The 1996 Sun Super Major Series in Japan

This article was written by Blair Williams

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1960-2019

“I don’t know how else to feel,” Hideo Nomo said – almost sarcastically – to Japanese reporters following Game 2 of the 1996 Sun Super Major Series.1 A blue Dodgers cap adorned Nomo’s head, the intertwined letters “L” and “A” announcing the pitcher’s allegiance to the American powerhouse team. Japanese by birth and citizenship, Nomo was the first Japanese national to play in major-league baseball in 30 years.2 Now, he returned to Japan to face his former colleagues from Nippon Professional Baseball, the baseball league that he had voluntarily retired from to escape the decades-long labor dispute that prevented Japanese players from playing abroad.

“I don’t know how else to feel,” Hideo Nomo said – almost sarcastically – to Japanese reporters following Game 2 of the 1996 Sun Super Major Series.1 A blue Dodgers cap adorned Nomo’s head, the intertwined letters “L” and “A” announcing the pitcher’s allegiance to the American powerhouse team. Japanese by birth and citizenship, Nomo was the first Japanese national to play in major-league baseball in 30 years.2 Now, he returned to Japan to face his former colleagues from Nippon Professional Baseball, the baseball league that he had voluntarily retired from to escape the decades-long labor dispute that prevented Japanese players from playing abroad.

“The way I feel hasn’t changed at all, but I’d like to ask the people of Japan if they hate me now,” Nomo finished, his eyes looking heavy and downcast. The English interpreter for the American media stumbled over her translation, carefully phrasing for the media that would report Nomo’s words across the globe. Nomo sighed at the end of that sentence and finished in English: “Yes.” Yes, the opinion of the Japanese people about his employment with the Los Angeles Dodgers did matter to him.3 For the 1996 tour was not just about a baseball competition; it was a litmus test of whether the Japanese fans would support a Japanese national playing for another country.

Whether it was the 1994 major-league baseball strike or the long-standing severance of formal relations between the US-based major leagues and NPB that made it nearly impossible for Japanese nationals to play in the majors, labor conditions colored the 1996 Sun Super Major Series between the NPB All-Stars and major-league all-stars.4 In 1993 NPB introduced free agency to its business for the first time. However, the new right for a player to seek his own contract applied only to seasoned veterans who had been in the league for at least 10 years.5 Despite the new contract leverage for players, the highest-paid player in NPB, Hiromitsu Ochiai, earned only 30 percent as much as the highest-paid major-league player at the time. In 1994 major-league players began what became the longest strike in American sports history. This strike among American players resulted in the cancellation of not only the 1994 World Series, but also of the 1994 exhibition tour between the major leagues and NPB.

When major-league players returned to action in 1995, the salaries for the highest-paid players in each league (Barry Bonds and Cecil Fielder) grew over 25 percent in value from the pre-strike highest-paid players.6 As superstars received massive sums of money, the post-strike labor environment propelled the highest-paid players into even grander contracts that made them the envy of the world. Meanwhile, NPB players earned comparatively little and were ineligible to enter the major-league ecosystem because of a labor dispute that had occurred 30 years earlier over the contract of Masanori Murakami, who was the only Japanese national to play in the majors at the time. In short, a spat over one contract that happened a generation earlier had prevented any Japanese from competing for those lucrative contracts. Yet by the 1980s, the Japanese All-Stars squared off every two years in exhibition games against the MLB All-Stars, almost as if they were equals on the baseball field. Something had to change.

In 1995 Japanese agent Don Nomura enticed Hideo Nomo – a five-year NPB veteran who was another five years away from free agency in NPB – to voluntarily retire from his NPB contract with the Kintetsu Buffaloes and enter the National League as an independent free agent. This loophole terminated the Buffaloes’ control over Nomo’s employment, and the Los Angeles Dodgers signed Nomo to a contract exceeding $2 million per year. While Nomo had been a star pitcher for four of his NPB years, after his move to the Dodgers he made nearly as much per year as NPB free-agent pioneer Hiromitsu Ochiai, a 16-time all-star who had been a player for nearly 20 years and held several league records. Nomo had discovered the path to riches, but in the process, he wondered if he had forsaken his countrymen.

Nomo’s controversial move to the majors helps contextualize why he seemed less than thrilled taking the mound against his countrymen in the 1996 Sun Super Major Series. Whether stated overtly or subtly, there was the question of Nomo’s loyalty to Japan. Most of the MLB All-Star roster playing in the series hailed from the United States or its territory Puerto Rico; three Dominican players and one Venezuelan also graced the roster. Nomo stood out as the only player on the MLB All-Star roster who hailed from outside the Western hemisphere. Meanwhile, due to NPB’s strict geographical and racial limits for its players, Japanese nationals made up the entire NPB All-Star roster.7 Therefore, when Nomo pitched, he was the only person in the entire series pitching against one of his countrymen.

“I’d like to ask Japanese people if they hate me now,” Nomo had solemnly said to that room of reporters after his appearance in Game 2 of the series.8 The answer from the Japanese public was a resounding, “No, we still love you.”

The setting for Nomo’s performance was at a tenuous time for Japan. With the Cold War over, Japan was no longer needed as the bulwark of American capitalism in Asia. In 1994 Tomiichi Murayama became the first non-conservative prime minister of Japan since 1947, ending a half-century of conservative leadership. In contrast to the vigilant nationalism that propelled the Japanese economy to become the second most powerful in the world in the 1970s and 1980s, Prime Minister Murayama began a reconciliation tour with Japan’s geographical neighbors. Meanwhile, prominent conservative politician Ishihara Shintaro published a nationalist missive, The Japan That Can Say No, which began with a long lamentation over the weakness of the Japanese athlete that spoke to the greater weakness of the Japanese nation. Ishihara – who would later become a longtime governor of Tokyo and lead the charge to secure the 2020 Tokyo Olympics – wrote in 1991:

[I] sometimes wonder if Japan is not becoming a nation of ETs, that charming visitor from outer space with an oversized head and spindly arms and legs. If that is the course of evolution, ET-like human beings will first appear in Japan. That would explain why we did so poorly at the [1988] Seoul Olympics, winning only a handful of gold medals. Maybe that miserable performance indicates that we are acquiring an unconventional, sophisticated temperament and life-style. As a nation, however, we would be better off if our Olympic athletes won a basket of medals and the younger generation did strenuous work.9

Ishihara’s lament that Japan’s reliance on the technology sector – from the Sony Walkman to Nintendo and Sega video games, from animated movies to small and efficient Toyota cars – had left its people so physically enfeebled that they resembled that helpless alien in the movie E.T., who had flown light years across space only to be made captive by some neighborhood youths equipped with flashlights, dirt bikes, and candy pieces.

In the minds of politicians like Ishihara, international athletic events like the Sun Super Major Series stood as evidence of the persisting physical weakness among the Japanese people. Japan had lost three out of the previous four competitions. And now Hideo Nomo toed the rubber in the Tokyo Dome donning not a Kintetsu Buffaloes uniform but Dodger Blue. The American team was sponsored by – and indeed the Series itself bore the name of – the American technology firm Sun Microsystems. In 1995 Sun Microsystems released the Java programming language that paved the way for the modern internet and computational infrastructure that we all currently live in. In short, the American team represented not only physical superiority, but it also wore the vanguard of the future of technology on its caps. It was not the Sony Series, or the Nintendo Series, or the Toyota Series. It was the Sun Super Major Series. At the center of the endeavor, Nomo and his signature tornado-style windup earned wins for the American team. Fans clamored to the ballparks to see not the Japanese team, but to see the Japanese man who had left Japan. The question on Nomo’s mind was whether they came to cheer, or to jeer. As the series proceeded, the answer clearly pointed to cheering.

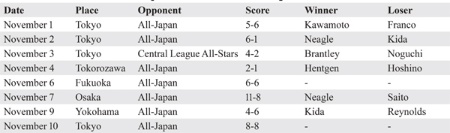

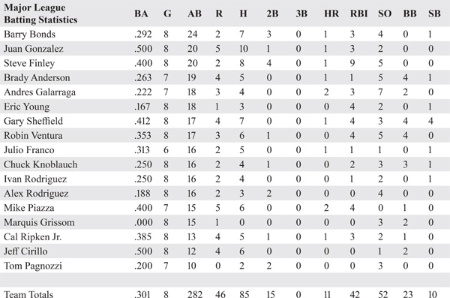

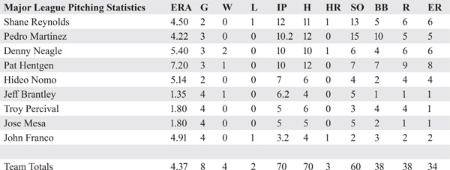

The Sun Super Major Series began on November 1, 1996, in the Tokyo Dome. Although the MLB All-Stars featured an array of legendary hitters who probably need no introduction – Barry Bonds, Alex Rodriguez, Cal Ripken Jr., Gary Sheffield, Mike Piazza – the pitching lineup was rather peculiar. In the era of John Smoltz, Greg Maddux, and Roger Clemens (none of whom were on the tour) – and in a series that had such a rich narrative of intrigue with Nomo’s return to Japan, the leadoff pitcher for the US team was the remarkably unexciting AL Cy Young Award winner Pat Hentgen. Hentgen had finished third in the majors in wins in 1996 and led the league in innings pitched (265⅔), which was likely due to his low strikeout rate of six batters per nine innings.10 Hentgen started three of the seven games and his pitch-to-contact style meant he would rack up the most innings of any MLB starter.

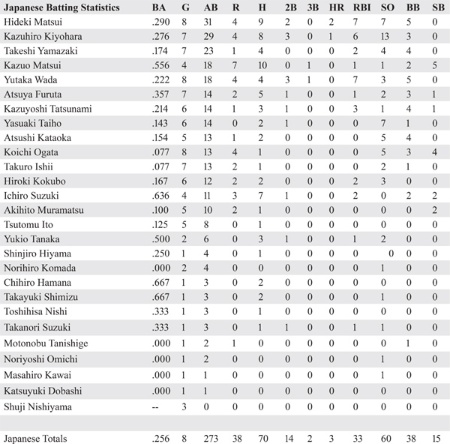

Hentgen struggled out of the gate against the Japanese All-Stars in the first game, allowing a leadoff hit to 23-year-old Ichiro Suzuki, who had just finished his third year as a full-time starter for the Orix Blue Wave. With 116 stolen bases already to his name, Ichiro showed off his speed by stealing second. Hentgen then allowed a walk before facing Hideki Matsui, who had hit 91 home runs in his four years with the Yomiuri Giants. Matsui hit a weak groundball to third base. Robin Ventura fielded the ball but fell, filling the bases on his error. The next batter, Kazuhiro Kiyohara, smashed a weak curveball down the left-field line, emptying the bases with a double. By the time Hentgen got out of the first inning – on a sliding catch in the outfield by Brady Anderson – he had given up five runs.11 The MLB All-Stars caught up by the fifth inning on some sloppy fielding errors by the NPB team. Then side-armer Tetsuro Kawajiri gave up a home run to deep center field that tied the game, 5-5. The Mets’ John Franco entered in relief of Pedro Martinez (who wore the uniform of the now-defunct Montreal Expos) and allowed Ichiro Suzuki to score, which gave the Japanese All-Stars a 6-5 victory in front of 43,000 fans in the Tokyo Dome.

The game the next night was the one Japan had been waiting for. A crowd of 55,000 packed their way into the Tokyo Dome to cheer Hideo Nomo as he played in his first game on Japanese soil since retiring from his NPB contract. The first at-bat of the game was nothing more than a legendary matchup: Hideo Nomo vs. Ichiro Suzuki. So many fans took photos of Nomo – with their flashes popping away as if they were paparazzi on the red carpet – that the public-address announcer had to ask people to put their cameras away.12 Nomo pitched from his famous tornado windup, and Ichiro slapped a pitch right up the middle, right through Nomo’s legs, for a single. Nomo calmed down afterward, finishing three innings of scoreless pitching with three strikeouts.

The crowd cheered Nomo after each out. Nomo responded with a tight and brief grip of his hat brim to signal his appreciation.

The TV cameras closed in on Nomo’s face after each inning, capturing his stoic façade as he walked to the dugout. Nomo completed his outing dispassionately. After he got Ichiro out in his second at-bat, Ichiro stared back at Nomo. He wanted a reaction from Nomo, but the pitcher remained stoic until he arrived back in the MLB dugout, where he placed a windbreaker on his pitching arm and shared some laughs with his teammates. The MLB All-Stars claimed the game, 6-1. Even though Nomo was the centerpiece of the tour, he started the second game of the series instead of the first because he would then be in line to start the sixth game, which would take place in Nishinomiya, a city neighboring Nomo’s hometown of Osaka before a crowd in the legendary Koshien Stadium.

After the second game, the next few games of the tournament branched out to highlight the diversity of Japanese baseball. In the third game the US team’s opposition was the NPB’s Central League All-Stars, featuring players from the Yomiuri Giants and other Tokyo-based NPB teams. The MLB All-Stars won, 4-2. There were three solo home runs, by Cal Ripken Jr. and Steve Finley for the US team and Matsui for the Japanese. Shigeki Noguchi took the loss for NPB while Jeff Brantley claimed the win for MLB.

The fourth game was played at the home stadium of the Seibu Lions, just outside Tokyo on the Seibu Railway Lines. In front of a much smaller crowd, 33,000, the MLB All-Stars claimed a 2-1 victory over the full NPB All-Star team that would finish out the rest of the series. As Pat Hentgen was wont to do, he pitched most of the game efficiently, allowing only one NPB run before giving way to José Mesa for the save.

For the fifth game, the teams moved to Fukuoka, on the island of Kyushu on the far western end of Japan. The MLB All-Stars jumped out to a 4-1 lead thanks in part to a solo home run by Barry Bonds. But Pedro Martinez couldn’t hold a lead. The 25-year-old Martinez – who went on to be considered by many to be the greatest pitcher of his generation if not arguably all-time – loaded the bases in the fifth inning. Jeff Brantley came in relief and allowed a bases-clearing triple to NPB All-Star Kazuyoshi Tatsunami. Martinez allowed five runs in 4⅔ innings. Steve Finley saved Martinez from the loss column with a two-run single in the sixth. As MLB carried a lead into the eighth inning, reliever Troy Percival fielded a bunt poorly and overthrew first base, allowing Yutaka Wada to score and tie the game. This game ended in a 6-6 tie because the teams did not play extra innings during the series. MLB All-Stars manager Dusty Baker remarked that it was the first tie he had been a part of in his major-league career.13

For the finale, the MLB team took its 3-1-1 lead into Koshien Stadium in Nishinomiya, a city near the metropolises of Kobe and Osaka and about 300 miles southwest of Tokyo. There is perhaps no more revered sports ground in Japan than Koshien, the home of the annual high-school baseball tournament. The tournament was once the biggest sporting event in the world. Since the 1920s, organizers invited thousands of boys from across the Japanese Empire to compete on its dirt-only infield for the honor of being called the best baseball team in Asia.14 Although the annual high-school baseball tournament still is a significant cultural event for Japan, there is no longer the sense of militaristic nationalism that once colored it. Koshien now stands as the oldest active stadium – of any sport – in Japan, and it was a homecoming for Nomo to pitch on its field.15

Koshien Stadium had been a common stopping point for so many other international tours, and it’s important to emphasize that it is a field designed for pre-modern high-school players. The infield is entirely dirt, and it always has been that way. There is no grass or turf to slow down or impede a groundball. The pitcher’s mound is lower than a regulation mound. Players warm up nearly within arm’s reach of the bleachers. Homemade videotape footage of Nomo’s performance in 1996 at Koshien exists, and the camera operator was right next to Nomo’s warm-up spot.16 We can clearly see Nomo on the paltry Koshien mound, and it seems that nerves troubled him this time. Nomo gave up four runs on four hits over four innings, but the MLB All-Stars rallied to win, 11-8. By the end of the game, 26 hits had littered the high-school baseball field, with Andrés Galarraga and Gary Sheffield crushing home runs.

In a postgame interview, Nomo said that he wasn’t worried about his poor performance; he merely wanted to perform before his home crowd to give them “a taste of Major League Baseball.”17 Of course, the crowd had seen major-league baseball before, even at this field, where Nomo had been part of the 1992 Japanese team that played the touring MLB All-Stars. But this time, Nomo was part of the major leagues, and likely what he wanted to show his home crowd was the possibility that Japanese people could join major-league baseball – the league that had prevented their entry for so long.

The series finished out quietly on the Japanese east coast with games in Yokohama and Tokyo. In Yokohama, a small crowd of 27,000 was rewarded with a 6-4 NPB All-Stars win. Hideki Matsui crushed a grand slam off MLB starter Shane Reynolds in the second inning, putting the NPB team up 6-0. Reynolds calmed down, however, and he was needed to eat up innings after MLB had used seven pitchers in the previous two games. Reynolds went the distance and nearly claimed a win when his teammates scored four runs in the seventh inning before NPB relievers shut down the MLB offense and saved the second win for the Japanese.

The final game, at the Tokyo Dome on November 11, drew another full house of fans. A total of 13 pitchers took to the mound as offenses unloaded for an 8-8 tie. Mike Piazza, who was popular with the Japanese fans because he was Nomo’s catcher on the Dodgers, thrilled the crowd with the only home run of the game. The MLB All-Stars won the series, four victories to two, with two ties, and Steve Finley of the San Diego Padres (8-for-20, 9 RBIs) was named the Most Valuable Player.18

The 1996 tour hinted at the future of Japanese players in US major-league baseball. Even as Hideo Nomo pitched for the MLB All-Stars, another Japanese pitcher, Hideki Irabu, was negotiating to enter the majors. Irabu’s entry into the American League in 1997 resulted in the creation of the posting system, which would later bring players like Ichiro Suzuki and Hideki Matsui to the United States. Both had faced off against Nomo in the 1996 Sun Super Major Series. As Nomo kept telling the media, he wanted to show off his performance as a major leaguer. Nomo showed the way for others to join the major leagues and sign increasingly lucrative contracts and play in a different – and often more global – competitive atmosphere than existed in Japan. In short, Nomo’s role on the tour was not only to demonstrate that Japanese nationals could effectively play baseball at the major-league level, but to demonstrate that their fellow Japanese fans would support this new era of Japanese players appearing abroad.

The 1996 Sun Super Major Series was won not just by the MLB All-Stars, but by Hideo Nomo. He wondered out loud if Japanese fans and players liked him anymore. And Japanese fans and players answered almost in unison: Hai. Yes, the Japanese were thrilled that Nomo had basically integrated major-league baseball for Japanese players. Nomo’s success in the United States and his pathbreaking move to leave Japan – even at a time when the nation and state felt most vulnerable – opened new avenues of business and culture creation that benefited later players like Ichiro and Matsui. Although the 1996 Sun Super Major Series lasted a little over a week, the implications of the event could be seen for years to come.

BLAIR WILLIAMS (Ph.D., University of Minnesota) is the author of Making Japan’s National Game: A Cultural History of Baseball in Japan (2020). He now works as a technical writer for a global medical device company. He still writes about baseball for Razzball and Pitcher List, and was a finalist for the Fantasy Sports Writers Association Best Baseball Article in 2021.

(Click images to enlarge)

Notes

1 The Series was sponsored by American company Sun Microsystems, thus the “Sun” branding. Throughout this article, I will refer to Japanese players in the anglicized style of given name first, family name second.

2 Because there was no entity named Major League Baseball until a few years later, we will refer to what is now known as Major League Baseball or MLB by using lower-case letters. See also Note 4.

3 “All Japan vs. MLB 1996,” Youtube.com, June 24, 2018. Video of the interview with Hideo Nomo, along with game footage, is available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RrcUNszayIc. For this essay, I maintained the language of Nomo’s English translator who was providing a translation for reporters that omitted some phrases that Nomo used to indicate uncertainty or nervousness. Nomo added some inflections in his Japanese speech that were not fully translated into English by the translator. I incorporated Nomo’s inflections to assist in my narration of his emotional state at the time of the interview.

4 The official program for the 1996 Sun Super Major Series lists the American team as the MLB All Stars.

5 Keiji Kawai and Matt Nichol, “Labor in Nippon Professional Baseball and the Future of Player Transfers to Major League Baseball,” Marquette Sports Law Review 25, no. 2 (2015): 497.

6 Salaries provided at “Yearly League Leaders and Records for Salary,” https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/Salary_leagues.shtml.

7 For more on this, see Blair Williams, Making Japan’s National Game: A Cultural History of Baseball in Japan (Durham, North Carolina: Carolina Academic Press, 2020), Chapter 10: “The Severance of Baseball Communities.”

8 “All Japan vs. MLB 1996.”

9 Ishihara Shintarō, The Japan That Can Say No, trans. Frank Baldwin (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 18-19.

10 Statistics derived from www.fangraphs.com. Pitchers like Roger Clemens and John Smoltz struck out 30 percent more batters than Hentgen. Pitchers who strike out many batters often throw more pitches and thus often appear in fewer innings because they are doing more work per inning than a pitcher who doesn’t strike out many batters.

11 Video highlights of the game with commentary are posted on YouTube: https://youtu.be/LIPQN7IkyjU. Player information taken from www.baseballreference.com.

12 Ken Marantz, “Nomo Lights Up Tokyo with Flashy Effort,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, November 6-12, 1996, 9.

13 “U.S. Plays to a Rare Tie,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 8, 1996: 32.

14 For more information, see Williams, Making Japan’s National Game, Chapter 4: “The Kōshien Tournament.”

15 Koshien Stadium is also the home field of the Hanshin Tigers of NPB’s Central League.

16 Footage available at https://youtu.be/p7LZ608vfag.

17 “MLB Hitters Get Nomo Off Hook,” MLB At Bat, November 7, 1996.

18 “Finley Stars in Japan,” Baseball America, December 9-22, 1996.

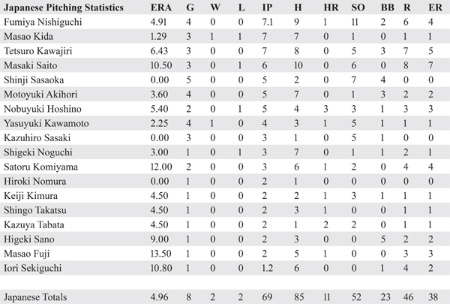

19 These tables include all participants in the series. Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs, U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 109; Nippon Professional Baseball Records, https://www.2689web.com/nb.html.