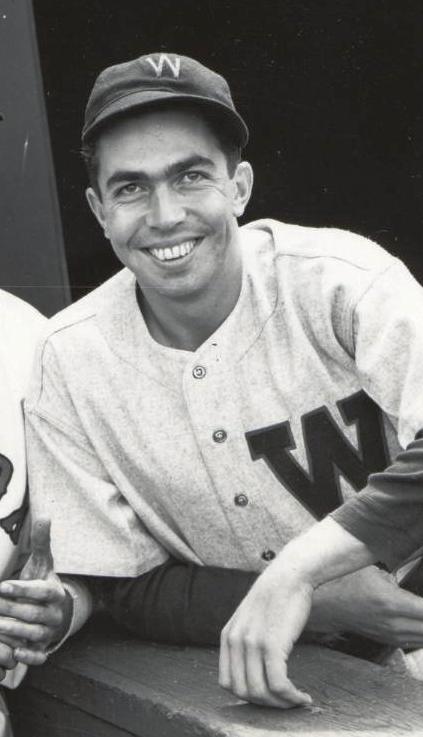

Mel Almada

Baldomero Almada — “Melo” or (to Americans) “Mel” — was the first native Mexican ever to play in the majors. Almada was born in Huatabampo in the state of Sonora on February 7, 1913, but he grew up in Los Angeles from an early age. On September 8, 1933, less than two months after a heavily Mexican crowd celebrated their favorite on “Melo Almada Day” at L.A.’s Wrigley Field, the outfielder debuted with the Boston Red Sox. He went on to bat .284 in 646 games with the Sox, Senators, Browns, and Brooklyn Dodgers across seven big-league seasons.

Baldomero Almada — “Melo” or (to Americans) “Mel” — was the first native Mexican ever to play in the majors. Almada was born in Huatabampo in the state of Sonora on February 7, 1913, but he grew up in Los Angeles from an early age. On September 8, 1933, less than two months after a heavily Mexican crowd celebrated their favorite on “Melo Almada Day” at L.A.’s Wrigley Field, the outfielder debuted with the Boston Red Sox. He went on to bat .284 in 646 games with the Sox, Senators, Browns, and Brooklyn Dodgers across seven big-league seasons.

Though Almada lacked power, he was a good contact hitter and base-stealer. He often led off, with a batting style that appears similar to Ichiro Suzuki’s many years later. Tommy Holmes, writing from Brooklyn in the July 6, 1939 Sporting News, called him the “most pronounced ‘water bucket’ hitter in the majors. You never saw a guy in such a hurry to keep a date at first base. He seems to be running towards the initial hassock even before his bat meets the ball.” Alas, Mel Almada never won a batting crown … despite his noble conquistador blood.

Baldomero Almada Quirós, who was named for his father, traced his paternal ancestry back centuries to Iberia. Washington sportswriter Shirley Povich recounted this history in the May 15, 1938 Washington Post. Don Álvaro Váz de Almada died in the 1449 battle of Alfarrobeira serving Don Pedro, the rebellious regent of Portugal — but not before being knighted in London by King Henry VI of England and designated Count of Abranches by King Charles III of France. One of Don Álvaro’s forebears, Don Antonio Vásquez de Almada, had served with valor in the battle of Aljubarrotta more than 200 years earlier, routing the Spanish from Portugal. And that’s not to mention Don Ruy Fernández de Almada, Don Cristóbal de Almada, Don Francisco de Almada, and Don Antonio, who fought to restore Portugal’s independence and became King John IV’s ambassador to England. There were several other Dons of note, and some Doñas as well.

It was Don Antonio’s son who expanded the family to Mexico. Melo’s great-grandfather was said to have owned a lucrative silver mine and enough acreage in Mexico that one could fit the country of Belgium within its boundaries. Shirley Povich reported that one of Mel’s uncles was “brutally butchered by the Yaqui Indians.” The forces of Pancho Villa imprisoned another uncle for a few months and confiscated the family properties. Mel’s great-grandfather had a sister who was to be married in the church across the street from the family abode, but the road was exceptionally muddy. Servants prepared to lay down some boards when the patron had bars of silver brought up from storage and laid across the road, making for the “most expensive road crossing in history.” [The Sporting News, September 5, 1935]

In Povich’s account, it was Mel’s great-great-grandfather, Don José María, who laid down the silver bars. The story delves into legend in several places, offering such tales as the 52 legitimate children fathered by Don José María and the time he fired an enemy’s pistol into his own chest to prove he was unafraid. A later Almada was said to have buried strongboxes of silver at various locations on his vast lands but was struck with cholera and died, unable to reveal the locations where the silver had been hidden.

The elder Baldomero Almada was a buyer for the Mexican government and supervised a string of ranches. In 1920, he was appointed governor of Baja California by President Álvaro Obregón, following the last throes of the Mexican Revolution. He had most recently worked as an exporter of “foodstuffs, cement, and mobile houses.” [Washington Post, June 3, 1920]

When Mel’s father arrived to take over as governor, incumbent Esteban Cantú simply refused to vacate the office. As Mel himself said, Cantú had “a large well-equipped army, while my father’s army consisted of my mother and eight children.” [The Sporting News, September 5, 1935]

Amelia Quirós, herself descended from a noble Spanish family, had another son named José Luis and six daughters (Amelia, Esther, Concepción, Aurora, Carmen, and Neli). [Los Angeles Times, June 3, 1920]

Melo told Harry Edwards of the American League Service Bureau that his father “decided his family would prefer the glorious climate of Los Angeles to the excitement of trying to oust the governor who refused to be ousted.” Several Almadas were killed by warring factions and it seemed like a good time to serve elsewhere. Baldomero was offered the position of Ambassador to France, but didn’t want to travel that far from his homeland. The consulate in New York would probably be too cold in the winters, he thought. He finally took the post of consul in Los Angeles. At one point, he also served for a stretch as commercial attaché in San Francisco for the Mexican government.

His son Melo had moved to southern California with his family at the age of one in 1914, amid the political and business turmoil of the Revolution. (The April 25, 1935 Hartford Courant said that Melo had left Mexico four weeks after he’d been born, but Mel himself said he was a year and a half old at the time. See The Sporting News, September 5, 1935.)

John Drohan of the Boston Traveler later wrote, “Had Carranza remained president of Mexico, Mel might have become a bullfighter or possibly just another deceased hero of the cause.”Melo learned baseball as a child playing on the sandlots of Los Angeles, as did his older brother José Luis (Americanized to Louis, “Louie”, or “Lou”). [The Sporting News, November 1, 1934]

Their father had become a passionate baseball fan and encouraged his sons to play the game. They attended Jefferson Grammar School, John Adams Junior High, and Los Angeles High School.Lou Almada played outfield for nine full years in the Pacific Coast League, spending 1929 through 1937 with Seattle and the Mission Reds. He turned pro with Albany of the Eastern League in 1927, the year before he joined the PCL, as a New York Giants pitching prospect.

Lou won his only decision, leaving him with an undefeated 1-0 pro record (he made very brief appearances as a pitcher in three other seasons). It must have been quite a game. Lou gave up 16 hits, walking two and striking out one. He might well have become the first Mexican big-leaguer that year. However, he was injured by a line drive off the bat of Fred Lindstrom during batting practice in spring training. Author Gilberto Garcia notes that Lou later got homesick and bolted Albany for home.

In 1928, he played one game with the Hollywood Stars.Melo Almada first made the Los Angeles Times as a halfback for the Los Angeles High Romans in September 1929. He earned his first headline on October 26, for a 53-yard touchdown run. He also excelled at track, at one point setting the southern California record for the running broad jump with a leap of 23 feet, 4 3/4 inches. (Late in his third season with the Red Sox, this led a Sporting News cartoonist to dub him a “Mexican jumping bean.”)

When City League baseball began in May 1930, L.A. High coach Herbert White gave the left-handed Almada the starting assignment. The Romans beat their archrivals from Polytechnic, 8-1, holding them to five hits; Melo contributed both a single and a home run in the team’s five-run sixth inning. Mel pitched throughout high school and played outfield. He also played American Legion ball with the William Lane Junior Legion Post and for a semipro team in the area named the El Pasos.

After Mel graduated from high school, he went to be with his brother, then playing with the Seattle Indians. Manager Ernie Johnson (later a scout with the Red Sox) spotted his potential, giving him a shot — but Johnson urged him to quit pitching and become an outfielder. Johnson told college-bound Melo that he’d be “crazy if he wasted his time on the so-called higher education.” [Collier’s, August 24, 1935]

Louis — also known as “Ladies Day Lou” for his success on those occasions — cost himself his job with Seattle in 1932. There was a good deal of publicity about the talented pair of brothers, both of whom had starred on the mound for L.A. High. Lou thought to bring Melo to Santa Cruz, where the Seattle team trained. The Times’ Bob Ray told readers back in Los Angeles that “Melo got a job with the Tribe and Louie, who was looking for a better salary package, was given the gate. Fortunately for Louie, though, he caught on with the Missions.” [Los Angeles Times, May 2, 1932] Louis was released in April [The Sporting News June 7, 1934].

Though originally intended as a utility outfielder, Melo played in 127 games for Seattle, hitting .311 in 438 at-bats, with six home runs. Those of Almada’s hometown fans arriving even a minute late for the start of the September 5 doubleheader missed out — he hit the first pitch of the game for a long home run. The Times writer honored Melo with a bit of melodramatic prose: “Many of the fans were still standing, but the concussion from this blow staggered them into their respective reserved seats, stupefied if not actually stunned.” [Los Angeles Times, September 6, 1932] Mel also stole 28 bases. [The Sporting News, December 21, 1933] Louis did even better with the bat in 1932, hitting .320 for the San Francisco Missions.

Even in March 1933, Melo was being touted as perhaps the “best young outfield prospect” in the Coast League. [The Sporting News, March 23, 1933] He started the season strongly. Playing left field again with Seattle, he led off with a double and hit safely four more times for a 5-for-5 day on April 8 in L.A. He had four-hit games on May 7, June 10, and June 20 as well, and a 17-game hitting streak from May 28 to June 11. Under a headline VIVA ALMADA!, it was already being predicted that the 20-year-old would be sold to a major league club before the season was out.

Indeed, Eddie Collins signed him for the Red Sox on July 2, acquiring Almada from Seattle as part of a reported $40,000 transaction also involving the 1932 PCL home run champion, second baseman Freddie Muller. It was one of owner Tom Yawkey’s early deals — he’d only purchased the ballclub at the end of February. The Sporting News wrote in December that the transaction had saved the Seattle club “from financial ruin.” [December 14, 1933]

The Sox left Almada with Seattle for further seasoning. Meanwhile, Muller fizzled out quickly. He debuted on July 8, but only got into 15 games, made five errors, hit zero home runs, and batted just .188. After two 1934 at-bats without a hit, his days in the major leagues were complete.

On July 23, “Melo Almada Day” at Wrigley Field took place. Mexican consul Alejandro V. Martínez and Rosita Moreno, the “beautiful Mexican screen actress of the Fox studios,” presented him with a gold baseball. A photograph of Moreno and Almada was headlined “Thees for You, Senor”. [Los Angeles Times, July 24, 1933] The golden ball was a gift from what the paper called the “Mexican colony of Angeles”. Boxers Kid Azteca and Baby Face Casanova also made appearances. Bob Ray wrote of Almada’s tribute, “He’s a dandy chap and deserves it.” Almada was 2-for-7 on the day, but Seattle lost both games to the Hollywood Sheiks.

Almada made his big-league debut on September 8, 1933. He played center field and led off in both games of a Fenway doubleheader against Detroit, going 1-for-4 in each game. He hit his only home run of his first season off New York’s Herb Pennock on September 23. Mel had replaced Smead Jolley during a 16-12 slugfest, and he scored three of Boston’s dozen runs. The left-handed outfielder batted .341 in 14 games before the end of the season, with three RBIs. He played a few games at first base as well, plus left field in an exhibition game against the Braves near the end of the month.

It was a sign of the era in which he played that Collier’s described him as a “radio nut” and said “He even carries a portable radio with him on baseball trips, plugging it into his hotel room and listening to the programs.” One of the reasons he finished with such a good average was that he batted against Babe Ruth in the last game the Babe ever pitched, the October 1 game that ended the season. In Yankee Stadium, Ruth gave up 12 hits — 25% of them to Almada, who drove in one run. But Ruth also homered and earned the win in the 6-5 game.

At the time of his debut, the Los Angeles Times had noted that Almada was the third Mexican ballplayer to play in the major leagues. The prior two were born in the United States. One fact the newspaper did not note: all three played for the Boston Red Sox. The Sox had previously fielded pitchers Frank Arellanes and Charley Hall (who pitched for the Red Sox from 1909 through 1913). Would that the Red Sox had pioneered in the signing of African American ballplayers as well!

During the offseason, Melo played in a few exhibition games in the Los Angeles area, including one against Satchel Paige and the Philadelphia Royal Giants and another with a group of all-stars against the USC Trojans. The Portland All-Stars traveled to Mexico to play 13 exhibition games against Mexican ballclubs. Portland owner Roy Mack was impressed with the quality of play and said, “I understand that the Almada brothers will soon come to Mexico to advise the Mexican leagues and their visit undoubtedly will result in a better kind of baseball being played in this country and a better knowledge of the game by the Mexican players.” [The Sporting News, November 30, 1933]

Lou Almada had made the PCL All-Star team, but was seeking more money. He almost quit the Missions to take an offer to teach baseball and coach in Mexico City, but perhaps things worked out better for him. In any event, he elected to stay and hit very well, batting .332.

Mel Almada’s averages were up and down in Boston. He batted .233 in 23 games in 1934, .290 as a regular in 1935 (607 at-bats in 151 games), and .253 in 1936 (as a semi-regular, appearing in 96 games). The 1934 Red Sox, entering their first full year under new owner Tom Yawkey, began to build a farm system. They developed working relationships with the New England League club in Worcester and the American Association’s Kansas City Blues. The only club the Red Sox owned was in Reading. On January 10, the Red Sox exercised a $10,000 option they held on Almada; three days later, he was optioned to Kansas City. [Los Angeles Times, January 14, 1934]

He played excellent ball, made the All-Star team and won the club’s MVP award over the course of 135 games, thanks in good part to his .328 average and 30 stolen bases. Near the end of the year, Boston (under manager Bucky Harris) recalled Mel, and he drove in another 10 runs. The “Spaniard” had two of the three hits the Sox mustered against Detroit’s Elden Auker on September 10. The “Spanish recruit” (again, the Atlanta Constitution) singled and scored the lone run in the September 12 1-0 win against the Tigers. After his first 36 games, he’d only committed one error in the field.

In 1935, Mel went to his first spring training with the big league team and came out strong. Paul Shannon of the Boston Post wrote that “by his brilliant showing [Almada] has seemingly earned his right to the center field berth.” [The Sporting News, April 18, 1935]

Mel stuck with the big league team, missing just three games all year — and truly starred in a May 16 exhibition game in Syracuse. The Sox beat the Chiefs, 10-6, largely on the strength of Almada’s two-run double in the sixth and grand slam in the seventh. He impressed throughout the early going; in fact, The Sporting News praised him to the rooftops in its May 30 issue: “Mel Almada, now justly regarded as the greatest outfielder Boston has known since the days of the renowned Tris Speaker, is constantly confirming predictions that he will be one of the real stars of the season.” Mel’s .290 mark included three homers and 59 RBIs, plus nine triples, and he stole 20 bases.

After the season, he played some Winter League ball in the L.A. area, where he lived with his parents.

The Sox added Heinie Manush in 1936 and he won about the same playing time as Almada and Dusty Cooke (all had 300-odd at-bats). Doc Cramer was the only true regular. It was a deeper outfield, but Mel’s hitting dropped off, first in spring training — which gave Cooke an early leg up — and then again later in the season. Manager Joe Cronin sat Mel down in September, with Jimmie Foxx taking over for some 16 games in the outfield. The club was a bit fractious, as temperamental Wes Ferrell was fined and Billy Werber clashed with Cronin more than once. Mel hit one homer and drove in 21. In the winter, he played some more ball in Los Angeles and also spent some time hunting deer in northern Mexico.

Manush was released near the end of the ’36 season, and Cooke spent 1937 with Minneapolis. Buster Mills joined Cramer as a regular outfielder; Fabian Gaffke got most of the replacement work, but Dom Dallessandro and Almada did their parts as well. The Red Sox — who’d featured the only Danish-born big-leaguer, Olaf Henriksen, from 1911-17 — were cosmopolitan for the time. At points that season, their roster included Almada (who spoke Spanish), Gaffke (German), Dallesandro (Italian), and Gene Desautels (French). Multilingual catcher Moe Berg could converse with each.

Mel was beaned in an April 13 exhibition game and suffered a concussion. Not long after he came back, he was asked to fill in four days for Foxx at first. Mills was not hitting well initially, so Mel took over for him for an early stretch. Yet he still wasn’t being used as much, and became part of a large June 11 trade with Washington. Both Ferrell brothers were swapped to the Washington Senators, with Mel, for Ben Chapman and Buck Newsom. Joe Cronin was happy to rid himself of Wes Ferrell, and Senators skipper Bucky Harris was glad to see the last of Newsom — and to welcome Almada. Dan Daniel’s summary of Mel’s career at the time of the trade? “He falls short of being a really good ball player, but these days you can’t be too choosy.” [The Sporting News, June 17, 1937]

Mel played out 1937 with the Senators and really boosted his batting: he’d been hitting .236 for Boston, but hit .309 for Washington over the final 100 games. Though he helped the Senators snap a Yankees winning streak on July 2 with a four-hit game, his standout day was the July 25 doubleheader in St. Louis. Mel scored four runs in the first game and five in the second; overall, he was 6-for-9 at the plate, with a home run in the first game and a double in both. The downside was his two errors in the first game, but Washington swept the twin bill, 16-10 and 15-5.

Apparently, Mel joined the Ferrell brothers playing string music on the road. Wes played electric guitar; what Mel played wasn’t clear. The three shared an apartment in the District and hired a cook to prepare their meals. [See the Shirley Povich column in the June 2 Washington Post and Charlie Casper’s article, “Melo of Mexico” in the December 1938 issue of Baseball.]

Almada’s work for Washington was “a revelation to Washington fandom and even his employers.” He was one of the few Senators to get a raise for 1938. [The Sporting News, December 30, 1937] The euphoria didn’t last long, though. Almost a year to the day, he was swapped again — on June 15, 1938, to St. Louis for outfielder Sam West. Browns fans wondered why. Again starting the season slowly, Almada was hitting a soft .244 at the time of the trade. He had particular trouble hitting left-handers. “I’ve always been a slow starter,” he said, ‘because I’m always trying to get started off on the right foot. I guess I kinda get tense and all tied up when I’m trying to hit in that first month or six weeks and just mess everything up, but once I get started, I usually finish up pretty good.” [Casper, “Melo of Mexico”, Baseball, December 1938]

West was hitting .309 and had hit .328 the year before. The Browns knew he was 10 years older, and felt Almada was a better fit for their needs.

There’d been a little excitement during spring training when Almada hit a home run, and later shouted something off the bench to Cardinals catcher Mickey Owen about the pitches to his head. The two had known each other since their L. A. sandlot days. Owen charged the Washington bench and the two grappled with each other on the ground for a few minutes before being ejected. Though Melo’s flashy outfield work won him a strong following among the fans, Harris had given up on him as a force on offense, even disliking his batting stance. “When he swung, he had nothing behind his stroke,” wrote the D.C. correspondent in the June 23 Sporting News. Shirley Povich said a few months later that he’d become “a colossal joke as a hitter” — before the trade. [Washington Post, August 16, 1938]

The change of scenery seemed to help once more. Mel batted .342 for the Browns, helped considerably by a 29-game hitting streak. His total of 197 base hits set a mark for Mexican big-leaguers that would not be surpassed until 1998, when Vinny Castilla got 206 for the Colorado Rockies. Only George McQuinn hit as well for St. Louis in 1938. Washington was satisfied with Sammy West, too. It was one of those trades that worked out for both parties.

Melo claimed that his hitting streak was broken during the season “because John Hanley, Browns’ clubhouse attendant, failed to bring his daily letter from his loved one back in California.” [Casper, “Melo of Mexico”, Baseball, December 1938] The romance bloomed, though, and after the season was over, Melo departed quickly south of the border and on October 30 he married the former Alicia Terminel in Navojoa, Sonora. [Los Angeles Times, November 1, 1938]In 1939, for the third year in a row, Almada was moved in mid-June. St. Louis sold him to the Brooklyn Dodgers for $25,000. This time Mel’s average went down instead of up, from .239 to .214. He didn’t seem to have it anymore. It hadn’t started out that way — he earned a subhead “ALMADA STARS” in the March 6 Atlanta Constitution; the Associated Press saw him as a “strong contender for the regular centerfield post” with the Dodgers.

Mel traveled north with Brooklyn out of spring training but saw no early season action. His last at-bat in a major league uniform was a pinch-hitting appearance in the April 14 exhibition game against the Yankees in New York; he grounded into a double play. A couple of weeks into the season, manager Leo Durocher made a decision, selling him to Rochester on April 24 when the roster was cut down. Durocher reportedly “didn’t have the heart” to tell him, so he ducked out a side door and left it to Brooklyn’s traveling secretary to inform Almada. That probably didn’t make Mel feel any better — he refused to report and “disappeared from view”. [The Sporting News, May 2 and May 23, 1940]

Though he was still only 26 years old, Mel Almada’s career in the majors had ended. Despite his solid .284 lifetime average, his lack of power (.367 slugging percentage) was his biggest drawback. He’d driven in 197 runs but scored 363. He always had a good arm in the outfield and racked up 47 assists.

SABR researcher Carlos Bauer asked Lou Almada why his brother’s career had ended so early. Lou answered, “Melo couldn’t stand being thrown at. ‘Louie,’ he once said to me, ‘They’re throwing at me because I’m a Mexican!’ ‘No, Melo,’ I told him, ‘They’re throwing at you because you’re a batter!’”Bauer added, “Melo, on the other hand, became obsessed with the notion that pitchers had it in for Mexicans — or him personally. Had he played today, I’m sure he would have been at least a near Hall of Famer. But then was then, and now is now. Pete Coscarart, who played with Melo, told me that the moment one pitcher found out that Melo could be intimidated by a brushback pitch, every pitcher in the league began throwing at him like there was no tomorrow.”

Mel then returned home to southern California — but he wasn’t quite done playing. First he appealed to Commissioner Landis, asking that he be declared a free agent so he could have a shot at signing with another major league team. Landis asked the Dodgers to offer him on waivers again, but after no one claimed him, his contract became Rochester property. The Red Wings worked out a deal with the Sacramento Solons, and Almada officially came on option to the PCL club on May 15. He didn’t do well, batting .232 in 306 at-bats with just a pair of homers.

The next year, Almada played as a pro in his native Mexico for the only time. He served as player-manager for Unión Laguna (Torreón), going .343-0-18 in 26 games. However, he gave up the post and quit playing on May 16. Among other things, Almada had difficulty controlling hard-hitting — and hard-drinking — third baseman Roy “El Indio” Arkeketa, an Oklahoman from the Ponca tribe. Headhunting by opposing pitchers may also have helped drive him from the league, suggested his friend and teammate, pitcher-outfielder Manolo Fortes. Mexican author Dr. Jaime Cervantes Pérez interviewed the Cuban, then aged 90, in 2004.

Fortes recalled that the black players in the Mexican League hated Melo because he had played in the major leagues. In addition, Fortes described Almada as “un hombre alto blanco” — or “high white,” not only depicting the man but also implying resentment of his station in society. The beanballs began in Monterrey and spread from there; Almada asked the front office to step down, and Fortes was informed that he was the new manager.

Almada then headed back north of the border once again. Even during his time with the Red Sox, the handsome young man had gotten some work in Hollywood. Brother Louis had a position with Warner Bros., and Mel was cast in several movies, mostly Mexican releases for Warners and Fox. In a December 8, 1935 press release from the American League, he explained, “They give me a small speaking part occasionally.”

After organized baseball, he still picked up a bat once in a while; a March 23, 1942 snippet in the L. A. Times noted that he drove across the lone run in 1-0 win for the Arcadia Merchants over the Kenna Dome Wildcats. Semipro ball was never going to cover expenses, though. He worked in the produce business for some time, but — still being young — served in the U. S. Army during World War II. He joined the Army Medical Corps in 1944, training at Camp Barkeley in Texas. During 1945, Almada played for the Fort Sam Houston Rangers ball team in the San Antonio Service League. He batted .303 and also pitched and won five games for the Rangers.

Some years after the war, Almada spent two-plus winters as manager of the Navojoa Mayos, a Sonora-based entry in the Mexican Pacific Coast League. According to the Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano, Melo was in charge for the 1953-54 and 1955-56 seasons, plus part of 1956-57.

In 1973, he was one of 11 notable figures named by a special committee for the opening induction of the Salón de la Fama in Monterrey, the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame. In the early 1980s, Almada lived in Tucson. He told Arizona Daily Star writer Keith Rosenblum that he’d never experienced discrimination in baseball — but he qualified that by adding, “Humiliation? Yes. Every so often, we’d be out for a drink and suddenly someone would say, ‘Hey, you goddamned Mexican…what makes you think you can act like an American?” [August 2, 1981]

Almada had four children: Miguel, born in Mexico, and Eduardo, Lydia, and Cecilia. Eddie Almada is a bilingual baseball broadcaster for the Liga Mexicana del Pacífico and a columnist with his own web page at www.pasandolabola.com. He’s done television work for the Diamondbacks and for TELEVISA, and he works as a consultant for some teams as well. He’s proud to exclaim, “Baseball is my life!”

Mel Almada died of a heart ailment on August 13, 1988 in Caborca, Sonora. Brother Lou survived him until 2005. Mel is still remembered in Mexico; even today its Pacific League awards the Baldomero Almada trophy to its rookie of the year.

Acknowledements

Thanks to Peter Mancuso and Rob Neyer for providing articles from Baseball, and to Rory Costello for quite a few hits in the late innings, uncovering additional information during his peer review.

Sources

Email communications with Eddie Almada, March 2009.

Further genealogy and family information:

Pérez Quirós de Urrea, Petra and Roxana Hutchinson de Pérez-Quirós. “Pérez-Quirós Family” (http://www.geocities.com/genbuff2002/Page9.html).

Carlos Bauer’s talk with Louie Almada can be found at: http://minorleagueresearcher.blogspot.com/2005_09_01_archive.html

Jaime Cervantes’ interview with Manolo Fortes can be found at:http://www.jaimecervantes.netfirms.com/EntrevistaManoloFortes%20II.htm

Garcia, Gilberto. “Beisboleros: Latin Americans and Baseball in the Northwest, 1914-1937.” Columbia magazine, Fall 2002.

Professional Baseball Player Database V6.0

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, editor, Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano. (Mexico City, Mexico: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V., 1998)

Bedingfield, Gary: Baseball in Wartime (http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/almada_mel.htm)

Photo Credit

Boston Red Sox

Full Name

Baldomero Melo Almada Quiros

Born

February 7, 1913 at Huatabampo, Sonora (Mexico)

Died

August 13, 1988 at Caborca, Sonora (Mexico)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.