A History of the 1939 Baltimore Elite Giants

This article was originally published in The 1939 Baltimore Elite Giants (SABR, 2024), edited by Frederick C. Bush, Thomas Kern, and Bill Nowlin.

By 1939 the Elite Giants had earned the moniker “The well-traveled Elite Giants.” The team’s arrival in Baltimore in the spring of 1938 marked the end of a long search for a dependable fan base and financial stability. Seventeen years earlier, at a January 7, 1921, meeting of team officials in the Elite (pronounced “EE-lite) Pool Room in Nashville, Tennessee, 38-year-old president and owner Thomas T. “Smiling Tom” Wilson had renamed the Nashville Standard Giants, a semipro team he had founded in 1918, the Nashville Elite Giants. The name “Giants” indicated, in the vernacular of the day, that it was a “colored” team.1 Wilson promised Nashville residents the team “will be the fastest Colored club in the south next season.”2

By 1939 the Elite Giants had earned the moniker “The well-traveled Elite Giants.” The team’s arrival in Baltimore in the spring of 1938 marked the end of a long search for a dependable fan base and financial stability. Seventeen years earlier, at a January 7, 1921, meeting of team officials in the Elite (pronounced “EE-lite) Pool Room in Nashville, Tennessee, 38-year-old president and owner Thomas T. “Smiling Tom” Wilson had renamed the Nashville Standard Giants, a semipro team he had founded in 1918, the Nashville Elite Giants. The name “Giants” indicated, in the vernacular of the day, that it was a “colored” team.1 Wilson promised Nashville residents the team “will be the fastest Colored club in the south next season.”2

Nashville and the Negro Southern League

The team was one of 10 teams in the Negro Southern League in 1921. Teams returning from 1920, the league’s first season, were the Birmingham Black Barons, Knoxville Giants, Montgomery Grey Sox, and New Orleans Caulfield Ads. New teams, in addition to the Elites, were the Memphis Red Sox, Mobile Braves, Chattanooga Tigers, Atlanta Black Crackers, Bessemer Alabama Stars, and Gadsden Alabama Giants.3

Opening Day on April 25, 1921, began with a festive occasion that Wilson continued to invoke at opening days in the years to come. The club’s directors led a parade consisting of a brass band and automobiles carrying members of both teams – the Elites and the Memphis Red Sox. A community leader threw out the ceremonial first pitch.4 The highlight of the Elites’ maiden season was a 17-game winning streak in July and August on their way to copping the pennant in the newly organized 1921 version of the NSL, which was considered a “minor league” of the African American leagues. Rube Foster’s recently created Negro National League was the preeminent Black league of the day.

Pitching led the way. Three no-hitters, one by Wild Bill Nesbitt and two by rookie Darltie Cooper, brother of Hall of Fame pitcher Andy Cooper, highlighted the team’s inaugural season. Cooper finished the season with a 14-8 record, while Frenchy Gibson led all Elite moundsmen with a 15-6 record. Full of confidence and bravado after receiving the championship silver cup, Wilson announced, “The Nashville club will play any team anywhere.”5

While it is unknown if any team accepted Wilson’s challenge, the Elites started the 1922 season in fine fettle. They swept five straight games from the Louisville Cardinals, a new addition to the NSL. Wilson expanded a strong pitching staff with the addition of Ralph “Square” Moore from the New Orleans Crescents and two outfielders, Will Holt and George “Jew Baby” Bennett. Wilson named third baseman Felton Leroy Stratton as manager. Stratton could also play any position and wielded a decent bat as was evidenced by his six hits in a doubleheader win over the Birmingham Black Barons. Newly acquired shortstop Hooty Phillips, a baserunner extraordinaire, beat many a catcher’s throw to second and third base.6 By early June, Nashville led the NSL with a 20-15 record.7 By July 30, they led the pack by three games and finished in first place for the first half of the season. However, Wilson’s men did not have a chance to defend their previous season’s championship, since the entire NSL folded in early August due in part to mismanagement and lack of baseball experience on the part of some team owners. The Elites and several other teams continued as independent ballclubs.8

The ensuing three seasons (1923-1925) saw fragmentation again characterizing the NSL. Team owners had decided to split the 1923 season into a first and second half, but the league once again dissolved, this time before the second half began. Several teams went under for financial reasons. Two teams, the Birmingham Black Barons and the Memphis Red Sox, cast their lots with the Negro National League. The Nashville Elite Giants survived by barnstorming through the 1924 and ’25 seasons.

The 1926 season saw another resurrection of the NSL. Wilson’s Nashville Elite Giants joined seven other teams, each of which put up a $500 franchise fee and $70 “for promotional purposes.”9 Always on the lookout for capable players, Wilson dispatched his right-hand man and club secretary, Vernon “Fat Baby” Green, on a tour of several Northern states in early June. Green had been a catcher on the 1921 Elites but found his talent lay more in administration than playing, and he served as Wilson’s aide-de-camp for more than 20 years.10 He returned with four players – pitcher Clarence White, catcher Russell Bailey, outfielder William Mc Neal, and shortstop Joe Cates.11 The new players did little to improve the Giants’ performance, and the team languished in sixth place as the season ended. In two games of note, the renamed Chattanooga White Sox beat the Elites behind the pitching of a 20-year-old rookie named Satchel Paige.12

In 1927 the Elites started on a more promising note. Wilson had again revamped the roster, and only four players remained from the 1926 team. Wilson acquired Joe Hewitt from the Chicago American Giants in the NNL “at great expense” to replace Felton Stratton as manager.13 Stratton remained with the team as a player and returned to the hot corner. Hewitt turned to managing as his 17-year career as a stellar infielder was coming to an end. Wilson acquired several players from other NSL teams, notably pitcher Jim “Cannonball” Willis and catcher Red Charleston. The Nashville Banner predicted that the team would be “strong.”14

The paper’s prediction proved true for the first half of the season, in which the Elites were “generally declared to be the winner” amid conflicting newspaper accounts of games won and lost. Results for the second half of the season were not published. The Elites, however, won a championship that year, capturing the Negro Dixie Series title. Their first-half win entitled the Elites to represent the NSL against the Dallas Black Sox, champions of the Black Texas League. The Elites beat the Texans, 5-4, in the series’ final game before a wildly cheering crowd at Sulphur Dell. The Negro Dixie Series mirrored that of the annual postseason matchup between the champions of the White Southern Association and the Texas League (also White).15

A Move to the Negro National League

Eager to improve his team’s performance and prestige, Wilson attended the1928 annual NNL winter meetings, held as usual in January in Chicago, in hopes of joining the league, which was deemed to be the “major league” of Black baseball. He came away with a promise that the Elites would be considered an associate member of the league and that full membership would be granted should the Memphis Red Sox drop out. Games with associate members did not count in the standings, and associate members could not compete for the pennant. Memphis stayed in the NNL, and Wilson returned to Nashville only to see the NSL disintegrate once again.16 The Elites, as an associate member of the NNL, played independent ball that year, and they continued to do so during the 1929 and ’30 seasons.17

One of the 1930 games, played on May 14 in Nashville’s Wilson Park against the NNL’s Kansas City Monarchs, was notable for two reasons: 1) It drew one of the largest crowds in recent memory, and 2) it was the first night game ever played in Nashville. Floodlights at first and third base and two in the outfield provided the illumination. The Monarchs prevailed, 4-3. Wilson Park, built by Tom Wilson in 1928, had a capacity of 8,000 spectators and afforded the team the ability to schedule games independent of the White minor leagues’ Nashville Vols’ schedule. Games for which the crowd was expected to exceed 8,000 continued to be played at Sulphur Dell.18

The year 1930 also marked Wilson’s first foray to California. The California Winter League accepted his application to field a team he called the Elite Giants. This was not the Nashville Elite Giants but rather a handpicked aggregation of the top “colored” players. They included St. Louis Stars shortstop Willie Wells and first baseman-outfielder Mule Suttles, “The Race Babe Ruth”; pitcher Satchel Paige; outfielder Norman “Turkey” Stearnes from the Detroit Stars; and third baseman Judy Johnson from Pittsburgh’s Homestead Grays – all eventual Hall of Famers. Wilson claimed the Elites “will be the most popular on the Coast.” Whether or not the team was the most popular, it was certainly the best. They won the 1930-31 CWL championship. It would not be their last.19

The Moves Begin

At the same time, the Elites were finally granted full membership in the NNL for the 1931 season. Wilson’s NNL membership, however, was for Cleveland, not Nashville. He moved the Elites franchise to the City by the lake, where the team played as the Cleveland Cubs. Notable Cubs players included Satchel Paige and a 19-year-old rookie infielder named Ray Dandridge, who had quit the floundering Detroit Stars due to that team’s financial difficulties. After a short stint with the Cubs, Dandridge starred in the Negro Leagues for 16 seasons and gained induction into the Hall of Fame in 1987.20

Wilson rarely left Nashville, where he had a number of business interests, so he relied on Vernon Green to oversee all games. One game, however, brought Wilson to Cleveland. In a July game against Louisville, Paige, in a fit of pique, threw a ball at umpire Baby King and cussed him out. King ejected Paige, prompting Cubs manager Joe Hewitt to call the Cubs off the field. Green and Louisville manager Columbus Ewing managed to quell tempers so the game could continue. The incident added fuel to the criticism that Black baseball had descended into a state of rowdyism brought on by a lack of interest on the part of managers and owners. Hearing about the fracas, Wilson arrived in Louisville, where he fined Hewitt and suspended him for five games. The Chicago Defender complimented Wilson’s actions as “the right step in the direction of restoring the game to its former high plane.”21

While no standings were published, incomplete records show the Cubs were credited with a 24-22 record for the portion of the season during which the team was in business. The Great Depression was in full swing and practically all of Black baseball felt its sting. The NNL disbanded, the Cubs folded, Paige signed with the Pittsburgh Crawfords, and Wilson took the remaining Elites back to Nashville for play in the NSL for the rest of the 1931 season.22

While many of the Elites’ best players had migrated to Cleveland, fortune smiled on those left behind and perhaps others who made up the ’31 Nashville Elite Giants based in Nashville. Wilson now presided over two teams; one in the NNL II and one in the NSL. The two teams faced each other at least once in late April for a doubleheader. The Cubs easily took both games, 7-1 and 5-0.23 By the end of June, the Nashville team led the NSL, and its resurgence was highlighted by an 11-game winning streak. By July, however, its lead had been cut to one game over the once-again-renamed Chattanooga Lookouts. In the end, the Nashville Elites squeaked by the Memphis Red Sox to take the first-half pennant by a mere 3 percentage points.24 The Elites went on to win the second-half flag as well, thus earning the right to play the Monroe Monarchs, champions of the Texas-Louisiana League. The Elite Giants lost the series in seven games. The Chicago Defender called the series “one of the most heated battles that has ever been played in the South.”25

A New Negro Southern League

While the Elite Giants were tearing up the CWL out West, a new Negro Southern League consisting of six teams was organized, with Wilson’s Nashville Elite Giants among the member franchises. Wilson was elected league treasurer. Reuben B. Jackson, his friend, physician, fellow frequent NSL officer, and Nashville resident, was elected vice president. To contain costs, the NSL limited the number of teams to six, with each team carrying 13 players (including the manager).26

As the Depression continued to take its toll, teams that once belonged to the defunct Negro National League either folded or sought new affiliations. Wilson consolidated the Elite Giants into one team in the NSL for the 1932 season. That season the powerhouse Chicago American Giants joined the NSL. Chicago and Nashville finished the season as the top two NSL teams and faced off in the Dixie Series, which was broadcast over the radio by both NBC and CBS. The American Giants, behind the likes of future Hall of Famers Willie Foster (half-brother of Rube Foster) and Turkey Stearnes, a Nashville native best known for his play with the Detroit Stars, won the seventh and deciding game at Wilson Park, 3-2. Shortly thereafter, Wilson took an all-star Black team to the West Coast for another championship season in the CWL.27

While the Elite Giants continued their mastery of the CWL, six of Black baseball’s most prominent moguls met in January 1933 in Chicago to reconstitute the Negro National League, known initially as The National Association of Baseball Clubs but later renamed the Negro National League II (NNL2). The Elite Giants, based in Nashville at the time, finally achieved full membership.28

In their first season as full NNL2 members, Wilson’s Nashville nine finished third in the first-half standings but picked up their play and claimed the second-half title. This qualified the Elite Giants to face the Crescent Stars of New Orleans in the Negro Dixie Series. Considerable prestige was at stake as the winner of the series was to be crowned the best team in the South. The honor went to the Crescents but not without controversy sparked by faulty newspaper reporting.

New Orleans won the first three games before an appreciative home crowd of over 11,000 spectators who cheered Nashville’s star pitcher Cannonball Willis’s offerings and those of his relievers “being swatted to all corners of the lot.”29 The teams then traveled to Nashville for the final four games. A Chicago Defender article of September 23, 1933, credited the Elites with winning both ends of the opening doubleheader, thereby narrowing the Crescents’ lead to 3-2. H.D. English, secretary of the Stars club, took issue with the account. He accused the sportswriter for the Elites of being asleep during the doubleheader and asserted that the Crescents had won the double bill, 2-1 and 7-4, making them victorious in the series, five games to two. “I am wondering,” English continued, “just what the Nashville fans will say as they sat there and saw the Giants lose.”30

As the Dixie Series was underway, Wilson once again assembled a team of Negro League stars to take to California. His latest squad, now named the Royal Elite Giants, once more came out on top of the CWL, giving Wilson’s teams four pennants in four seasons. The pitching of Satchel Paige and Cannonball Willis foiled the bats of many opponents. Willis had been a mainstay of the Nashville team from 1927 to 1934 and was one of the few Nashville Elites to travel west in the winters. The bats of sluggers Mule Suttles, Turkey Stearnes, and Wild Bill Wright complemented the slick fielding of shortstop Willie Wells and Elite infielders Sammy T. Hughes at second base and Felton Snow at third as the Royal Elite Giants rolled to another CWL pennant to the tune of a 34-5 record.31

Elites Back in the Negro National League

As the Depression continued, owners expressed more interest in minimizing travel costs by placing teams in Eastern cities, which were closer to one another than those in the Midwest and South. In January 1934, the NNL2 owners met in Philadelphia rather than Chicago and emerged with a few new member teams that gave the league a decidedly Eastern flavor. The league comprised the Philadelphia Stars, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Chicago American Giants, Newark Dodgers (soon to become the Newark Eagles), Nashville Elite Giants, Baltimore Black Sox, Philadelphia Bacharach Giants, and Cleveland Red Sox. The Elite Giants, heavy preseason favorites “to be among the big threats,” were strengthened by the addition of pitcher Walter “Steel Arm” Davis and manager Candy Jim Taylor, recognized as one of the game’s smartest managers. The Elites ended up being less than the big threat envisioned by Wilson to claim the NNL2 pennant; Seamheads shows the team finishing in fifth place.32

Yet another change was in store for the Elites in 1935. No longer the Nashville Elite Giants, they were slated to become the Detroit Elite Giants, a location that would put them closer to other teams in the league. A White Detroit businessman, John Roesing, who was assumed to be the owner of a lease for Roesing Stadium in the nearby village of Hamtramck, welcomed the team and promised to make all necessary repairs to bring the park up to date. “Well, I’m glad that’s over,” a relieved Wilson sighed once the negotiations had concluded. The trouble was that Roesing had unknowingly lost his lease on the park by nonpayment of taxes. By an action of the Hamtramck City Council, the lease was now in the hands of the Detroit Lumber Company and the city of Hamtramck, and a full schedule of semipro games in the ballpark for a local White team already had been arranged. Upon hearing the news, just a week before Opening Day, a not-so-relieved Wilson quickly relocated the team to Columbus, Ohio, in time for Opening Day against the New York Cubans on May 16, 1935. The Columbus Elite Giants finished third in the NNL2 standings, just .003 percentage point ahead of the Philadelphia Stars.33

Dissatisfied with Columbus, Wilson again sought greener pastures. The nation’s capital caught his eye. Washington was only 40 miles from Baltimore, and both cities had large and growing Black populations. In an effort to tap both markets, Wilson decided that the now Washington Elite Giants would play their day games in DC and split their night games between the two cities. The team boasted an impressive roster.34 Jim “Shifty” West at first base had proved to be a consistent .300-plus hitter the last two seasons and delighted fans with his fancy glove work. Sammy T. Hughes was considered the league’s premier second baseman and was a solid hitter with speed on the bases. Team captain and sometimes manager Felton “Skipper” Snow, who held down the hot corner, owned a rifle of an arm, respectable batting averages, and a knack for stealing bases. Snow managed the team through most of the 1940s.

Bowlegged Leroy Morney, who had been with the Elites for two seasons, was seen “as a master shortstop” and completed the infield. The outfield consisted of Wild Bill Wright, who hit the long ball from both sides of the plate, had a strong if not always accurate arm, and was considered the fastest Negro League player; Zollie Wright, who was no relation to Wild Bill, usually batted cleanup and manned right field; and Homer “Goose” Curry, an adequate outfielder who played four season for the Elites, started in left. The Elites featured a strong pitching rotation of Schoolboy Bob Griffith, Andy Porter, Jim Willis, and Tom Glover, a hard-throwing sophomore.

Of particular note was the addition of Biz Mackey, a 2006 inductee into the Hall of Fame, to the lineup at the catcher’s spot. The “old man” of the team at age 38, Mackey, acquired in a trade with the Philadelphia Stars, kept runners hugging their bases, hit with power, and would mentor

a 15-year-old rookie catcher named Roy Campanella when he joined the team in 1937. Campanella, a native of Philadelphia, was the only player on the ’37 team born north of the Mason-Dixon Line. The rookie learned well but didn’t find the mentoring easy. “Biz,” he said, “didn’t want me to do just one or two things good. He wanted me to do everything good. … There were times when Biz made me cry with his constant dogging. But nobody ever had a better teacher.”35

With this lineup, manager Candy Jim Taylor, who had been an exceptional third baseman before embarking on a successful managerial career, including the past two seasons with the Elite Giants, predicted that the team “will be a first division club.”36

Taylor’s prediction proved true for the 1936 season’s first half but not until a decisive game with the Philadelphia Stars, postponed in June, was finally played in September. The Giants won and were belatedly recognized as the league’s first-half winner. They fared less well in the second half by losing the title to the Pittsburgh Crawfords.37 Often the winners of the first half and second half faced off in a NNL2 championship series, but for unknown reasons no such series was played this season. William Augustus “Gus” Greenlee, a Pittsburgh tavern owner and Black community leader, in his capacity as NNL president and, not incidentally, owner of the Crawfords, ruled that the title belonged to the Craws as they had best record for the entire season; a .593 winning percentage against .460 for the second-place Elites.38

The bus that carried the Elites south for spring training in March of 1937 held essentially the same roster as the year before with two notable additions. 20-year-old Jimmy Direaux, a right-handed pitcher and a Los Angeles native, came to Wilson’s attention by striking out 108 batters in a six-game stretch for the semipro Arizona Broncos, an accomplishment featured in Ripley’s Believe It or Not. He ended up spending two unremarkable seasons with the Elites before jumping to the Mexican League. Henry “Kimmie” Kimbro, a 25-year-old outfielder, was the second acquisition. An all-around exceptional player, he remained with the Elites for 11 seasons, an unusually long tenure with a single team in the Negro Leagues. Biz Mackey replaced Taylor as manager while Campanella, still in high school, played occasionally. Douglass O. Smith, a booking agent with the power to arrange Negro League games at certain ballparks in return for a fee, put a dent in Baltimore’s segregation policies by securing the city’s best stadium, Oriole Park, for Elites’ night games. The ballpark had been closed to “colored” teams for years.39

The 1937 Washington Elites came out of the gate in fine fashion. By the end of May they were in first place in the six-team league. By the end of July, they maintained their lead by downing the New York Black Yankees in a doubleheader. But it was downhill for the rest of the season. Wilson’s nine fell to fifth place at season’s end with a 23-36-3 record, thereby dashing early-season hopes for a pennant.40

Baltimore

Not only was Washington’s record a disappointment, but its finances were as well. Wilson once again searched for a city that would adequately support the Elites. He decided on Baltimore. “Last year,” he lamented at the 1938 annual owners’ winter meeting, “we lost money with the club operating from Washington. I sincerely feel Baltimore is far superior to Washington as a baseball town.” But there was a hitch. Wilson wanted to play in Oriole Park, home park of the Independent League Baltimore Orioles, but to do so he’d have to again go through Smith, which would cut into the team’s finances.41 Wilson’s reluctance to work with Smith, together with the objections that White citizens voiced to Oriole Park officials about the “noise and fanfare” generated by night games the previous season, resulted in Bugle Field becoming the Elites’ home park for the 1938 season.42

Wilson’s optimism about Baltimore was buoyed by the efforts of Richard Powell who had many contacts in the city. He talked up the Elites to Black leaders and community groups. Powell gained the backing of Baltimore’s chapter of the Frontiers Club of America, composed of leading businessmen, which supported minority group leaders striving to ameliorate racial, social, and civic issues. He also gained the support of Leon Hardwick, the Baltimore Afro-American’s sports editor. Hardwick promised to run frequent articles about the team, many of which Powell wrote on his second-hand typewriter. Powell also arranged for some players to stay in private homes, including his own, where they could enjoy home-cooked meals. Others stayed at the Clark Boarding House and ate at segregated restaurants. His biggest financial contribution was to lease Bugle Field for the Elites from its owner, the Gallagher Realty Company, saving Wilson the usual 10 to 15 percent fee charged by booking agents.43

Baseball was the main attraction at Bugle Field, but it was not the only one. The ballpark was a haven where people could relax and have a good time without the stress generated by Baltimore’s culture of segregation and discrimination. Frederick Lonesome, a frequent spectator, recalled, “You didn’t have to have a lot of money to enjoy yourself, and you didn’t have to be afraid.” Gambling was enjoyed by many. Lonesome recalled “seeing coins and dollar bills change hands as people bet on what the batter would do, like make a hit or get an out.” Home-brewed whiskey, either gin or rye, sold for $3.00 a pint; a beer cost 20 cents. Candy, hot dogs, peanuts, and ice cream were plentiful. Many dressed to the nines and brought picnic baskets.44

The now Baltimore Elite Giants, the youngest team in the league the previous year, started 5-6 but began to find their footing. The Pittsburgh Courier lauded their “speedy pace” in the second half by trouncing the Homestead Grays 8-4 in a late July game,45 They finished in fifth place, but a writer for the Courier hailed the soon to be Baltimore Elite Giants as pennant contenders for the coming 1938 season.46

Such hopes were dashed early. By the second week of June 1938, the Elites found themselves in fourth place in the NNL2 with a 5-6 record. By the end of the first half, on July 4, the team had slipped a notch to fifth place. Second-half standings were muddled because of inconsistent scorekeeping and some teams not reporting the outcomes of their games. Greenlee and Cum Posey, owners of the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays respectively, filled the void by listing the second-half order of finish as follows: the Grays in first place followed by the Philadelphia Stars, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Baltimore Elite Giants, Newark Eagles, and New York Black Yankees. How the two men arrived at their findings is not known, but they gave the league championship to the Grays, who had won the first half with a 26-6 record.47 In spite of the Elites’ disappointing record, Wilson saw enough bright spots to keep the team in Baltimore. For one thing, the box office had been good to him. In addition to that, Hughes, Wright, and Mackey had been elected to the East squad for the East-West All-Star Game, held at Comiskey Park on August 21.

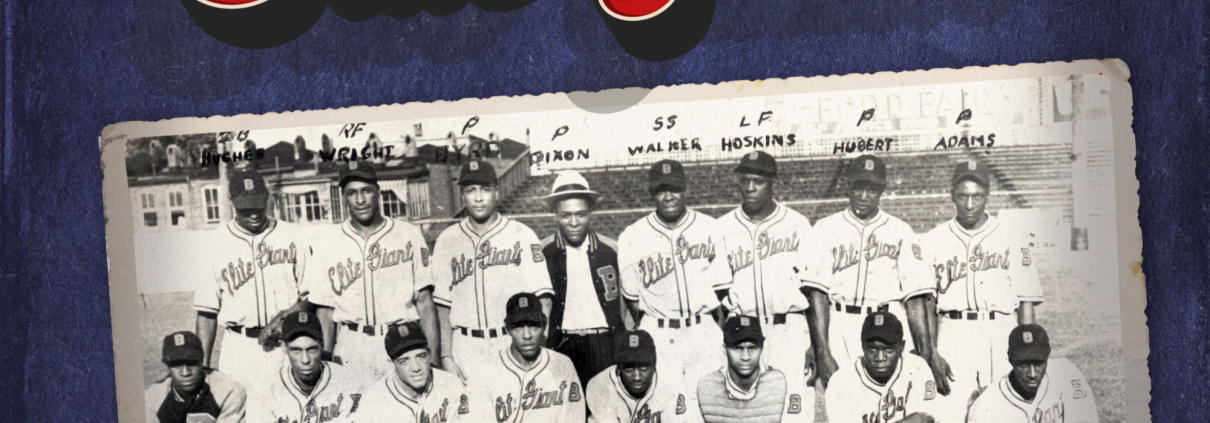

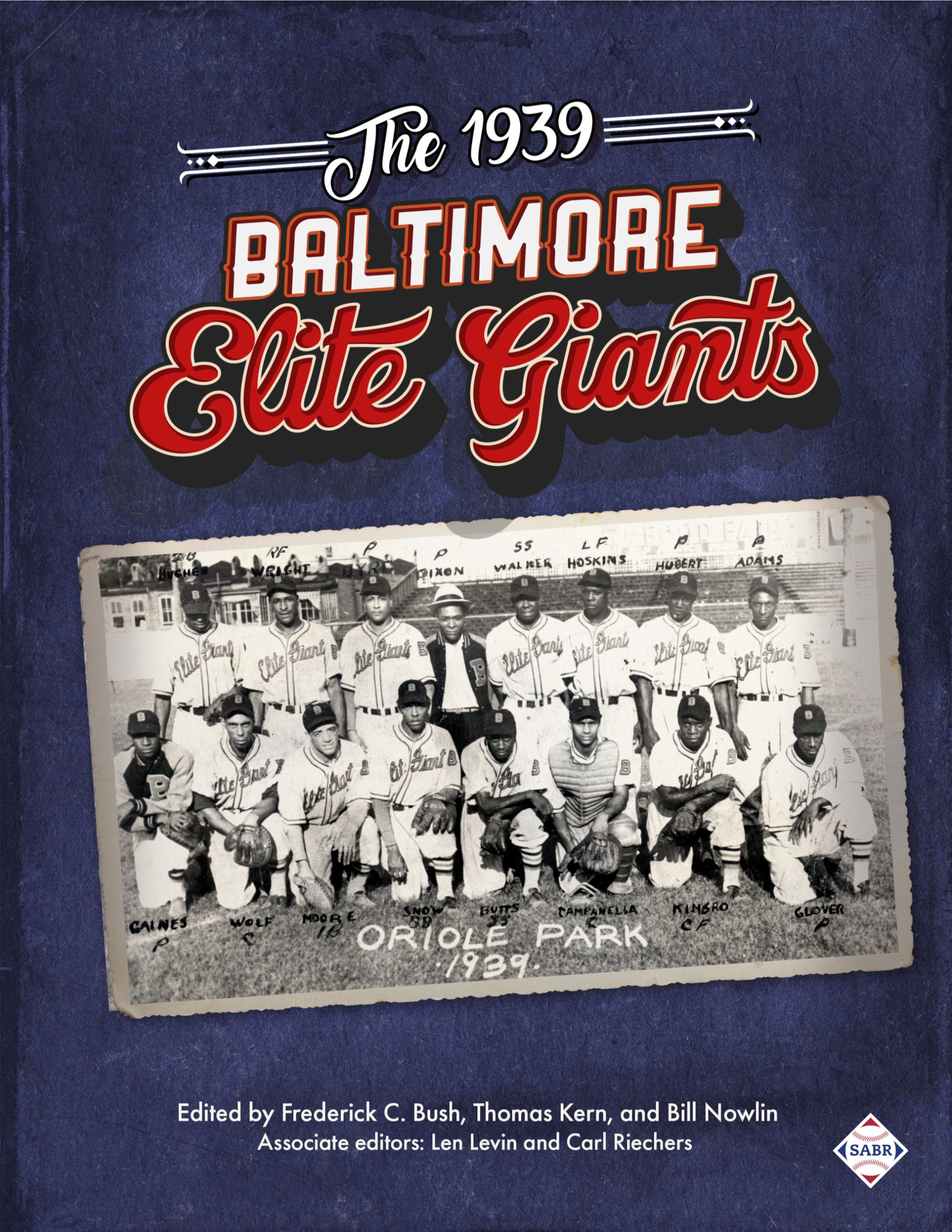

The Elites fared better in 1939 despite the fact that three starting pitchers, Andy Porter, Schoolboy Griffith, and Jimmy Direaux, had cast their lots with the Mexican League before spring training had started in Nashville. A bit of good news was that booking agents Ed Gottlieb and Smith persuaded the owners of Oriole Park, with 2,000 more seats than Bugle Field, to allow the Giants to play several doubleheaders there. Wilson paid their fee, banking on the possibility of more spectators than Bugle Field could accommodate. The first game at Oriole Park was an Opening Day doubleheader on Sunday, May 19, against the Grays. The Elites took a double drubbing, 7-1 and 11-0. Wilson’s roster shook off their inglorious start and managed to place third in the first half of the season while the Grays again easily took first place.48

As the second half got underway, a second competition – the Jacob Ruppert Memorial Cup Tournament – was introduced in late June. In a rare acknowledgement of the Negro leagues by a major-league organization, Ed Barrow, former general manager and recently appointed president of the New York Yankees, selected five NNL2 four-team doubleheaders to be played in Yankee Stadium as Ruppert Cup games. The winner of the most games would be awarded a trophy and $500. The games honored Col. Jacob Ruppert, the Yankees’ owner and president from 1915 until his death on January 13, 1939, a four-term congressman, and the owner of Ruppert Brewery. Ruppert had opened Yankee Stadium to Negro League teams on July 5,1930, when the New York Lincoln Giants and the Baltimore Black Sox played a doubleheader. As Barrow introduced the Ruppert Cup, he said, “Negro baseball can build its own structure right alongside the majors. Given sufficient opportunity to show their ability, the colored stars will undoubtedly attract thousands of fans and supporters who will help them in their fight to reach the pinnacle of organized baseball.”49

Whether the prospect of winning the Ruppert Cup built a fire under the Elites is not known, but their second-half performance showed marked improvement. They took three straight from the Philadelphia Stars to start the second half. Wilson again changed personnel as he acquired five players from the Atlanta Black Crackers, a move the Chicago Defender described as “the biggest switch in players to be heralded in many seasons.” To make room for the new men, Wilson sold Mackey to the Newark Eagles and West to the Philadelphia Stars. The new Elites were James “Red” Moore, a fancy fielding and good hitting first baseman; two pitchers, Ed Dixon and Felix Evans; catcher Oscar Boone, who could back up Campanella now that he was the starting backstop; and the pick of the litter, shortstop Tommy “Pee Wee” Butts, who stayed with the Elites until 1951 (save for jumping to the Mexican League for the 1943 season).50 Lennie Pearson, the longtime first baseman of the Newark Eagles, said of him, “Butts was a tremendous shortstop and pesky hitter. He could go behind second better than any man I ever saw.” Pearson said that Butts’s “love of life” kept him out of the majors: “[H]e loved life, and when I say he loved life, I mean he loved life, especially women. After a game, Butts had a tendency to go off on the town, while Gilliam would stay around and listen to the old-timers talk and soak up that knowledge of baseball.”51

The “switch” in personnel helped. The Elites played above .500 ball for the rest of the season to edge the Grays for the second-half NNL2 championship. This year, instead of pairing the winners of the first and second halves for the NNL2 championship, the owners decided on two five-game series to determine which teams would contend for the title. Perhaps the additional revenue that would come from the extra games influenced their decision. Based on total wins for the season, the first-place Homestead Grays were paired against the fourth-place Philadelphia Stars, while the second-place Newark Eagles took on the third-place Elites. The Grays and Elites each won their series to advance to the five-game championship series. Campanella provided the best performance by a hitter in a single game. In Game Four of the championship series, played at Philadelphia’s Parkside Field, Campanella, a Philly native, thrilled the home crowd by leading his mates to 10-5 win with a home run, a double, and two singles.52 The final and deciding game was scheduled for September 24 in Yankee Stadium.

Two Championships and Controversy

Not only would the NNL2 championship be up for grabs on the 24th, but the winner of that game would also claim the Ruppert Cup trophy. Nearly 10,000 spectators saw southpaw Elite pitcher Jonas “Lefty” Gaines shut out the power-laden Grays for seven innings before loading the bases in the eighth with consecutive two-out walks to Grays power hitters Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, and Vic Harris. Gaines gave way to Bubber Hubert, a journeyman right-hander, who retired Grays pitcher Thomas “Big Train” Parker on a popout to protect the Elites’ 2-0 lead. Hubert held the Grays scoreless in the ninth inning.

The Giants had scored both of their runs in the seventh. Bill Hoskins, an outfielder in his second year with the Elites, drove in Wild Bill Wright, who had doubled, with a line-drive single to left field. Campanella soon followed with a single through the box that brought Hoskins, known for his speed on the bases, across the plate for the team’s second tally.53

Gaines had shut down some of the league’s leading hitters. In a list published by Cum Posey at the end of the 1939 season, five of the top 16 batters were Grays. Josh Gibson finished the season banging the ball at a .402 clip, while Sam Bankhead hit .378, Buck Leonard batted .363, Ray Brown finished at .316, and Henry Spearman hit .315. The Elites’ Bill Wright ranked 10th with a .365 average. Amid postgame speeches by several dignitaries, Tom Wilson, with a broad smile across his face, celebrated winning the NNL2 championship and hoisted the Ruppert Cup trophy for all to see.54

The press had no question about who the champions were. “Climaxing an uphill campaign in a blaze of glory, the … Giants won the Negro National League baseball championship and the Jacob Ruppert Trophy,” wrote the Baltimore Afro-American in a September 30, 1939, article. A July 6, 1940, Chicago Defender article referred to the Elites as “champions of 1939.”

The Grays had no problem with the Elites winning the Ruppert Cup, but they did hotly contest the Elites winning the NNL2 championship. Buck Leonard spoke for many when he claimed the Grays should wear the crown because they had won the most games during the season.55 In later years, Grays ownership still seemed unsure about how to present their team’s 1939 season: The team’s stationery for 1947 did not include 1939 as one of their many championship years, but their envelopes for 1949 did.56 Playoff results show that in 1939 the itinerant Elite Giants had two championships to savor.

BOB LUKE took up writing baseball books after a 40-year career in human resource development. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Maryland. His most recent book is Pete Hill: Baseball’s First Black Superstar, published by McFarland. Others include The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues (Potomac Books), The Baltimore Elite Giants: Sport and Society in the Age of Negro League Baseball (John Hopkins University), Integrating the Baltimore Orioles and Race in Baltimore (McFarland), and Willie Wells: “El Diablo” of the Negro Leagues (University of Texas). He lives in Garrett Park, Maryland, with his wife, Judy.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author is thankful for interviews with Frederick Lonesome, Barbara Powell Golden, and Gary Ashwill, and for access to the Art Carter Papers, Box 170-16, Folder 1, Manuscript Division, at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington, DC.

Notes

1 An exception was the New York Giants, which were founded in 1883 and renamed from the Gothams to the Giants in 1885.

2 “Organize Nashville Elite Giants,” Chicago Defender, January 8, 1921. Thomas Aiello, “The Southern Against the South: The Chicago Conspiracy in the 1932 Negro Southern Baseball League,” Journal of Illinois State Historical Society, 1989, Vol. 102, No. 1, Spring, 2009, 10.

3 “Organize Nashville Elite Giants,” Chicago Defender, January 8, 1921.

4 William J. Plott, The Negro Southern League: A Baseball History, 1920-1951 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2015), 25.

5 Richard Schweid, “Club Built Against All odds,” Nashville Tennessean, September 2, 1987; “Elite Giants Win Seventeen Straight,” Nashville Banner, August 15, 1921; “Elite Giants Win Southern Championship,” Chicago Defender, October 1, 1921; www.negrosouthernleagueMuseumresearchcenter.org. Accessed March 21, 2023; James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of Negro Baseball Leagues, (New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, 1994), 192.

6 Plott, 25, 36.

7 “The Southern League,” Chicago Defender, June 3, 1922.

8 Plott, 41; Riley, 247.

9 Plott, 49.

10 Riley, 336.

11 “Elite Giants Obtain Four New Players” Nashville Banner, June 9, 1926.

12 “White Sox Outfit at Top Negro Loop,” Chattanooga Daily Times, July 7, 1926; “Elite Giants Defeated by Chattanooga,” Nashville Banner, September 6, 1926.

13 “Elite Giants to Be Strong This Season,” Nashville Banner, April 8, 1927.

14 “Elite Giants to be Strong This Season”; Riley, 166.

15 Plott, 74-75; Riley, 379; “Elites Capture Negro Dixie Title,” Nashville Banner, September 12, 1927.

16 Plott, 76.

17 “Elites Opener Is May 4 With Black Barons,” Chicago Defender, April 12, 1929; Plott, 76-80. Gary Ashwill email to author.

18 “Large Crowd Sees First Night Game,” Nashville Banner, May 15, 1930.

19 “Tom Wilson to Enter Strong Club in Coast Winter League,” Chicago Defender, September 13, 1930; James

Newton, “Nashville Elites Win Coast Baseball Flag,” Chicago Defender, March 7, 1931.

20 https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=dandr01ray, accessed May 9, 2023; Riley, 209; Bill Gibson, “Hear Me Talkin’ to You,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 9, 1933.

21 Seamheads.com – Cleveland Cubs 1931; “Thomas Wilson, Owner of Cleveland Cubs, Fines and Suspends Mgr. Joe Hewitt,” Chicago Defender, August 1, 1931.

22 Riley, 179.

23 “Elite Giants Drop 2 Games to Cleveland,” Chicago Defender, April 25, 1931.

24 “Around the Diamond,” Chicago Defender, June 13, 1931; “Elites Lead Dixie League,” Pittsburgh

Courier, July 18, 1931.

25 “Monroe Holds Record for Ball Titles,” Chicago Defender, August 29, 1931; “The Southern League Meets

January 23rd,” Chicago Defender, January 16, 1932.

26 “Negro Southern League Organized,” Nashville Banner, March 15, 1931; Aiello, 12.

27 R.R. Jackson, “Giants, Elites Prep for Dixie Title Series,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 27, 1932; Luther Carmichael, “Chicago Giants Swamp Nashville in Dixie Championship Game,” Atlanta Daily World, September 23, 1932; “Chicago Drubs Elite Giants,” Nashville Banner, October 3, 1932.

28 Al Monroe, “Six Clubs in New League,” Chicago Defender, January 14, 1933.

29 “New Orleans Leads Title Series,” Chicago Defender, September 16, 1933.

30 “Nashville Wins 2, Cops Third Place,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 15, 1933; “Nashville Giants in Negro Dixie Series,” Nashville Banner, September 9, 1933; “Dispute Halts Southern Play-Off,” Chicago Defender, September 23, 1933; H.D. English, “Here’s More About Southern Playoff,” Chicago Defender, September 30, 1933. English simply said the unsigned article the Defender had run on September 23 was incorrect, and that all those present at the game saw the second game played to its conclusion, editorializing further that “[a]rticles going to papers that have tried to help baseball, such as The Chicago Defender, should be exact and correct.”

31 Riley, 865; James Newton, “Nashville 9 Enters West Coast League,” Chicago Defender, September 23, 1933; James Newton, “Nashville Again Winner on Coast,” Chicago Defender, February 10, 1934; Jim Taylor, “Elite Giants Victor in Winter Loop Race,” Chicago Defender, February 16, 1935.

32 “League Season to Open Here May 12,” Chicago Defender, May 17, 1934; “Baseball Men Meet in Philly,” Baltimore Afro-American, February 10, 1934; “Elite Giants Have Roesink Stadium for Detroit Park,” Baltimore Afro-American, March 25, 1935. For final standings, see https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1934&lgID=NN2&tab=standings.

33 “Elite Giants Have Roesink Stadium”; “Detroit Has Team, But No Place to Play,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 11, 1935; Dan Burley, “The Sports Round-Up, “Philadelphia Tribune, May 16, 1935; John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 316. The final standings are per Seamheads.com as of August 2023.

34 “Lewis Wins From Ed Simms,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 14, 1936.

35 Roy Campanella, It’s Good to Be Alive (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1959), 58-59 as cited in Luke, 34.

36 Candy Jim Taylor, “Nashville Elites Play as Washington’s Home Team,” Chicago Defender, April 18, 1936.

37 Seamheads has Pittsburgh as first-half champions and the Elites as second-half champs.

38 Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 26, 1936; “Nashville Seeks Title in Belated Ball Finale,” Chicago Defender, May 1, 1937; Riley, 764-765, 628-629.

39 “Tom Wilson Signs Young Pitching Star,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 27, 1937; “Elites to Use Oriole Park,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 10, 1937; Riley, 462-463.

40 https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/team.php?yearID=1937&teamID=WEG&LGOrd=1, accessed May 16, 2023. “Washington Sweeps Yank Series: Leads Loop,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 24, 1937; “Standings,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 29, 1937.

41 “May Transfer Elite Giants From Washington to Balto,” Baltimore Afro-American, February 5, 1938.

42 “Baltimore Elites Down to Work,” Baltimore Afro-American, April2, 1938.

43 “Vernon Green Succumbs to Heart Attack in Baltimore,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 4, 1949; Riley, 639; Barbara Powell Golden (daughter of Richard Powell) interview, April 27, 2006 as cited in Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants: Sport and Society in the Age of Negro League Baseball (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 160.

44 Interview with Frederick Lonesome, October 10, 2006. As cited in Luke, 30.

[45 “Washington Wins from Grays: Keeps League Lead,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 31, 1937.

[46 “Baltimore Elites to Be Real Pennant Contenders,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 2, 1938. Final season standings are as reported by Seamheads in 2023. “Posey’s Points,” September 26, 1936, and “Nashville Seeks Title in Belated Ball Finale,” May 1, 1937, both cite the Elites winning the first half and the Crawfords the second.

47 Gus Greenlee and Cum Posey, “NNL Turns in Report,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 10, 1938, 23 as cited in Luke, 41.

48 “Homestead Grays Hand Double Beating to Baltimore,” Chicago Defender, May 20, 1919, as cited in Luke, 41-47.

49 https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/ruppert-jacob, Accessed May 27, 2023. “Ed Barrow, President of N.Y. Yankees, Donates Trophy to Negro Nat’l League,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 3, 1939.

50 “Five Atlanta Players Signed by Baltimore,” Chicago Defender, July 22, 1939; Riley, 139. Neither Dixon nor Evans appears on the roster as presented by Seamheads.

51 Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues (New York: Dodd Mead & Co., 1975), 328.

52 https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1939/B09230HOM1939.htm.

53 “Elite Giants Win National League Championship,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 30, 1939; Riley, 394.

54 “Baltimore Whips Homestead Grays for Title,” Chicago Defender, September 30, 1939. “Elite Giants Win National League Championship, Baltimore Afro-American, September 30, 1939; “Wright Gains NNL Batting Crown,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 30, 1939; Riley, 299, 398, 603.

55 Buck Leonard and James A. Riley, Buck Leonard: The Black Lou Gehrig (New York: Carroll Publishers, 1995), 112, as cited in Luke, 51.

56 Art Carter Papers, Box 170-16, Folder 1, Manuscript Division, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington, DC, as cited in Luke, 50.