Live From Yankee Stadium: A Brief History of the Yankees on Radio

This article was written by Donna L. Halper

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

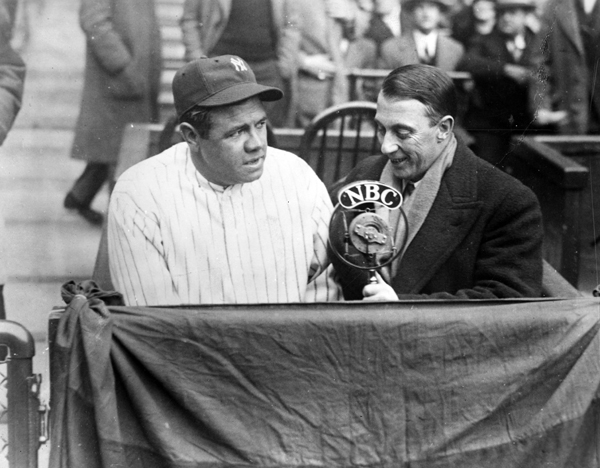

Radio broadcasts of Yankees games in the 1920s were sparse, but Graham McNamee (shown here with Babe Ruth) often called the few that did make the air. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

For New York Yankees fans, Wednesday, April 18, 1923, was a momentous occasion: That was the day the brand-new Yankee Stadium made its debut. More than 74,000 fans were in attendance, and thousands more tried (and failed) to get in.1 There was national interest in the game, thanks in large part to the popularity of Babe Ruth; as a result, the press box was crowded with reporters from a wide range of publications. But one group was absent from the day’s events: radio broadcasters.

That really wasn’t surprising. Commercial radio was not even two years old, and remote broadcasts were still in their infancy. But in addition to technological challenges, one other factor kept the home opener off the air – opposition from the Yankees management, the baseball writers, and the Western Union Telegraph Company. Yankees management believed that allowing the games to be broadcast would cut into attendance. The writers worried that broadcasting the game, or even giving the scores, would cut into sales of newspapers.2 And Western Union had established strong business ties with the newspapers, offering exclusive access to scores and summaries of games from all over the country. If radio stations could broadcast the games, the telegraph company’s importance would be diminished.3

While it might have been courteous for the Yankees to broadcast the sold-out 1923 home opener, the fans probably weren’t expecting it, given how new radio broadcasting was. Meanwhile, a few radio stations were beginning to broadcast scores and brief summaries, and these reports were welcomed by the listeners, especially fans eager to know how Babe Ruth had done that day.4 There was also a new sports commentary program, one of the first of its kind. It was hosted by William J. “Bill” Slocum, then of the New York Tribune; he had covered the Yankees for nearly a decade. Even Slocum’s fellow beat reporters enjoyed listening to his radio show, with his anecdotes about games he had seen, and players he knew – including Babe Ruth.5 (Slocum was also Babe Ruth’s ghostwriter, something most fans probably did not realize.6)

During the regular season in 1923, there were no broadcasts of Yankees games, but arrangements were made to put the World Series between the Yankees and the Giants on the air, on stations WJZ and WEAF, live from Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds. It wasn’t the first time World Series baseball was broadcast live, nor the first time that a Yankees game was broadcast. A year earlier, anyone with a radio had heard the Yankees play the Giants in the 1922 World Series, but since Yankee Stadium had not yet been completed, the games originated from the Polo Grounds, with sportswriting legend Grantland Rice doing the play-by-play.

The announcers for the 1923 World Series were Major J. Andrew White, editor of a radio magazine, The Wireless Age, on WJZ, and Graham McNamee, a former vocalist and now an up-and-coming announcer, on WEAF. The broadcasts almost didn’t happen; the owners did not want to grant their permission, but Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis stepped in and overruled them.7 Interestingly, some of the same baseball writers who had expressed opposition to broadcasting any games, including the president of the Baseball Writers Association, Fred Lieb, and fellow baseball writers Bozeman Bulger and Hugh Fullerton, went on the air to offer commentary during the Series.8

But if the fans expected more Yankees baseball on the air in 1924, they were disappointed. All that was available were nightly scores provided by some local stations. The World Series was broadcast again, but the Yankees were not part of it, since they didn’t win the pennant. The next time a Yankees game was broadcast was Opening Day 1925, when the World Series champion Washington Senators came to Yankee Stadium. Unfortunately for Yankees fans, the game was only broadcast by a Washington station, WRC, and it was not broadcast live. It was a re-creation, originating from the broadcasting studio of the Washington Times newspaper. Charles Matson was the announcer, and he narrated the story of the game “just as it [was] telegraphed from Yankee Stadium by R.D. Thomas of the Times sports staff.”9

It wasn’t until 1926 that another Yankees game was broadcast live. On April 13, 1926, Boston Red Sox owner Bob Quinn, who had also kept the games off the radio, relented and permitted the home opener against the Yankees to be broadcast live from Fenway Park,10 with Boston Traveler baseball writer Gus Rooney doing the play-by-play on station WNAC.11 Then, on April 21, the Yankees also broadcast their home opener, against the Red Sox, with Graham McNamee at the microphone, over WEAF.12 There is no available evidence that suggests this was coordinated by the Red Sox and Yankees; rather, it appeared to be a coincidence. Quinn made his decision so suddenly that even the Boston sportswriters were surprised – when they received the press release, they didn’t even know who would be doing the play-by-play.13 As for the Yankees, team management was convinced there was no need to broadcast more than one game, and the home opener seemed a good choice. At that time, teams received no revenue from putting a game on the air, and ballclubs like the Yankees that already had good attendance saw little incentive to allow any broadcasts.14 Thus, while the 1926 home opener got on the air, no other Yankees games were broadcast until the team reached the World Series.

Throughout 1926, a growing number of radio stations were linking up to broadcast certain important current events, like political conventions, presidential speeches, or the World Series. There was no national network yet (though the National Broadcasting Company would soon make its debut), but by October 1926, the World Series games were scheduled to air on stations in 22 cities; announcers Graham McNamee and Phillips Carlin opened the Series live from Yankee Stadium as the Yankees played the St. Louis Cardinals.15 (Carlin and McNamee were becoming a popular sportscasting duo. Since Carlin joined WEAF in November 1923, they had collaborated on coverage of numerous sporting events, including college football and major-league baseball.)

By 1928, it was finally possible to hear the World Series from coast to coast, thanks to NBC, and a second network, CBS (then known as Columbia). Both networks had announcers at Yankee Stadium on October 4: McNamee and Carlin handled the games for NBC, and at Columbia, it was the team of Edward “Ted” Husing and J. Andrew White. White, a veteran sportscaster, was now the president of Columbia; Husing had worked for WJZ as a staff announcer for musical programs but had transitioned to covering sports, including World Series broadcasts. In 1929 both networks also broadcast the home opener between the Yankees and Red Sox, on April 18, live from Yankee Stadium. McNamee did the play-by-play for NBC affiliates, and Ted Husing was behind the microphone for Columbia stations.16

Many Yankees fans undoubtedly enjoyed listening to the network announcers; although there were no ratings services yet, there was growing evidence that listeners approved of baseball play-by-play, and radio stations were receiving fan mail and phone calls saying so. For example, Harry Hartman, sports commentator at WFBE in Cincinnati, noted that the broadcasts were turning more people into baseball fans. He said that “women and children have become more acquainted with [baseball], and are eager to accept when invited to attend a game.”17 The belief that the radio broadcasts were helping to create new fans was echoed by Bob Quinn of the Red Sox, Sam Breadon of the Cardinals, and several other owners and executives who had previously objected to putting the games on the air.18

But Yankees management did not agree. Other than Opening Day, no other Yankees games were available in 1929. And there was little indication that that policy would change. Ed Barrow, secretary of the Yankees, said in early 1930 that no games would be broadcast except for Opening Day because he continued to believe more broadcasts would have a negative impact on attendance.19 Meanwhile, the Yankees were increasingly becoming outliers: By 1930, a growing number of major-league teams were relaxing their “no radio” policy and allowing more broadcasts during the season. As further proof that the owners were no longer unified on the subject, when major-league owners gathered in early December 1931 for their winter meetings, an attempt by some owners to ban all broadcasts in 1932 was quickly blocked; Chicago Cubs President William L. “Bill” Veeck (the elder) was among the faction that strongly supported broadcasting the games.20

But the Yankees ownership held firm.21 In 1931 and 1932, just the home opener got on the air. The Yankees won the pennant in 1932, and in late September, the networks began broadcasting the World Series, with the Yankees playing the Chicago Cubs. And the night before Game One, New York listeners heard “The Old Maestro,” bandleader Ben Bernie, offering something for baseball fans during his popular WEAF and NBC program. He was joined by Yankees manager Joe McCarthy and Cubs manager Charlie Grimm, each telling listeners why their team was going to win.22 (It was McCarthy whose prediction was right – the Yankees swept the Cubs in four games.)

However, to the dismay of Yankees fans, even the Opening Day games ceased to be broadcast during the mid-1930s. The only option was network coverage if the Yankees made it back to the World Series (which they did again in 1936). By now, baseball was on the air in an ever-increasing number of cities, and it was even sponsored – stations were making money from airing the games. And rather than depressing attendance, it was keeping fan interest high – something Bill Veeck had been saying since 1927.23

In April 1938 things finally changed, thanks in part to Bill Slocum. He had retired from sportswriting and was hired by General Mills as a “contact man”: a liaison between the company, which sponsored numerous baseball games, the radio stations that broadcast them, and the various team owners. Slocum’s duties also included improving relationships with the announcers who called the games, and even providing some training (as well as letting them know what the sponsor expected – which seemed to be a balancing act between being objective and factual about the play-by-play, but being enthusiastic about the sponsor’s products).24

Slocum approached the Yankees management about getting on the air; surprisingly, he got a “yes.” We may never know why: Perhaps it was because of his credibility as a longtime baseball writer, or his powers of persuasion. (The sponsors credited him with negotiating the deal, which put the games on WABC in New York.25) Then again, perhaps it was due to Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert having to miss attending the 1938 World Series due to a lingering illness, and relying on the radio networks to listen to the games.26 But whatever the reason, by year’s end, Ruppert announced that in 1939, Yankees games would be on the radio; he said this was his gift to people who were hospitalized, or who couldn’t attend the games due to health problems. (However, the reporter covering the story noted that Ruppert wasn’t being totally altruistic: The sponsors would be paying about $100,000 for the rights to broadcast the games.27) And the decision may also have been influenced by the early December 1938 announcement by Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Larry MacPhail that the Dodgers had agreed to broadcast their games in 1939.28 MacPhail received about $75,000 from sponsors for the rights.29

WABC’s lead announcer for the 1939 season was veteran broadcaster Arch McDonald, previously the voice of the Washington Senators. McDonald’s duties included hosting daily sports reports, as well as play-by-play of both the Yankees and the Giants home games; his assistants on those broadcasts were a former newscaster named Garnett Marks, and an up-and-coming sportscaster named Mel Allen. Although some listeners found McDonald’s style too “folksy,” most fans seem to like him;30 they especially liked his clever nicknames for some of the players – he called Joe DiMaggio the Yankee Clipper, and it stuck.31 But at season’s end, McDonald returned to the Washington Senators. His replacement was his former assistant, Mel Allen. A graduate of the University of Alabama, with a law degree, Allen fell in love with sportscasting; hired by CBS in 1937, he was trained by Ted Husing.32 Allen was just 27 years old in 1940, making him one of the youngest major-league radio announcers.33 His sidekick was Jay C. Flippen, a former comedian turned sportscaster, and his statistician was Jack Slocum (one of Bill Slocum’s sons).

But in 1941 no agreement was reached, and while the Brooklyn Dodgers were on the radio (on WOR, with Red Barber doing the play-by-play, assisted by Al Helfer), the Yankees were not. Fortunately for their fans, the Yankees reached the World Series, which was broadcast via the Mutual Broadcasting System, on WOR. By April 1942, the Yankees games were back on the air, also on WOR; General Mills was the main sponsor again, with R.H. Macy as the cosponsor. Mel Allen returned to do the play-by-play, assisted by Cornelius “Connie” Desmond. Then, in 1943, the Yankees announced that no broadcasts of their games would be permitted, and the Giants did the same. This time, it was a dispute over fees: In 1942, sponsors had reportedly paid $75,000 to each team for the broadcasting rights.34 In 1943, according to Yankees management, no sponsors came forward who were willing to pay that amount. Ed Barrow, president of the Yankees, and Giants executive Leo Bondy, were unwilling to broadcast anything for which there was no sponsorship, and for which their clubs were not paid. As a result, the games remained off the air for the season.

Fortunately for the listeners, both the Yankees and the Giants obtained sponsors for the 1944 season for all home games; the broadcasts moved to station WINS, where Don Dunphy, best known for covering boxing, and Bill Slater, a former WOR staff announcer, did the play-by-play. Both got good reviews, but the next year, Dunphy was replaced by Al Helfer. Bill Slater stayed on, and the games remained on WINS. (If you are wondering about Mel Allen, he was serving in the Army for three years.)

When Allen returned from the service in 1946, he also returned to the broadcast booth, where he remained for the next 18 years – on WINS, then WMGM, and finally WCBS. During those years, he had numerous partners, including Russ Hodges, Curt Gowdy, Joe E. Brown, Red Barber, and former Yankees shortstop Phil “Scooter” Rizzuto, who became a broadcaster in 1957. (Almost immediately, he was identified with his catchphrase, “Holy Cow.”)35 Allen, too, had catchphrases – especially one that he popularized circa 1949, “How about that!” Like other broadcasters of the late ’40s, Allen was not only asked to do radio play-by-play; he had to adapt to a new mass medium – television. During the 1947 World Series, when the games were televised for the first time, Allen teamed up with Red Barber, who was still announcing Dodgers baseball, to do the play-by-play on both radio and TV. Barber joined the Yankees broadcast team in 1954,36 and the two veterans worked together for the next decade.

Allen was unexpectedly fired at the end of the 1964 season.37 At first there was no official announcement, but when Phil Rizzuto suddenly took Allen’s place on the TV-radio broadcasts of the 1964 World Series, reporters began asking questions. Red Barber was concerned too: he knew that if Allen was no longer the Voice of the Yankees, it would break his heart.38 As it turned out, in late November, the Yankees finally announced that Allen’s contract would not be renewed.39 Several weeks later, Rizzuto was named the lead announcer for Yankee baseball; he was joined by a new member of the broadcast team, former St. Louis Cardinals catcher Joe Garagiola.40 In addition, former Yankees second baseman Jerry Coleman, who had been added to the broadcast team in February 1963, remained in the booth, and so did Red Barber. But then, in September 1966, the popular Barber was suddenly fired, much to the consternation of many fans and baseball writers, who thought the Yankees management had made a terrible decision.41 As for Garagiola, he stayed a Yankees broadcaster for only three seasons, before going on to a long career with NBC; Coleman, who spent a total of seven years calling Yankees games, left at the end of the 1969 season to join the California Angels broadcast team.

Rizzuto remained in the Yankees broadcast booth for four decades; he was heard on various New York radio stations (WHN, WMCA, WINS, and WABC), and seen on WPIX-TV (Channel 11). Two of his best-known broadcasting partners were Frank Messer (a former play-by-play announcer for the Baltimore Orioles)42 and Bill White (a former major-league first baseman for the Giants, Cardinals, and Phillies; when he joined the Yankees broadcast team in early 1971, he was the only Black play-by-play announcer in the majors).43 Not only did Rizzuto have a long broadcasting career, during which he called many key moments in Yankees history; he also became part of pop culture when his voice was heard on a classic 1977 album rock song by Meatloaf, “Paradise by the Dashboard Light.”

In 1987 the Yankees finally brought in a new radio team: Hank Greenwald and Tommy Hutton. Greenwald (whose real name was Howard, but who changed it to Hank in honor of Hank Greenberg of the Detroit Tigers, a player he idolized while growing up in Detroit)44 had previously been a play-by-play announcer with the San Francisco Giants, and Hutton, a former journeyman player who spent time with the Dodgers, Phillies, Blue Jays, and Expos, had worked for ESPN before doing play-by-play for the Expos. The two men were hired so that Rizzuto and White could focus exclusively on their work for WPIX-TV.

That paved the way for John Sterling, who previously did play-by-play basketball for the Atlanta Hawks and baseball for the Atlanta Braves. Another broadcaster who had a long career on Yankees broadcasts, he was hired for the 1989 season, after WABC – which had been broadcasting the games on radio since 1981 – did not renew the contracts of Greenwald and Hutton.45 Sterling was born and raised in New York and was glad to be back home. He was expected to bring “an irreverent and colorful tone” to the broadcasts, as well as more enthusiasm (and by some accounts, more willingness to be friendly with the sponsors).46 Over a career of more than three decades, Sterling became known for his remarkable work ethic: He broadcast 5,059 consecutive games, including the postseason, from September 1989 to July 2019.47 And as of the 2022 season, Sterling was still on the air, now in his 80s, with no known plans to retire. Among Sterling’s memorable quirks was his call whenever the Yankees were victorious: an elongated “Theeeeeeeee Yankees win!!!”

Among Sterling’s most popular sidekicks was Michael Kay. A former sportswriter who covered the Yankees for the New York Post and then the New York Daily News,48 he teamed up with Sterling on WABC in 1992. After a decade on radio, Kay made the move to the television side in 2002, broadcasting the games for the Yankees Entertainment & Sports Network (YES). But he maintained ties with radio too, hosting a sports-talk program on 1050 ESPN; his radio show (and ESPN’s entire programming lineup) later moved to FM, in April 2012.

And in a field dominated by men, the Yankees were among the first to hire a female sportscaster. Suzyn Waldman, who was with New York sports-talk radio station WFAN from its debut in 1987, distinguished herself as one of New York’s most knowledgeable broadcasters, male or female. In 2005, she joined the Yankees broadcast team on WCBS Radio, which had been carrying the games since 2002. Waldman’s hiring made her the major leagues’ first full-time female color commentator.49

Today, the entire schedule of Yankees baseball is available – online, on TV, and on radio, a far cry from the days when fans were fortunate if they heard one game a year. The team has had a succession of well-respected radio announcers; many Yankee fans regard them as part of the family. As Bill Veeck pointed out more than 90 years ago, broadcasting the games hasn’t hurt attendance: then, as now, fans appreciate being part of the action, whether in person or on their various devices.

DONNA L. HALPER is an associate professor of communication and media studies at Lesley University in Massachusetts. She joined SABR in 2011, and her research focuses on women and minorities in baseball, the Negro Leagues, and “firsts” in baseball history. A former radio deejay, credited with having discovered the rock band Rush, Dr. Halper reinvented herself and got her PhD at age 64. In addition to her research into baseball, she is also a media historian with expertise in the history of broadcasting. She has contributed to SABR’s Games Project and BioProject, as well as writing several articles for the Baseball Research Journal.

NOTES

1 “74,200 See Yankees Open New Stadium; Ruth Hits Home Run,” New York Times, April 19, 1923: 1.

2 “Baseball Writers Oppose Radio Use,” New York Times, May 26, 1923: 11.

3 C.W. Horn, “Broadcasting the World Series,” Radio Age, December 1922: 12.

4 Billy Kelly, “Before and After,” Buffalo Courier, April 19, 1923: 11.

5 Zipp Newman, “Dusting ’Em Off,” Birmingham (Alabama) News, May 14, 1943: 29.

6 Dave Anderson, “The End of the Latest Literary Lion,” Raleigh (North Carolina) News and Observer, October 9, 1988: 20B.

7 James R. Walker, Crack of the Bat: A History of Baseball on the Radio (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 29.

8 Raymond Francis Yates, “Reporting Baseball to Millions,” Wireless Age, November 1923: 25, 27-28.

9 “WRC and the Times to Broadcast Game,” Washington Times, April 14, 1925: 2.

10 While it took Bob Quinn until 1926 to permit even one Red Sox broadcast, as I wrote about for SABR, he gradually became a believer in having some of the games on the air; but my research has not found any quotes from 1926-1929 that explain what changed his mind. However, by the early 1930s, he was defending the broadcasts and praising Red Sox play-by-play announcer Fred Hoey. For example, in 1932, he said he believed that “the broadcasting of big league games helps the game and the clubs, and that it even stimulates the sale of the papers carrying the stories of the game.” Burt Whitman, “Hoey’s Baseball Broadcasts Not Definitely Lost to Fans; Up to Leagues, Says Quinn,” Boston Herald, October 20, 1932: 30.

11 “Gus Rooney’s Larynx Gets a Workout.” Boston Traveler, April 14, 1926: 16.

12 “Broadcast Play By Play Yankees-Red Sox Game,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 19, 1926: 4A.

13 “WNAC to Broadcast Red Sox Game Tuesday,” Boston Globe, April 12, 1926: 16.

14 Walker, Crack of the Bat, 52.

15 “Station WJZ Linked with Stations Which Will Radiate Play by Play Description of Today’s Game, Beginning at 1:45 o’Clock,” New York Times, October 3, 1926: XX15.

16 “Radio Program,” New York Daily News, April 16, 1929: 30.

17 “World’s Series Games to be Broadcast,” Montréal Gazette, September 22, 1930: 24.

18 James F. Donahue, “More Ball Games to Go On Air This Year Than Ever Before,” Battle Creek (Michigan) Enquirer and Evening News, March 23, 1930: 12.

19 World’s Series Games to be Broadcast,” Montréal Gazette, September 22, 1930: 24.

20 John B. Foster, “Rumor Formation of Third Major League,” Yonkers (New York) Herald, December 7, 1931: 17.

21 James F. Donahue, “Most Major League Baseball Games Will Be Broadcast but Minor Managers Still Hesitate,” Miami (Oklahoma) News-Record, March 28, 1930: 8.

22 “World Series Talk Fest,” New York Daily News, September 27, 1932: 34.

23 Walker, Crack of the Bat, 86.

24 “Promotion Methods for Baseball Games Outlined at General Mills Gathering,” Broadcasting, May 1, 1939: 36.

25 “Giants and Yanks Complete Arrangements for Broadcasting of Their Home Contests,” New York Times, January 26, 1939: 29.

26 Tommy Holmes, “Cubs Bank on Bryant to Halt Yanks in Third,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 8, 1938: 1, 7.

27 “Ruppert Yields to Bring Cheer to Shut-Ins; Also $100,000,” Akron Beacon Journal, December 23, 1938: 20.

28 “Dodger Baseball to be Broadcast,” New York Times, December 7, 1938: 29.

29 “$75,000 Lures Dodgers to Radio, Giants and Yankees Due to Follow,” Boston Globe, December 7, 1938: 20.

30 J. Anthony Lukas, “How Mel Allen Started a Lifelong Love Affair with Baseball,” New York Times, September 12, 1971: SM 74.

31 Bob Considine, “On the Line,” Scranton Tribune, July 1, 1939: 13.

32 Richard Sandomir, “Mel Allen Is Dead, Golden Voice of Yankees,” New York Times, June 17, 1996: B9.

33 Jack House, “Alabama,” Birmingham News, March 31, 1940: S5.

34 “Yanks, Giants Ban Action Broadcasts,” Broadcasting, May 10, 1943: 45.

35 Harold A. Nichols, “All Star Grid Clash Due on Channel 10,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, August 4, 1957: 5F.

36 Harold C. Burr, “Voice of Brooklyn Headed for Yanks,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 28, 1953: 19.

37 J. Anthony Lukas, “How Mel Allen Started a Lifelong Love Affair with Baseball,” New York Times, September 12, 1971: SM 78.

38 Bob Edwards, Fridays with Red – A Radio Friendship (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), 160-161.

39 Val Adams, “Yankees Schedule Omits Mel Allen,” New York Times, November 25, 1964: L75.

40 “Joe Garagiola Replaces Mel Allen,” Ithaca (New York) Journal, December 18, 1964: 17.

41 Doug Dederer, “Orioles Yes – Yankees No,” Orlando Evening Star, October 6, 1966: 4A.

42 Kay Gardella, “Messer Yankee Voice,” New York Daily News, January 12, 1968: 84.

43 Joe Trimble, “Bill White Joins Yank Telecast Team; First Negro,” New York Daily News, February 10, 1971: C30.

44 Harvey Araton, “New Sounds in the Bronx,” New York Daily News, February 5, 1987: 65.

45 Roger Fischer, “Sierens Won’t Call Any NFL Games for NBC This Season,” Tampa Bay Times, November 11, 1988: 4C.

46 Stan Isaacs, “New Voices in Town Shoot from the Lip,” Newsday (Long Island, New York), April 2, 1989: B23.

47 “Broadcaster’s Long Streak to End,” Tampa Bay Times, July 3, 2019: C5.

48 Andrew Gross, “Two of a Kind: WABC’s Sterling and Kay,” White Plains (New York) Journal News, April 2, 2000: 10K.

49 Steve Zipay, “Listeners Need to Give Waldman Fair Chance,” Newsday, March 1, 2005: A53.