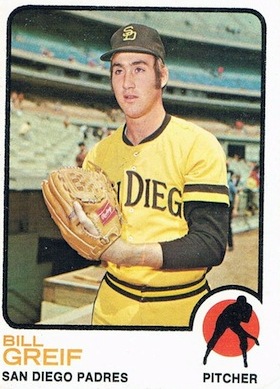

Bill Greif

In the months leading up to his graduation from high school in 1968, Bill Greif, a 6’5″, 200-pound, multi-sport athlete, was in demand. He starred in track and field, started on the basketball team, led the football team to a state championship as the starting quarterback. As a pitcher he had been attracting baseball scouts to his games for three years. He had countless scholarship offers to play college athletics. Living in the football-crazed state of Texas, Greif felt the lure of legendary Longhorns’ football coach, Darrel Royal. “I had signed to play college football at the University of Texas,” Greif said in an interview with the author.1

In the months leading up to his graduation from high school in 1968, Bill Greif, a 6’5″, 200-pound, multi-sport athlete, was in demand. He starred in track and field, started on the basketball team, led the football team to a state championship as the starting quarterback. As a pitcher he had been attracting baseball scouts to his games for three years. He had countless scholarship offers to play college athletics. Living in the football-crazed state of Texas, Greif felt the lure of legendary Longhorns’ football coach, Darrel Royal. “I had signed to play college football at the University of Texas,” Greif said in an interview with the author.1

But just as his high school days ended, the fourth annual Major League draft took place. With all the attention he’d received, Greif recalled, “I expected to be drafted. But it was a surprise who did and what round.” Excited to discover that the only team in Texas, the Houston Astros, had drafted him in the third round, he retracted his letter of intent to play football, and began his professional baseball career just a few weeks later.

William Briley Greif was born on April 25, 1950, in Fort Stockton in western Texas to Doc and Marian Greif. Because his father was a civil engineer who coordinated construction projects throughout the state, the family moved around quite a bit; however, baseball was a constant in the family’s life. The second of four children, Bill began to play organized baseball by the age of 8, and a year later, in little league, he recognized his ability to throw a baseball. Then living in the Snyder area of central Texas, Greif’s coach was a former semi-pro baseball player, Mut Thompson. “He was an inspiration,” Greif said, “and helped me with mechanics. He had a concept of how to throw a pitch.”

A natural athlete, Greif excelled as a shortstop, but pitching was his passion. “I didn’t try to model myself after any pitcher,” he remembered. He added, with a sense of humor, “I used to spend a lot of time wishing I was left handed so I could be like Warren Spahn.” His baseball career took off during his sophomore year at Arlington High School in Arlington, Texas, where he was coached by Eddy Peach. Just 16 years old, but with an overpowering fastball and an overhand curve, Greif began to attract the attention of scouts who followed him from the Dallas area to Austin, where he pitched his last two years at John H. Reagan High School.

After he was drafted in June 1968, Greif recalled, “I received a phone call, then the Astros sent a representative, Stan Hollmig, who represented the Astros in negotiations.” Although his family was very supportive of his decision to pursue baseball, Grief noted, “[I]n my family, academics were a high priority. I anticipated going to college whether I signed to play baseball or not. It was an agreement between my folks and me that I’d pursue a degree.” Throughout most of his career in the major and minor leagues, Greif attended college in the offseason, earned his B.A., and was also enrolled in graduate programs.

Greif signed a contract with the Astros at the end of his senior year in high school, and was assigned to the team’s Rookie Class affiliate in the Appalachian League, the Covington (Virginia) Astros. After four years living near Dallas and Austin, Grief found himself in a small town in the Appalachian Mountains. “It was a big come down in terms of where I had been and where I ended up,” Greif said, “but I was extremely excited to play professional baseball.” He immediately noticed the quality of coaching and the attention to pitching on the team, which also included a 17-year old Cesar Cedeno. “I was hungry,” Greif said, “and would talk to anyone about pitching.” He leaned especially on his Cuban-born manager, Tony Pacheco.

Having impressed the Astros with his 2.84 ERA in 76 innings in Covington, Greif was promoted to the team’s Class-A Peninsula Astros in the Carolina League the following season. However, he missed spring training and a month of the season because he was still enrolled in college. Ultimately, he suffered a season-ending arm injury after just pitching 30 innings.2 “I got a start against the Kingston Eagles. I started out throwing well, throwing strikes,” Greif said. “In the third inning I was trying to throw harder than ever and I popped my elbow. It was an audible sound. When it popped, it hurt, [but then] I thought it was OK. . . The next morning I woke up with my elbow as big as my leg.” It was the first injury of his career, but it did not require surgery. He rested, and then played in the Arizona Fall League while studying at Arizona State University.

Despite missing most of the season, Greif received some good news. “I was put on the major league roster after the 1969 year,” Greif recalled, “and that was one of the finest things that ever happened to me. I was feeling sorry for myself because of my arm. Then I got notice in the mail that I was to report to the Astros spring training and was on the major league roster.” As a 19-year-old in his first spring training with the Astros in Cocoa Beach, Florida, he was in awe of the players, many of whom he had cheered for and whose baseball cards he had collected. “My greatest thrill may have been being in the club house one day,” Greif reminisced about his first spring training playing at Cocoa Expo Stadium. “I am looking around and I see Jimmie Wynn, Joe Morgan, Larry Dierker, and Don Wilson. I had to pinch myself to make sure it was really me.” He roomed with Larry Yount, another highly touted, 19-year-old pitcher. Despite some good outings, Greif learned from general manager Spec Richardson that he was optioned to the Double-A Columbus (Georgia) Astros in the Southern League.

With only 17 professional starts and 106 innings under his belt, Greif needed some additional experience. Columbus had a strong starting rotation, and Greif was considered the Astros’ third best pitching prospect in the minor league system, behind Ken Forsch and Buddy Harris, both of whom played for Columbus. The team won the league pennant.3 Used exclusively as a starter, Greif bounced back from his injury, posted a 2.89 ERA in 190 innings, but was a hard-luck loser with a 10-12 record. “Greif has a dandy arm,” said Tal Smith, the Astros’ personnel director.4

Back at the Astros’ spring training in 1971, Greif was used primarily in relief, and it appeared he would make the team. Much to his disappointment, he was the last player cut, and he was optioned to the club’s Triple-A affiliate, the Oklahoma City 89ers in the American Association. “When I started pitching for Oklahoma City, I was a little disappointed because I was in Triple A and not in the majors,” Greif recalled. “But it was a good year. We had a very strong pitching staff.”

Indeed they did. All five of the Astros top pitching prospects — J.R. Richard, Scipio Spinks, Harris, Yount, and Greif — played for 89ers manager Jimmy Williams that year. Though sporting an unimpressive 5-8 record, Greif was called up to the Astros in mid-July, on the strength of recent strong outings. He filled a roster spot vacated by Bob Watson, who was fulfilling his military reserve duty.5

Starting against the Phillies on July 19 in Houston, Greif made his major league debut in front of family and friends. He pitched 6 1/3 innings, struck out six, and gave up just two runs in a no-decision.6 He was shelled in his next start, and was lifted in the first inning after allowing all four batters he faced to reach base. His first major league victory came on September 24, when he pitched 1 2/3 innings in the major’s longest game of the season, a 21-inning contest against the Padres. Once Bob Watson returned in early August, Greif was sent back to Oklahoma City, but he returned to the Astros in September, when the team expanded its roster.

During the baseball winter meetings in 1971, the Astros traded Bill Greif, pitcher Mark Schaeffer and infielder Derrel Thomas to the San Diego Padres for pitcher Dave Roberts. “The trade was a complete surprise,” Greif recalled. “I hadn’t even considered that as a possibility. I guess I was naive about what could happen.” Though he was disappointed about leaving Houston, Greif decided that, “it was a big opportunity. I got to go to a ball club that was struggling and I knew that I would have the opportunity to compete for a job.” The Padres expected Greif to join a young starting rotation that included Steve Arlin, Clay Kirby, and Fred Norman. “Greif has good stuff and keeps the ball down,” said Padres president Buzzie Bavasi. “There’s no reason he shouldn’t develop into a winner.”7

In his Padres debut on April 16, in the third game of the 1972 season, Greif pitched a masterful six-hit shutout over the Atlanta Braves, striking out eight for his first win as a starting pitcher. After three erratic starts, and losses, he beat Tom Seaver in a nationally televised game on May 6, and then evened his record at three wins and three losses by beating the Expos in his sixth start.

And then the bottom fell out. Coming off a 100-loss season in 1971, the Padres, a very weak hitting team, were even worse in 1972, batting just .227 for the entire season. Pitching inconsistently, Greif lost his next seven starts; the Padres scored just eight runs total in those games. Relegated to the bullpen, Greif blew a save opportunity for his eighth consecutive loss, dropping his record to 3-11.

Just 22 years old, Greif was accustomed to winning his entire life, no matter what sport he played; he took the losses personally. “I pretty much collapsed under the pressure of losing. I had never encountered that kind of losing. I ended up internalizing it and blaming myself.” He finally won his fourth game of the season in a spot start on July 9, against the Phillies, and fought his way back into the starting rotation. However, Greif’s confidence in himself and his teammates was still smarting. Before the end of the 1972 season, after losing another five consecutive starts, “they took me out of the rotation to make sure that I would not lose 20 games.” Greif ended the season with only five wins, and his 16 losses were second most in the league. His 5.60 ERA (in 125 1/3 innings) was the highest in the league for all pitchers with at least 20 starts.

Greif stressed that working with Padres pitching coach, Roger Craig, in 1972 helped him for the remainder of his career. “Roger was an excellent tactician,” Greif said. “We talked a lot about setting pitches up and which pitch to throw in each situation. It was situational pitching and that was very helpful for me.” Craig understood the art of pitching, but also the psychological effects of losing. He had lost 24 and 22 games for the Mets, in 1962 and 1963, respectively, and in the latter season lost 18 consecutive decisions. Greif said that Craig gave him confidence to pitch despite the losses.

Notwithstanding a good spring training, Greif started 1973 in the bullpen. Given a spot start in the second game of a double header on April 15, he tossed a two-hit shutout against his former team, the Astros. He walked with bases loaded in the fifth inning for his first and only career RBI. The performance helped pave his way back into the starting rotation.

Greif recalled that the key to his success was a pitch he’d never thrown in a major league game before. “I started throwing a knuckleball when I was in Little League,” Greif said. “In 1971, in Triple A, I began to use it as a pitch and had good luck with it. The pitch I threw was a little unusual. It was a knuckleball in that I intended to take all of the spin off the ball, but rather than throwing it as a lesser speed pitch, I threw it as hard as I could. I threw it overhand and at a speed not much different than my fastball. I called it a knuckle curve because Burt Hooten had had some success with the pitch.” The Astros had discouraged him from using the pitch and wanted him to concentrate on his fastball and curve and develop a slider, but in San Diego he resurrected the pitch with his catcher, Fred Kendall, in spring training. Kendall was impressed with the movement of the ball in Greif’s shutout. “I knew this spring that the umpires would think Bill’s knuckler was a spitter,” he said. “I made a point of telling them, but they still checked the ball once in a while.”8

It appeared as though Greif had found his pitching rhythm. After shutting out the Mets and Jerry Koosman on June 1, Grief’s record was just 4-5, but all his victories were complete games and his ERA was a stellar 2.05. Then, in almost a repeat performance from the previous year, Greif lost his next seven starts, although he kept his spot in the rotation. As the losses accumulated for Greif, the Padres were on their way to another 100-loss season. “I felt responsible for all of the losing,” Greif recollected. “I’d try to tighten up the game and do something extra, but at a certain point, it became counterproductive. I got to the point that I didn’t expect anything good to happen.” Despite his frustrations, Greif was the Padres’ most consistent and effective pitcher that season. His third shutout, another two-hit masterpiece on August 8 against the Phillies, lasted just 90 minutes; it was the fastest nine-inning game in Padres history at the time.9 Referred to as the “hard luck member of the staff,” Greif finished with a career-high 10 wins, though his 17 losses ranked third in the league.10 More impressive was his above average 3.21 ERA in 199 1/3 innings.

The 1973 offseason was a turbulent one for the San Diego Padres. It appeared as if owner C. Arnholt Smith would sell the team to a Washington, D.C. grocery chain owner, Joseph Danzansky, who pledged to relocate the team to the national’s capital (Washington had lost the Senators just two years earlier). However, Smith changed his mind and sold the team to McDonalds’ founder, Ray Kroc. The uncertainty surrounding ownership over the previous 18 months had been unsettling for the players. “Things were strained last year,” Greif said. “It affected every aspect of the team.”11

But with the wealthy Kroc willing to spend money on veteran players to improve the team’s hitting, Greif saw a positive forecast for 1974. “There won’t be the distraction of not knowing from one day to the next whether the team is staying or going. Those things will improve your morale.”12 Kroc brought in former all-stars and other top players, such Willie McCovey, Glenn Beckert, Matty Alou, and Bobby Tolan, but all were well past their prime and failed to live up to expectations. John McNamara replaced Don Zimmer as manager, but the Padres replicated their previous season’s 60-102 record, and finished last in the NL West for the sixth consecutive year.

After another rough start to the season, losing three of his first four starts (in which the Padres scored just three runs), Greif registered his first win in a complete game against the high-powered Reds in Cincinnati. He then lost seven of his next eight decisions, dropping his record to 2-10, with an unsightly 5.58 ERA. However, he persevered on a team that struggled to hit. The Padres ranked last in the NL with a .229 batting average and .632 OPS. Over the second half of the season, Greif pitched much better. He twice won three consecutive decisions, and finished with a team-high (tied with three others) nine victories and 226 innings pitched. His 19 losses ranked fourth in the NL. Greif credited his second-half improvement to a new forkball, which rookie teammate Dan Spillner encouraged him to use in games.13

Remarking on Greif, Spillner (9-11), 22-year old rookie Dave Freisleben (9-14) and 24-year-old Randy Jones (8-22), Padres manager McNamara commented near the end of the season: “This season hasn’t been a washout mainly because of the progress made by our young starting pitchers.” He expected marked improvement in 1975.14

The Padres made a conscious decision to build the team around their young pitching staff. The team traded for Alan Foster, Sonny Siebert, and Rich Folkers; these new acquisitions, along with the 23-year old Joe McIntosh and the ’74 starting quartet, made no fewer than eight pitchers compete for spots in the starting rotation. McNamara and new pitching coach, Tom Morgan, who had worked with the Angels’ Nolan Ryan the previous three years, guaranteed no one a starting position.

Greif had another strong spring performance, and like the previous year he began the season in the bullpen. But in 1975 he was given just one spot start to work back into the starting rotation. The Padres used him consistently in short relief, and as their closer. He ranked among the league leaders in games pitched before trailing off the last month of the season. He pitched in a career-high 59 games, and tied Danny Frisella with the team lead of nine saves.

Greif was never afraid to pitch inside to great hitters or to protect his teammates. “I’ve always had a tendency to challenge hitters,” he said. “When I’m behind the count, I say ‘here, hit it if you can, I’m not going to walk you.’”15 He touched off two bench clearing brawls in the first half of the 1975 season after hitting Greg Luzinski of the Phillies and Willie Crawford of the Dodgers, which gave him a reputation as a “dirty” pitcher. “I don’t want to hurt anybody,” Greif said, “but if they are going to brush back our hitters, then I have to brush back theirs.”16

Having posted a record of 24-52 from 1972 to 1974, primarily as a member of the Padres’ starting rotation, Greif did not want to be a full-time reliever in 1975, and he fought the decision. He was just 25 years old and his health was excellent. When pitcher Joe McIntosh was traded in the off-season, Greif fully expected that he would rejoin the starting rotation, and so did manager McNamara.17

Greif was exceptional in spring training, and on the strength of a string of 13 scoreless innings in the Cactus League he was promoted to the starting rotation.18 But after beginning the 1976 season with five consecutive ineffective starts, in which he lasted just 22 1/3 innings and sported a 8.06 ERA, Greif was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals. Bing Devine, general manager of the Cardinals, coveted the big right-hander as a set-up man for his left-handed closer, Al Hrabosky.19 Greif started off well, and gave up just four hits and one earned run in his first 11 appearances. After the trade he appeared in more games (47) than any other Cardinals pitcher other than Hrabosky.

In light of that performance, Greif was shocked when the Cardinals traded him to the Montreal Expos in the offseason. “I didn’t want to be in the bullpen,” Greif said, “and frankly I didn’t want much to be in baseball.” He and his wife, Karen, his childhood sweetheart whom he’d married in 1971, had two children; one needed critical medical care at the time of the trade. With his attention on his family, baseball became less important, and he lost his passion to pitch. The Expos released him on March 30, 1977.

Greif believed his baseball career was over, and was excited to begin a new career in real estate. But when he watched games on television or read about them in the newspaper, Greif wondered if he had made the right decision. After all, he was just 27 years old, extremely healthy, and entering his physical prime. “The transition [to civilian life] was a big disappointment,” he recalled. He felt that he had failed, but the year away from baseball motivated him to try again. His wife, who worried that he would regret never trying to make it back to the Major Leagues, supported his comeback attempt. “I wrote a letter to all the clubs and general managers,” to express his desire to pitch.

The New York Mets, managed by Joe Torre, were coming off a 98-loss season, and decided to give Greif an opportunity. “All of our reports said he has a big-league arm and he never had arm trouble,” said Mets general manager Joe McDonald. “It was always intangibles, we felt, that kept him from being a winner.”20

Greif was invited to the Mets spring training, but suffered from shoulder injuries and fatigue aggravated by his year layoff. He was sent to the Tidewater Tides, the Mets Triple-A affiliate in the International League, to rehabilitate. But after just three appearances, including two starts, Greif realized he no longer had the ability or desire to pitch competitively. He was released and retired from baseball. He finished his Major League career with a 31-67 record, with a 4.41 ERA in 715 2/3 innings.

Upon his retirement from baseball, Greif and his family returned to Austin, Texas, where he was still living as of 2012. A successful realtor and investor, Greif’s formal relationship with baseball ended in 1978; he did not pursue coaching or scouting. “Having been a Major League player is a big part of my life,” Greif recalled in an interview with the author. “There were times I thought I would have been a 15-year veteran and pitched in some all-star games, but it didn’t happen that way. But I still have pride that I was able to wear the uniform.”

Last revised: April 25, 2014

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Notes

1The author would like to express his gratitude to Bill Greif ,who was interviewed on October 17, 2011. All quotations from Bill Greif are from this interview unless otherwise noted.

2 All season statistics have been verified on Baseball-Reference.com; http:// www.baseball-reference.com.

3 The Sporting News, August 15, 1970, 37.

4 The Sporting News, November 21, 1970, 48.

5 The Sporting News, August 31, 1971, 33.

6 All individual game statistics have been verified on Retrosheet; http:// www.retrosheet.org.

7 The Sporting News, March 4, 1972.

8 The Sporting News, May 5, 1973, 21.

9 The Sporting News, August 25, 1973, 20.

10 The Sporting News, October 13, 1973, 19.

11 The Sporting News, March 2, 1974, 32.

12 ibid.

13 The Sporting News, September 28, 1974, 19.

14 ibid.

15 The Sporting News, March 2, 1974, 32.

16 The Sporting News, July 19, 1975, 19

17 The Sporting News, December 27, 1975, 46.

18 The Sporting News, April 17, 1976, 15.

19 The Sporting News, June 5, 1976, 19.

20 The Sporting News, February 25, 1978, 48.

Full Name

William Briley Greif

Born

April 25, 1950 at Fort Stockton, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.