Willie Mays Had a Spectacular—But Short—Stay in Minneapolis

This article was written by Stew Thornley

This article was published in Willie Mays: Five Tools (2023)

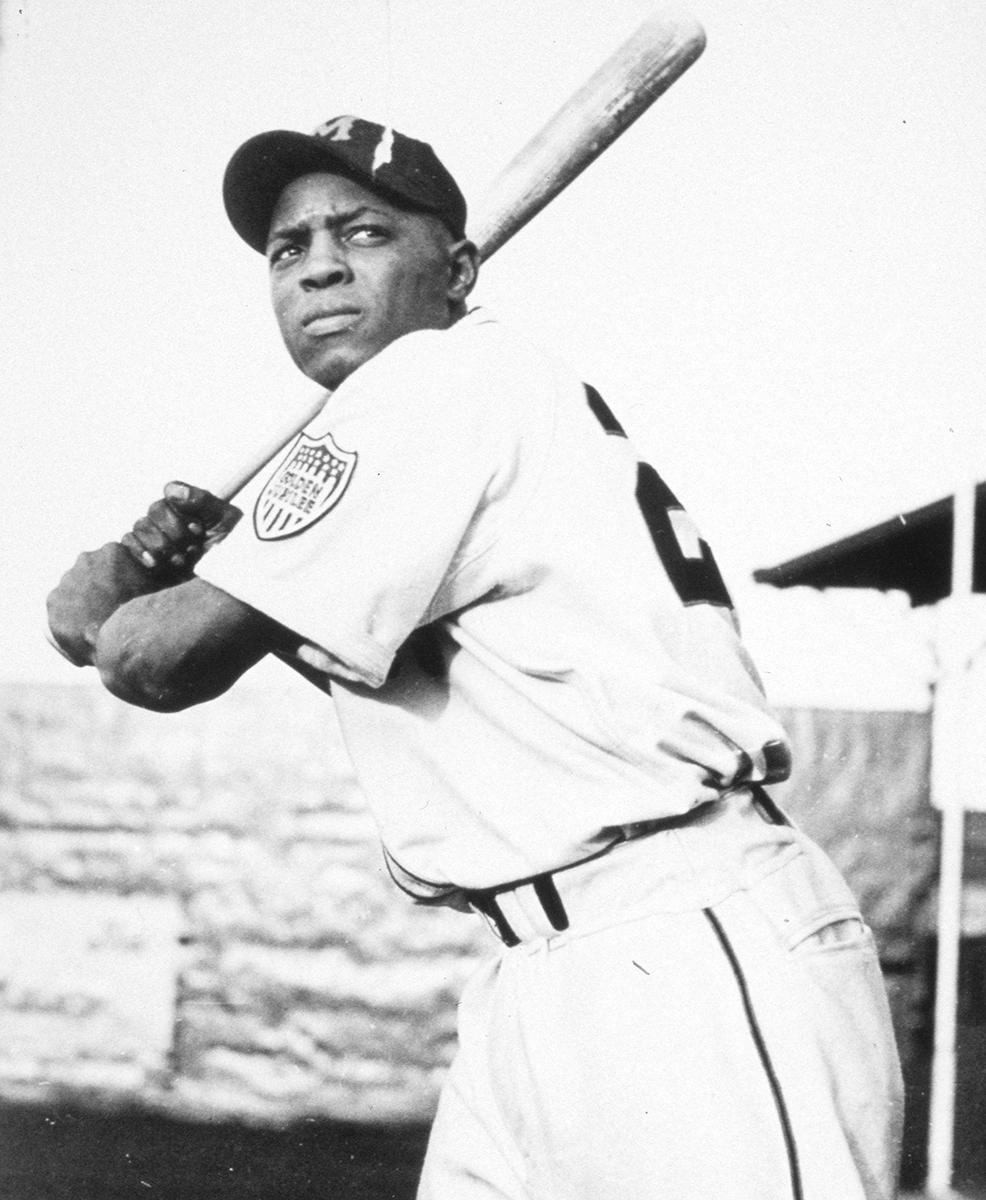

Willie Mays with the Minneapolis Millers in 1951. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

The New York Giants purchased the Minneapolis Millers in 1946. It took five years for Minneapolis fans to fully process the impact.

A charter member of the American Association in 1902, the Millers had a rich history that extended to the final decades of the nineteenth century. The locals had the chance to cheer on many players at cozy and quaint Nicollet Park who ended up in the Hall of Fame. Some were on their way up, such as Roger Bresnahan and Red Faber, although more were veterans who had already established their credentials in the majors, including Rube Waddell and Zack Wheat. Such was the nature of the minor leagues then, prospects combined with those hanging on as long as their talents could earn them a living.

However, the stalwarts were those who never reached such lofty levels but returned year after year – Henri Rondeau, Joe Hauser, Spencer Harris – and were familiar stars to loyalists.

Mike Kelley had operated the Millers since 19241 before being one of the last of the independent owners to turn his operation over to a major-league team. The Millers had had loose affiliations in the past, such as with the Boston Red Sox in 1937-38. However, the team was not fully stocked with players under the control of a parent team. The relationship did give Minneapolis fans the chance to see Ted Williams, who spent a season with the Millers in 1938 and won the league triple crown.

But the 1946 sale was a break toward the Millers being a team used for player development rather than an entity in their own right.2 The fans got an inkling of what was to come with Harold “Tookie” Gilbert. After signing as a 17-year-old with the Giants, he was assigned to the Millers in 1947, too high a level as it turned out. Gilbert did better at lower levels and was back in Minneapolis in 1950. After only six games, the Giants brought him up to the majors, which again proved too much for him. Minneapolis writers used Gilbert as a cautionary tale against rushing a talented prospect too fast, and Gilbert also served as a warning to fans – even if they didn’t yet realize it – that life as a farm team would be different.

Willie Mays, on the other hand, began playing professional baseball while still in high school. He was proving himself on the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League. After Mays graduated from Fairfield Industrial High School in 1950, the New York Giants signed him and sent the young star to Trenton, their farm team in the Class-B Interstate League, in 1950.3 Clearly ready for more, New York placed him with Minneapolis, one of their top farm teams, in 1951.

The Giants had two Triple-A teams in 1951, the Millers and the Ottawa Giants in the International League. The Giants had abandoned Jersey City as a Triple-A team after the 1950 season and kept one of their farm teams in Ottawa in 1951. It was the last year the Giants had two Triple-A teams. SABR members Charlie Bevis and Mark Davis provided insight into why Mays went to Minneapolis rather than Ottawa – that the Giants lacked a commitment to the Ottawa team, having it play on a makeshift diamond within Lansdowne Park, which was the home of the Ottawa team in the Canadian Football League – and that Minneapolis seemed a natural pick over Ottawa for a prospect of Mays’ stature.4

The Giants were committed to Mays, even keeping him from playing winter ball in Cuba.5 Whether it was fear of injury or some other reason for keeping Mays out of winter ball,6 the Giants clearly thought he was ready to perform at the highest level of the minor leagues.

It didn’t take long for others to concur.

As their homestead was being pummeled by mid-March snowstorms,7 the Millers gathered in sunny Sanford, Florida, and opened their exhibition season with a split of games with the Ottawa Giants. Mays homered in one of the games and knocked himself out crashing into the outfield fence in the other. The next day, Halsey Hall provided the first reports on Mays in the Minneapolis Tribune: “You watch him run and throw and hit and you are on his side in a minute, although nobody has thrown many curve balls at him yet and he’s still a green pea in the organized realm. … Willie is lithe, beautifully muscled, just under six feet, weighs 170 pounds and doesn’t vary five pounds in his weight off and in season. Righthanded all the way, he has great power to right center and here the dear old memory of Nicollet’s fences in that direction come back.”8

As the Millers won 13 of 19 spring-training games, Mays led the way with a .408 batting average, 5 home runs, and 29 runs batted in. Minneapolis opened the regular season with a circuit through Columbus, Toledo, Louisville, and Indianapolis. Mays hit .352 in those 13 games.

“Any worry about Willie Mays has just about evaporated,” wrote Halsey Hall as the Millers prepared for their home opener. “He has made a swing through the East now, has faced all kinds of pitching, has been held hitless in only one game. … His throwing for power has lived up to reputation. … His throws are not ‘arches.’ Rather, they are power-laden, even when he throws to put the ball into the hands of a receiver on the ground.

“We think you’ll like Willie.”9

For a time, it had appeared that Minneapolis’s Nicollet Park would be a relic of the past by 1951. It was still a relic – but one with a few years left in it.

In late 1948 the Minneapolis Baseball and Athletic Association (essentially the New York Giants) bought land just west of the Minneapolis city limits and announced plans for a new ballpark for the Millers. The Giants said they hoped to have an 18,000-seat stadium ready by 1950.10 For some reason, a new ballpark on the site never happened. A common perception is that a moratorium on building sports facilities during the Korean War was the reason. However, it doesn’t explain why construction (which likely would have been allowed to continue) hadn’t started by the time the National Production Authority issued its moratorium nearly two years later.11

Whatever the reason, the Millers were still at Nicollet Park. Beyond the inviting nature of Nicollet’s fences, referred to by Halsey Hall in a preceding paragraph, its location off Lake Street and Nicollet Avenue provided a convenient locale for Willie and other players to live.

Willie rented a room at 3616 4th Avenue, within walking distance of the ballpark. Across the street from Mays lived two other Black players on the Millers, Ray Dandridge and Dave Barnhill.12 Andy Sturdevant, then a columnist for MinnPost, wrote that the players were “living in one of the centers of black life in the Twin Cities in the 1950s. The neighborhood’s business and residential district was located around 38th Street and extended north and south several blocks. Forty-Second Street was the boundary ‘– the neighborhood to the north of 42nd Street had one of the highest percentages of black residents in the city,’ according to one study by the city, with the neighborhood to the south almost entirely white. It was one of a few areas in the Twin Cities where African Americans owned their own houses in the postwar boom years, when the Twin Cities’ black population grew by 60 percent. … In the early 1950s, the neighborhood was home to a large number of black-owned shops, banks, groceries, community centers and churches.”13

The weather in early May wasn’t conducive to baseball, but nearly 6,500 fans showed up for the home opener, a Millers victory stopped by rain and poor field conditions in the last of the seventh. “Willie Mays said howdy do as bombastically as any newcomer in history,” wrote Hall. “He got three hits, made a sparkling catch against the flagpole, unfurled a typical throw.”14

A week later Mays made an incredible catch of a drive hit by Louisville’s Taft Wright. “Willie Mays turned scoreboard boy,” wrote Hall. “In the third inning the young genius looked like he was hanging up numbers as he leaped almost to the level of the big league board for a fly ball, banged into the wall and doubled a runner at second base. It will rank as one of the greatest catches you will ever see.”15

Meanwhile, Wright put his head down and hustled into second base, assuming he had a stand-up double, and was incredulous when the umpire informed him he was out. Wright remained at second until manager Pinky Higgins came out and told him that Willie indeed had caught the ball.16

Not many people saw the catch by Mays; attendance for the game was 1,351. In the nearly three weeks the Millers were home, the average attendance was under 2,700. Unpleasant weather kept the crowds down, and many fans planned to see the new phenom when temperatures warmed up. They were in for a surprise.

Throughout the homestand, Mays thrilled those who braved the cold with his bat and his glove in addition to the excitement he generated on the basepaths. He kept it up when the Millers departed for games in Milwaukee and Kansas City. With another two hits on May 23, Mays had a batting average of .477 with 8 home runs, 38 runs, and 30 RBIs in 35 games. It was too much for the parent club to ignore.

The next day, the Giants decided it was time to promote Mays. The Millers were in Sioux City for an exhibition game when Willie got the word. Mays said that Giants manager Leo Durocher had seen him during spring training and told him he would be up later in the year. “I didn’t expect to come up that quickly,” Mays said, “and I didn’t want to come up.”17

Mays was comfortable with how he was playing with the Millers and fearful of how he would do in the majors. He started slowly with New York; he was hitless in his first three games before homering off Boston’s Warren Spahn in the next one. Another drought followed, and his batting average slipped to .0476 (compared with .477 with the Millers), and dropped a bit more before he turned it around. He hit .274 with 68 RBIs in 121 major-league games. Mays received the National League Rookie of the Year Award in 1951 and played 23 seasons in the majors, the greatest baseball player ever in the opinion of many.

Mays wasn’t the first, but to that point he was the most significant, player to be plucked in midseason by the parent club.18 Giants President Horace Stoneham tried to mollify the Millers fans with a quarter-page letter – which appeared beneath ads for United Sewing Service, Farmer Jones Store, and Knaeble’s Home Furnishers and Funeral Directors – in that Sunday’s Minneapolis Tribune. “We appreciate his worth to the Millers, but in all fairness Mays himself must be a factor in these considerations. Merit must be recognized. … Mays is entitled to his promotion, and the chance to prove that he can play major league baseball.”19

Stoneham’s message struck a positive chord with the Tribune, which printed an editorial three days later that read, in part, “… we have not witnessed such a tender observance of the amenities since Alphonse first bowed to Gaston in the comic strips. Stoneham thought that the Mays incident deserved an explanation, and so he explained it in poignant phrases calculated to thaw the coldest fury of the Miller baseball fan. … Give credit to Horace Stoneham – he was gentleman enough to spread a little epistolary balm and ointment on the wounds opened up by Willie Mays’ departure.”20

Whatever balm the fans felt, it was not epistolary, and reporters shared the cynicism. After a call-up of another player (Hank Thompson) by the Giants later in the season, Halsey Hall wrote, “Let [Millers general manager] Rosy Ryan and [manager] Tommy Heath have the gold removed from their teeth and send it to the New York front office. They’ll get it sooner or later anyway.”21

Dick Cullum echoed Hall’s sentiments and starkly spelled out what minor-league baseball had become:

“Baseball on the Triple-A farm is mere exhibition training and is not being conducted with an earnest effort to win games.”22

Mays made a few more playing appearances in Minnesota, in exhibition games at Nicollet Park and Metropolitan Stadium, which became the Millers’ home in 1956. He also played for the National League, in the 1965 All-Star Game. Mays returned for one last exhibition game, against the Twins in 1971, in which he played an inning in center field and one inning at each infield position.23

One of the largest crowds of the season came to the Met for that exhibition game. As a pair of 16-year-old cousins waited for the gates to open, one spotted an older man who appeared to have the same look of anticipation as the teenagers. One of the younger fans thought about asking the man if he had seen Willie play for the Millers. I’m still sorry I didn’t.

STEW THORNLEY joined SABR in 1979 and became motivated to do research and writing. He began researching the history of the Minneapolis Millers, whom Willie Mays played for in 1951, and in 1988 had his first book published, On to Nicollet: The Glory and Fame of the Minneapolis Millers.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Charlie Bevis, Mark Davis, Rod Nelson, Gary Fink, Richard Musterer, and Steve Gietschier among others for providing interesting and valuable information in response to the many queries I had on SABR-L, the SABR listserv.

NOTES

1 Kelley had been a player-manager with the St. Paul Saints in the early years of the American Association. He left St. Paul to become manager of the Minneapolis Millers in 1906 and was suspended by the league after twice attacking the integrity of umpires. He was eventually reinstated and spent many more years with St. Paul before returning to Minneapolis in 1924.

2 In a final act of independence (or perhaps defiance), Kelley acted on one final brainstorm that produced a record crowd for Nicollet Park. Moving up a game with the Saints from later in the season to create a Sunday doubleheader on April 28, 1946, Kelley then ordered the ushers not to close the gates and to let all who desired to see the game in. The result was a paid attendance of 15,761, with 5,000 of those fans on the field, some within 10 feet of the baselines. Special ground rules had to be implemented and all balls hit into the crowd were ruled doubles. The Millers and Saints ended up with 24 doubles in the twin bill as the Saints swept the doubleheader.

3 James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend (New York: Scribner, 2010), 65. Hirsch said Mays went to Trenton in a Class-B league although the Giants would have preferred one of their Class-A affiliates. However, Hirsch says one of the affiliates was in the Southern Association, which included Birmingham. “The Giants weren’t about to send their prize recruit into the heart of the Old Confederacy,” Hirsch wrote. The other Class-A team was in Sioux City, Iowa, but “Racial tensions had been simmering there since an American Indian had been buried in a cemetery for whites, and the Giants feared the arrival of a black baseball player could plunge that town into turmoil.” Note: The Giants did not have a farm team in the Southern Association in 1950; their other Class-A club was in Jacksonville, Florida, in the South Atlantic League. Both the South Atlantic League and Southern Association had a number of teams in the Deep South. Not only that, the South Atlantic League did not integrate until 1953, the Southern Association not until 1954 and then only briefly. For more, see John Thorn’s Baseball Integration Timeline, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/baseball-integration-timeline-b289bc04ca12.

4 Input from SABR members Charlie Bevis and Mark Davis provided insight on why the Giants sent Mays to Minneapolis rather than Ottawa. Email correspondence in July 2022.

5 “Willie Miranda, Nat Rookie, Sparkles in Cuban League,” The Sporting News, February 14, 1951: 25. The Almendares club in the Cuban League had sought to sign Mays after losing another outfielder, Dick Williams, to the military, but the New York Giants refused.

6 After establishing himself with the Giants, Mays played in the Puerto Rican League, forming an eminent outfield with Roberto Clemente and Bob Thurman on a Santurce Cangrejeros team that won the Caribbean Series in 1954-1955.

7 A Minnesota adage was to not take off snow tires until after the boys’ high-school basketball tournament, which seemed to be accompanied by heavy snow each year. In 1951 the storms hit before and after the tournament and even caused a sizable section of Williams Arena, site of the tournament, to collapse a few days before the tournament.

8 Halsey Hall, “19-Year-Old Miller in Fifth Year of Baseball,” Minneapolis Tribune, March 20, 1951: 15.

9 Halsey Hall, “It’s a Fact,” Minneapolis Tribune, May 1, 1951: 18.

10 Halsey Hall, “New Ball Park Deal Closed,” Minneapolis Tribune, December 13, 1948: 1.

11 The Minneapolis Park Board got permission to continue construction of football and baseball stadiums on the Parade Grounds on the edge of downtown Minneapolis despite the NPA moratorium, an indication that the Giants could have finished any baseball stadium it had started by that time. The Giants originally seemed intent on having a stadium finished by 1950 at the latest, and regular updates on the ballpark appeared in the St. Louis Park newspaper through 1949 before mysteriously disappearing in early 1950. The Giants, who had bought the land from a neighboring restaurant, held the property into the 1970s. The restaurant, which had reportedly sold the land at a discount, banking on a ballpark bringing in more customers, unsuccessfully sued the Giants based on an agreement the restaurant claimed it had with the Giants to be able to buy back the land if there was no ballpark on it within five years.

12 Rolf Felstad, “Such a One Is Willie,” Minneapolis Tribune, Sunday, May 27, 1951: 3F.

13 Andy Sturdevant, “Willie Mays’ South Minneapolis Neighborhood,” MinnPost, October 12, 2016, https://www.minnpost.com/stroll/2016/10/willie-mays-south-minneapolis-neighborhood-just-two-months-1951.

14 Halsey Hall, “Millers ‘Mudders’ Overwhelm Columbus 11-0,” Minneapolis Tribune, May 2, 1951: 19.

15 Halsey Hall, “Millers Beat Colonels 10-9,” Minneapolis Tribune, May 8, 1951: 21.

16 Rob Tanenbaum, “Minneapolis Ignored Mays,” Minneapolis Star, January 23, 1979: 3D.

17 Author interview with Willie Mays, July 9, 2002.

18 Ottawa fans were experiencing the same bruised feelings as those in Minneapolis. When the Giants called up Mays, they sent shortstop Artie Wilson, who had been a star with Birmingham in the Negro American League, to Ottawa. When the Millers had an injury to infielder Rudy Rufer, the Giants then transferred Wilson to the Millers to fill the gap. Joe Hendrickson, “Sports Views,” Minneapolis Tribune, June 6, 1951: 20.

19 Minneapolis Tribune, May 27, 1951: 4E.

20 “That Stoneham Letter,” Minneapolis Tribune, May 30, 1951: 6.

21 Halsey Hall, “It’s a Fact,” Minneapolis Tribune, August 31, 1951: 19.

22 Dick Cullum, “Cullum’s Column,” Minneapolis Tribune, August 30, 1951: 18.

23 For the Giants, Mays played in exhibition games in Minnesota against the Millers on August 11, 1954; June 23, 1955; June 7, 1956; June 17, 1957; and June 15, 1959. He played in an exhibition game against the Chicago White Sox on May 19, 1958, and against the Minnesota Twins on August 9, 1971. He also played for the National League in the All-Star Game in Minnesota on July 13, 1965. In eight games, he had a batting average of .455 with five home runs and seven runs batted in.