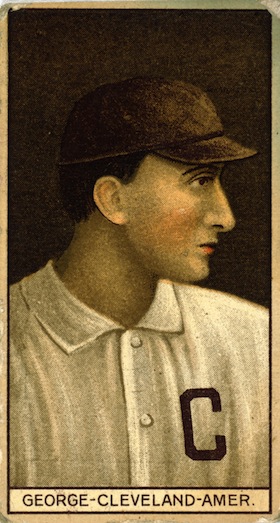

Lefty George

On August 15, 1940, the York Bees defeated the Trenton Senators 3-2 in a Class B Interstate League game. What made this contest noteworthy was that the winning pitcher for York was a 54-year-old former major leaguer by the name of Lefty George. After the game George told the Associated Press, “I’m feeling fine. I’m not the least bit tired and there is no sign of soreness whatsoever in the old arm. I believe I have enough stuff to teach these young men a lot. I propose to play the game just as long as my arm holds out and from present indications that is likely to be a long while.”1

On August 15, 1940, the York Bees defeated the Trenton Senators 3-2 in a Class B Interstate League game. What made this contest noteworthy was that the winning pitcher for York was a 54-year-old former major leaguer by the name of Lefty George. After the game George told the Associated Press, “I’m feeling fine. I’m not the least bit tired and there is no sign of soreness whatsoever in the old arm. I believe I have enough stuff to teach these young men a lot. I propose to play the game just as long as my arm holds out and from present indications that is likely to be a long while.”1

Thomas Edward “Lefty” George was born in the Lawrenceville section of Pittsburgh on August 13, 1886. He was the youngest of six children born to Thomas and Katherine George. The Georges, both of German descent, were married in 1850. Thomas worked as a laborer to support his family.

George, who went by his middle name of Edward, attended O’Hara Parochial School before moving on to Pittsburgh High. As a youngster he took up baseball, pitching for local amateur teams in the Steel City area. Around this time the George family began experiencing financial problems. In order to make ends meet, Edward dropped out of high school, taking a job working for the Ward Baking Company driving a bread wagon. George continued to play ball in his spare time, pitching for the Beltzhoover team in a local semipro league. While playing for Beltzhoover he was discovered by Richard Guy, a sports writer for the Pittsburgh Gazette Times. Guy signed the promising southpaw for his traveling all-star baseball team called the Collegians. Several major leaguers got their start with Guy’s Collegians: Jim Shaw, Gene Steinbrenner, Cy Rheam, Jack McCandless, and Elmer Smith. One of Guy’s assistants with the Collegians was Phil Tabor, coach of the East Liberty Academy baseball team. At Guy’s insistence, George enrolled at East Liberty to complete his high school education.

Upon graduation, George was accepted at the Staunton Military Academy, where he was a player-coach on the school’s baseball team. With restrictions on amateur players being quite lax, Edward pitched one game for Charleroi in the Penn West League in 1907. In the fall of that year he played with a team from Clearfield, Pennsylvania. Author Gerald Tomlinson noted in a 1983 article in SABR’s Baseball Research Journal that George played professionally under assumed names, including George Miller, from 1906 through 1908. Tomlinson surmised that George was protecting his amateur status while earning money for his college tuition.

Information on George’s scholastic career is sparse. According to school records, he enrolled at Washington and Lee University in the spring of 1908 to pursue a law degree. Rumors soon began to circulate throughout the campus implying that Edward was being financially compensated for his work on the diamond. In order to quell the rumor, a group of students, known as the Committee on Physical Culture, called for Edward, along with the management and coach of the baseball team, to sign a document stating that he wasn’t being paid by anyone associated with the ballclub. The committee requested that George enroll in a certain amount of classes in order to retain his baseball eligibility. The formal affidavit was signed by all involved, allowing the club’s star pitcher to rejoin the squad. George remained in good standing with the university throughout the year.

Around this time the press began referring to him as Lefty. The Richmond Times Dispatch, wrote, “He is a lefthander and is said to be one of the best pitchers in the south. In all of the games he has pitched, Lefty George has proven himself to be a slab artist of the highest order.” 2 The Washington and Lee baseball team finished out the 1908 college season with a record of 6-8-1.

That summer George returned home to Lawrenceville, pitching for the Collegians as well as the Millvalle club in the semi-professional Tri-Borough League. During this time the Pittsburgh Press reported that the National League Boston Doves had purchased the rights to Lefty’s contract. However, he doesn’t seem to have ever reported to the team.

When 1909 rolled around, George was back in Virginia pitching for the Staunton Military Academy. On March 27, he struck out 14 batters in Staunton’s 2-0 loss to William and Mary on the opening day of the season. George left the Staunton team a short time later to embark on his professional baseball career. The Trenton Tigers of the Class B Tri-State League paid $300 to the Boston Doves, who held the rights to Lefty’s contract, in order to obtain George for the upcoming season. Baseball-Reference.com shows Lefty pitching four games (0-3) for the Montgomery Climbers in the Class A Southern Association before reporting to Trenton in early June. Upon his arrival, the Tigers immediately traded him to the York White Roses, members of the same league, for pitcher Ray Topham. Accordingly, he never threw a pitch for Trenton.

Lefty (6-20) logged 246 innings for a York team that finished in last place in 1909. The Tri-State League operated under a $2000-per-month team salary cap as well as a $175 limit on each player’s salary with the captain of the team receiving $200. In the off-season, George refused to sign unless he was given an extra $25 in his monthly paycheck. Word of Lefty’s availability traveled as far as the West Coast with the San Francisco Seals of the Class A Pacific Coast League expressing an interest in him. George eventually reported to York although no evidence from contemporary newspaper sources indicates that he ever received his raise.

Back in York in 1910, George (12-20) was the workhorse (249 innings) for a team destined for another dismal finish. Throughout the season ivory hunters from the majors and high minors were hot on Lefty’s trail. On July 29, W.H. “Watty” Watkins, manager of the Indianapolis Indians of the Class A American Association, came to York to secure Lefty’s services. At the same time scouts from the Brooklyn Dodgers, Philadelphia Athletics, Detroit Tigers and St. Louis Browns were en route to York to entice Lefty to sign with their clubs. When they arrived in York they learned that George had already inked a deal with Indianapolis. Newspaper accounts of the day vary as to the actual monetary amount York received from the Indians, inferring that it was somewhere between $2,200 and $3,500.3 George was allowed to finish out the year with York before reporting to Indianapolis in September. On August 13, 1910, Lefty’s 24th birthday, he tossed a 1-0 no-hitter against the Harrisburg Senators at the York Fairgrounds.

George threatened to hold out for a percentage of his purchase price before eventually reporting to Indianapolis in early September. After watching him pitch, Joe Cantillon manager of the Minneapolis Millers, told The Sporting Life, “Lefty George has the making of the best left-handed pitcher in the profession.” 4

After George posted a 7-3 mark for Indianapolis, the American League St. Louis Browns picked him up in the draft for $1,000. A tough negotiator, Lefty mailed back two contracts to Browns president Robert Hedges before finally accepting the club’s third offer.

On February 7, 1911, Lefty married Mabel Rebecca Sipe in York. The couple would eventually have two boys and three girls.

The 6’0”, 155-pound George made his major-league debut on April 14, 1911, losing to Cleveland 7-5. Lefty struggled with his control for most of the season, going 4-9 with 51 walks in 116 1/3 innings. In Richard Guy’s article in the Pittsburgh Gazette Times, George confided to his discoverer and former mentor, “I have to depend upon my fastball almost entirely this year. My arm is good and I can get something on my fastball but the hook does not respond like it used to.” 5

At the American League winter meetings in Chicago, Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith offered catcher John Henry to St. Louis in exchange for George. Browns management turned down the deal. A short time later Lefty, requesting another raise in salary, refused to sign the contract sent to him by the Browns management. Tiring of his contractual demands, St. Louis traded George to the Cleveland Naps on February 17, 1912, for first baseman George Stovall.

Lefty dropped his first five decisions in 1912, leading Cleveland to farm him out to the Toledo Mud Hens, their minor league affiliate in the American Association. George seemed to regain his form with Toledo, finishing the year with a 10-7 record.

Lefty stayed on with the Mud Hens in 1913, going 16-20. In January 1914 George, who had threatened to jump to the Federal League if he didn’t receive a raise in salary, signed a three-year deal with Toledo worth $7,800. A few weeks later the Mud Hens sold him to the Cleveland Bearcats of the American Association, where he ended up with a 13-18 record.

In February 1915 the Bearcats dealt George to their inter-league rival, the Kansas City Cowboys. Lefty was not happy with the deal, claiming his contract allowed him to have the final say on where he would play. He eventually reported to the Cowboys but was let go in late July after refusing to accept a pay cut, presumably for his 3-6 mark. George moved on to the New Orleans Pelicans in the Class A Southern League, where he appeared in 7 games before signing with the Cincinnati Reds in early September. On September 11 Lefty shut out Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson and the New York Giants 4-0. Years later George reminisced about a conversation he had with Mathewson the following afternoon: “Matty congratulated me on my fine game the day before. He also showed me how to throw his fadeaway, now called a screwball.” 6 George appeared in five games for the Reds in 1915, achieving a 2-2 record with a 3.86 earned run average.

On March 18, 1916, George filed suit against Kansas City for money that he alleged was owed to him by the club. Lefty claimed that the three-year deal he signed with Toledo in January of 1914 carried over with the other teams he played with during the term of the contract. He won the lawsuit in February 1918, receiving $2,242 in back pay.

Lefty went on to play for the Columbus Senators in the American Association from 1916 until July 1918 when the league folded due to lack of attendance brought on by America’s involvement in World War I. He did relatively well with the Senators: 12-15 in 1916, 19-14 in 1917, and 11-9 before the league shut down in 1918. A few weeks after the Association folded George signed with the National League Boston Braves. He closed out the season with Boston, compiling an unimpressive 1-5 record. This was his last stint in the majors, finishing with a lifetime mark of 7-21 to go along with a 3.85 earned run average.

The start of the 1919 campaign found Lefty back with Columbus, where he won 20 and lost 15. He remained with the Senators until he was put on waivers in September 1920. Lefty was picked up by the Minneapolis Millers. His combined record for 1920 was a lackluster 12-19. The Millers released him the following year despite his going 10-8.

Lefty, who now resided in York, began pursuing other interests, including starting his own cigar business. In February 1922, he signed with the American Chain and Cable Company baseball team in York, an independent aggregation whose roster was laden with former professional players. The team competed in the Philadelphia Twilight League in addition to taking on a variety of other independent ballclubs. Because he was voluntarily retired from organized baseball, we have no record for Lefty in 1922.

When George returned to organized ball in 1923, the New York-Pennsylvania League was reorganized as a Class B minor league. The American Chain and Cable Company team changed its name to the White Roses, becoming York’s entry into the new loop. George set the record for strikeouts (162) to go with a 19-10 mark in the circuit’s fledgling season.

The following year, he pitched 45 scoreless innings, notched 16 straight victories, while pacing the circuit with 25 wins against only 8 losses. In 1925 Lefty led the league again with 27 victories and a 2.27 earned run average. He won two more times in the postseason as York defeated Williamsport three games to one in the playoffs.

George had another good year in 1926, with a 17-14 slate accompanied by a 1.95 ERA. His work over the next few years was solid, his win totals ranging from 11 to 20 and no losing seasons. He fell to 5-7 in 1933, no bargain but not bad for a 46-year-old.

From 1923 through 1933 George pitched in 330 games for York, winning 165 games and losing 98. During this time Lefty would occasionally travel to Baltimore in the fall to play with Joe Cambria’s Bugle Coat & Apron team or to barnstorm with other ballclubs made up of minor- and major-league all-stars.

George also tried his hand at politics, running unsuccessfully for York’s Republican seat in the Pennsylvania Legislature in 1930. In 1939 he switched parties, winning the Democratic primary but losing in the general election for a position on the York City Council.

The White Roses dropped out of the New York-Penn League after the 1933 season due to financial difficulties. For the remainder of the 1930s Lefty pitched for amateur and semi- pro teams in the York area. During the summer of 1940 professional baseball came calling once again. That season, York was the National League Boston Bees affiliate in the Class B Interstate League. York Bees skipper Rudy Hulswitt, Lefty’s manager with Columbus back in 1916, asked his former pitcher to toss batting practice to his team. The veteran portsider had so much stuff, Hulswitt sent word to Boston Bees president Bob Quinn that he wanted to sign the 54-year-old. Soon after Hulswitt got the green light from Quinn. Lefty joined the York team in August, going 3-2 in 42 innings of work. He allowed 51 hits, 7 walks, 15 runs while striking out 15 batters.

In March 1941 the Bees transferred their Interstate League franchise from York to Bridgeport, Connecticut. Bees secretary John Quinn, Bob’s son, told the press that he and his father appreciated Lefty’s good work the previous year. However, they were releasing him from his contractual obligations in case he wanted to catch on with another team. Not wishing to extend his professional career any further, George contented himself by playing sandlot ball on the weekends.

In 1943 the Harrisburg Senators, the Pittsburgh Pirates’ farm club in the Interstate League, relocated to York. Lefty, who was working as a salesman for the Capitol Beverage Company, was named to the team’s Board of Directors. That summer the United States was heavily engaged in World War II. The wartime draft caused a shortage of ballplayers. Teams at every level of organized baseball were forced to use men that had yet to be drafted or were too young or too old for military service. The limited player pool also included men that were classified as 4-F due to health issues as well as combat veterans who had returned home from the war. Lefty’s two sons, Thomas Jr. age 24 and John W. age 18, were serving in the Army at this time.

As the 1943 season progressed, the York team, renamed the White Roses, was in dire need of pitching. The club’s business manager Johnny Gordon and player-manager Johnny Griffiths turned to a couple of oldtimers for help. Gordon ran into Lefty George one day and asked him, “Do you think you can throw the ball over the plate Grandpop?” The soon to be 57-year-old replied, “Who are you kidding son” 7 as he hurried home to get his glove and spikes. Griffiths also contacted 42-year-old former major league pitcher Charles “Dutch” Schesler, who was working as the Sergeant of the Guard at the Harrisburg Steel Corporation. Schesler last pitched professionally in 1941. Both men agreed to terms with the White Roses and joined the team. Lefty’s full-time job with the Capitol Beverage Company didn’t permit him to travel with the club, so he only suited up when the White Roses were playing at home.

On June 2 Lefty was called upon to stop a rally by the Allentown Fleetwings in the seventh inning with a man on and one out. The Sporting News noted that over 600 of Lefty’s friends and neighbors were in the stands at West Park. The home crowd gave a rousing cheer as the 56-year-old Lefty trotted in from the bullpen. George retired the first two men he faced to end the inning, receiving another thunderous ovation as he walked off the field. Lefty was pulled in the next frame after giving up three singles. Schesler came in and closed out the game, preserving the 8-6 victory.

Two days later George came in to get the last out of a 15-8 victory over Allentown. On June 8, he pitched well in a ten-inning 3-2 win over the Lancaster Red Roses.

On June 16 George received his first starting assignment, tossing a three-hit 1-0 shutout against Lancaster in the first game of a doubleheader. He defeated Lancaster again on June 20, 6-3. George earned another victory in relief against the Red Roses on June 22. He lost his next two starts before allowing only six hits in a 4-3 win against the Hagerstown Owls on July 5. He went on to defeat the Owls again on July 15, 3-2. Three days later Lefty was tagged with the loss in the first tilt of a doubleheader against Lancaster. One consolation in this defeat was that George and teammate Joe Narieka combined to stop future Hall of Famer George Kell’s 32-game hitting streak.

White Roses business manager Johnny Gordon told Don Basenfelder of The Sporting News: “We figured a couple of veterans like George and Schesler would be good insurance to have around if only for relief roles. George looked so good rescuing our young pitchers that Griffiths rewarded him with starting assignments and he has been holding up his end despite the fact that he is almost sixty.” 8

Lefty’s good showing culminated in his being named the starting pitcher in the Interstate League all-star game held in Wilmington, Delaware, on August 9, 1943. George, pitching for the West squad, allowed one hit while tossing two scoreless innings. A good hitter throughout his career, Lefty stroked a double in a game that the East All-Stars eventually won 3-2.

George didn’t have much left on his fastball as he approached age 57, but he was able to get hitters out with a variety of slow sweeping curves released at various arm angles. He also had a screwball and knuckleball in his repertoire. The Ottawa Citizen observed, “His knuckler seems to flap wings as it comes floating up to the dish.” 9

Very few runners stole on George. Some were so fooled by his deceptive delivery they dove back to the first base bag as he released the ball towards home plate. Lefty credited New York Giants southpaw pitcher Hooks Wiltse with teaching him how to hold runners on at first base. Wiltse also taught George how to throw a change-of-pace, now called a changeup in modern parlance.

When asked by The Sporting News how he was able to pitch so competitively at his age, Lefty replied, “When you know where to put the ball you don’t need speed. When you’re young and dumb you like to throw fastballs and show how strong you are. Then as you grow older your high hard one loses it zip and you begin to get some sense.” 10

George appeared in 21 games for York in 1943, going 7-8 with a 4.71 earned run average. After pitching in only two games the following season, Lefty hung up his spikes for good on May 27, 1944, telling the Associated Press, “Guess I’m getting too old to pitch. I’ll step aside and let some of the younger fellows take over.”11 Lefty finished his minor-league career with a record of 327-287 and a 3.17 earned run average. This prodigious compilation of lifetime statistics doesn’t include the seasons Lefty played under assumed names or the hundreds of amateur, semi-pro and exhibition games he pitched during his five decades in baseball. In a series of articles published in the York Dispatch from August 5-13, 1954, George told sports writer Myles Loucks that he remembered throwing at least five no-hitters over the course of his career.

In the years that followed George remained an iconic figure in his adopted hometown of York. After a 21-day hospital stay in 1953, Lefty’s health began to worsen. On May 13, 1955, Thomas Edward “Lefty” George died from sclerosis of the liver at his home at 36 North Beaver Street in York. He was survived by his wife, Mabel, who died in 1964, five children and five grandchildren. George is buried in Prospect Hill Cemetery in York. In 1974 he was elected to the York Area Sports Hall of Fame.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Baseball-reference.com

Familysearch.org

Gulden, Dave. “The Legend of Lefty George” http://oldyorktimes.com/2013/09/07/the-legend-of-lefty-george/, posted on September 7, 2013, accessed October 26, 2013.

Johnson, Lloyd, ed. The Minor League Register. Durham, NC: Baseball America, Inc., 1994.

Library of Congress

Loucks, Myles. “The York Dispatch Presents: 50 Years In Baseball With Lefty George,” (York: Manufactures Association, 1954).

McClure, Jim. “Baseball’s Methuselah Played For York White Roses,” yorkblog.com/yorktownsquare/2007/06/18/baseballs-methuselah-played-fo/ posted June 18, 2007, accessed July 4, 2014.

Tomlinson, Gerald. “Lefty George, the Durable Duke of York,” Baseball Research Journal (Cleveland, SABR, 1983).

Newspapers

Baltimore Afro-American

Baltimore Sun

Baseball Magazine

Chicago Eagle

Daytona Beach Morning Journal

Eugene (Oregon) Register-Guard

Gettysburg Compiler

Gettysburg Times

Milwaukee Journal

New York Times

Ottawa Citizen

Palm Beach Post

Pittsburgh Gazette Times

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Pittsburgh Press

Reading Eagle

Richmond Times Dispatch

Sarasota Herald-Tribune

The Ring-Tum Phi (Washington and Lee University school newspaper).

The Sporting Life

The Sporting News

Washington Times

York Dispatch

Special Thanks

Lisa McCown, Senior Special Collections Assistant, Leyburn Library, Washington and Lee University, Lexington,VA.

Ida Joiner, Carnegie Library, Pittsburgh, PA.

Suzanne Johnston, Carnegie Library. Pittsburgh, PA.

Joyce Strong, Guthrie Memorial Library, Hanover, PA.

Linda Wolfe, Guthrie Memorial Library, Hanover, PA.

Frank Russo (DeadballEra.com) for providing Lefty George’s cause of death.

Reed Howard.

Notes

1 “Lefty George Comes Back For More After 35 years,” Associated Press, Quote excerpted from the Daytona Beach Morning Journal, August 17, 1940.2.

2 “W & Lee Leaves For Games In The North,” The Richmond Times Dispatch, May 05, 1908, 7.

3 The September 10, 1910, edition of the Sporting Life shows the sale price as $2,200. The February 24, 1911, edition of the Sporting Life lists the amount at $2,500. The August 6, 1954, edition of the York Daily Record gives a $3,500 purchase price.

4 Sporting Life, September 10, 1910, 17.

5 Richard Guy, “Ballclubs are Quitting,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, September 17,1911,19.

6 Sam Levy, “Greatest of the Iron Men,” Milwaukee Journal, May 21, 1955.

7 Don Basenfelder, “Grandpop George Grooving ’Em for York at 57,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1943, 5.

8 Ibid.

9 Harry Grayson.“ Grandpa Wins Regularly in Interstate Loop at Age 57,” Ottawa Citizen, July 3, 1943.11.

10 Don Basenfelder,“ Grandpop George Grooving ’Em for York at 57, The Sporting News, July 22, 1943, 5.

11 “Lefty George Quits Mound Duties at 58,” Associated Press, quote excerpted from the Palm Beach Post, May 28, 1944, 32.

Full Name

Thomas Edward George

Born

August 13, 1886 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

May 13, 1955 at York, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.