‘We Were the Only Girls to Play at Yankee Stadium’

This article was written by Tim Wiles

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

The three-inning exhibition between the Chicago Colleens and Springfield Sallies on August 11, 1950, marked the only time the AAGPBL played at Yankee Stadium. (New York Daily News)

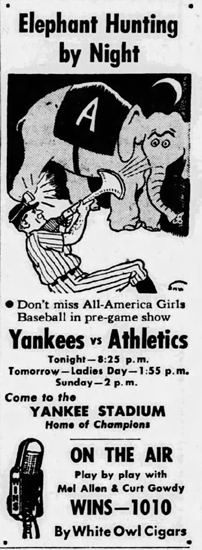

Between 1923 and 2008, Yankee Stadium hosted 6,746 American League and related professional baseball games, including 161 postseason games and four All-Star Games. More than 200 Negro League games have also taken place there. On August 11, 1950, the ballpark hosted its first and only game between two teams of female professional baseball players, when the Chicago Colleens and the Springfield Sallies of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL) played a three-inning exhibition before that day’s contest between the Yankees and the Philadelphia Athletics.1

The New York Times called the game “a spirited exhibition,” noting that the “Colleens, managed by Dave Bancroft, famed Giant shortstop of thirty years ago, won by a score of 1-0.”2 The New York Herald Tribune saw the game differently, noting that the Colleens won, 3-0. “Umpires were provided by the Yankees: Ralph Houk at home plate. Gene Woodling at first, Ed Lopat at second and Allie Reynolds at third.”3

At present, we do not know who got on base, scored, or drove in runs in this historic game, as no box score, scorecard, or narrative game account has yet been found. We do know the name of the first woman to throw a pitch at Yankee Stadium, though: “No other woman had ever pitched off that mound before me,” said Gloria ‘Tippy’ Schweigert, the 16-year-old who started that day for the Colleens.4 This source credits her with throwing a no-hitter in the start, though no game account confirms that.5

In November 2022, this author spoke to all three of the surviving players who took the field that day: Joanne McComb, Mary Moore, and Toni Palermo. All expressed difficulty recalling much beyond the honor of playing in the House That Ruth Built.

“I played first base, I know that,” recalled McComb. “I was more impressed with the surroundings. The game itself, to me, was just another game.”6

Mary Moore played second base and recalled hitting a ball into the infield and running toward first base, where she took a spill on wet grounds after veering off to the right, muddying her bright white uniform. She can’t recall if she was safe or out, but “I would think that I would remember if I was safe.”7

Toni Palermo played shortstop, recalling that Phil Rizzuto loaned her his glove – and she used it in the game. She also could not recall game details, but noted, “I just know that I really enjoyed it, that I had his glove and I felt like a star out there. I was a confident player. I wanted every ball hit to me, no matter what the situation, and with his glove, I felt even more powerful.”8 Palermo also recalled Casey Stengel working with her on double plays before the game, teaching her to time the approaching ball, get it on the hop she wanted, and to just kick the corner of the bag. “And it made a difference,” she recalled.9 None of the three could confirm the game score.

Beyond the lack of a box score, another intriguing loss for history is the fact that, according to Merrie Fidler, the Yankees organization wrote an enthusiastic letter to the AAGPBL after the game, which included the sentence “The game was carried in its entirety on television and there has been a great deal of interesting comment around the city since.”10 This footage has not survived.

Playing in Yankee Stadium was a source of pride for many of the players that day, as they often gave that as their favorite memory when asked on questionnaires, by reporters, and at panel discussions.

“Imagine, if you will, back then, being a girl and playing professional baseball on the field at Yankee Stadium. Think what it must feel like to us, walking and running around the outfield, standing in the same batter’s box where the likes of Babe Ruth, Phil Rizzuto, and Joe DiMaggio had stood. It was truly amazing and exciting for us,” recalled pitcher Pat Brown in her autobiography A League of My Own.11

The Yankees and A’s players were friendly with the female players, and there was much interaction on the field and in the dugouts. Said Jane Moffet, “I … found myself in the dugout with several of the Yankees ball players, I was with Yogi, Whitey Ford, Casey Stengel, and others. Casey and Yogi were very friendly and stayed with us in the dugout talking baseball. I went out and warmed up the pitcher, and we played our three-inning game. Then we stayed for the game. I have been a devoted Yankee fan ever since. All in the life of a rookie.”12

Joanne McComb recalled Johnny Mize: “He was a character. He sat on the bench with us during the game, and offered to trade us chewing tobacco for bubble gum.”13

McComb listed the game as her favorite baseball memory and recalled, “The Yankee players acted as our bat boys in the dugout with us.”14 Mary Lou Kolanko mentioned that “I warmed up playing catch with Phil Rizzuto.”15

Barbara “Bobbie” Liebrich, who along with Pat Barringer was one of the two player-manager-chaperones on the touring teams, remembered that “[a]fter the game I and the other manager (Barringer) were on Paul and Dizzy Dean’s TV show.”16 Liebrich and Barringer were also the keepers of the excellent set of three tour scrapbooks and a photo album documenting the annual tours, which is housed at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown.

“I’m just sorry I broke my ankle, because after that, the teams went up and played at Yankee Stadium, and I missed that game,” lamented Shirley Burkovich.17

“I remember the game at Yankee Stadium,” said Jacqueline “Jackie” Mattson. “What a thrilling experience it was to meet Yogi Berra. His offer to let me use his bat was hilarious. What a club it was! It had a thick handle and was very heavy at the end. I was 5’5” tall and weighed one hundred pounds. If I had swung Yogi’s bat, it would have spun me in a circle, once or twice around. Needless to say, I used my own evenly balanced bat with its nice thin handle.”18

“We were the only girls to play at Yankee Stadium,” Mattson said. “That was an experience in itself. The stadium was the hugest thing that you’d ever seen.”19

Pat Brown, who was in the A’s dugout, said: “We were all talking to the (A’s) players who had come into our dugout, and, at the same time, were cheering for our team playing out on the field. Suddenly everyone became very, very quiet, and we all looked toward the entry to the dugout. A tall thin man with white hair and a nice smile had just entered the dugout. We all knew who he was, and we respectfully waited for him to speak. It was Connie Mack, the manager of the Athletics, a man who was indeed a legend in baseball.”20

“Everybody was in awe,” she said.21 “It turned out that this was to be his last year managing. In 1956, when I read in the paper that he had died, I remembered him as that very special person who took the time to come into the dugout and say hello to some women professional players. Some things you can never forget.”22

“What a thrill! We even met Mr. Connie Mack, wearing his customary vested suit and his straw hat,” recalled Pat Courtney.23 “I was so impressed with Connie Mack – his demeanor, and always so well dressed,” remembered Joanne McComb.24

“We did play in Yankee Stadium which was a great thrill,” recalled player Mary Moore in a 2004 interview with AAGPBL historian Merrie Fidler. “Walking onto that field was like in a movie. It just was so beautiful – manicured. It was – I mean words just can’t describe it, actually. We played very good ball at the time and you could just hear the crowd ‘oooh’ and ‘aaah’ and it was just awesome. It’s really – you can’t even describe it. You know, when we were touring around the country, we played at some nice places and then some of them they were almost like cow pastures.”25

The game in Yankee Stadium came roughly midway during the 1950 traveling exhibition schedule conducted by the two teams. From 1948 to 1950, the Colleens and Sallies toured through much of North America in order to promote the league, generate revenue, and recruit new players.26 The Colleens and Sallies were also considered farm teams, not just scouting the available talent at their many stops, but also refining the skills of those players already on their rosters, in preparation for call-ups to the established, fixed location teams in Midwestern cities like Rockford, South Bend, Peoria, and Kalamazoo.

“We had good, good crowds because half the proceeds would go to some local charity,” noted Mary Moore. “Murray Howe, our public relations guy, he was always ahead of us and he had press coverage and we had to take turns giving interviews on radio in each town that we went into. So we did have good advance publicity.”27

The Liebrich-Barringer scrapbook collection reveals fundraisers to raise money for swimming pool construction; the Fresh Air Fund; a high-school band that needed funds to pay expenses to Chicago to play at the Lions International convention; a scholarship fund for a young pianist to the New England Conservatory; polio benefits; police and fire departments; Boys Club Building Fund; Optimist Club’s Boys Work program; funds for needy families; Community Chest funds; and a city playground fund.28 Admission was usually $1 for adults and 50 cents for children. A few locations had discounted bleacher seats, and at least one Southern venue, Duncan Park in Spartanburg, South Carolina, offered “Colored Bleachers” for 50 cents.29

Between June 3 and September 4, the players traveled by bus through Illinois, Ohio, West Virginia, and points southward, including Roanoke, Asheville, Macon, Knoxville, and Hazard, Kentucky. Then it was over to Hagerstown, Maryland, and then up through New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, then back south for games in Washington (where they played two games at Griffith Stadium), Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware. Then it was New York again, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and games in Sherbrooke and Montreal, Quebec. They finished up by working their way west across New York and Ohio.30 The teams scheduled 95 games in that stretch, playing 83, with 12 rainouts.31

The players were mostly in their late teens or early 20s, and only one, Canadian center fielder Joan Schatz, was married at the time.32 The bus rides were long, often conducted overnight, with players assembling on the bus after their postgame showers. “The bus driver, Walt, loved to sing along with those songs, he had a beautiful voice, we traveled at night, and Wimp (Baumgartner) would stand up in front of the bus with him, and we’d sing songs all night. We had good singers on those teams!” recounted Isabel Maria Lucila Alvarez de Leon y Cerdan, also known as Lefty Alvarez. “The days were ours to do with whatever we wanted. We had to do laundry, and catch up on our sleep, and do letter-writing. But in a couple of places, like New York, we went to Radio City Music Hall and Coney Island. It was a beautiful experience to get to do that and travel all over. We played through all the South, the East, the New England states and Canada, so there are places I would have never gotten to see, to do all this and get paid for it was really nice.”33

Speaking of the 1949 tour, Jane Moffett reminisced: “We traveled 26,000 miles that first summer in a bus. We played every day and prayed for rain because that was the only way we got time off. We could play a game and the next stop could be 200 miles away. A lot of police departments, fire departments and organizations would sponsor us as a fundraiser and we got called frequently to be on radio shows.”34 Anna Mae O’Dowd added, “There was a lot of singing and a lot of jokes on the bus. It was fun. Of course, you got very tired too. I remember that well.”35

Mary Moore, who led the Sallies in games played (77), hits (75), total bases (96), home runs (3), runs scored (65), and RBIs (48) in 1950, recalled, “We toured 21 states and Canada that first year. On the farm team level, we got $25 a week and $21 for meals that wasn’t taxable, plus all of our travel and housing expenses taken care of.”36

Many of these young women had never been away from home, and the opportunity to see the country, and Canada, was educational. Massachusetts native Pat Brown was surely not the only player whose eyes were opened to segregation: “I learned a lot that summer of 1950 while traveling through the segregated South. I had never seen such signs before as ‘Colored Only,’ or ‘White Only.’ Even some of the posters announcing our games advertised separate seating for ‘Colored.’ I was only a teenager, but after what I had seen, nobody had to tell me that segregation was wrong; I just knew it. Those images and other situations stayed with me, and I became a firm believer in civil rights and equality. Even today, I cannot erase those images from my mind.”37

A week before the Yankee Stadium game, the AAGPBL made national news when former Yankee star Wally Pipp called 26-year-old Rockford Peaches first baseman Dottie Kamenshek, a perennial all-star who was hitting .343 at the time, the “fanciest-fielding first baseman I’ve ever seen, man or woman.”38 Shortly thereafter, Kamenshek and AAGPBL President Fred Leo were contacted by officials with the Fort Lauderdale team and the Florida International League, offering to buy her out. Both Kamenshek and Leo turned down the offers. Kamenshek thought the offer was not sincere, and Leo said, “Rockford couldn’t afford to lose her. I also told them we felt that women should play baseball among themselves and that they could not help but appear inferior in athletic competition with men.”39

When asked about Pipp’s comments, Bancroft replied that “Kamenshek was ‘an extraordinary player,’ but that he leaned against any woman being able to play in the major leagues. But he also added, ‘Remember, it was only a short time ago that most major league players, managers, and sportswriters rejected the idea of Negroes ever playing the big top. Time marches on.’”40

Of managing the women’s teams, Bancroft told writer Will Wedge, “It’s fun here, mixed with the usual headaches of a skipper, and it pays better than the minors. And it sure comes under the head of new experiences, and even at 57, and as gray-haired as I am, I can be attracted by novelty.

“But don’t get me wrong. This girls baseball is more than a novelty, because it is good brisk baseball, and we give the customers a fast show, the games running only about an hour and a half. And I’m telling you that the adeptness of 99% of these dolls simply amazes me and their sport has caught on well in the Midwest. … These girls just can’t get enough baseball. They want to bat for an hour before the game, but after twenty minutes on the mound, I’ve had more than enough exercise.”41

Historian Merrie Fidler has also discovered that the AAGPBL planned, but apparently never held, another game in Yankee Stadium in the 1950 season. According to an article she found in a Scranton newspaper, “The (Kenosha) Comets and (Racine) Belles are scheduled in a nine-inning exhibition as a preliminary to the regular American League scheduled contest between Chicago and the Yankees. … Considerable interest has been evidenced throughout the East in the game played by the AAGPBL after barnstorming tours by farm clubs last year. The two teams will fly by a chartered airliner to New York, and will return by air in time to resume their scheduled games at Fort Wayne and South Bend.”42

In myriad interviews conducted over the last 30 years, since the film A League of Their Own was released, a trope emerges that these young women used their high salaries and newfound freedom to blaze new trails for their gender, which often involved higher education – at that time not at all common for young women. Pat Brown’s autobiography repeats that pattern.

In a related article, Brown sums up, as no other player has done, the value of playing in the AAGPBL. This is the list of “Lessons from Pat Brown’s Baseball Life” that she wrote about: “Toughness, assertiveness, teamwork, belief in self, independence, broader perspective, acting under pressure, and courage.”43 One quality she did not list was confidence. But she addressed it elsewhere: “I myself was only 17, 18 when I went out there to play. I was very shy, quiet through high school. The league changed me. It gave me confidence, it built me up. I finally realized that I wasn’t a freak because I was athletic. Before I started playing, people said to me, ‘It’s wrong that you want to play baseball. It’s okay when you’re a little kid, when you’re a tomboy.’ Once I became a professional baseball player, I felt vindicated.”44

Pat Brown went on to earn not just her master’s in library science, but also her law degree and a master’s in divinity.45

The entire tour was a rare opportunity for young women to expand their horizons through travel, athletic achievement, and making good money while enlightening crowds and opening eyes all across North America. We’ll give the last word to Mary Moore: “Playing and getting to see the country like that and getting paid for it was more than you could ever dream of – I mean it was a dream come true – what else? You loved to play ball and you’re seeing the country and you’re traveling and everything and you couldn’t ask for anything more.”46

Women did have one more chance to play at Yankee Stadium, in a Negro American League doubleheader on July 11, 1954, between the Kansas City Monarchs and the Indianapolis Clowns. A newspaper article in advance of the game said, “The girls take a back seat to no one on the field either. They both really play baseball and Miss Toni Stone of the Monarchs, and Miss Connie Morgan of the Clowns have displayed plenty of ability.”47 While advance publicity had both women slated to play second base, the lack of a box score makes it currently impossible to know if either actually played.

TIM WILES is the library director at the Guilderland (New York) Public Library. He was the director of research at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library from 1995 to 2014. He co-authored Baseball’s Greatest Hit: The Story of Take Me Out to the Ball Game in 2008. He co-edited Line Drives: 100 Contemporary Baseball Poems in 2002. His blog on women and girls in baseball can be read at grassrootsbaseball.org.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The author is grateful for research help from Merrie Fidler, official historian of the AAGPBL Players Association; Brian Richards, senior museum curator of the New York Yankees; Cassidy Lent and Rachel Wells of the National Baseball Hall of Fame library; former players Joanne McComb, Mary Moore, and Toni Palermo; Adam Berenbak of the National Archives; and historians Carol Sheldon and Ryan Woodward.

NOTES

1 John Drebinger, “Yanks Bench DiMaggio, Stagger to 7-6 Victory Over Athletics,” New York Times, August 12, 1950.

2 Drebinger.

3 Untitled New York Herald Tribune article dated August 12, 1950, retrieved from Liebrich-Barringer AAGPBL Tour Scrapbooks (MSS 10, 1-D-2), National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York, September 30, 2022.

4 W.C. Madden, The Women of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League: A Biographical Dictionary (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1997), 220.

5 Madden, 220.

6 Joanne McComb, telephone interview, November 22, 2022.

7 Mary Moore, telephone interview, November 6, 2022.

8 Toni Palermo, telephone interview, November 6, 2022.

9 Palermo interview.

10 Merrie A. Fidler. The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2006), 110.

11 Patricia I. Brown, A League of My Own: Memoir of a Pitcher for the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003), 66.

12 Kat D. Williams, Isabel “Lefty” Alvarez: The Improbable Life of a Cuban American Baseball Star (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 59.

13 McComb interview.

14 Joanne McComb. Player questionnaire in the research files of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, 1997.

15 Joanne McComb, Touching Bases, the newsletter of the AAGPBL Players Association, January 2005.

16 Mary Lou Kolanko, Touching Bases.

17 Madden, 148.

18 Brown, 173.

19 Andy Horschak, “Brewers, ex-Comet Preserve the Legacy of the AAGPBL,” undated clipping, likely from the Kenosha News, retrieved from Liebrich-Barringer AAGPBL Tour Scrapbooks.

20 Brown, 67.

21 Dennis Daniels, “Move over Cobb, Ruth & Williams!” Boston Herald, October 12, 1988: 31.

22 Brown, 67.

23 Brown, 162.

24 McComb interview.

25 Mary Moore, interview with AAGPBL historian Merrie Fidler, conducted by phone in March 2004. Interview transcript provided by Merrie Fidler.

26 https://www.aagpbl.org/history/league-history. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

27 Moore interview.

28 Numerous articles from the AAGPBL Tour Scrapbooks.

29 Numerous newspaper game advertisements from the AAGPBL Tour Scrapbooks.

30 Tour schedule and results from the AAGPBL Tour Scrapbooks.

31 Typescript of schedule and results, AAGPBL Tour Scrapbooks.

32 Mary Hayes, “Yank Stadium to Queen City: Diamond Damsels Hit With Patrons,” News (city unidentified) from AAGPBL Tour Scrapbooks.

33 Jim Sargent, We Were the All-American Girls (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013), 281.

34 Jessica Driscoll. “Former Pitman Resident Honored as Baseball First,” Gloucester County Times (Woodbury, New Jersey), July 5, 2010.

35 Katie Sartoris. “Annie O’Dowd Recalls Time Spent in All-American Girls Professional Baseball League,” Villages Daily Sun (The Villages, Florida), May 31, 2013.

36 Pat Andrews. “Female Star Returns Downriver: LP Grad Depicted in ‘A League of Their Own,’” Heritage Newspapers/News-Herald (Taylor, Michigan), October 25, 1995: 4-C.

37 Brown, 70-72.

38 Fidler, 223.

39 Ed Sainsbury (United Press), “Florida Nine Tries to Sign Woman Player,” unknown newspaper, August 3, 1950, AAGPBL Tour Scrapbooks.

40 Will Wedge, “Setting the Pace,” New York Sun, August 5, 1948, AAGPBL Tour Scrapbooks.

41 Wedge.

42 “Girl Ball Teams in Stadium Game: Jean Marlowe to Play in New York July 17,” Scranton (Pennsylvania) Times Tribune, May 31, 1950: 41.

43 Patricia I. Brown and Elizabeth M. McKenzie, “First Person … A Law Librarian at Cooperstown,” Law Library Journal, Volume 93:1. Winter, 2001.

44 Liz Galst, “The Way It Was: A Real Professional Ballplayer Looks at League,” Boston Phoenix, July 3, 1992: Arts Section 7.

45 Carol Sheldon, “Patricia Brown,” Boston Herald. Player profile provided at AAGPBL website. https://www.aagpbl.org/profiles/patricia-brown-pat/219. Retrieved November 22, 2022.

46 Mary Moore interview.

47 “Clowns-KC Monarchs at Stadium Sunday: Bitter Rivalry for NAL Girl Players in Focus,” New York Amsterdam News, July 10, 1954: 23.