‘There’s No Joy in Tokyo’: The 1990 Super Major Series

This article was written by Rob Fitts

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1960-2019

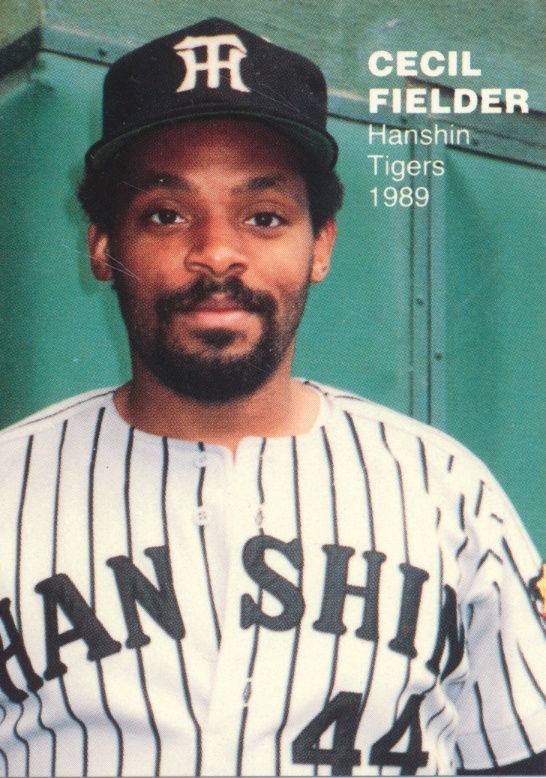

Cecil Fielder on the Hanshin Tigers (Robert Fitts Collection)

In the mid- to late 1980s, tensions between the United States and Japan rose to a level not seen since World War II.1 Americans were frightened at the rising strength of the Japanese economy.

Japanese imports, especially automobiles and electronics, seemed to be taking over the American market. At the same time, Japanese investors began purchasing American real estate, companies, and institutions such as the Pebble Beach golf club and CBS Records. Both politicians and the public feared that Japan would soon surpass the United States economically, marking the end of “the American century.” Japan-bashing – verbal attacks on Japan and physical attacks on Japanese goods – became widespread and talk of “economic war” was endemic.

As the Japanese economy rose, so did the nation’s prowess at baseball. The Nippon Professional League had been gradually improving since World War II. Touring major-league squads, which had beaten their hosts so handily in the 1950s, now faced stiffer competition. The 1974 Mets (9-7-2), 1981 Royals (9-7-1), and 1984 Orioles (8-5-1) had all struggled in Japan. In 1986 the first Nichibei All-Star Series was held, won by the major leaguers six games to one, but in 1988 the Americans escaped with a 3-2-2 record. The time was ripe for the Japanese to defeat America at its national pastime.

On October 31, 1990, a 26-man US all-star team arrived in Tokyo for the eight-game Super Major Series. Leading the Americans was Chicago Cubs manager Don Zimmer, who had played for the Toei Flyers of the Pacific League in 1966. Zimmer did not do particularly well in Japan, on or off the field. He hit just .182 in 203 at-bats and had trouble adapting to the culture. “I don’t eat all that raw fish. I couldn’t stand the smell. I lived on a diet of Campbell’s tomato soup and flounder.”2 Arriving in Japan for the second time, he told reporters, “It’s a great honor for me to be named manager of the all-star team of the major leagues. At the same time, my heart is filled with expectations. We formed the strongest team ever and will play a showdown with a Japan all-star team. I hope Japanese fans will enjoy each of the games.”3

Observers noted right away that the visitors were hardly “the strongest team ever.” Dave Wiggins of the Japan Times wrote, “Sorry to say, but that upcoming all-star baseball series here pitting the Major Leagues against the Japan League will not be a ‘very best vs. very best’ type match-up. The host Japanese contingent does consist of the best available talent at each position. However, some of the major leaguers on hand, though they are solid players, are not the best in the majors at their spots. … The Hallmark Greeting-Card Company has a famous advertising slogan: ‘If you care to send the very best, send Hallmark.’ Somehow I don’t think Hallmark and Major League Baseball do much business together.”4

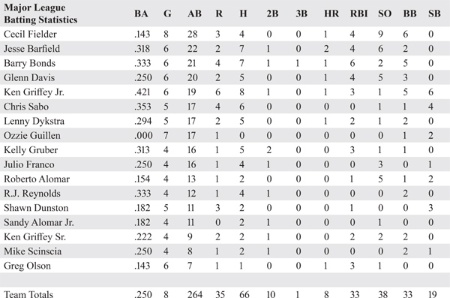

Headlining the American roster were National League MVP Barry Bonds, Oakland A’s ace Dave Stewart, Cincinnati Reds “Nasty Boy” Rob Dibble, and father and son teammates Ken Griffey and Ken Griffey Jr. Also on the roster were two up-and-coming young players who were eventually enshrined at Cooperstown: Randy Johnson and Robert Alomar.

The real star, however, was American League home run and RBI champ Cecil Fielder. After signing professionally in 1982, Fielder spent eight years trying to break into a major-league lineup with little success. In late 1988 the Toronto Blue Jays sold his contract to the Hanshin Tigers of the Central League. Fielder blossomed in Japan, batting .302 with 38 home runs and a 1.031 OPS. With his mammoth production and physical size, he became a favorite among the rabid Hanshin fans. His success in Japan allowed Fielder to sign with the Detroit Tigers as a free agent after the 1989 season. Probably no one expected Fielder to surpass his NPB numbers in the majors, but he nearly did – leading the American League with 51 home runs and 133 RBIs along with a .277 batting average and a .969 OPS. For most Japanese fans it was a validation of the strength of Nippon Professional Baseball, showing that the leagues were not that far apart.

“In most cases, foreign players have been at the end of their careers when they come here,” explained Peter Miller, a consultant to the Major League Baseball Players Association who lived in Tokyo at the time. “But Cecil, he learned patience at the plate and how to hit home runs here. Then he went back. Now, he’s considered a hometown boy.”5 Everywhere Fielder went he was mobbed by Japanese media and fans. “Fielder’s every move provoked a commotion. Dozens of photographers, standing at ease most of the time, would spring into action with each Cecil sighting.”6

Opposing Fielder and his major-league teammates was a strong Japanese squad. Built around a rotating roster, the squad contained nearly every star in the league. The Japan All-Stars consisted of a core 20-man roster that included future Hall of Famers Hideo Nomo, Koji Akiyama, and Hiromitsu Ochiai. This core roster was supplemented by six additional players for each of the eight games. The team’s manager and coaching staff also rotated. Motoshi Fujita managed the first two games, Masaaki Mori the third, Koichi Tabuchi the fourth, Katsuhiro Nakamura the fifth, Masaichi Kaneda the sixth, and Sadao Kondo the final two. In all, 62 of the eligible 64 men played on the Japanese squad.

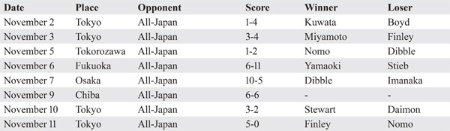

The series opened at Tokyo Dome on Friday evening, November 2. Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd started for the major leaguers against a 22-year-old rookie named Hideo Nomo. Known as “The Tornado” due to his corkscrew windup, Nomo was not drafted after high school by any professional team. Instead, he honed his skills in Japan’s industrial leagues in 1988 and pitched for Japan’s Olympic team. The Kintetsu Buffaloes drafted Nomo in 1989 and he made his professional debut the following season. He was an instant success, leading the Pacific League with 18 wins, 287 strikeouts, 235 innings pitched, and a 2.91 ERA. He won the league’s MVP and Rookie of the Year Awards.

Nomo’s debut against major-league hitters, however, did not start well. He began by walking leadoff hitter Ken Griffey Jr. and then plunked his father. Following Japanese baseball etiquette, the young pitcher removed his cap and bowed to Griffey Sr. to show that the errant pitch was unintentional. The son then stole third base as Nomo retired Julio Franco, putting runners at the corners with one out and Cecil Fielder coming to the plate. Perhaps overawed by Fielder’s reputation, Nomo walked the Tiger intentionally and would now have to face Barry Bonds with the bases loaded. Bonds responded with a sharp single to center, scoring Griffey Jr. It looked as though it would be a long night for the Japanese team and its fans, but then the American bats went silent. Nomo pitched out of the inning by retiring Kelly Gruber and Jesse Barfield. Nomo and relievers Hiromi Makihara, Yukihiro Nishizaki, Masumi Kuwata, and Masao Kida surrendered just one more hit (an infield single by Sandy Alomar Jr. in the seventh) and no runs over the next eight innings. Zimmer noted that the Japanese kept the major leaguers off balance by pitching “backwards.” “Every time [they] got behind a hitter, they never threw a fastball. They’d throw curves, fork balls and we didn’t hit them.”7

Overall, Boyd and relievers Randy Johnson and Rob Dibble pitched well, allowing only four hits and striking out 12, but the Japanese bundled their hits. In the third inning, Takahiro Ikeyama doubled off the left-center-field wall with runners on first and third to put his team on top, 2-1. Tatsunori Hara then singled in Ikeyama to increase the lead to 3-1. The NPB All-Stars scored again in the seventh to seal the victory as Kaoru Okazaki scored on Akinobu Okada’s sacrifice fly.

One of the game’s highlights came from Dibble. “The fans were … in awe of the speed of the Nasty Boy’s pitches as the radar readings were flashed across the scoreboard. The murmurs grew louder and louder as pitch after pitch exceeded 150 kilometers per hour (93 mph). Yomiuri shortstop Masahiro Kawai, aware of Dibble’s ability to heave the horsehide more than 100 mph, drew laughter and applause for doffing his cap after he grounded out to second. He was ecstatic, he had hit the ball.”8

The loss did not seem to concern Zimmer or his players. Since 1951 visiting major-league squads had lost nine of the 19 opening games. The Americans usually arrived jet-lagged and out of practice. “For most of the guys, it’s been a month since they faced live pitching,” noted Fielder. “It’s going to take a couple of days to get our timing back. Once we get our mechanics back, we’re going to show a good brand of baseball.”9

The visitors’ slump continued the following day as a sellout crowd of 56,000 packed Tokyo Dome for the second game. In the second inning, Koji Akiyama doubled off starter Chuck Finley and scored on an attempted steal of third as catcher Mike Scioscia’s throw went into left field. In the bottom half of the inning, the Americans grabbed the lead as Fielder singled and scored on Glenn Davis’s two-run homer. But then the Japanese pitchers took over and retired 20 of the next 21 batters. Meanwhile, the NPB All-Stars retook the lead in the third inning on a two-run single by Kazuhiko Ishimine and added an insurance run in the top of the ninth to lead 4-2.

Chunichi Dragons rookie closer Tsuyoshi Yoda, “usually noted for his pinpoint control,” began the bottom of the ninth by walking Chris Sabo and Barry Bonds.10 The excited fans rose to their feet as Cecil Fielder strode to the plate with the tying runs on base. But those expecting the fairy-tale ending were disappointed as Fielder grounded into a 6-4-3 double play. With two outs and Sabo on third, Davis picked up his third RBI of the evening with a single, but Ozzie Guillen flied out to end the game and give the Major League stars their second straight defeat. To quell the major-league bats, manager Motoshi Fujita had used five pitchers: starter Masaki Saito (three hits in two innings), Kazutomo Miyamoto (no hits, one walk in three innings), Tomio Watanabe (perfect for two innings), Hiroaki Nakayama (one perfect inning), and Yoda. Zimmer noted that it was difficult for his batters because “the Japanese ‘might only use a pitcher for two innings and then he’s gone and then you have to start over again’ learning the next pitcher.”11

After a rainout on Sunday, November 4, the series continued the following day at Seibu Stadium in Tokorozawa, a suburb of Tokyo. Lions manager Masaaki Mori took over the helm for the Japanese squad. Before the game, Mori warned the media and fans not to underestimate the visitors after the two losses, noting that the players had been away from the game for a month. “It is wrong to consider that the major leaguers’ strength has diminished,” he concluded.12

Dave Stewart, the intimidating ace of the Oakland Athletics, took the mound for the Americans against Hisanobu Watanabe of the Seibu Lions. The major leaguers struck early as Ken Griffey Jr. doubled and scored on a single by Barry Bonds with one out in the first. Stewart battled the NPB All-Stars, holding them scoreless until the fifth, when they pushed the tying run across on doubles by Tsutomu Ito and Hatsuhiko Tsuji.13

The major leaguers had plenty of chances to score as they racked up 11 hits, worked out three walks, and had two hit batsmen off a succession of six pitchers. In the sixth, they left the bases loaded as Glenn Davis struck out looking to end the inning. Julio Franco and R.J. Reynolds began the seventh with back-to-back singles, but Franco was out trying to advance to third on Ozzie Guillen’s fly out to center field and Greg Olson struck out to retire the side. In the top of the eighth the Americans threatened again, placing runners at the corners with two outs but Hideo Nomo, on in relief, induced Davis to ground back to the mound for the third out.14

The Japanese broke the tie in the bottom of the eighth as Kenichi Yamazaki singled off Rob Dibble. Mori brought in speedster Norifumi Nishimura to pinch-run and he stole second before scoring on Makoto Sasaki’s single.15

Once again Yoda came on to close the game, and once again the rookie nearly fell apart. After allowing hits to Franco and Reynolds, Yoda retired Guillen but walked pinch-hitter Mike Scioscia to load the bases. Bearing down, the closer retired Chris Sabo on a shallow fly ball and Griffey Jr. on a groundout to end the game. “I’m trying everything to win,” proclaimed Zimmer. “We want to win. We all want to win. But they’ve outplayed us. They’ve won three in a row. All we can do is to come out tomorrow and try to win.”16

Only 23,000 came to watch the fourth game, at Heiwadai Stadium in Fukuoka. To top the skid, Zimmer turned to Blue Jays ace Dave Steib, who had just finished a strong season with 18 wins, a 2.93 ERA and a no-hitter against Cleveland on September 2. The game remained close for three innings as the Japanese scored one in the first and the Americans tied it on Jesse Barfield’s home run in the second. But in the top of the fourth, the roof collapsed on Steib and his teammates as the Japanese took a 3-1 lead on a two-run single by Koji Akiyama. They added three more runs the next inning, another three in the sixth, highlighted by Hiroo Ishii’s two-run homer, and capped it off with a two-run seventh. In all, the NPB All-Stars scored 11 times on 20 hits, four walks, and four American errors. Makoto Sasaki led the onslaught by going 5-for-6 while Ishii went 3-for-3 in the 11-6 victory.17

With the fourth consecutive Japanese victory, the media on both sides of the Pacific began paying more attention to the series. Newspapers across the United States ran an Associated Press article that began, “First it was cameras, cars and electronics. And now, horror of horrors, is baseball to be the next U.S. industry to find itself outgunned by the Japanese juggernaut? The question, which would have evoked laughs last week, seems suddenly pertinent after the showing of a major league all-star team touring Japan for an eight-game series.”18

Some in the Japanese media began to crow. One Nippon Television national newscaster proclaimed that “the major leaguers have received a lesson since coming to Japan.”19 Another NTV announcer during the nightly sports highlights on November 6 pontificated “about the strong Japanese yen and the weak American dollar and strong Japan league pro baseball players and weak American major leaguers. And then for good measure, he add[ed] the Americans have lost face.”20

According to Washington Post foreign correspondent T.R. Reid,

Sportscasters here have put together a hilarious bloopers tape made up of bonehead plays made by the visiting Americans. As the tape unfolds, we see Cleveland catcher Sandy Alomar Jr., the American League’s rookie of the year, drilling a pick-off throw so far into right field that the runner he is trying to nail manages to score from first. Montreal pitcher Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd is seen talking to himself after walking in a run; three U.S. fielders bump into one another while a pop fly drops in short right; and American manager Don Zimmer of the Chicago Cubs looks sorrier and sorrier in the forlorn U.S. dugout.21

Other Japanese, however, were angry with their team’s success. “We would rather see the Americans play very well and have the Japanese lose,” said Takeyuki Hayashi, a baseball writer for Nikkan Gendai. “We want to see what we cannot watch from our own players. We want to see power and speed. … It’s not a matter of winning or losing. We just want to watch good baseball.”22

Many concluded that the major leaguers were not taking the games seriously. A columnist for Shukan Gendai “contended that the U.S. players have been spending too much time at soapland,” the Japanese term for erotic wet massage parlors usually run by prostitutes.23 Most critics, however, believed that the visitors just lacked focus and the desire to win. Mikio Takeda, of the tour’s sponsor Mainichi Newspapers, noted that the “Japanese [are] very disappointed. I really felt like the Japanese players can never beat these guys. But look at the result. After the Americans lost the first game, maybe they’re sleepy. Then second loss, third, fourth. I figured maybe [the] Americans [are] weak.”24 Kazuhiro Kiyohara, the Japanese first baseman, added, “I really know Americans play better; I’ve gone over there. … I know Japanese can’t play with the Americans. But the American players maybe lost their concentration.”25 When asked if he felt the major leaguers were trying, Hideo Nomo said, “I don’t know. I’m sure I want to win, but I don’t know about them.”26

The defeats led to a rift in the major-league squad. “This is supposed to be our all-star team,” said coach Don Baylor. “We haven’t executed. We’ve played poor baseball. Some guys are here on vacation and maybe some guys came here to take the money and go home.”27 Ken Griffey Sr. noted the lack of intensity among some of the younger players: “There’s a difference and I think it started with the guys who came up after 1985. They want to win. [But] Sometimes you wonder if they know how all the time.” Griffey Sr. felt the need to have some discussions on attitude with his son. One “centered on young Griffey’s casual stroll off the field after making an out.”28

Twenty-six-year-old Rob Dibble said, “Our guys are just doing this for fun and a little more baseball. There’s not a lot riding on these games and nobody’s going to go out and get hurt, either. The pitchers aren’t throwing 100 percent and just throwing strikes and getting them out as best you can. But when you come down to it, your livelihood is in the States. That’s what it’s all about.”29

But veterans like Dave Stewart disagreed, “We came over here to win; this isn’t a joke. Maybe we should refocus on what we should be doing. They’re trying to beat us. Why shouldn’t we be trying to beat them? … I didn’t come 8,000 miles to lose. Losing ruins your whole day.”30

On November 7 fans came out to Koshien Stadium, home of the Hanshin Tigers, to welcome Cecil Fielder back to Osaka. Journalist Harry F. Thompson observed, “While all 58,000 seats are not sold out for Wednesday’s game (strange, considering how the Japanese have taken to public gloating in recent days over their surprising lead in the fall exhibition tour), crowds have formed outside ticket windows since sunrise in hopes of buying a cheap ($23) bleacher seat.”31

Randy Johnson took the mound for the Americans. The 6-foot-10 left-hander had just finished his second full season in the big leagues and showed promise with a 14-11 record and a 3.65 ERA, and was named to the American League All-Star team. His league-leading 120 walks, however, were worrisome. At the time, few would have predicted that he would mature into a Hall of Fame pitcher. The Japanese All-Stars pounced on Johnson as Hiromitsu Ochiai hit a two-run homer in the first and Katsumi Hirosawa hit a two-run home run in the fourth. The Japanese scored another in the fifth on a botched pickoff to enter the eighth inning with a 5-2 lead.32

Chris Sabo began the inning with a single to left off southpaw Shinji Imanaka and an out later Barry Bonds followed with a single to center. Then hometown hero Cecil Fielder came to the plate. Fielder had had a disappointing series, going 2-for-17 without an extra-base hit. But on his special day, the big slugger came through, blasting a curveball deep into the left-field bleachers to tie the game, 5-5. “They were laughing at us after the fourth loss,” said Fielder. “They were having a great old time in the other dugout. But they sure got quiet in a hurry, didn’t they? This one felt real good.”33

Surprisingly, Japanese manager Katsuhiro Nakamura left Imanaka on the mound. He retired Glenn Davis but Julio Franco singled and stole second, bringing up right-handed batter Jesse Barfield with two outs. Rather than bring in a righty to face Barfield, Nakamura stayed with Imanaka. Barfield punished them by smashing a home run to deep left to capture the lead. In the ninth, with a battered Imanaka still pitching, the Americans added to their lead with a two-run homer from Griffey Jr. and a solo home run from Bonds. The night ended with a 10-5 major-league victory. The suffering Imanaka got the loss, having surrendered eight hits and eight runs in two innings. “We were getting tired of losing,” noted Griffey Jr. “We finally won one, and it felt good. Now, maybe, we can go out and win the next three.”34

But it was not to be. On November 9 at Chiba Lotte Marine Stadium, the Japanese All-Stars went out to a 4-0 lead in the second inning and added two more in the fourth against starter Dennis Boyd. Although the Americans got three back, including a run off 21-year-old Hideki Irabu, they entered the seventh inning down 6-3. Reliever Hisao Niura immediately ran into trouble, giving up a hit and two walks to load the bases with one out. Game 6 Japanese manager Masaichi Kaneda brought in Yoshihisa Shiratake but to no avail as Kelly Gruber hit a two-run single and Jesse Barfield followed with a game-tying single past shortstop Takahiro Ikeyama.35

Tsuyoshi Yoda shut down the major leaguers in the bottom of the eighth and the teams entered the ninth knotted, 6-6. Zimmer gave the ball to Bobby Thigpen, the White Sox closer, who had a 1.83 ERA and 57 saves during the 1990 season.

Katsumi Hirosawa led off by slicing a line drive down the right-field line. Barfield sprinted to his left and made a sliding catch to save an extra-base hit, ripping his pants in the process. “Earlier in the game, Barry Bonds and Griffey and I got together and decided to take the line away from those guys,” said Barfield. “The left-handed guys were hooking the ball down the line and the righties were slicing the ball. So I just moved over a couple of steps. I had a good jump on the ball. Had I been straight up, I never would have gotten to the ball. … That’s one of my favorite plays – running to my left and sliding after the ball.”36 Thigpen then walked the next two batters. With the game on the line, he settled down and got consecutive groundouts to end the inning.

Yoda pitched a scoreless bottom of the ninth. As the Americans collected their items off the bench and headed to the locker room, one of their teammates asked,

“Where’s everybody going?”

“It’s over. In Japan, games end in a tie,” he was told.

“A tie? What do you mean a tie game? We don’t play to ties!” the player asked incredulously.37

“I haven’t been in a tie since Little League” … Rob Dibble said with disgust.

“It’s the first time in my life and I don’t like it,” Jesse Barfield added.

At least, “It’s better than losing,” said Don Zimmer, shrugging his shoulders.38

With the tie, the Japanese All-Stars clinched the eight-game series. Not counting the San Francisco Giants’ 3-6 record during their 1970 spring-training games in Japan, it was the first time a professional American team would leave Japan with a losing record.

After playing strong baseball for six games, the Japanese squad seemed to relax after clinching the series. Game 7 at Tokyo Dome was sloppy with the hosts “committing three errors, two wild pitches, a passed ball and a hit batsman.”39 Even with these gaffes, the major leaguers had difficulty scoring off the five pitchers used by the Japanese. The Americans’ first run came in the fourth when Fielder walked and moved to second on a passed ball. Glenn Davis grounded to short and Fielder got hung up between second and third. Shortstop Takahiro Ikeyama “ranged far to his right to make the stop and tried to pick Fielder off second with an off-balance throw. The ball sailed wide of the base and into shallow right field, allowing Fielder to lumber around third and barely beat the throw to the plate.”40 Lenny Dykstra put the Americans up 2-0 the following inning with a home run down the right-field line.

Meanwhile, starter Dave Stewart dominated the NPB All-Stars, throwing six shutout innings, until the seventh. The inning began with a double by Norihiro Komada. After a spectacular diving catch by shortstop Ozzie Guillen, Atsuya Furuta singled home Komada. Koji Akiyama then tripled off the right-field wall to score Furuta and tie the game, 2-2. In the top of the eighth, the numerous Japanese misplays caught up with them. Ken Griffey Jr. led off with a single, advanced to second on a wild pitch by Kazuhiko Daimon, and kept running, just beating the throw as he slid safely into third base. After Dykstra popped out, Daimon uncorked a second wild pitch, allowing Griffey to score. Now up 3-2, Zimmer brought in Dibble, who closed the game with two scoreless innings to seal the 3-2 victory.41

Chuck Finley took the mound at Tokyo Dome on November 11 for the final game of the series. Finley had not pitched well in his first start, losing Game 2. And he looked shaky in this final outing as he walked Hiromitsu Ochiai and Hiroo Ishii in the second but was saved by inducing Mokoto Sasaki to ground into a double play to end the inning. As the game went on, Finley settled down and looked stronger, keeping “the Japanese hitters off balance by changing speeds and working the corners with his forkball.”42 At the end of three innings, he had a no-hit shutout.

The first two Japanese batters reached base in the fourth on consecutive errors by Ozzie Guillen and Kelly Gruber, but Finley retired the heart of the opponents’ order – Ochiai, Katsumi Hirosawa, and Ishii – to keep the shutout and no-hitter alive. As Finley thwarted the Japanese, his teammates put up five runs. Three came in the second inning off Hideo Nomo when Greg Olson “drilled a waist-high fastball deep into the left-field bleachers.”43 “I played in six of the eight games, mostly as a late inning defensive replacement,” said Olson. “It was great to make my only hit such a big one.”44 The Americans picked up two more runs in the third on RBI doubles by Griffey Jr. and Gruber.

At the end of the fifth inning, Zimmer, following a game plan designed to protect his starter’s arm, took Finley out despite the no-hitter. “After throwing 240-plus [sic] innings [during the 1990 season] you don’t know how your arm’s going to react after you shut it down for a month and then crank it back up,” Finley explained. “I could’ve gone one more inning but I wasn’t going to push it.”45 While Finley had been primarily using off-speed pitches, reliever Randy Johnson threw hard. “I don’t think these guys [the Japanese] have seen many fastballs over 90 miles an hour,” Johnson noted.46 The contrast helped baffle his opponents. Johnson cruised through the remaining four innings, striking out four and walking two. “The crowd was into it,” said Johnson.47

“Every time Randy threw a strike in the last inning you could see him grip his glove a little harder,” said the catcher, Olson. “It was the same for me. I didn’t want to make any mistakes in the last inning so I said let’s go with his best pitch, so he went fastball the whole last inning. We didn’t even mess around with anything else.”48

“I started getting pumped up in the last inning and threw a lot of strikes,” said Johnson. “Maybe I had a little more adrenaline today because there was a no-hitter on the line. Maybe it was because the reputation of American baseball was on the line.”49

“It was a good way to close for us,” said Cecil Fielder after the 5-0 win. “I just came to have some fun.”50 But Japan Times writer Greg Hardesty summed it up best: “Any lingering snickers among critics of the Major League’s lackluster performance in the Super Major League Series’ early games were silenced forever when catcher Tsutomu Ito of the Seibu Lions flew out to right fielder Jesse Barfield to end the history-making game.”51

Although the Americans had redeemed themselves in the final games, their losing record received national attention. Critics often related the Japanese success on the diamond with their economic success and the ongoing US-Japan trade issues. “Made in Japan: Better Baseball” read a headline in Newsweek.52 Jim Impoco of U.S. News & World Report wrote, “Future historians attempting to pinpoint the end of the American Century may want to look no further than a short-porched ballyard near the heart of this teaming capital where a major-league-baseball all-star team from the States came, saw – and was conquered. … At a time when U.S. industry is under mounting pressure from hard-charging Japanese competitors, it’s hard to resist comparisons.”53 An exasperated American banker working in Tokyo exclaimed, “We’re not even No. 1 in baseball anymore. … What’s left?”54

Japan Times columnist Dave Wiggins, however, disagreed. “The reality of the situation is that this recent ‘goodwill’ series is, or at least should be, all about baseball – nothing else. Not economics and certainly not a country’s worth.”55 There were, Wiggins argued, several reasons for the Japanese victory.

As pointed out before the games began, the major-league roster consisted of talented players willing to make the postseason trip to Japan – not the best players in the league. Of the 30 top batters in the 1990 major-league season, according to Wins Above Replacement (WAR), only six came to Japan. None of the top 10 pitchers, according to WAR, and just three of the top 30 made the trip. In contrast, the 64-man Japanese roster included nearly every top Japanese player. It was a true all-star squad. Furthermore, most of the Japanese managers took advantage of the large roster to limit their pitchers to just two innings per game. During the eight-game series, the Japanese used 35 different pitchers. As a result, the Americans rarely faced the same pitcher twice, denying them the opportunity to see all of their opponents’ pitches or determine pitching patterns.

The monthlong layoff between the end of the major-league season and the trip to Japan with only one day of recovery and practice after arrival undoubtedly hurt the American players. Bodies became sore and stiff; the hitters had lost their timing and the pitchers lost the feel of the ball. “If you lay off for about a month, you might as well be off for the whole winter. You lose your edge very quickly. It’s taken us a little time, but as the series progressed I think we played a little better baseball,” reflected Mike Scioscia.56 Nearly all the players complained about the layoff and difficulty of playing at full intensity. But other visiting American teams had suffered similar layoffs and still returned home with winning records.

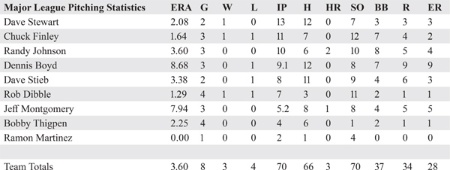

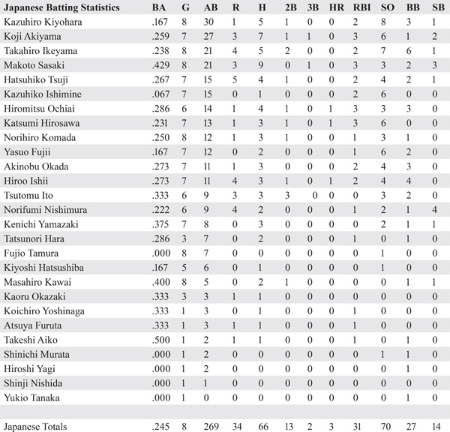

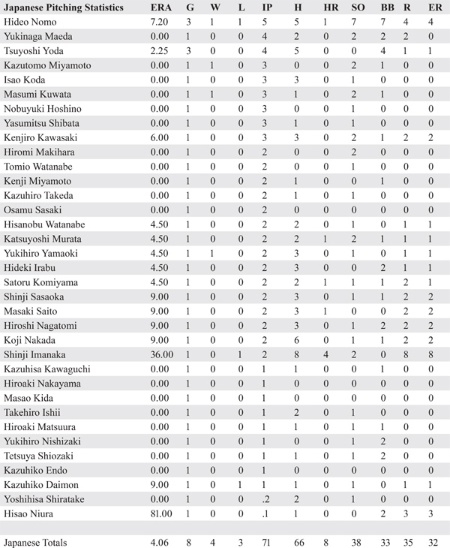

The biggest factor in the American defeat was the strength of the Japanese players. Not only did they play with intensity but the gap between the major leagues and Nippon Pro Baseball was narrowing. “I frankly don’t think there’s much difference anymore,” said Cecil Fielder. “The Japanese have come a long way, and you can’t really say they’re far behind now.”57 In the first all-star series, held in 1986, the Americans comfortably won six of the seven games as the Japanese team ERA was a lofty 6.71. “When I played there in 1986, the pitching wasn’t that good,” recalled Jesse Barfield. “The difference is [now] they’re getting their breaking balls over anytime in the count. They didn’t do that in 1986. They had to rely on fastballs and they weren’t blowing them by us. Now they have some pretty decent cheese to set up that off-speed stuff anytime they want to throw it.”58 Two years later, the Japanese staff held the visitors to 3.98 earned runs per game, as the major-league team escaped with a 3-2-2 record. In 1990 the Japanese ERA was nearly identical, 4.06, but their teammates raised their batting average more than 30 points, from .212 to .245. (The Americans hit .250 during the series.)

“Their hitters are getting bigger and stronger,” explained Zimmer, “and their pitching is terrific. They have good stuff, change speeds well and most of all, have outstanding control.” “Maybe in the past, the U.S. could just show up and win easily, but no more. In the future the Major Leaguers will have to take these games more seriously and prepare better if they hope to win. The Japanese have become that good. We should have learned an important lesson.”59

Commissioner Fay Vincent agreed. “We’ve clearly got to do a better job starting with the process because you don’t want to come over here and be embarrassed. And everyone involved has got to be embarrassed, starting with me and going down to the players.”60 “When this is over,” he added, “we’ll sit down and think about what we can do to improve the caliber of play.”61

And indeed, when the major-league all-stars returned in 1992, they were prepared for revenge.

ROBERT K. FITTS is the author of numerous articles and seven books on Japanese baseball and Japanese baseball cards. Fitts is the founder of SABR’s Asian Baseball Committee and a recipient of the society’s 2013 Seymour Medal for the Best Baseball Book of 2012 (Banzai Babe Ruth); the 2019 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award; the 2012 Doug Pappas Award for the best oral research presentation at the annual convention; and the 2006 and 2021 SABR Research Awards. He has twice been a finalist for the Casey Award and has received two silver medals at the Independent Publisher Book Awards. While living in Tokyo in 1993-94, Fitts began collecting Japanese baseball cards and now runs Robs Japanese Cards LLC. Information on Rob’s work is available at RobFitts.com.

Notes

1 T.R. Reid, “There’s No Joy in Tokyo for U.S. Team,” Washington Post, November 10, 1990: A22.

2 Don Zimmer with Bill Madden, Zim: A Baseball Life (New York: Total Sports, 2001), 73.

3 Associated Press, “Major Leaguers Arrive in Tokyo,” Japan Times, November 1, 1990: 20.

4 Dave Wiggins, “Baseball Series Draws Some, but Not All, of the West’s Best,” Japan Times, November 1, 1990: 21.

5 Claire Smith, “The Return of Cecil: An Event in Japan,” New York Times, November 4, 1990: S6.

6 Smith, “The Return of Cecil: An Event in Japan.”

7 Brent Johnston, “Major Leaguers Bow 4-1 in Opener,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 4, 1990: 36.

8 Johnston, “Major Leaguers Bow 4-1 in Opener,” 35.

9 Johnston, “Major Leaguers Bow 4-1 in Opener,” 36.

10 David Duncan, “Japan All-Stars Nip ML Visitors 4-3,” Japan Times, November 4, 1990: 15.

11 Duncan, “Japan All-Stars Nip ML Visitors 4-3.”

12 Associated Press, “U.S.-Japan Baseball Rained Out,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 6, 1990: 24.

13 Associated Press, “Major Leaguers Lose Third,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 7, 1990: 25.

14 Fujiyoshi Tamura, “ML Squad Finally Getting Hits, but Fall Again to Japanese 2-1,” Japan Times, November 6, 1990: 22.

15 Associated Press, “Major Leaguers Lose Third.”

16 Tamura.

17 Associated Press, “Are Japan, U.S. Baseball Equals?” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 8, 1990: 26, 28; Kyodo News, “Japanese All-Stars Win Again, Stretch Streak to Four Games,” Japan Times, November 7, 1990: 18.

18 Dan Biers, “Japanese Talent Hits Home to Americans,” Odessa [Texas] American, November 7, 1990: 5B.

19 Associated Press, “Are Japan, U.S. Baseball Equals?”

20 Dave Wiggins, “Let’s Keep the Series in Perspective,” Japan Times, November 15, 1990: 23.

21 Reid.

22 Harry F. Thompson, “Japan Tour a Humbling Trip for All-Stars,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 15, 1990: 25.

23 Reid.

24 Claire Smith, “Good-Will Tour Is Producing Some Hard Feelings,” New York Times, November 8, 1990: D25

25 Smith, “Good-Will Tour Is Producing Some Hard Feelings.”

26 Smith, “Good-Will Tour Is Producing Some Hard Feelings.”

27 Claire Smith, “Good-Will Tour Is Producing Some Hard Feelings.”

28 Smith, “Good-Will Tour Is Producing Some Hard Feelings.”

29 Smith, “Good-Will Tour Is Producing Some Hard Feelings.”

30 Smith, “Good-Will Tour Is Producing Some Hard Feelings.”

31 Harry F. Thompson, “Joy at Koshien Stadium – Fielder-san Returns,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 9, 1990: 27.

32 Kyodo News, “Major Leaguers Win Game 5 on HRs by Fielder, Barfield,” Japan Times, November 8, 1990: 20.

33 Tom Pedulla, “Big-Leaguers Finally Win One vs. Japan.” Unattributed news clipping, Tours of Japan Folder, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

34 Harry F. Thompson, “Happy Homecoming for Fielder in Osaka,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 9, 1990: 27.

35 Brent Johnston, “Tie in Japan Puzzles Major Leaguers,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 9, 1990: 35-36; Kumi Kinohara, “U.S. All-Stars Forge 6-6 Tie in Super Series’ Chiba Clash,” Japan Times, November 10, 1990: 16.

36 Johnston, “Tie in Japan Puzzles Major Leaguers.”

37 Johnston, “Tie in Japan Puzzles Major Leaguers.”

38 Johnston, “Tie in Japan Puzzles Major Leaguers.”

39 Harry F. Thompson, “Stewart-Dibble Combo Clicks in Tokyo,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 12, 1990: 28.

40 Thompson, “Stewart-Dibble Combo Clicks in Tokyo.”

41 Dave Duncan, “ML Squad Captures Game 7,” Japan Times, November 11, 1990: 14; Thompson, “Stewart-Dibble Combo Clicks in Tokyo.”

42 Harry F. Thompson, “Major Leaguers Close Out with No-Hitter,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 13, 1990: 26.

43 Thompson, “Major Leaguers Close Out with No-Hitter,” 28.

44 Thompson, “Major Leaguers Close Out with No-Hitter,” 28.

45 Thompson, “Major Leaguers Close Out with No-Hitter,” 26.

46 Thompson, “Major Leaguers Close Out with No-Hitter,” 26.

47 Thompson, “Major Leaguers Close Out with No-Hitter,” 28.

48 Thompson, “Major Leaguers Close Out with No-Hitter,” 26.

49 Thompson, “Major Leaguers Close Out with No-Hitter,” 26, 28.

50 Greg Hardesty, “ML Tosses No-Hitter in Finale,” Japan Times, November 12, 1990: 10.

51 Hardesty, “ML Tosses No-Hitter in Finale.”

52 Bill Powell, “Made in Japan: Better Baseball,” Newsweek, November 19, 1990: 79.

53 Jim Impoco, “Dateline: Sayonara, Sluggers,” U.S. News & World Report, November 19, 1990: 20.

54 Powell.

55 Wiggins, “Let’s Keep the Series in Perspective.”

56 Thompson, “Japan Tour a Humbling Trip for All-Stars.”

57 Reid.

58 Thompson, “Japan Tour a Humbling Trip for All-Stars.”

59 Wiggins, “Let’s Keep the Series in Perspective.”

60 Smith, “Good-Will Tour Is Producing Some Hard Feelings.”

61 Thompson, “Japan Tour a Humbling Trip for All-Stars.”

62 These tables include all participants in the series. Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs, U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 107; Nippon Professional Baseball Records, https://www.2689web.com/nb.html.