABR book on the 1929 Chicago Cubs.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author consulted:

Baseball-Reference.com

Chicago Daily Tribune

New York Times

Retrosheet.org

SABR.org

The Sporting News

Notes

1 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey. Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 309.

2 Gerald Bazer and Steven Culbertson, “When FDR Said ‘Play Ball,’ ” Prologue Magazine, Spring 2002, Vol. 34, No. 1. The National Archives. archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/spring/greenlight.html.

3 David Finoli, For the Good of the Country. World War II Baseball in the Major and Minor Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002), 11.

4 Steven R. Bullock, Playing for Their Nation. Baseball and he American Military During World War II (Lincoln Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 35.

5 Bullock, 36.

6 Finoli, 59.

7 Jerome M. Mileur, High-Flying Birds: The 1942 St. Louis Cardinals (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2009), 26.

8 Mileur, 24.

9 Lowenfish, 317.

10 Finoli, 54.

11 David Pietrusza, Judge And Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1998), 434.

12 Robert F. Burk, Much More Than a Game. Players, Owners & American Baseball Since 1921(Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 72.

13 Burk 71, and Finoli 108.

14 John David Cash, “The St. Louis Cardinals,” in Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball, Steven A. Riess, editor.

15 Brian McKenna, Early Exits: The Premature Ending of Baseball Careers (New York: Scarecrow Press, 2007), 97.

16 The dead balls were caused by balata, a substance used in place of war-rationed rubber. The balata hardened and caused the ball not to travel as far.

17 Burk, 71.

18 Burk, 72.

19 Associated Press, “Cardinals Win Over Rocks, 4-1,” The Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland), June 7, 1944, 6.

20 “All Reserved Seats Sold For All-Star Game Here,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 8, 1944, 8.

21 St. Louis had the lowest average age for batters and pitchers in the NL in 1943 (26.5 and 27.6 years) and again in 1944 (27.5 and 28.1); in 1945 they had the lowest average age for batters and the third lowest for pitchers in the NL. In 1942 they had the lowest average in the NL for batters and the third lowest for pitchers.

22 Burk, 86.