Bowing Out On Top

This article was written by James D. Smith III

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 2, 1983)

In the early months of 1926, Ty Cobb recounts in his autobiography, My Life in Baseball, the great outfielder was obliged to submit to eye surgery at the Johns Hopkins Clinic in Baltimore: “the dust of a thousand ballfields was in my eyes.” Shortly before he was admitted, a poem appeared in one of the local papers:

The curtain’s going to drop, old chap

For Time has taken toll,

And you could never play a part

Except the leading role.

You might go on and play and play,

But why go on for folks to say

“There’s old Ty Cobb, still on the job,

But not the Cobb of yesterday.”

The record shows that the Georgia Peach not only played that season, but added two more with the Philadelphia A’s before hanging up his spikes—batting over .300 each time. The point, however, is well taken: it has been said that, amid all the physical and mental exertion, the toughest thing for a ballplayer is knowing when to quit. And, as does no other sport, baseball often provides a decisive statistical indication of that moment when the sun has dropped below the horizon of a career.

The story is told of another Hall of Famer, Adrian (Cap) Anson, relating an incident which occurred a few years before his death in 1922. The old Chicago veteran was involved in a Windy City accident which nearly claimed his life. This prompted a close friend, half-jokingly, to ask what he would like as an epitaph when the time came for him to be laid to rest. With little hesitation, the reply came: “I guess one line will be enough-just write this on my tombstone: ‘here lies a man that batted .300.’” Pop Anson, of course, had finished his career on that note, batting .302 at the ripe age of forty-six.

But how many have gone out that way, clearing that time-honored barrier, satisfied with a strong effort at the plate during their final major league campaign? And, for those closing their big league careers in that manner, how was such a decision made—what marked the end? These two questions provide the starting point for a glance backward into a century of baseball history.

At the outset, four points must be made. As implied above, our investigation does not begin with any so-called “modern era” of baseball (1893? 1900? 1901? 1903?). In 1968, the Special Baseball Records Committee declared that major league baseball has been played in America since 1876. To approach completeness, even with changes in the game and some records still being researched, out story must begin at the beginning and recognize the continuities.

Second, since many players have appeared briefly for a “cup of coffee” on major league rosters, or played only occasionally, some criterion of involvement is necessary. For our purposes, the measure of a “regular” player is not number of games, but a number of plate appearances equal to 2.5 times the scheduled games.That is, for a 154-game season, 385 appearances provide a cut-off point; for 1877, when the schedule called for 60 games, the figure becomes 150 plate appearances.

Next, not all players end their careers voluntarily—some do; most don’t. (1) Some leave the game for health reasons. (2) A few have been permanently suspended—barred from major league ball. (3) Far more frequently, players have continued their careers in Organized Baseball by catching on with a minor league team. (4)

Finally, there is a story behind each of the thirty-six regulars who batted .300 in his last major league season; four of these—one from each of the categories listed above—will serve to epitomize the group. And within each group, four others will have their tales told in brief. Some players are familiar, others obscure-but all reach beyond the statistics to provide a brief glimpse of the wealth of baseball history.

Eight players played regularly in their final campaign, batted .300, and retired voluntarily from organized baseball.

Cap Anson has been mentioned above, retiring in 1897 after twenty-two legendary seasons with Chicago. In Anson’s obituary, Grantland Rice best summed up what lay behind his retirement: “The light in his batting eye was still carrying a bright glow when his ancient arms and legs had at last given away and ended his career upon the field.” His involvement with baseball was to continue in a variety of management and business ventures, including an unhappy stint as manager of Andrew Freedman’s New York Giants.

Bill Lange stands as the finest everyday, all-around player to retire from baseball at the peak of his career. Born in San Francisco, he developed there both his baseball skills and a lifelong attachment to the Bay Area. In 1893, aged twenty-one, he began his seven-season major league career with the Chicago Colts. By the time player-manager Anson retired, Lange was already being hailed by some as “the greatest player of the age.”

His physical tools were impressive. In an age of generally smaller players, he stood 6’2″ and weighed over 200 pounds. Moreover, he was lightning fast as a runner, as well as being agile in the outfield..

The 1897 season was vintage Lange. In the spring, he was helping to coach the Stanford baseball team. On March 5, he received a telegram summoning him to the Colts’ training camp in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Determined to remain in the West until local favorite Gentleman Jim Corbett’s fight with Bob Fitzsimmons in Nevada, his first stalling tactic was to send a wire refusing to report until he received a $500 raise. But the raise was quickly granted (provided he come immediately and tell no one of the bonus). The fight was scheduled for March 17. So he managed to “sprain his ankle,” wiring the news on March 12 that it should be all right in a week. It was (Corbett wasn’t), and Lange finally reported in time to hit .340 with 73 stolen bases.

More famous, however, was his 1896 campaign. Despite stealing 84 bases and batting .326, it was his fielding that would become legendary. Al Spalding, when selecting his all-time major league team years later, chose Lange even over Tris Speaker. “Both men,” he reflected, “could go back or to either side equally well. Both were lightning fast in handling ground balls. But no man I ever saw could go forward and get a low line drive like Lange.”

During the 1899 season, his last, a romance with Miss Grace Geiselman of San Francisco blossomed. After the campaign, wedding plans were made for the spring, and in October (with his fiancee in Europe) Bill Lange announced his retirement from baseball. He left to take up a position in a large real estate and insurance firm in his native city, accepting a partnership with his father-in-law to be.

In the following years, he played occasionally and became involved in scouting (sending nephew George Kelly to the majors) and in the business end of baseball in California. He died in 1950, mourned in his native San Francisco and by all in Chicago who ever saw him play.

Ty Cobb, after twenty-four seasons of American League baseball, issued a statement on September 17, 1928, declaring that he was in his final campaign: “I prefer to retire while there still may remain some base hits in my bat. Baseball is the greatest game in the world. I own all that I possess in the way of worldly goods to this game. For each week, month, and year of my career, I have felt a deep sense of responsibility to the grand old national sport that has been everything to me. I will not reconsider. This is final.” His aching legs and old wounds made his final season, the last of two under Connie Mack, “hellishly hard.”

Ted Williams, thirty-two years later, closed out his magnificent career with the Red Sox with a 425-foot home run at Fenway Park on September 28. Earlier in the season, after hitting his 500th home run, he had remarked: “I want to play out the year if I can. I hope I can get through it. I know I can’t play all the time. I need a rest about every fourth day. But I think I’ll be able to hit the rest of the year. I believe I can still help the club.” And hit he did, rebounding from his only sub-.300 season in a career which touched four decades. After his final game, in the dressing room: “I’m convinced I’ve quit at the right time. There’s nothing more I can do.” Except, perhaps, fish. . .

Lou Brock ended his stellar career with a major league record 938 stolen bases, 21 in his final season of 1979. In spring training he had declared, following a disappointing 1978, “I think this will be my last season in baseball. Even if present conditions change, I don’t think I want to go on. The mental tear is too much. The writing is on the wall . . . I am convinced that a real champ, a thoroughbred, can rebound. I’d like a chance to prove it.” In September, after he had collected hit number 3,000 the previous month and was still going strong: “The most important thing was to crown my career with a fine performance. I’ve always wanted to leave baseball in a blaze of glory.” He retired to become Director of Sports Programming for a Cable TV concern and to pursue other business and civic involvements.

*****

Four ballplayers ended their major league careers still batting a steady .300, but overcome by poor health, even death.

Dave Orr was the 250-pound first baseman on John M. Ward’s 1890 Brooklyn team in the Players League. In his eight major league years he never batted under .300-including a .373 mark in his final year—though often hit with nagging injuries. On July 12, he had two ribs broken by a pitched ball in a game against Boston. He continued to play for a time, but the pain continued. Late in the season, during an exhibition game in Renova, Pennsylvania, he was stricken with a paralysis which affected his whole left side. He hoped to find the therapy in Hot Springs, Arkansas, which would allow him to return in 1891, but he never fully recovered. He served in various positions attached to baseball, including a job as caretaker when Ebbets Field was being built.

With the exception of Lou Gehrig, perhaps the player best remembered for a career tragically halted by terminal illness is Ross Youngs. At 5’8″, he was stocky, powerful, and aggressive. College coaches pursued him for his abilities in track and football, but he wanted to play professional baseball.

Immediately after graduation, in 1914, he became a seventeen-year-old trying to hold his own in the fast Texas League. The Austin team let him go, and he drifted into lower leagues for two seasons. In 1916, however, he enjoyed a .362 campaign in Sherman, Texas of the Western Association-and his contract was purchased by the New York Giants. John McGraw brought him to spring training camp at Marlin, Texas, in 1917 but sent him to Rochester, bringing him back at season’s end to hit .346 in seven games.

That was the first of eight straight .300 seasons Youngs registered for the Giants, who captured National League pennants in 1921-24. For the first of these four pennant winners, he drove home 102 runs with benefit of only 3 homers. He was a “short Ty Cobb.” In the process, he also captured a spot in the hard-bitten McGraw’s heart reserved only for Christy Mathewson. The pictures of those two would adorn McGraw’s office wall for years to come.

In 1924, the Giants lost a hard-fought World Series to Walter Johnson and the Washington Senators. That winter, during a stay in Europe, Ross Youngs became ill, and carried the effects into 1925, in which he lost almost 100 points off his previous season’s average (.356-.264).

A cloud of uncertainty and concern hung over him at the Giants’ training camp. Youngs seemed sluggish and drained, somehow. When questioned, he laughingly replied, “I guess I’m getting old. It takes me more time to get in shape.” McGraw, however, was worried and depressed by all this (Mathewson had died in October 1925), and called in a doctor. He was told that “Pep” might not finish the season, that his condition would require a special diet and constant attention. “Muggsy” hired a male nurse to monitor his right fielder’s needs. Youngs was determined to play as hard as he could for as long as he could.

He joked about his male nurse and special care: “I used to laugh at Phil Douglas [the inebriate Giants’ pitcher] and his keeper—now I’ve got one.” He taught a seventeen-year-old rookie named Mel Ott to play right field. And, having played his final game on August 10, he closed his season at .306. He was no longer able to take the field, due to the progressive effects of Bright’s Disease, a degenerative kidney disorder which led to the retention of toxic uric acids. Despite the best care available in the 1920s, prolonged convalescence, and repeated transfusions, he died in San Antonio, Texas on October 22, 1927. He was thirty.

Perhaps the best summary of Youngs’ career is to be found in his eulogy by John McGraw, who had already managed the Giants for twenty-five seasons and whose baseball memory reached back to the Baltimore Orioles of the 1890s: “He was the greatest outfielder I ever saw. . . he was the easiest player I ever knew to handle . . . on top of all this, a gamer ball player than Youngs never played. . . . “

Ray Chapman is the only player to be killed by a pitched ball in the major leagues. On August 16, 1920, in the midst of the best of his nine major league seasons, he was struck in the head by a Carl Mays submarine delivery. One of the finest hitting and fielding shortstops in the American League, he remained conscious for a time but could not speak, passing away at 3 AM the next day.

Roberto Clemente ended his career in 1972, reaching the 3,000 hit milestone on September 30. Before the season began, however, his spring training interviews had told a story: “There is no way I can play more than this year and next year. No way.” Even as his hitting remained strong and he won his twelfth Gold Glove, it appeared that the 1973 season might well be his last. It never came. On the night of December 31 the airplane in which he was riding, carrying medicine and supplies to earthquake victims in Nicaragua, plunged into the Atlantic. Waiving the five-year wait, baseball writers voted him into the Hall of Fame in 1973.

Two other players, both .300 batters but neither surviving midseason, deserve brief mention. Ed Delahanty, the great turn-of-the-century slugger, died on July 2, 1903 when he plunged off a railroad bridge into the darkness of the Niagara River—a mysterious end to a remarkable career (he was batting .333 for Washington at the time and that was below par for him!) Lesser known, but a fine player at age thirty, was Pittsburgh first baseman Alexander McKinnon. Batting .340 coming into a game at Philadelphia onJuly4, 1887, “Mac” complained of not feeling well, and the next day was persuaded to go home to Boston: “I don’t believe I tried harder in my life to break a sweat than I did this morning, but it was no go.” He had typhoid fever, and died on July 24.

*****

Four seasoned regulars enjoyed campaigns well over the .300 mark, but never played another inning in the major leagues-banished from Organized Baseball for conspiring with gamblers to throw games for a payoff. The Black Sox scandal of 1919 immediately comes to mind—and, indeed, three of the plus-.300 group were mainstays of that team. The remaining figure, however, deserves special attention, as he played a vital role in what was baseball’s biggest scandal of the nineteenth century.

George Hall was born in Brooklyn in 1849, and polished his skills there during the baseball boom which followed the Civil War. There were no recognized professional teams or leagues in the mid-1860s. Amateur clubs and town teams had been in the field for decades, and as competition for the prestige and profit of a “winner” increased, under-the-table payoffs increased as well. Heavy betting and the periodic throwing of ballgames through intentionally careless play plagued the ballparks. Amateurism had become a sham—and into this turbulent atmosphere stepped a nineteen-year-old George Hall.

After an 1868 season with the Excelsior Juniors of Brooklyn, he caught on as first baseman for the Cambridge (NY) Stars, one of the leading teams in the East. In 1870, he returned to Brooklyn as center fielder of the Atlantics. But when the Atlantics decided to reorganize as an amateur club in 1871, Hall moved down the coast to play center field for the Washington Olympics of the new National Association of Professional Base Ball Players. He batted ,260, but was just reaching his physical maturity, standing 5’7″ and weighing around 140 pounds. (It should be noted that, of the 150 or so NA players for whom vital statistics are available, only about a dozen were known six-footers.) He was a wiry left-handed batter with sure hands, good speed, and surprising strength for his size.

In 1872, the Olympics dropped back to “cooperative” status in the league, indicating an economy operation with players paid from gate receipts without guarantee. Faced with this, Hall moved to nearby Baltimore to wear the silk uniform of the Canaries. He batted .300 and.320 in 1872 and ’73, but with the high expenses of a twelve-player roster, huge for that period, the team sank in red ink (in the latter season, Hall was the lowest-paid regular but drew $1000). The team scattered, and he joined Cal McVey in moving to the prestigious Boston Red Stockings-champions the past two seasons.

In Boston, though called a substitute, in deference to the legendary but aging Harry Wright, he played the latter’s traditional center field position in most of the league games (.329) and the several exhibitions. In July of that 1874 campaign, he enjoyed the team’s exhibition tour in England. For his season’s labors, however, he was paid only about $500. The following season, at age twenty-six, he signed with the Philadelphia Athletics.

The atmosphere in Philadelphia was significantly different from what he had known in Boston. The crowds were notoriously rowdy. Betting was heavier on games and innings, and the “baseball pools” were openly played on the premises. The undisciplined corruption which would eventually destroy the NA was rife in Philadelphia. During that season, Hall was also reunited with his tough, but moody, former teammate and manager in Baltimore, William Craver.

After some years of taking a brutal beating as catcher (with no protective gear), Craver had developed skills as a second baseman. He had also cultivated other skills: in August of 1874, he had been accused by Billy McLean, a former New York City bare knuckle fighter and widely respected umpire, of “throwing” a ballgame. During his 1875 season with the Athletics, the Brooklyn Eagle named a starting lineup of “rogues” who “would think only of how much money to make out of a game,” and included Craver without fear of a libel suit. By season’s end, the second-place Athletics were in financial difficulty and the fans were indifferent. The National Association itself collapsed, to be replaced by the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs.

In 1876, George Hall was stationed in left field for the reorganized Athletics and enjoyed his finest season, batting .366 and becoming the first NL home run king (5); the A’s, meanwhile, went 14-45 and, at the league meetings in December, were expelled for failing to play out their final scheduled games. Without a team, Hall signed with Louisville for the 1877 season, his last.

The Louisville Grays were a strong team. Holdover Jim Devlin was one of his era’s great pitchers, and in ’77 became the only one in major league history to hurl every inning of his team’s games. Hall joined a young and speedy outfield. The captain, however, was the aforementioned Bill Craver. And, when their third baseman developed a painful boil at midseason, Brooklyn native Al Nichols, who had batted .179 with a league-high 73 errors at that position for the 1876 New York Mutuals, was signed at Hall’s suggestion. The Grays were league leaders and favorites well into the campaign but suddenly began losing late-season road games in suspicious ways. Amid Louisville Courier Journal headlines like “!!!-???-!!!” and tips on gamblers’ betting patterns, club vice-president Charles E. Chase initiated an investigation which led to confessions by Hall, Devlin, and Nichols, backed by incriminating telegrams from New York gambling connections. The three were promptly suspended by the Grays, along with Craver, who had refused to have his telegrams opened and was generally uncooperative and antagonistic. In December, the league reaffirmed these suspensions, as did all the clubs of the newly formed “League Alliance.” Having batted .323 while appearing in all his club’s games, Hall was banished for life. St. Louis tried to sign him and Devlin to ’78 contracts, but to no avail.

Following the scandal, Hall began, by choice, to fade into obscurity. While Devlin and Craver made repeated appeals in person to league officials like president William Hulbert, Hall’s fruitless appeal for reinstatement in December of 1878 was made by mail. He may have played ball in Canada—Craver tried to and Devlin did. Other evidence remains inconclusive.

What is certain is George Hall’s eventual return to Brooklyn, where he labored quietly as an engraver for years. He died, at age 96, in 1945-unrecognized both as the last of the pre-National Association worthies and as one of baseball’s greatest wastes of talent.

Four decades later, eight Chicago White Sox players were banned from Organized Baseball for life for their part in selling out the 1919 World Series to Cincinnati. Among these “Black Sox” were three regulars who had batted well over .300 in 1920, Happy Felsch, Joe Jackson (.382), and Buck Weaver. Much has been written over the years about their relative guilt, or lack of such. The statement of Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, however, set forth a standard of baseball which would end their careers in their prime. Issued after the conclusion of their trial on August 2, 1921 (in which they were acquitted), it read, in part: “Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player who throws a ballgame, no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ballgame, no player that sits in conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing a game. are discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it,will ever play professional baseball!”

After Judge Landis’s decision, each of the three played semipro and outlaw baseball for a number of years. Felsch returned to his hometown, Milwaukee, working as a crane operator and laborer, and opened a tavern to support his six children. Jackson played baseball until 1933, continuing a valet business and, later, buying a liquor store. He remained active in the management and administration of several semipro teams and leagues. Weaver repeatedly made appeals to Landis for reinstatement, but all were bluntly denied. He continued to run a drugstore for many years, and later worked the parimutuel windows at a local racetrack.

*****

By far, most of those major league regulars (twenty) who batted .300 in their final seasons continued their careers in the various minor leagues that once dotted the American landscape.

Perry Werden was one of the most feared minor league batters of the 1890s, and played portions of seven seasons in the big leagues. In Minneapolis he hit 45 home runs in 1895—a record that stood throughout all baseball until the 1920 onslaught of Babe Ruth. In 1897 he was drafted by Louisville (then a major league franchise), where he compiled his highest big-time average, leading NL first basemen in putouts and assists as well. The following season, however, he returned to Minneapolis unfortunately breaking his leg and missing the entire 1898 season. Thereafter his power totals were reduced, but he continued to hit for a high average into 1906. He eventually made his home in Minneapolis.

George Sisler always insisted that his real career ended in 1923 when, after batting .420 the season before, he missed the entire season with a severe sinus infection which produced double vision. He returned to play major league ball in 1924-30 until, with his legs “gone,” he was unconditionally released by the Braves. He then batted .303 for Rochester and was released. The following year he dropped out of his player-manager position at Shreveport-Tyler when asked to take a large pay cut. He spent most of the 1930s as a businessman in St. Louis.

Buzz Arlett, like Harry Moore and Irv Waldron, as well as part-time .300 hitters Tex Vache (1925) and Monk Sherlock (1930), enjoyed only one season in the major leagues. He was, however, the greatest switch-hitter in minor league history, averaging .341 and blasting 432 home runs in 19 seasons (the first five largely as a pitcher). His first thirteen seasons were spent with Oakland of the Pacific Coast League. Depending on who ventured the opinion, Arlett was confined to the minors due to his fielding weaknesses, high price, temperament, or bad timing (the PCL President voided Arlett’s 1930 sale to Brooklyn after an altercation with an umpire). After his .313 NL season with the Phillies, who had purchased him for a healthy sum from Oakland, he was traded to minor league Baltimore.

Urban John Hodapp stands as the only ballplayer in this century who closed out his major league career as a regular batting .300—and ended the minor league tour which followed in the same manner.

Born in Cincinnati in 1905, “Johnny” had an uncle who took considerable interest in his baseball development. By the early 1920s, young Hodapp’s abilities stood out in several of the small amateur leagues which dotted the Queen City, and he turned semipro in 1923. Two years later, after a turn in the minors with Indianapolis, he appeared in 37 games with Cleveland. Although he batted only .238, his showing was stronger than that of three-year incumbent third baseman Rube Lutzke, and rapid improvement was expected. Instead, during spring training of 1926, he suffered a broken leg, limiting him to only five at-bats with the Indians that season.

In 1927, however, Hodapp returned to bat .304 in halftime duty. His next season, finally as the regular third baseman, was even better: his line drives produced a .323 mark, complemented by 73 RBis. By that time, Hodapp was reaching his physical prime, a sturdy six-footer at 180 pounds, batting and throwing righthanded.

Unfortunately, in the following years, his knees were a constant source of trouble. Moved to second base in 1929 (his position thereafter), he managed to bat .327, with the benefit of increased pinch-hitting roles. During the offseason, taking special care of himself, he prepared for the 1930 campaign.

Teamed with Earl Averill, Eddie Morgan & Co., Hodapp played in all 154 games, leading the league in hits (225) and doubles (51), driving in 121 runs while batting .354. Though not a smooth fielder, he did pace AL second basemen in putouts. The 1930 season indicated what a healthy John Hodapp could do.

The next campaign, however, saw the return of serious concerns about his knees. Though he managed a .295 mark, both his power at the plate and mobility in the field were noticeably diminished. By 1932, it was clear that ligament damage was involved. Given the surgical care of fifty years ago, Hodapp was warned that an operation could possibly leave him with a stiff knee—so he chose to make the best of his situation. That season marked the close of his career with the Cleveland Indians, and he finished out the torturous year in the White Sox outfield and as a pinch hitter. Chicago let him go after its 49-1 02 season, and Hodapp signed with an AL team which was even more inept, the Boston Red Sox (43-111).

The 1933 Red Sox improved to 63-86. But, most significantly, the beginning of the Tom Yawkey era marked the end of the major league trail for four great hitters: Bob (Fatty) Fothergill, Dale Alexander, Smead Jolley—and Johnny Hodapp. The game second baseman was leading the league at .374 in June but, plagued with continued physical liabilities, declined to a still respectable .312 with 27 doubles. On October 31, with the Sox making rebuilding plans, Hodapp was released.

Not yet 30, and still in love with the game, he did not seriously consider retiring. Instead, he turned to the minor leagues. Hodapp split the 1934 season between Columbus (.344) and Knoxville (.307). This one year back in the minors was enough to convince him he would not be returning to the majors. He considered umpiring but, by this time, his father was waiting for a decision on the business offer which had been open for a decade: Johnny Hodapp returned to Cincinnati as a director in the family funeral home, with his brothers. He passed away in 1979.

In 1945, three American Leaguers batted over .300 in qualifying for the batting title, two of them on the Chicago White Sox who released both—Tony Cuccinello and John Dickshot—in anticipation of the return of the World War II veterans. Cuccinello, in 1941 the manager of the Giants’ Jersey City farm club, had joined the Braves for the 1942 campaign and, during his final stint with the White Sox, led the league in batting (“strictly from memory”) almost until the final day. His outright release came as a complete surprise for, as the UPI noted, “the old Cuccinello was better than the Cuccinello of old.” He remained in the New York area in 1946, playing semipro baseball and turning down other opportunities due to family concerns. He managed the Tampa Smokers in 1947, batting .067 in seven games. Soon after, he began a coaching and scouting career, notably with Al Lopez, which would last for decades.

*****

“One of the great thrills of my life,” Ted Williams once observed, “was when I was 14 and discovered I could hit whatever my friend Wilbur Wiley threw.” Cap Anson would, no doubt, have smiled in agreement, remembering his mastery of the hurlers of another era. A selective survey of those major league regulars batting .300 in their final seasons, however, clearly underlines a fact of baseball life: for some players a strong season at the plate simply isn’t enough.

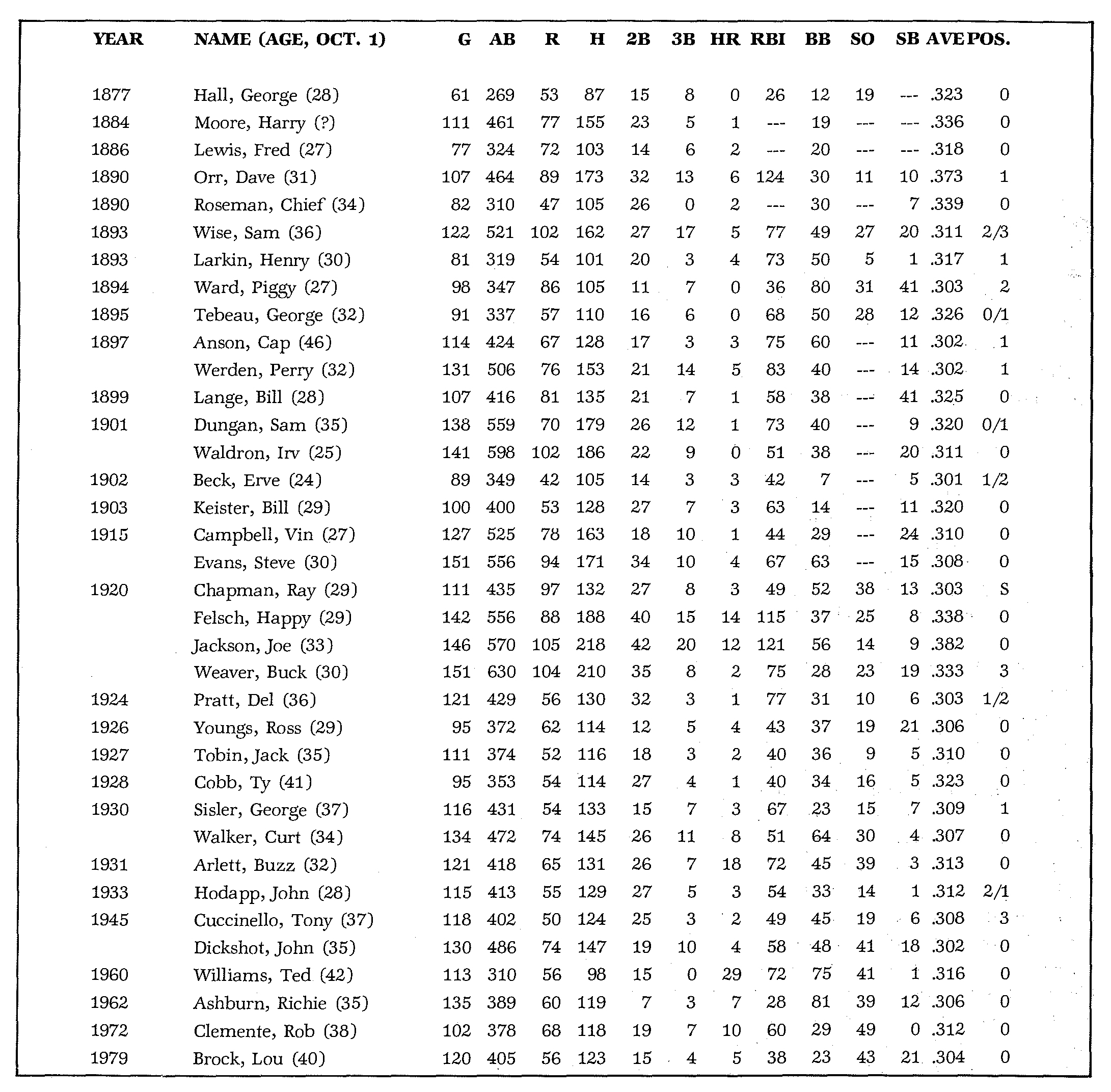

(Click image to enlarge)