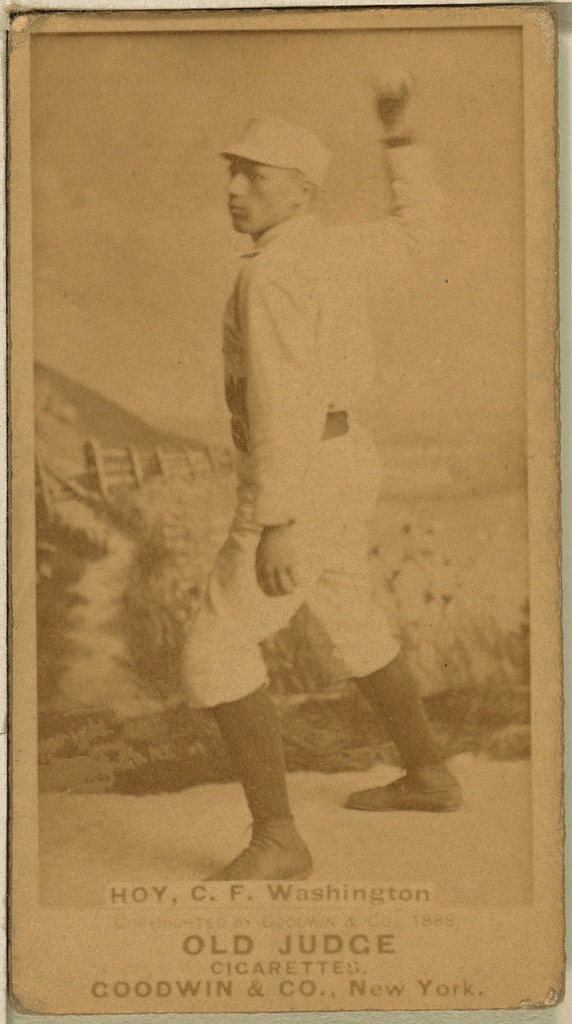

William Ellsworth Hoy, 1862-1961

This article was written by Joseph Overfield

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 2, 1983)

Back in 1955, while searching the old newspaper files at the Buffalo Historical Society, I came across a photograph of the 1890 Buffalo Players League team, from which I was able to have copies made. At the time, surprisingly, two members of the team, Connie Mack and Dummy Hoy, were still alive. I wrote to each of them, enclosed a picture and asked some questions about that ill-starred Buffalo club, one of the most inept in baseball history, finishing in eighth place, 20 games out of seventh.

Back in 1955, while searching the old newspaper files at the Buffalo Historical Society, I came across a photograph of the 1890 Buffalo Players League team, from which I was able to have copies made. At the time, surprisingly, two members of the team, Connie Mack and Dummy Hoy, were still alive. I wrote to each of them, enclosed a picture and asked some questions about that ill-starred Buffalo club, one of the most inept in baseball history, finishing in eighth place, 20 games out of seventh.

I received a short, rambling note from Mack, who was then ninety-two. The venerable one thanked me for the picture, answered none of my questions and concluded by writing, ”You must be very old to remember Deacon White.” (I was thirty-nine at the time.) Properly humbled, I awaited with some trepidation a reply from Mr. Hoy, who was just three months younger than Mack.

When Hoy’s letter came, it put all my fears to rest. Datelined, most appropriately, Mt. Healthy, Ohio, November 15, 1955, the letter was six pages in length and written in a bold, unquivering, and beautiful hand that completely belied the age of the writer. All of my questions were answered in sentences that were grammatically pure and perfectly punctuated.

Those of us who are inveterate letter writers sometimes gain rich rewards. This was such a time.

I was to exchange many letters with Hoy. The last one I received from him was dated January 3, 1961. He was ninety-eight then, and it was just eleven months before his: death on December 15, 1961, five months and eight days short of his 100th birthday. He had lived longer than any other major league ballplayer.

I never met Hoy, other than through our letters, but I was fortunate enough to see him on television when he threw out the first ball at the 1961 World Series between Cincinnati and New York.

There was always some question about Hay’s true age. Some sources said he broke in with Oshkosh, Wisc., at age twenty, while later accounts reported him to be twenty-four when he made his debut. His reply to my inquiry about this discrepancy follows:

I will tell you how this happened [the discrepancy] and go bail on the correctness of my figures. They were copied from the family Bible!

One rainy day in the spring of 1886, the Oshkosh players were assembled in the clubhouse getting ready for opening day. A newspaperman entered to take down the age, height and weight of each player. When it came my turn to be interviewed, he omitted me because I was a deaf-mute. Also, he had not the time to bother with the necessary use of pad and pencil. When I read his writeup the next day, I found he had me down for twenty years of age. He had made what he considered a good guess.

Now in my school days, I had been taught to refrain from correcting my elders. Then too, he had whiskers! After thinking it over, I decided to let the figures stand. It was in this way that I became known as the twenty-year-old Oshkosh deaf-mute ballplayer. What would you have done if you were in my place?

However, later on, I was pinned down by an alert Cincinnati insurance man at the Methodist book concern where I was employed at the time. He told me to write down my full baptismal name, together with the day, month and year of my birth. Nobody had ever asked me such a question before. If they had, I certainly would have written down 1862 and not 1866.

In the Sporting News Record Book, Hoy is listed as the first outfielder to be credited with three assists from outfield to catcher in a single game. In a letter I received from Hoy in 1959, he recalled this feat:

The first putout was accomplished when a batter made a basehit to me in the outfield. The runner on second was put out by my throw to the catcher. The next out at the plate was made in the exact way as the first. The third play was a basehit over shortstop in about the eighth inning. I picked up the ball, threw to the catcher and caught the runner attempting to score from second. I had no other fielding chances whatsoever during the entire game, the three assists being all the chances I had. The game took place on June 19, 1888, and was a regularly scheduled National League game between Washington (my club) and Indianapolis, then a member of the National League. Do you know of any other player who duplicated this feat? Bear in mind the three assists were on basehits to the outfield. If you know of any, who is he? I want to shake his hand.

NOTE: Two other outfielders are credited with three assists to the catcher in one game. They are Jim Jones of the Giants on June 30, 1902, and John McCarthy of the Cubs on April 20, 1905.

The box score of the game from the Sporting Life substantiated Hoy’s recall in every detail. It was truly a remarkable performance, but just as remarkable was his perfect recall of it seventy-one years later.

Hoy played eighteen seasons as a professional, remarkable in light of his late start, his deafness, and his muteness. He was one of two deaf mutes to gain fame in the majors. The other was pitcher Luther (Dummy) Taylor, who won 117 games, all but 1 for the New York Giants, for whom he won 27 games in 1904. According to Daguerreotypes (Sporting News), Paul Hines, famed outfielder of the last century, was deaf. His deafness, however, did not develop until he was thirty-four after a beaning in 1886 by Jim (Grasshopper) Whitney of Kansas City; of course, he did not have the additional handicap of muteness. (Strangely, Hines and Whitney were teammates the next season at Washington.)

Hoy’s late start in the game may be attributed partly to his infirmity—which, incidentally, followed an attack of meningitis when he was three—but to a greater extent to economics. In an interview with Art Kruger for a publication called the Silent Worker and later condensed in the May 1954 issue of Baseball Digest, Hoy recalled that his father gave his sister a cow and a piano when she was eighteen, and to each of his brothers, when they became twenty-one, a suit of clothes and a buggy, harness, and saddle. When William reached majority, his father gave him only the suit, but promised him free board until he was twenty-four. “Being handicapped by deafness, it was my thought that I would make better progress in life if! worked as a cobbler and lived at home, rather than to accept the buggy, harness and saddle and leave home.” So, he recounted to Kruger, he opened a shoe shop in his native Houcktown, Ohio, after graduating from the State School for the Deaf at Columbus, where he had won highest honors and had been valedictorian of his class. Business was dull, especially in the summer when most everyone in Houcktown went around sans shoes, so there was plenty of time for William to play ball with the young men of the town. He told Kruger that a man from nearby Findlay noticed him one day and asked him to play a game in Kenton, which was a few miles away. He agreed and did so well against a former professional pitcher that he decided to give baseball a try.

Frank Selee, later to enjoy success as a major league manager, was the skipper at Oshkosh of the Northwest League in 1886 when Hoy signed his first contract. Selee was perspicacious enough to see Hoy’s innate ability and stayed with him that first difficult year, despite his .219 batting average. He improved next year to .367, stole 67 bases and led Oshkosh to a pennant. This performance earned him a promotion to Washington of the National League where he batted .274 and led the league in stolen bases with 82.

His career from that point on was peripatetic, to say the least. Besides Washington, he played for Buffalo, of the Players League, St. Louis of the then major league American Association, and for Cincinnati, where he starred from 1894 to 1897, only to be traded to Louisville. After two seasons with that National League club, he cast his lot with Ban Johnson’s fledgling American League, playing for Chicago in 1900 and then again in 1901, the AL’s first year of major league status. He returned to Cincinnati for a final major league fling in 1902, batting .259 in 72 games. He was one of twenty-nine men to play in four major leagues: National, Players, American Association, and American.

Hoy wound up his career in 1903 at Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League where he played in every one of his team’s 211 games. His average was a modest .261, but he totaled 210 hits and stole 46 bases, five more than his age.

At five feet, five inches, and 150 pounds, Hoy, who batted left and threw right, did not have the heft to be a power hitter, but he did get his share of doubles and triples and was an excellent baserunner. In the field his speed was an asset and he was considered to be a reliable fielder with a strong and accurate arm. Detroit writer H. G. Salsinger, quoting an old-time St. Louis Writer, Thomas Lonergan, wrote, “Hoy was the smartest player he had ever seen, swift as a panther and very fast in getting the ball in from the outfield.” Of his throwing prowess there can be little question: witness his three assists to the plate previously described, and the fact that he was in double figures in assists every season except for 1902 at Cincinnati. His lifetime total (major and minor) was 389, including a league-leading 27 with Louisville in 1898 and an incredible 45 with the 1900 Chicago club.

It has been widely written that it was because of Hoy that umpires began to raise their right hands to signify strikes. Paul Helms—wealthy west coast businessman, founder of the Helms Foundation, and a nephew of Hoy’s—states this unequivocally in the Kruger article above mentioned. On the other hand, the authoritative Lee Allen, in his Hot Stove League, tells us that Charles “Cy” Rigler of the National League was the first to follow this practice, and he did not come into the league until 1905, two years after Hoy’s retirement. According to Allen, Cincinnati players used to signal strikes to Hoy in this manner.

How good a player was Hoy? It is the conclusion here that he should rank high, even meriting Hall of Fame consideration. Hall of Famer Tommy McCarthy, with whom Hoy is often compared, was a contemporary, playing from 1884 to 1896. The two were teammates at Oshkosh in 1887 and at St. Louis (AA) in 1891. A comparison of the two players’ major league records seems to indicate that Hoy has been overlooked far too long.

| Hoy | McCarthy | |

|---|---|---|

| Seasons | 14 | 13 |

| Games | 1798 | 1275 |

| At-Bats | 7123 | 5128 |

| Hits | 2054 | 1496 |

| Doubles | 248 | 192 |

| Triples | 121 | 58 |

| Home Runs | 40 | 44 |

| Runs | 1426 | 1069 |

| RBIs | 726 | 666 |

| Stolen Bases | 597 | 467 |

| Walks | 1004 | 537 |

| Batting Average | .288 | .292 |

| Putouts | 3932 | 2034 |

| Assists | 286 | 301 |

| Errors | 384 | 261 |

| *Fielding Pct. | .917 | .899 |

It is unlikely at this late date that Hoy will gain much Hall of Fame support, any more than will his teammate on the 1890 Bisons, Jim (Deacon) White, one of the truly great players of the game’s early years. But there can be no doubt that Hoy was an outstanding player, whose accomplishments loom even larger, considering he could neither hear nor speak.

*Hoy played 1797 games as an outfielder and one game at second base. McCarthy played 1189 games in the outfield, 39 at second base, 37 at third base, 20 at shortstop and 13 as a pitcher.