Mary Dobkin: Baltimore’s Grande Dame of Baseball

This article was written by David Krell

This article was published in Spring 2024 Baseball Research Journal

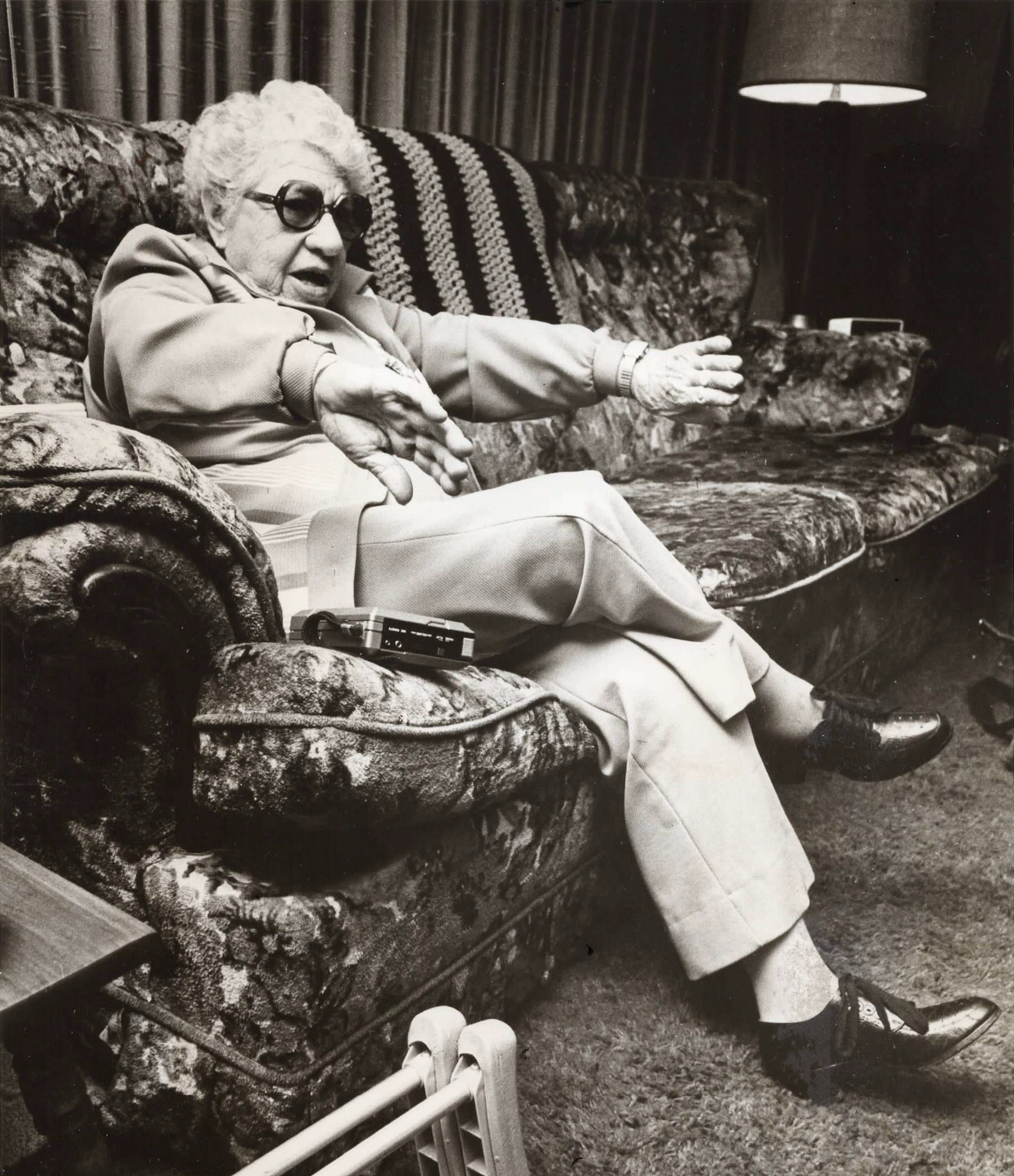

Mary Dobkin at age 77, while speaking to the press about the TV movie “Aunt Mary.” (Historic Images)

Nineteen-seventy-nine was quite a year for Baltimore. The Orioles returned to the World Series for the first time in eight years and one of the city’s most impactful residents got well-deserved national recognition. Her name was Mary Dobkin. Aunt Mary. Nearing 80 years of age with spryness belying her declining physical condition—which included prosthetics because of the amputation of both feet and half of a leg—Dobkin stood in the box of Commissioner Bowie Kuhn at Memorial Stadium under a nighttime sky in mid-October. Baseball’s decision makers had bestowed upon her the honor of throwing out the ceremonial first pitch for Game Six of the World Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates.1

Doug DeCinces, the home team’s third baseman, was her battery mate. Though not a nationally known VIP, Dobkin was baseball royalty in Chesapeake Bay’s environs; she created teams for kids who wanted to play baseball but otherwise wouldn’t have had the opportunity.

Dobkin’s story is heartbreaking, which makes her resilience even more inspiring. When she and her parents came from Russia to America, her mother left the family and her father died. An aunt and uncle, already with five kids, took Mary in and they moved to Baltimore. The family either never went looking for her or gave up too soon when 6-year-old Mary wandered the streets during a cold night, suffering frostbite and a loss of consciousness.

A Good Samaritan took Mary to the hospital. Speaking only Russian, and with severe physical challenges, which eventually led to her amputations, Mary was never reclaimed by her aunt and uncle. She became a ward of the city and lived at the Johns Hopkins Hospital until she was in her late 30s. But her spirit would not be quashed by her lifelong problems, which the frostbite had triggered. “By all known rules, I should have died,” she said. “If God was good enough to let me live, I made up my mind that I would work with children for the rest of my life.”2

Mary learned English through radio broadcasts and newspapers, which is a familiar tale for twentieth-century immigrants. Baseball was both an outlet and a salve. “Then one summer she got to attend therapy camp,” reads a 1979 Los Angeles Times profile. “From her wheelchair, she was taught to catch and hit a baseball. It was magic. Quiet, reclusive Mary Dobkin returned to the hospital a new person, ignited by direct experience with baseball.”3

She combined her dedication to kids and love of baseball in the early 1940s.4

Baltimore’s leading newspaper, the Sun, reported on Dobkin being more than an organizer when one of her teams got selected to play at Memorial Stadium in 1954. It was part of an Interfaith Night sponsored by B’nai B’rith, Knights of Columbus, and the Boumi Temple Shrine. She was a coach. “Miss Mary goes out to the ball field and directs some of the teams some nights, either from her wheelchair or on her crutches or from the aluminum beach chair her boys bought her,” the Sun reported.5

Dobkin learned the fundamentals of baseball from TV broadcasts of Orioles games and often hosted kids at her apartment to join her in this endeavor. Neither her sex nor her infirmity, marked by 110 operations, were an issue in gaining their confidence. “The boys themselves wanted me to manage their team and never once have they made reference to the fact that I’m a woman doing what normally is a man’s job,” she said.6

Her efforts impressed local merchants and the business community, who launched the Dobkin Children’s Fund. Donations included “many thousands of dollars’ worth of sports equipment and facilities.” The number of boys in Dobkin’s operation was estimated to be “about 200” in 1958.7

That year, Dobkin was honored by the TV show End of the Rainbow, described on IMDb as a show that ran in 1957–58, with co-hosts Bob Barker and Art Baker going across America and surprising “the less-fortunate who helped others when they could barely help themselves.” Dobkin’s bounty included uniforms and equipment for her teams in baseball, basketball, and football along with a television and $1,000 for the Mary Dobkin Children’s Fund.

The program had an emotional wallop for the woman who represented toughness, perseverance, and encouragement for Baltimore’s kids. She shared a promise that she’d made during her own childhood: “If God is good enough to let me live to be a grown-up, I’ll devote my whole life to helping children.”8

But Dobkin’s appearance did not happen solely because of the production staff. The board members of the children’s fund had written letters advocating for Dobkin to be a guest on This Is Your Life, a 30-minute show that usually focused on the lives of celebrities. Ralph Edwards produced both shows. The board never heard back about This Is Your Life but did hear from End of the Rainbow.9

No less an authority than the Baltimore Police Department certified Dobkin’s impact on the community. Captain Millard B. Horton said, “We all recognize that there is a juvenile problem in these underprivileged areas, but Miss Dobkin is one of the few people who really went out and did something about solving it.”10

Don Gamber was one of the kids who played for Dobkin. “Mary was friends with the crossing guard, Miss Helen, and she used to ask her to take us to the Fifth Regiment Armory to see the Ringling Brothers Circus every year,” recalls Gamber, a pitcher and outfielder on Dobkin’s teams. “One time, she called my mom and said, ‘Pat, can I take your boys for a surprise?’ She brought me, my brother John, my cousin Danny, and some other neighborhood kids to Memorial Stadium to throw a surprise birthday party for Bubba Smith after a Colts practice.

“Mary was selfless and she loved the kids. She didn’t take any crap. Other managers didn’t like her. She argued with umps. There were certain kids that she got close with. I was one. She knew that I had a lot of talent with baseball and football and introduced me to Bob Davidson, owner of a Ford dealership on York Road. He got me involved in Ford Punt Pass and Kick competitions. Mary got me tryouts with the Orioles, Pirates, and Reds.”11

At the beginning of 1960, a front-page story appeared in the Evening Sun describing the questionable future of the fund. Even with donations, Dobkin didn’t have the means to pay rent for the clubhouse at 1323 Harford Avenue.12

Moved by Dobkin’s efforts, some people paid for newspaper ads asking for contributions. In March, Samuel Stofberg and Stanley Stofberg sponsored an announcement revealing that the donations had allowed the fund to pay for part of the clubhouse but more would be needed to pay each month; the fund didn’t own it outright.13

Through donations inspired in part by personal newspaper advertisements, Dobkin got enough to start another clubhouse in the Armistead Gardens neighborhood. It was sorely needed. Dobkin’s efforts gave kids an outlet that protected them from submitting to self-destructive activities. When an adult saw some kids wearing her team’s uniforms and asked her whether they had a game, Dobkin said, “Those kids are wearing my uniforms because they don’t have anything else to wear to school.”14

The consistent goodwill toward Dobkin and the kids she supervised did not go unnoticed. In January 1964, she wrote a letter to the editor of the Evening Sun highlighting the generosity of the holiday season reflected in parties held by the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute’s junior class and faculty members; Toys for Tots donations from the US Marine Corps First Engineer Battalion; and the American Sokol-Club and St. Francis Xavier Church giving space for parties. “We hope members of our community will continue to help us with our year-round program for underprivileged children as long as the need exists,” she wrote.15

In March, the Evening Sun ran a feature story that allowed her to dispel a misperception about the donations, which included a block of 500 tickets to a Baltimore Bullets basketball game. “Whenever I get publicity, it seems that people get the notion that we’re rich and have all we need,” said Dobkin. “That just isn’t the case. In September we were broke.”16

Dobkin also ran a softball team for girls called Dobkin’s Dolls.17

In 1966, a banquet honoring her 25 years of generosity drew luminaries including Rocky Marciano, Johnny Unitas, Brooks Robinson, Dave McNally, Jim Palmer, Steve Barber, and announcer Chuck Thompson, who served as the toastmaster. Robinson said what the people in Chesapeake Bay’s environs had known since the early 1940s: “Mary Dobkin can’t be repaid in full for the wonderful work she has done in Baltimore.” Unitas noted her impact as well: “The work Mary has done has cut down juvenile delinquency and I hope there will be many more Mary Dobkins.”18

In 1973, Dobkin was part of a group of two dozen Baltimore citizens honored during the City Fair for being “Special Baltimoreans.” They were selected by a committee from “among several hundred nominations…for outstanding contributions to the quality of city life.”19

Dobkin’s life became the basis for Aunt Mary, a 1979 Hallmark Hall of Fame movie starring Jean Stapleton. It aired on CBS on December 5, about seven weeks after Dobkin’s moment in the World Series spotlight. Harold Gould and Martin Balsam had supporting roles. According to the Baltimore News-American, watching Aunt Mary was part of a homework assignment for “thousands of Baltimore school children,” along with reading a copy of the script.20

Jay Mazzone, a former Dobkin player who was a batboy during the Orioles’ 1966–71 heyday, perhaps best represented Aunt Mary’s determination because of a similar situation—doctors amputated his hands after his snowsuit caught fire when he was 2 years old. In Aunt Mary, Tim Gemelli plays an amputee whom Dobkin recruits; Gemelli didn’t have a right hand at birth.21

At the time that the TV movie was in production, Dobkin had endured 155 operations.22

She recalled that her involvement with underprivileged kids began when she realized they didn’t have equipment that other kids had. East Baltimore wasn’t Pikesville or Reisterstown, after all. So she organized a raffle for a radio. Once the kids had an outlet for their restlessness, the streets were quieter. The merchants calmer. Amos Jones owned a food joint called the Dog House and praised Dobkin because there were no more break-ins, so he decided to buy uniforms for Dobkin’s Dynamites.23

Jones’s tale was one of several represented in the movie. Dobkin provided color commentary during the broadcast for Sun writer Michael Wentzel, who watched it in her East Baltimore apartment along with some of her friends. The events portrayed were steeped in fact. “That is for real,” Dobkin would say. “She would say it often during the film,” Wentzel wrote. A rock crashing through the glass in Dobkin’s living-room window. Dobkin blowing a whistle into the phone when she gets obscene phone calls. The tough kid named Nicholas.24

Many of the players kept in touch with their guidepost through adulthood, including Nicholas. “The real one stopped in earlier to say hello,” Dobkin said on the night of the broadcast. “He’s an engineer now.”25

Aunt Mary condenses the real story into a 1954–55 setting and emphasizes the pioneering aspect of her coaching. A key scene involves Dobkin subtly threatening a racist sporting goods store owner to provide a uniform for a Black player on her team, lest Tommy the Torch, a neighborhood arsonist, use his skills. Racial integration on Dobkin’s teams happened in 1955. Aunt Mary ends with her bringing a girl on the team; she actually busted the gender line in 1960.26

New York Times TV critic John J. O’Connor praised Stapleton’s portrayal as “an effective blend of compassion and toughness.”27 O’Connor’s counterpart at the Boston Globe, Robert A. McLean, was equally positive: “The best part is that Aunt Mary is for real, and it’s her life story that Stapleton portrays with depth and dignity and a fine flair for humor in the face of adversity.”28

The Sun’s Michael Hill also endorsed this story of Baltimore’s grande dame of baseball. After praising Stapleton’s performance, he wrote: “Indeed, the strength of ‘Aunt Mary’ is its near-perfect casting. Martin Balsam is his usual fine self as the across-the-hall neighbor, Dolph Sweet is perfect as the impresario of A.J.’s Dog House, the team’s sponsor, and even the kids, normally stumbling blocks in films like this, are quite believable.”29

Sun TV critic Bill Carter concurred: “[Stapleton] is an actress of intelligence; she knows how to cut through the schmaltz to the basics,” he wrote.30

Stapleton recalled meeting Dobkin early in the shooting of the movie in Los Angeles, though the Baltimore icon didn’t stay around to see the entire production. “She had a great PR talent,” Stapleton said. “She was always looking for publicity for the team and herself. She was a great lady.”31

Indeed, she was. Dobkin’s legacy lasted through generations. “But my greatest joy is the boys who are now grown up and are bringing their own kids to practice,” she said in a profile for the Sun. “Some of them are my best coaches.”32

By 1982, Dobkin was estimated to have undergone 180 operations.33 Her building—3899 in the Claremont Homes public housing complex located at 3885–4047 Sinclair Lane in East Baltimore—was a long-time destination for generations of kids to visit, whether after a game or to say hi to the woman known as Aunt Mary. After suffering a stroke, Dobkin lived in Levindale Hebrew Geriatric Center and Hospital’s nursing home section for the last months of her life.34

Mary Dobkin died on August 22, 1987. Her obituary was a front-page story for the Sun. Former Orioles manager Earl Weaver said, “Just to see the look on the kids’ faces when they had Mary Dobkin Night at the stadium and they’d present her with a trophy was special. She touched a lot of lives.”35

There is a baseball field named after Dobkin in East Baltimore. Given her selfless devotion to the Orioles and the city, there ought to be a statue of her at Camden Yards and an annual night dedicated to her where the O’s wear uniforms with the Dobkin’s Dynamites logo.

DAVID KRELL is the chair of SABR’s Elysian Fields Chapter. He has written four books: Our Bums: The Brooklyn Dodgers in History, Memory and Popular Culture , 1962: Baseball and America in the Time of JFK , Do You Believe in Magic? Baseball and America in the Groundbreaking Year of 1966 , and The Fenway Effect: A Cultural History of the Boston Red Sox.

Acknowledgments

I want to highlight the invaluable assistance of Margaret Gers in the Periodicals Department at the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore. Margaret provided several archival articles from the Baltimore Sun and Baltimore News-American in addition to biographical information about Mary Dobkin.

Notes

1 The Pirates were down 3–1, then battled back to win the World Series in seven games.

2 Beth Ann Krier, “Aunt Mary: Still Going to Bat for Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, June 1, 1979, E1.

3 Krier.

4 “Mary Dobkin Honored Tonight,” Baltimore Sun, December 11, 1966, A2.

5 “Miss Mary’s Baseball Teams To Go ‘Big League’ At Stadium,” Baltimore Sun, June 21, 1954, 28.

6 “Miss Mary’s Baseball Teams”; Thomas McNelis, “‘Aunt Mary’ Lone Woman Pilot Here,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 27, 1954, 51.

7 “Club House Appeal Made,” Baltimore Sun, May 9, 1958, 8.

8 “Look and Listen with Donald Kirkley,” Baltimore Sun, January 20, 1958, 8; “End of the Rainbow,” Internet Movie Database, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt13159768/; “John Crosby’s Radio and Television,” Baltimore Sun, January 22, 1958, 34.

9 Hope Pantell, “To View,” Baltimore Evening Sun, January 28, 1958, 20.

10 “Club House Appeal Made,” Baltimore Sun, May 9, 1958, 8.

11 Don Gamber, telephone interview, March 2, 2022.

12 Travis Kidd, “Aunt Mary Dobkin’s Hopes Fade,” Baltimore Evening Sun, January 14, 1960, 1.

13 Newspaper ad, Baltimore Sun, March 6, 1960, 46.

14 Travis Kidd, “Aunt Mary Dobkin Overcomes Setbacks in Providing Aid,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 24, 1960, 25.

15 “The Forum: Letters to the Editor—Thanks from Mary Dobkin,” Baltimore Evening Sun, January 23, 1964, A12.

16 Robin Frames, “Aunt Mary Brings Cheer To Many Young Lives,” Baltimore Evening Sun, March 10, 1964, B1.

17 Irvin Nathan, “Piloting Cubs No Problem To Veteran Mary Dobkin,” Baltimore Evening Sun, July 29, 1964, D4.

18 Jim Elliot, “Tribute Is Paid To Mary Dobkin,” Baltimore Sun, December 12, 1966, C1.

19 Josephine Novak, “‘Special Baltimoreans’ Being Cited For Contributions To Life Quality,” Baltimore Evening Sun, September 19, 1973, C1.

20 Peggy Cunningham, “Aunt Mary,” Baltimore News-American, December 5, 1979, 1C.

21 Cunningham.

22 Krier, “Aunt Mary: Still Going to Bat for Baseball.”

23 Isaac Rehert, “Mary Dobkin, baseball coach on crutches, to get ‘Bunker’ treatment in Hollywood,” Baltimore Sun, April 10, 1979, B1.

24 Michael Wentzel, “‘This is all real,’ says ‘Aunt Mary’ as she watches ‘repeat’ at home,” Baltimore Evening Sun, December 6, 1979, A1.

25 Wentzel.

26 Michael Hill, “‘Aunt Mary,’” Baltimore Evening Sun, December 5, 1979, B1

27 John J. O’Connor, “TV: Jean Stapleton as Manager of a Baseball Team,” The New York Times, December 5, 1979, C29.

28 Robert A. McLean, “‘Aunt Mary’ just couldn’t miss,” Boston Globe, December 4, 1979, 47.

29 Hill, “‘Aunt Mary.’”

30 Bill Carter, “Aunt Mary’s TV hometown: Baltimore shot in L.A.,” Baltimore Sun, December 5, 1979, B1.

31 Karen Herman, “Jean Stapleton discusses the TV movie ‘Aunt Mary,’” Television Academy Foundation Interviews, November 13, 2015. Interview conducted November 28, 2000, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vuZ9Vke_JE (accessed January 24, 2023).

32 Rehert, “Mary Dobkin, baseball coach on crutches.”

33 Morton I. Katz, “Aunt Mary: 80 Years Young,” Baltimore Sun, October 9, 1982, A11.

34 Margaret Gers, personal conversation, February 7, 2023. The city of Baltimore demolished the complex in 2004.

35 Rafael Alvarez, “Cronies recall ‘Hot Rod Mary’ and her love for life,” Baltimore Sun, August 24, 1987, 1A.

JEAN STAPLETON: HOW EDITH BUNKER BECAME AUNT MARY

When Jean Stapleton took on the role of Mary Dobkin for the TV movie Aunt Mary, she didn’t set out to do an impersonation.

“I’m not trying to imitate her but to catch her spirit,” said Stapleton, the winner of four Emmy Awards and two Golden Globe Awards during the glorious nine-year run of All in the Family. “I’m trying to perceive her thinking; I’m watching her pace. I’m searching for her motivations because that’s where you have to start.”1

Aunt Mary had initially been a project for Hallmark and NBC, but it fell through. Ellis Cohen, an alumnus of Dobkin’s teams who provided the story for Aunt Mary said, “So she’s been boycotting Hallmark for the past year and a half.”2 Hallmark Hall of Fame moved from NBC to CBS in 1979.

Burt Prelutsky wrote the script and Peter Werner directed.

“I’m a businessman, so to a certain extent you’re drawn because you think you can sell it,” producer Michael Jaffe said. “But once we had it sold and I had a chance to talk with Aunt Mary herself and meet some of the people associated with her and get the movie cast, then it became interesting. Peter did a great job in capturing the humor. This was his second movie. Jean was wonderful, gracious, cooperative, hard-working, and sweet. A perfect human being. Dolph Sweet was one of the great character actors of all time. The story was funny where it needed to be funny and serious where it needed to be serious.”3

Aunt Mary was Stapleton’s first TV production after All in the Family, which ended in 1979, and her appearances in five episodes of its spinoff, Archie Bunker’s Place, which began airing that fall. Lucille Ball had expressed an interest in playing Dobkin. Show business columnist Cecil Smith mentioned it as part of a 1977 Los Angeles Times feature about the iconic comedian: “There are other roles Lucille Ball itches to play—a legless legend of a woman who has been a patron saint of the ghetto kids of Baltimore, for one.”4

Werner, the director, doesn’t seem to have been bothered that that didn’t work out. “From the moment I met Jean,” he said, “she was interested in my ideas and wanted to rehearse. I loved that kind of preparation. We continued to have a personal friendship.”

Of course, the movie also featured what Werner called “a bunch of young actors.”

“The most challenging part was directing the ‘cute’ out of them,” he said. “I studied the Bowery Boys movies, which had street type kids.”5

Robbie Rist was one of those young actors. Best known for his six-episode stint as Cousin Oliver in the last season of The Brady Bunch, Rist recalled, “Peter made an effort for us to be a team, a unit. Mary came to the set a couple of times. I think aside from it being a very sweet movie, we need more Mary Dobkins in the world. We need more people who care. We need more people who have souls. All of us kids were aware of the fact, somehow, of what she brought to the world.

“I think it was an acting choice on Jean Stapleton’s part that she took on the same maternal role off camera. She was super cool and close with everybody. A true character actor.”6

Anthony Cafiso and his brother Steven played brothers Nicholas and Tony in Aunt Mary. “Mary Dobkin came to the set in a wheelchair,” Anthony said. “She was very quiet, very humble. She had a face of awe, almost in shock that said, ‘This is all about me.’ Later on, I could only imagine what she must have felt like after what she went through in her life and what ended up being the effect of it.

“I went to see Jean in Nyack, New York, when she played Eleanor Roosevelt in a one-woman show. This was the early 1990s. I brought flowers and asked one of the theater workers after the show to tell her who I was. She wanted to see me. It was like seeing my aunt. She always made time for us.”7

Michael Hill of the Sun wrote, “Ms. Stapleton is the perfect choice to play this working-class hero. There’s a lot of Edith Bunker there, and a lot of Jean Stapleton.”8

Notes

1 Kay Mills, “Aunt Mary story filmed in Calif.,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 1, 1979, C1.

2 Michael Hill, “‘Aunt Mary,’” Baltimore Evening Sun, December 5, 1979, B1.

3 Michael Jaffe, telephone interview, December 28, 2022.

4 Cecil Smith, “They Still Love Lucy,” Los Angeles Times, May 23, 1977, 79.

5 Peter Werner, telephone interview, March 7, 2022.

6 Robbie Rist, telephone interview, February 3, 2023.

7 Telephone interview with Robbie Rist, February 3, 2023.

8 Hill, “‘Aunt Mary.’”