Sandy Koufax and Walter Alston: A Star Pitcher and his Manager

This article was written by Byron Petraroja

This article was published in Sandy Koufax book essays (2024)

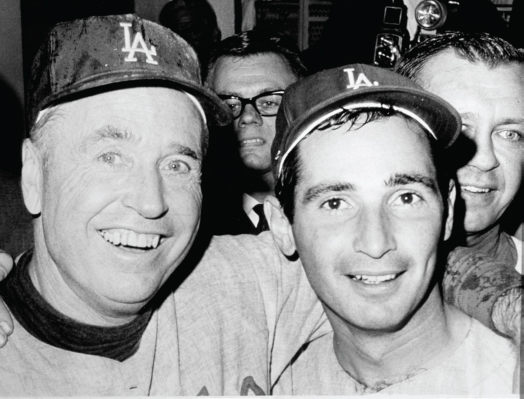

Dodgers manager Walter Alston celebrates with his Hall of Fame left-hander, Sandy Koufax. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

Sandy Koufax and Walt Alston will forever be linked in the minds of baseball fans, especially those who consider themselves to be close observers of the national pastime. One was a ferocious competitor who drove himself beyond reasonable thresholds of endurance and pain. The other, nicknamed “the quiet man,” was a fiery competitor in his own right, bubbling beneath the surface. Many questions have risen pertaining to the nature of their relationship; the task here is to shed light on this topic and perhaps to stimulate further inquiry.

While Koufax was attending Lafayette High School in Brooklyn, baseball scouts began to show guarded interest in him as he distinguished himself with the Parkviews, a team in the Coney Island League. Joe Labate, a scout from the Philadelphia Phillies, offered Koufax a contract for $1,500 to play in a college league in northern New York state. Koufax made it clear that he wanted a bonus large enough to allow him to pay for college if he found that he wasn’t talented enough to make it as a big-leaguer. At this point, he began to realize that a future in baseball might be a possibility.

By the time Koufax graduated from Lafayette High, he had developed into a skilled basketball player through many hours of practice, league games, and pickup games in both the school gymnasium and the Jewish Community House.1 His parents had clearly communicated to Koufax and his older stepsister that they were expected to go to college; Koufax agreed. Although he hadn’t been able to gather any feelers as far as scholarships were concerned, with the aid of letters of recommendation from both his high school and JCH coaches, he was invited to the University of Cincinnati, where he could work out with the basketball team. This workout, which amounted to a tryout, earned Koufax a scholarship offer.

As fate would have it, the basketball coach at the University of Cincinnati also happened to be the varsity baseball coach, and Koufax found himself as a Bearcats pitcher. He experienced enough success to attract scouts. The New York Giants offered him a tryout at the Polo Grounds, which apparently did not produce rave reviews and he never heard from them again. The New York Yankees made him an offer that didn’t include a bonus and was for a Class-D club. The Pittsburgh Pirates stepped forward but never made a concrete offer. The Brooklyn Dodgers and Milwaukee Braves were also expressing interest, which made for a frenetic schedule of traveling and tryouts.

The Dodgers appeared to express the most interest. Of note, Al Campanis, Brooklyn’s director of scouting, had a friendly rivalry with Branch Rickey, the executive vice president and general manager of the Pirates, and the former general manager of the Dodgers. Campanis thought that the Pirates were still very much in the running for the teenage pitcher. Koufax worked out with the Dodgers at Ebbets Field in the early fall of 1954 with Walt Alston, the Dodgers manager, also watching.

Walt Alston paid his dues during his climb to the major leagues. From 1940 through 1953, he worked his way up the minor-league managerial ladder. After observing the divergent paths Koufax and Alston took to the major leagues, it may not be too much of a stretch to think that Alston might want Koufax to prove himself before placing his trust in him as reliable member of his pitching staff. With Koufax having the “bonus baby” designation, the Dodgers were required to keep him on the major-league roster for two seasons, which essentially placed him ahead of several more experienced pitchers who were doing their time in the minors, just as Alston had done. Dick Young of the New York Daily News, in a column written June 14, 1956, referred to an overall lack of confidence Alston had in Koufax early in his career, writing, “A pitching pinch has to develop before Walt uses the kid. Then, it seems, Sandy must pitch a shutout or the bullpen is working full force and the kid will be yanked at the first long foul ball.”2

Based on comments he made in his autobiography as he thought back on his early years with the Dodgers, it appears that Koufax may have been frustrated by having been used sparingly. “I could be wrong. It could be argued, I know, that I was brought along slowly, nurtured carefully, and worked into the rotation when I was ready to put what I had learned to use. The only thing is that you can never convince me of it.”3 At other times however, he seemed to appreciate the predicament of his manager: “I needed experience, I needed work. Walt needed to win.” He went on to describe an incident in which he clearly lost his focus and failed to cover first base while pitching on the next to last day of the 1955 season. He was resigned to not getting a chance to pitch in the World Series that year. He conceded, “Any pitcher who doesn’t have the basic reflexes to break for first base on a ground ball hit toward the right side of the diamond can hardly be looked upon as a World Series pitcher.”4

After his first three seasons, Koufax’s record stood at 9 wins and 10 losses; hardly one that inspired his manager to view him as a pitcher he could depend on when games were up for grabs. In 1958, the Dodgers’ first season in Los Angeles, he went 11-11 with a 4.48 ERA, and 8-6 in 1959, when the Dodgers won the World Series in a season that provided many opportunities for a young pitcher to prove his worth. Koufax’s co-author wrote that Alston remained confident Koufax could indeed develop into a reliable pitcher: “Alston however, refused to quit on Koufax. The skipper’s attitude toward his young lefty had changed since ’56, and despite Koufax’s control problems, Alston gave him three straight starts in mid-June [of 1959].”5

Koufax rose to his manager’s challenge. On June 22, 1959, he struck out 16 Philadelphia Phillies, pitching a complete game and leading his team to a 6-2 victory. Koufax was given the start in a key August 31 game against the San Francisco Giants. He responded in magnificent fashion, fanning 18 and breaking Dizzy Dean’s National League record of 17 strikeouts and tying Bob Feller’s major-league record of 18 by striking out the side in the ninth inning. He started Game Five of the World Series, a potential Series clincher for the Dodgers. Although he couldn’t seal the deal, he held Chicago’s “Go-Go” White Sox to just one run over seven innings.

When Koufax finished the 1960 season with an 8-13 record, his frustration had reached the level that he was strongly considering quitting baseball to focus on other pursuits. In another book he related an incident in which he threw some of his equipment into the trash and told Dodgers clubhouse manager Nobe Kawano not to bother storing any of his possessions when the season had concluded. “It wasn’t that I had any regrets over the choice I had made. It was just that, having given myself six years, a full apprenticeship, I was convinced that the time had come to admit to myself that I wasn’t going to make it.”6

Koufax may have been more frustrated with himself and his own lack of progress than with Alston. He had been given multiple opportunities to learn the craft of pitching: “It wasn’t that I hadn’t gotten my chance to pitch in 1960, either, I had been given more chance than ever.”7 He was questioning his ability to master the all-important ability to control where his pitches were headed. Koufax was fully aware of this issue, having seen many pitchers who seemed very hittable but could make hitters look silly by exhibiting impeccable control.

Koufax ultimately decided to give baseball one last try as he entered the 1961 season with the attitude that if he was going to make it, he needed to fully commit himself to baseball. It didn’t hurt that he came into camp in the best shape of his life, having lost some unneeded weight which he attributed to having his tonsils out and not being able to eat or drink comfortably for two weeks. At least two other factors turned the tide in Koufax’s favor that year: He paid particularly close attention to the information the team statistician, Allan Roth, gave him about the importance of getting ahead of the hitter. And he heeded the advice of his roommate, catcher Norm Sherry, who encouraged him before a B-squad spring-training game to be a pitcher instead of a thrower. “You haven’t a thing to lose because none of the brass is going to be there,” Sherry told him. “If you get behind the hitters, don’t try to throw hard, because when you force your fast ball you’re always high with it.”8 Even though he had heard this type of advice many times before, Koufax finally absorbed it. Something clicked in that game and success followed. The 1961 season saw Koufax sprint out to a 10-3 record by the halfway point of the season and earn a spot on the National League All-Star team. By the end of the season he had won a career-high 18 games against 13 defeats and had broken the National League strikeout record, fanning 269 batters.

Koufax experienced his first significant injury during the 1962 season. He was cruising along with a 14-5 record in late July when he was forced to leave the rotation with a serious circulation issue in his left index finger. He came back in late September as his team was battling the San Francisco Giants for the pennant. However, he was largely ineffective in his return and the Giants edged out the Dodgers by taking a three-game tiebreaker series two games to one. Alston’s patience with Koufax had paid off, however, as Koufax had developed into a dominant pitcher, one of the stalwarts of the Dodgers staff.

Some might say that Alston’s trust and respect for his star pitcher had increased to a fault while Koufax developed into the player he had shown the potential to become. There are numerous examples of Alston leaving Koufax in a game when the situation seemed to dictate taking him out, as well as times in which he pitched him on short rest even though the health of his precious left arm was in question. For example, Alston gave Koufax the start on May 30, 1962; it was the Dodgers’ first return to New York since their move to Los Angeles. In the ninth inning, with the Dodgers holding a 13-6 lead over the New York Mets, Koufax had given up four hits in the inning and Alston let him stay in the game.

In late May of 1964, Alston brought in Koufax to pitch in relief on two days’ rest when just a month earlier he was out of the lineup with an ailing elbow. For Game Seven of the 1965 World Series against the Minnesota Twins, Alston was faced with the choice of pitching Koufax on two days’ rest or starting his other ace, Don Drysdale, who had an additional day of rest. He went with Koufax. Sandy was laboring in the fifth inning after giving up a solid double and a walk and appeared to have only his fastball at his disposal. Alston left him in the game even though Drysdale was warmed up. Koufax rewarded his manager’s trust by retiring the Twins and pitching a Series-winning shutout.

Despite the general belief by many observers that Alston had at times misused Koufax, it doesn’t appear that Koufax felt that way. Referring to his desire to pitch during the 1962 season with an injured index finger, he seemed to appreciate these opportunities. “I had spent too much of my life not pitching to think about missing any turns,” his autobiography said.9

There were indications that the relationship between pitcher and manager may not have always been smooth. Michael Leahy in his book The Last Innocents related an incident in which Maury Wills overheard a confrontation between Koufax and Alston concerning a change in the pitching rotation, Wills described the situation: “[Koufax] was raising hell. There was a lot of shouting between the two of them. Alston basically said, ‘Goddammit, I’m the manager.’ And Sandy yelled, ‘I’m the starting pitcher.’”10 The confrontation ended at that point as the room fell silent with Koufax emerging from the office.

Another incident involved a brief conversation between Dick Tracewski, a Dodgers infielder, and Koufax in which Tracewski commented on how Alston had relayed his decision to use Koufax over Drysdale to start Game Seven of the 1965 Series. Alston had apparently told the players that he would “start the left hander” and Tracewski felt that Alston’s choice to not use Koufax’s name was significant. “That rubbed Sandy the wrong way,” said Tracewski. Leahy wrote that Tracewski “believed that Koufax regarded Alston’s announcement as yet another slight in a relationship that wasn’t going to be warm and fuzzy ever.”11

Koufax gained his manager’s trust over time and Alston appeared to develop faith in Koufax. Alston and Koufax may not have had the closest of relationships. There were times when Koufax was frustrated with not being given enough opportunities to pitch early in his career and from time to time disagreed with Alston’s decisions. Perhaps, though, the ways in which they related to each other were more a product of their personalities. Some of these traits may have been ones they shared. Alston enjoyed some of the simpler pleasures of life; in his autobiography, A Year at a Time, he expounded on the value he placed on being back home in Darrtown, Ohio. “Back behind the barn there were woods of thirty or forty acres. … I loved to ride those woods, and Dad often went with me. The owners didn’t object and I’ve spent many an hour enjoying the quiet and solitude there.”12

Author Gruver cited former Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi, who spoke of how Koufax’s interests were different than those of the typical ballplayer and, respecting Koufax’s privacy, said, “I think few ball players had the same interests as Sandy. I don’t think too many players had an interest in music, in lectures, or doing some work around the house. Sandy was a loner in that respect. And you never wanted to pry with Sandy, so I never got too close with him.”13

Gruver used the adjective “phlegmatic” to describe Alston when the Dodgers hired him as their manager in 1954; in addition, he received the nickname “The Quiet Man” somewhere along the way. Alston, however, wrote, “[E]veryone who knows me well realizes that I’m slow to anger but, once I boil–watch out, it’s pretty hard to calm me down.”14

Koufax had his moments as well; Gruver described one of Koufax’s challenges as being one of overall self-control, “Even in his great years, he grimaced in disgust following an ill-timed hit or a walk. At times, he kicked the sheet metal on the bottom of the dugout water cooler in anger over a poor pitch.”15 Some of Koufax’s teammates, Wills for example, talked about how serious and nontalkative he became when it was time to prepare for a game even during spring training. “Other guys would be looking to have a little fun sometimes. … Not Sandy. All business.” Jeff Torborg talked about wanting to communicate with Koufax to make a good impression as his catcher; however, the exchanges between them were typically short and to the point.16 Between Alston’s stoic, calm persona with the potential to erupt and Koufax’s desire for privacy, his serious approach to the game, and also with that potential to unleash his fury at times, one can see how a close relationship between the two might never have had a chance to develop.

There were times, though, when Koufax and his teammates were involved in rather comedic situations with their manager. One such incident occurred when Sandy and fellow pitcher Larry Sherry wanted to celebrate a little after each had pitched extremely well during spring training in 1961. They went out and when they returned, they had broken curfew and were loud enough to alert their manager to their transgression. Both Koufax and Sherry slipped into their rooms just before Alston came charging down the hall. When he arrived at Sherry’s room, he found it locked and began hammering on it with his fists. In doing so, he managed to break his diamond-studded World Series ring. Both players were fined $100, and the rest of their teammates found the whole thing hilarious.17

There are some indications that Walt Alston wasn’t one to play favorites and for the most part had the same expectations for all the players he managed. “I’ve always believed that baseball is still a game,” his book said. “You ought to enjoy, get some fun out of playing, yet give it everything you have. As long as I could get that out of a player I was pretty easy to get along with.”18 If you didn’t meet those expectations, however, you would potentially be introduced to Alston’s wrath. Leahy described an incident in which Lou Johnson, a Dodgers outfielder, was late for batting practice before the seventh game of the 1965 World Series and how angry that made Alston. “Johnson had never seen Alston so upset,” Leahy wrote. “That the two men got past the moment had less to do with anything Johnson said than it did with Alston’s utter lack of choices.”19 The Dodgers had a dearth of power that season, and Alston needed Johnson’s bat in the lineup.

Alston talked about the challenge he faced with being close with his players. He referred to one of his former players and coaches, Tommy Lasorda, who felt that Alston was becoming less close to his players. Alston explained the reason as being basic geography, “no doubt part of that comes from being older and more experienced as a manager. And the mere fact that in Los Angeles we’re spread out over half of Southern California rather than living within a few blocks of Dodger Stadium makes it hard to be close.” However, he described how his Montreal Royals ballclub from years earlier was “a tight little clique,” in part because most players did not speak French and tended to socialize with one another.20 It seems that Alston genuinely enjoyed down time with family members, other members of his staff, and players, as he talked fondly of playing cards with them during road trips: “During the years when Don Drysdale, Jim Gilliam and Wes Parker were playing for us we played a lot of bridge on the road. But in recent years we just haven’t had four bridge nuts on the club.”21

Both pitcher and manager shared a high level of competitiveness that fueled their drive to succeed. Over the course of their careers, each had a strong impact on the overall success the other experienced. After all, both Koufax and Alston were inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame–Alston in 1983 and Koufax in 1972. Perhaps this comment by Alston encapsulates how he truly felt about his star pitcher:

“You’d need a book or two to recite all of Sandy’s accomplishments. His greatest was himself. He worked tirelessly to achieve success. Once he did he was no different from the Sandy who came to Ebbets Field in 1955 [sic] to try out. He was team-oriented, took coaching well and worked hard.”22

is a retired Syracuse city public-school teacher and a current SABR member. During the early stages of his teaching career, he was introduced to the field of storytelling and has since told stories in the classroom and at various community settings including the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. This is his initial experience as a contributor to a SABR book project and he has thoroughly enjoyed the process.

NOTES

1 The Jewish Community House is on Bay Parkway in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn. It was founded in 1927 and as of 2024 still existed. It has always served as a place for the Jewish community and their neighbors to gather and support each other during times of need. (JCHB.org).

2 Edward Gruver, Koufax (Latham, New York: Oxford, Taylor Trade, 2000), 119.

3 Sandy Koufax with Ed Linn, Koufax (New York: Viking Press, 1966), 114.

4 Koufax with Linn, 105.

5 Gruver, 121.

6 Koufax with Linn, 143.

7 Koufax with Linn, 143.

8 Koufax with Linn, 154.

9 Koufax with Linn, 165.

10 Michael Leahy, The Last Innocents (New York: HarperCollins, 2016), 226.

11 Leahy, 320.

12 Walter Alston, A Year at a Time (Waco, Texas: World Books, 1976), 76.

13 Gruver, 172.

14 Gruver, 173.

15 Gruver, 4.

16 Leahy, 197.

17 Koufax, 155.

18 Alston, 87.

19 Leahy, 322.

20 Alston, 88.

21 Alston, 100.

22 Alston, 164.