Fred Odwell: The Oddest Home Run Champion of them All

This article was written by Mike Lackey

This article was published in SABR Deadball Era newsletter articles

This article was published in the SABR Deadball Era Committee’s August 2021 newsletter.

If Fred Odwell isn’t the most obscure home run champion in the history of major league baseball, it’s only because the competition is surprisingly stiff. After all, who remembers Oyster Burns, who shared the National League lead in 1890, or Braggo Roth, who led the American League in 1915? Who remembers that when Babe Ruth won his first home run crown, leading the AL with 11 in 1918, he shared the honor with Tilly Walker? Even considering comparatively recent time, how many fans remember Nick Etten, who led the AL (with 22) in 1944, when the unavailability of rubber forced the use of inferior balls?1

If Fred Odwell isn’t the most obscure home run champion in the history of major league baseball, it’s only because the competition is surprisingly stiff. After all, who remembers Oyster Burns, who shared the National League lead in 1890, or Braggo Roth, who led the American League in 1915? Who remembers that when Babe Ruth won his first home run crown, leading the AL with 11 in 1918, he shared the honor with Tilly Walker? Even considering comparatively recent time, how many fans remember Nick Etten, who led the AL (with 22) in 1944, when the unavailability of rubber forced the use of inferior balls?1

The fact that Odwell, an outfielder with the Cincinnati Reds, needed only nine homers to lead the National League in 1905 wasn’t unusual at the time. Home runs totaled just 338 in both major leagues during Odwell’s big year and dipped below 270 from 1906 to 1909 before rising again in 1910-1911 as the cork-centered ball was introduced. Nine times between 1901 and 1909, and 13 times between 1901 and 1919, league leaders failed to crack double figures.

What separates Odwell from those other deadball sluggers is that he lasted only four years in the big show, despite being consistently praised for his all-around play. “No player that ever donned the red grasped affairs in the outfield with greater intelligence than Fred Odwell,” the Cincinnati Enquirer declared within months of his debut. “Possessed of clear eye, active brain and superb whip, Odwell is the ideal student of the game. … He ‘lays’ for the opposition in places to which the ball is most apt to be driven [and] … he has the baserunners of the enemy terrorized.”2

Sportswriter Ren Mulford Jr. called him the Human Greyhound.3 When all games were played in the daytime and weekday games generally started in late afternoon, Odwell was also valued for his skill at playing the sun field.4 If his game had a weak link, the writers agreed, it was batting. Odwell is almost certainly the only player who ever led his league in home runs, then apologized for his disappointing season.

Frederick W. Odwell, often called Fritz or Oddie, arrived in Cincinnati without fanfare in 1904 as a 31-year-old rookie. He stood 5-feet-9½ and weighed 160 pounds. He had broken into pro ball as a pitcher with control trouble,5 going 6-24 for last-place Wilkes-Barre in the Eastern League in 1897 before being moved to the outfield. Standard sources say he batted left-handed, but it’s likely he earned his long-ball laurels hitting as he threw, from the right side.

In his less-than-meteoric rise, he developed no reputation as a home run threat; records are incomplete, but Baseball-Reference.com shows him with just 20 homers in the minors through 1903. His power didn’t emerge immediately in Cincinnati, either. It was August 3 before he tagged his first and only home run of 1904, off Tully Sparks in Philadelphia. He completed the season with 22 doubles, 10 triples, 75 runs scored, and a highly respectable .284 batting average.

Of all the odd aspects of Oddie’s homer-happy 1905 campaign, one of the oddest is how late he got started. He didn’t record his first four-bagger until June 19, in the Reds’ 56th game and his 44th. By that time New York’s Bill Dahlen had five and his teammates Mike Donlin and Dan McGann had three each, as did Philadelphia’s Sherry Magee.

Once he got started, Odwell sprayed homers to all fields. He homered in six ballparks and against every opposing team except Pittsburgh. He homered three times in Boston, whose South End Grounds were one of the era’s more homer-friendly venues6 and whose pitchers led the league in home runs allowed three of Odwell’s four years with the Reds. He hit eight off right-handers and one off a lefty, seven on the road and only two at home.

Oddie hit four inside-the-park, including the two in Cincinnati. This was not surprising given Cincinnati’s huge outfield, with fences up to 450 feet from home plate; during the 10 years that configuration existed, barely 10 percent of all home runs went over the fence, and most of those did so on the bounce.7 Of the eight pitchers Odwell victimized, three were rookies and only one would complete his major-league career with a winning percentage above .500. That said, he caught two of the eight during their best season.

Victim number one was the most obscure of the lot. The Giants’ Claude Elliott was in his second and last big leagues season. The homer was “a terrific drive over [center fielder] Donlin’s head”8 on a sweltering day at Cincinnati’s League Park;9 Odwell “was so nearly overcome by the heat that he could hardly make it around the bases.”10 The eighth-inning solo blast capped the scoring as the Reds won 17-7. Odwell also singled twice and stole home on the front of a double steal. Elliott pitched in only 10 games in 1905 with an 0-1 record. Only decades after his death would somebody reexamine the record and discover that he also led the major leagues in saves that season, with six.

Odwell next struck on June 27 at Chicago’s West Side Grounds. The three-run shot came in the seventh inning and completed the scoring in a 6-0 Cincinnati victory. The ball sailed over the head of left fielder Frank Schulte “and rolled on and on to the far corner in left center where the clubhouse wall meets the left-field bleachers” more than 440 feet from home plate, “as long a hit as can be made on these grounds.” Fritz crossed the plate before the ball “got back to a point where it could be distinguished from a pea.”

Cincinnati sportswriter Jack Ryder, apparently believing that running should be a component of any proper home run, applauded “a clean home run, unaided by fence or barrier.”11 The pitcher was Bert “Buttons” Briggs, who had won 19 games for the Cubs in 1904. His five-year major-league career ended in 1905, when he had a modest 8-8 record. But his earned-run average was 2.14 and five of his victories were shutouts.

Odwell hit his third on July 14 in Boston. By now both Magee and McGann had hit their fourth. Coming with a man on and the Reds trailing 3-2 in the sixth, Odwell’s homer lifted Cincinnati to a 4-3 win. Descriptions of this one are somewhat difficult to reconcile. Where the Boston Globe said the ball “struck the top of the [right-field] fence and bounded over,”12 the Cincinnati Enquirer reported “the longest hit made on these grounds this year,” clearing the wall 30 feet fair – about 350 feet from the plate – and landing “beyond the streetcar tracks on Columbus Avenue.” 13 Pitcher Irvin “Kaiser” Wilhelm was suffering toward a 3-23 season for the Beaneaters, who would lose 103 games and finish seventh.

This time Odwell connected again just four days later on July 18. His solo homer in the ninth inning at Philadelphia’s Huntingdon Street Grounds (later renamed the Baker Bowl) tied the score at 4-4; on a day when a thermometer placed in the center field grass registered 116 degrees, 14 both starting pitchers went 14 innings before the Phillies’ Bill Duggleby secured a 5-4 verdict over the Reds’ Bob Ewing.

The home run initially looked like a routine single or double to right-center field. But according to eyewitnesses from both cities, the ball seems to have defied gravity. One account said that after hitting the wall, the ball “bounded up into the bleachers.”15 Another said it “ran up the brick barrier like a squirrel.”16 It was that kind of year for Bill Duggleby. Though he won 18 games, he also led the major leagues in home runs allowed with 10.

After that it was a month before Odwell homered again. By the time he notched his fifth in Boston on August 17, Bill Dahlen had pushed his league-leading total to six. Odwell’s latest went over the short left field fence (250 feet down the line) with the bases empty in the seventh inning. Coming off lefty Irv “Young Cy” Young, it gave the Reds a 5-1 lead; they won 5-3. Considering Harry Steinfeldt’s earlier two-run homer to practically the same spot, a Boston writer concluded that “the visitors won the game by virtue of the fence.”17 Young, a rookie, led the league in starts, complete games, and innings. The workhorse of a team that barely avoided last place, he managed a 20-21 record, best of his six-year career.

Next day the two teams engaged in a “batting carnival,”18 combining for seven home runs in a doubleheader as Odwell moved into a tie for the league lead. Again his shot, in the fourth inning of the second game with a man on, cleared the left field fence. Again the victim was the luckless Kaiser Wilhelm. After dropping the first game, Cincinnati won the second 8-7 when Odwell scored after tripling off relief pitcher Dick Harley in the tenth.

On August 28 Dahlen homered for the seventh time, pulling ahead in the home run derby. Odwell caught up the next day, belting one “high over the right-field fence”19 at Brooklyn’s Washington Park. The hit, off Fred Mitchell with the bases empty in the sixth, helped the Reds to a 7-3 win. Teammate Cy Seymour, in a season when he led the league in nearly every major offensive category, also notched a four-bagger, his fourth. This was the only time he and Odwell ever homered in the same game. The game was the last Mitchell pitched in the big leagues, although he later made a comeback and caught 62 games for the New York Highlanders in 1910.

Odwell finally took the lead on September 4. His eighth of the season was “a murderous line slam to deep left”20 in the first game of a doubleheader at Robison Field in St. Louis. The two-run clout gave the Reds a 2-0 lead in the fourth inning but the Cardinals struck for seven in the seventh and won 9-2 en route to a sweep.21 The pitcher was rookie Jake Thielman, who netted half of his ca-reer wins in 1905. He stuck in the majors through 1908, compiling a 30-28 record.

Our man didn’t connect again until the next-to-last day of the season, but he was never headed. Dahlen, who led the way for most of the season, struck for the last time on August 28 and finished with seven. That total was matched by Mike Donlin, who collected his last on October 6, and Brooklyn’s Harry Lumley, who arrived late at the party but moved into contention with five homers between August 26 and September 16. Seymour, another latecomer, homered five times in the last five weeks of the season and finished second to Odwell with eight. In the American League, the Philadelphia Athletics’ Harry Davis led the parade with eight.

Odwell’s final home run, the exclamation point on his season, was a drive “to deep center” off Buster Brown. It came with a man on in the eighth inning of the second game of a home doubleheader against St. Louis on October 7, sealing a 6-3 win and giving the Reds a split of the twin bill.

In this article we’ve viewed the season as a race for the National League home run title, but no one was tracking the chase at the time. Cincinnati correspondent C.J. Bocklet’s dispatches to The Sporting News rarely mentioned Odwell and unlike today, when updated statistics from around the league are available almost instantaneously, sportswriters had no convenient way of keeping up with players outside their own cities.

The Cincinnati Enquirer covered baseball as extensively as any local newspaper in the country. But when the 1905 season concluded the Enquirer could report only that, based on its own unofficial statistics, Odwell had “possibly” led the National League in home runs.22 In any case, the home run leadership wasn’t viewed as a big deal. When the league’s official stats were released, the version published in The Sporting News included columns for stolen bases and sacrifice hits but none for doubles, triples, or home runs.23

Odwell’s achievement – his sole claim to baseball fame – was acknowledged in the ninth paragraph of a Ren Mulford column in Sporting Life,24 but apparently it was never mentioned in TSN until it provided the lead to Odwell’s obituary in 1948. At that time a weekly paper near his home in Downsville, New York, attempted – with some exaggeration – to put his feat into perspective. “Those were the days of the greatest pitching ge-niuses the game has known, and before the advent of the lively, hopped-up ball,” the writer explained. “A home run was a sensational thing, calling for headlines.”25

In fact, some newspaper accounts in 1905 noted Odwell’s home runs only in the box scores. In an era when standard baseball tactics mostly fell under what is now somewhat dismissively called “small ball,” Odwell’s prowess as a slugger made little impression on Reds manager Ned Hanlon. While Odwell hit one homer while batting third and another batting fifth, most of the time Hanlon batted him sixth or seventh. All most observers noticed about Odwell’s stickwork was that his batting average dropped from .284 in 1904 to .241 in 1905. The player felt obliged to offer an explanation.

“It wasn’t my batting eye that went wrong. … It was my left leg,” he said. “Why, there were times when every time I came down hard on that pin it felt like when a fellow jars the funny bone in his arm. … Sometimes when I was running round the bases it would feel like I hadn’t any left foot at all.” Odwell blamed a torn tendon.26 In fairness, this wasn’t some sort of after-the-fact alibi. Mulford had reported six weeks into the 1905 campaign that Odwell had hurt himself on Opening Day “when he caught the spike of his left shoe in one of the drainage lids in the outfield,” then aggravated the injury three weeks later sliding into third base.27 He was out for two weeks before returning to the lineup on June 3.

Less than two weeks into the 1906 season, Odwell ran into his old friend Buster Brown, who delivered “a swift, quick-breaking inshoot” that caught Odwell below the heart.28 He suffered a cracked rib and was out for three weeks. While he was recuperating the Enquirer’s Ryder reported, as if it were a new development, that Oddie was “batting left-handed these days, and will continue in that style.” The change was viewed as a way to help Odwell beat out bunts and infield hits.29 It might also have offered some protection for the injured rib. Regardless, he never got untracked and as mid-season approached he was hitting .223. The Reds traded the erstwhile home run king along with pitcher Charlie Chech to Toledo in the American Association for outfielder Frank Jude.

Odwell’s downfall, in the opinion of the Enquirer, was “a weak style at the bat.” The writer – presumably longtime baseball specialist Ryder – lavished praise on all other aspects of the player’s game: “Odwell is as fast and clever an outfielder as can be found in the country today. He has a remarkable whip, and uses the best of judgment, both in fielding and throwing. He is a fine baserunner and a sensible man on the coaching lines. In addition … he is an admirable character personally … who always places the interest of the team above everything else.” But none of that could outweigh the fact that “his swing is so long that he has to start it before the ball is anywhere near the plate, and, as a result, he is often fooled by a curveball.”30

Odwell hit .306 (with five home runs) for Toledo and the Reds – with Hanlon expressing the hope that he had overcome his weakness against the curve – gave him another shot in 1907. He batted .270 in 94 games and was said to have “improved wonderfully,”31 but he went down with another leg injury – possibly a pulled muscle – late in the season. The Reds sought waivers on him in December and ultimately released him to Columbus in the American Association.

After his ninth and final homer in 1905, Odwell amassed 481 more major league at-bats but never hit another home run. He retired with a career total of 10, the lowest of any single-season leader since 1891. Charles “Count” Campau, who led the American Association – then a major league – in 1890 with nine, also retired with 10. So did Levi Meyerle, who shared the National Association lead with four in 1871. Campau’s big league career consisted of a mere 147 games between 1888 and 1894. Meyerle played in the National League in 1876-77 and in the Union Association in 1884 but hit all his home runs in the National Association from 1871 to 1875.

The only home run champ with fewer career homers than Odwell is Fred Treacey, who shared the NA title with Meyerle (and Lip Pike) in 1871. Treacey’s home runs – a total of seven – all came in the NA between 1871 and 1873.

Nobody remembers Fred Treacey either.

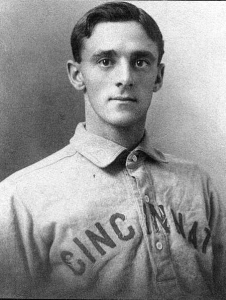

Photo Credit

Fred Odwell, courtesy of the Colchester Historical Society.

Notes

1. Bill James, “Reflections of a Megalomaniac Editor,” Baseball Analyst, Volume 35 (April 1988): 19.

2. “All Sorts,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 28, 1904: 30.

3. Ren Mulford Jr., “The Human Greyhound Tells of Suffering in Silence,” Cincinnati Post, May 24, 1905: 6.

4. Jack Ryder. “Notes of the Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 17, 1906: 4.

5. H.G. Merrill, “Odwell’s Career,” The Sporting News, August 27, 1904: 7.

6. From 1904 to 1907, Odwell’s years with the Reds, the South End Grounds yielded 112 home runs, a total exceeded in the NL only by New York’s Polo Grounds. No other park in the league saw more than 81. Bill James, John Dewan, Neil Munro and Don Zminda, eds., STATS All-Time Baseball Sourcebook (Skokie, Ill.: STATS Inc., 1998): 100-12.

7. Ronald M. Selter, Ballparks of the Deadball Era: A Comprehensive Study of Their Dimensions, Configurations and Effects on Batting, 1901-19 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008): 77. Batted balls that bounced over the fence counted as home runs until the rule was changed in 1931. See Bob McConnell and David Vincent, eds., The Home Run Encyclopedia: The Who, What, and Where of Every Home Run Hit Since 1876 (New York: Macmillan, 1996): 4.

8. “Reds in Third Place; Win From Giants,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, June 20, 1905: 6.

9. Though the ballpark where the Reds played from 1902 to 1911 is commonly referred to today as the Palace of the Fans, that name at the time properly applied only to the ornate main grandstand. See for example Ren Mulford Jr., “Redland is Dazed,” Sporting Life, April 25, 1903: 3: “The Palace of the Fans … and all other stands inside League Park were packed.”

10. “Smashed,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 20, 1905: 4.

11. Ryder, (headline missing), Cincinnati Enquirer, June 28, 1905: 4. The two-story clubhouse in cen-ter field was a new feature of the West Side Grounds in 1905. See Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Company, 2d ed., 2006): 50.

12. “Triple Play,” Boston Globe, July 15, 1905: 3.

13. Ryder, “Duplicated the Boston Triple Play,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 15, 1905: 3.

14. Ryder, “14 Innings in the Sun,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 19, 1905: 4.

15. “Phillies Won Out in 14th Inning,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 19, 1905: 13.

16. Ryder, “14 Innings.”

17. “Young ‘Cy’ Must Bow to ‘Spit-Ball’ Ewing,” Bos-ton Herald, August 18, 1905: 8.

18. “Batting Bee in the National League,” Boston Herald, August 19, 1905: 5.

19. “Minus Their Leaders Reds Break the Streak,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, August 30, 1905: 6.

20. “Big Holiday Crowd Sees Cardinals Win Two Bouts,” St. Louis Star-Chronicle, September 5, 1905.

21. Odwell’s home run log at Baseball-Reference.com says this home run bounced into the stands. None of the newspapers consulted for this article – four from St. Louis and four from Cincinnati in addition to Sporting Life and The Sporting News – mention that. The two most detailed descriptions suggest that Odwell had to run for the homer, indicating that the ball remained inside the park. One said that after hitting the ball, Odwell “started a sprint, which landed him across the plate.” The other said he made “an easy trip around the pillows, with [teammate Harry] Steinfeldt skedaddling in front of him.” See “Cardinals Continue Winning and Cincinnati Twice Falls Victim,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 5, 1905; and “Big Holiday Crowd Sees Cardinals Win Two Bouts,” St. Louis Star-Chronicle, September 5, 1905.

22. “Last Batch of Red Averages,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 10, 1905: 4.

23. “National Leader,” The Sporting News, October 28, 1905: 2.

24. Mulford, “A Red Desert,” Sporting Life, October 21, 1905: 3.

25. “Fred Odwell, Old-Time Big Leaguer Died Thursday,” Margaretville Catskill Mountain News, Au-gust 20, 1948: 1.

26. “Gossip of the Players,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1906: 4.

27. Mulford, “The Human Greyhound.”

28. Ryder, “Notes of the Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 25, 1906: 4.

29. Ryder, “Champs of the Wide, Wide World,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 12, 1906: 3.

30. “All Sorts,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 22, 1906: 30.

31. “Reds Must Have a New Manager,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, September 22, 1907: 17.