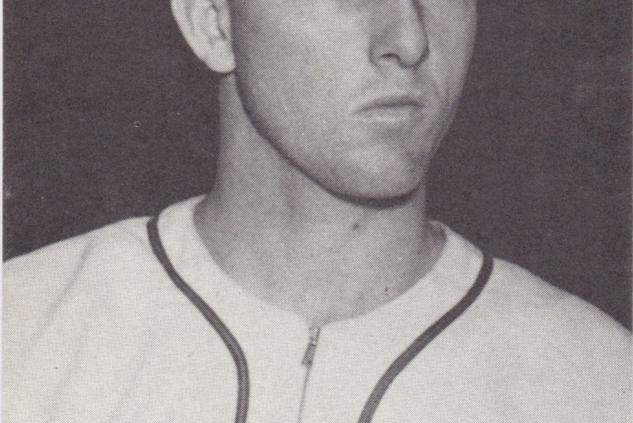

Bill Voiselle

He was a 21-game winner as a rookie in 1944 and four years later started the deciding game of the World Series, but these feats are not what Bill Voiselle is remembered for today. The right-handed pitcher compiled more than 160 victories in a long career split between the major and minor leagues, but it’s the number 96 that remains his claim to fame. This is what Voiselle wore on the back of his Boston Braves uniform, a tribute to the tiny town of Ninety-Six, South Carolina where he was raised and spent most of his life.

He was a 21-game winner as a rookie in 1944 and four years later started the deciding game of the World Series, but these feats are not what Bill Voiselle is remembered for today. The right-handed pitcher compiled more than 160 victories in a long career split between the major and minor leagues, but it’s the number 96 that remains his claim to fame. This is what Voiselle wore on the back of his Boston Braves uniform, a tribute to the tiny town of Ninety-Six, South Carolina where he was raised and spent most of his life.

Until pitchers Mitch Williams and Turk Wendell both donned “99” late in the 20th century, Voiselle’s was the highest number in major league history. Also known as “Big Bill,” the 6-foot-4, 200-pound hurler was dubbed “Ol’ Ninety-Six” in his Boston days, and the nickname stuck for nearly half a century. Even now, years after his January 31, 2005 death, mentions of Bill’s decorated digit routinely pop up in baseball books and trivia games. Making this oddity Voiselle’s sole legacy, however, is not being fair to the man. In addition to pitching professionally for two decades, he was immensely popular with teammates and fans and was a beloved member of his community. And while even casual sports fans of this era have heard the refrain of “Spahn and Sain and Pray for Rain” in reference to a (perceived) thin 1948 Boston rotation, those who actually remember the ’48 season also know the truth: Voiselle — along with fellow starter Vern Bickford — was far more than an afterthought for most of that year.

Born William Symmes Voiselle in Greenwood, S.C., on January 29, 1919, Bill was one of four baseball-playing brothers who as teenagers worked in the local cotton mill when not on the diamond or in class. The story goes that on Sundays, when baseball was forbidden in town, he’d sneak down near the banks of a local river with friends to get in a few innings. Later he starred for a high school team that beat college squads in exhibition games, prompting Red Sox farm club director (and future umpire) Billy Evans to sign the youngster and send him to Moultrie of the George-Florida League in 1938.

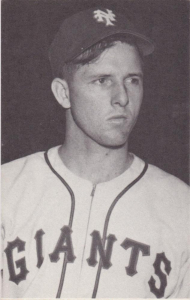

Four years and six teams later, Voiselle was scouted by Giants Hall of Famer Bill Terry while with Oklahoma City of the Texas State League, and purchased by New York’s National League club in August 1942. Although just 7-10 for seventh-place Oklahoma at the time, and primarily a fastball pitcher, the 23-year-old impressed Terry with his exceptional change of pace. His enviable draft status was also a plus. Declared 4F due to a hearing loss, he was ineligible for the military and World War II service.

Voiselle was brought up to the Giants late that season, and made his major league debut against the Cubs on September 1, 1942 — throwing a scoreless inning of one-hit, one-walk relief in a 10-5 loss at Wrigley Field. Player-manager Mel Ott gave Bill his first start on the 25th against the Phillies, and the newcomer performed well: allowing three runs (just two earned) in eight five-hit innings of a 3-2 defeat.

After some more minor-league seasoning at Triple A Jersey City in 1943, where he went 10-21 despite a fine 3.18 ERA, Voiselle was brought back up to pitching-thin New York at the tail-end of that year’s campaign. As recounted by author Frank Graham in his book, the New York Giants, Terry looked at the big right-hander’s lofty loss total and asked Jersey City manager Gabby Hartnett, “What’s happened to Voiselle? I thought he was the best pitcher in the league. But he lost twenty-one games, and won only ten.” Hartnett’s reply? “With that ball club, it’s a wonder he didn’t lose them all. He’s ready, Bill.”

Gabby was right. Voiselle got a start on September 14, and again accorded himself admirably (five innings, five hits, two runs) in a game called off at 4-4 due to inclement weather. The Giants were mired in eighth place, so he also drew starting assignments at Cincinnati and Pittsburgh during the season’s waning days. Voiselle lost the first of these encounters 4-2 despite a complete game two-hitter (Buddy Kerr’s two eighth-inning errors cost him two runs), but against the Pirates on the 26th, he finally broke through with his first big-league victory by going the distance in a 4-3, 10-inning win in the second game of a doubleheader at Forbes Field. The Giants had recorded their 91st loss in the opener — the most in franchise history — so it was becoming clear that Voiselle had a future in the starting rotation. His second straight four-hitter, this one a 1-0 loss to the World Series-bound Cardinals on the last day of September, reiterated such thoughts.

After a sparkling spring training in ’44, the New York Times reported that the “strapping right-hander from Ninety-Six, S.C.” had been tapped by Ott to start the April 18 season opener at the Polo Grounds. Still officially a rookie, he validated his manager’s confidence by going the distance with nine strikeouts in a 2-1 victory over the Braves. Then wearing # 17, the hurler known for his aggressive nature on the mound and a friendly, humble demeanor off it was an almost immediate sensation with sportswriters and fans forced to watch the lackluster Giants, who had finished dead last and 49 1/2 games behind St. Louis the previous year. He moved atop the National League pitching charts with three straight victories to begin the season, and sparked the “Ottmen” to an encouraging 7-3 record in April.

Poor defense and a lack of production from sources other than their home-run hitting player/manager plagued the Giants, however, and no pitcher was more snake-bit than Voiselle. He allowed just five earned runs in his next six starts, but 15 New York errors — many of them in the ninth inning of tight contests — resulted in 12 unearned runs and six straight losses. (His teammates scored just seven times during the span). One game from this miserable string stands out: May 23, when he started the first night game in New York since the city’s wartime blackout restrictions went into effect three years earlier. Bill lead 2-1 in the ninth inning at Ebbets Field, but lost 3-2 to the Dodgers after two of his teammates ran into each other in pursuit of a fly ball.

Better days lay ahead. Breaking the luckless skein with a three-hitter to top the mighty Cardinals on May 29, new bridegroom Voiselle (he married Virginia Elnora Bowlware on May 26) won five of his next six to reach a 10-7 mark by the end of June. The surprising Giants were hovering around .500 thanks to his efforts, and sportswriters from the normally austere Times kept coming up with inventive nicknames for the new ace. In one game account he was “the long, lean, lanky lad,” in the next he was “the husky from Ninety-Six.” Even in an era when complete games were much more common, his 17 full-distance efforts in his first 21 starts stood out. And while he wasn’t usually overpowering — seldom striking out more than five or six men, and usually walking four or five — he kept his underachieving club in almost every game. Even a propensity for allowing home runs did not seem to hurt him; he’d give up a record 31 for the year, but seldom would be beaten by them.

Although Big Bill cooled off a bit by mid-July, he was still picked by St. Louis manager Billy Southworth for the National League All-Star squad to replace injured Cards hurler Max Lanier. “Voiselle’s season record is eleven and ten, but might easily have been sixteen and five, for poor support has deprived him of at least six triumphs,” Roscoe McGowen of the Times declared when news of Voiselle’s selection broke. The season’s second half proved more of the same, as the Giants struggled through a 13-game August losing streak and the rookie phenom who stopped it continued piling up impressive wins and agonizing losses.

By the end of the year New York had fallen all the way to 67-87, but Voiselle stood out with a 21-16 record, a 3.02 ERA, and an NL-leading 312 2/3 innings, 161 strikeouts, and 41 starts. His win total and 25 complete games both ranked third in the senior circuit, and he was fifth in league MVP voting — just ahead of .347-hitting Stan Musial. There were no official Rookie of the Year awards given out until 1947, but the Chicago baseball writers who routinely honored freshmen players during this period picked Big Bill as the top newcomer of ’44. The Sporting News, then baseball’s leading journalistic voice, named him its “Pitcher of the Year.” No rookie has ever pitched 300 innings since, a record that is likely to hold up.

It looked like even bigger things were in store for Voiselle and his team in 1945. The right-hander began the season with a victory at Braves Field, and by the time he beat the Pirates 5-1 before 51,340 fans at the Polo Grounds on May 20, he was 8-0 and the first-place Giants were an incredible 21-5. Then, however, the winning inexplicably stopped for the ace — and New York.

Once again showing the hot-and-cold tendencies that would mark his entire big-league career, Voiselle suffered through his second six-game losing streak in as many years while the club endured an abysmal 5-18 stretch to drop out of first. Ninth-inning meltdowns were once again the culprit in many of Bill’s setbacks, but this time the problems were often of his own doing. Sportswriters chided the fallen ace in print for his failure to complete starts, and Ott’s attempts to use Voiselle in relief met with disastrous results.

After he finally got another win on June 24, the rest of Bill’s season was marked by dramatic inconsistency. In one 12-day stretch of July he threw a shutout against the Reds, was knocked out in the third inning by the Cards, beat the Cubs on a five-hitter, then was rocked over five-plus by the Pirates. By season’s end, while the rebuilding Giants had improved to a 78-74 record, Voiselle had declined to a so-so 14-14 mark with a swollen ERA of 4.49 (worst by far of New York’s four primary starters). His strikeouts and complete games were both way down from his rookie totals, and he allowed an alarming 249 hits and 97 walks in 232 2/3 innings.

The next season was even worse; the Giants regressed in 1946 back to 61-93 — a level of franchise futility topped only by the 98-loss club of ’43 — and Voiselle was just 9-15. His ERA did improve to 3.74, but he was no longer considered a top-flight starter. How had he fallen so quickly? Many point to a headline-making incident between the pitcher and manager Ott early in Bill’s ’45 slump. On June 1, Voiselle held a 3-1 lead with one out and one on in the ninth inning at St. Louis. He allowed a Johnny Hopp triple to bring in one run, and after getting his next man, had a one-and-one count on Ray Sanders when play was temporarily halted due to a windstorm.

Bill was still on the mound after the delay, but soon wished he wasn’t. Sanders tied the score with a single to short right, after which Whitey Kurowski promptly untied it with a game-winning triple to left-center. Following the game, the usually unflappable Ott announced he was fining Voiselle $500 for not “wasting” a pitch on Hopp — who had notched his three-base hit on an 0-and-2 count. Although Ott had previously warned all his pitchers he’d dock them $100 for not staying away from the strike zone under such circumstances, the added sting of a tough defeat likely prompted him to raise the ante on Big Bill.

Controversy brewed when Dick Young of the New York Daily News reported that Voiselle told him he had in fact thrown a “bad ball” to Hopp, who had done a fine bit of hitting to reach out and stroke it to left-center. There was, of course, no video or instant reply to consult, and other sportswriters took Bill’s side. (Among other things, he reportedly made just $3,500 at the time.) The public appeal worked, and on June 23 Ott announced he was returning the $500 to Voiselle. It didn’t help. Bill started that same afternoon against the Phillies, and allowed four hits and three walks in the first inning before Ott mercifully pulled him out. He did have some strong outings in the months and seasons to come, but Voiselle would never be a consistently dependable pitcher for this manager again.

Off to another lackluster start (1-4) in 1947, he was swapped on June 13 to the Braves along with an undisclosed amount of cash for another struggling young “former ace” — Mort Cooper. Fans and sportswriters speculated that the change in scenery might do Voiselle good. “Ott gives up nothing,” the Times’ Arthur Daley surmised in his influential column. “Southworth may get something.” Such hopeful prognosticators proved correct. Voiselle was an encouraging 8-7 over the remainder of the 1947 season, and in 1948 spring training Southworth predicted he could win 20 games.

By now the big right-hander had already become a favorite topic for photographers after receiving permission from Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler to wear No. 96, and he was soon making news with his arm as well. He got off to a stellar start reminiscent of his rookie year, notching a pair of shutouts and a 4-0 mark in his first four games to help Boston to the top of the National League. On July 10 he was 10-6, still among the league leaders in victories and on pace to achieve his manager’s earlier forecast. Voiselle, and not struggling left-hander Warren Spahn, was the man alongside Johnny Sain at the top of the Braves rotation. [It’s unclear whether Voiselle decided on his own to ask for # 96, or if Braves PR director Billy Sullivan or someone else thought up the creative idea.]

Then, as the pennant race moved into its final two months, Voiselle suddenly went cold. He lost 7 of 10 decisions to fall to 13-13, and after a 4-3 setback to the Phillies at Braves Field on September 4 was pulled from the rotation. With Sain proving the best pitcher in the league and Spahn regaining his own 20-win form of ’47, Southworth had decided to ride these two horses as much as possible down the stretch. Bill never drew another start after the Phillies game, just a few relief appearances at the end of the year. Despite his decent overall ERA of 3.63 compiled over 215 2/3 innings, he was an afterthought as the Braves held off Brooklyn and St. Louis to win their first NL championship in 34 years. The poem by Boston Post sports editor Gerald Hern that first appeared that month didn’t help. It read, in part: “First we’ll use Spahn, then we’ll use Sain, Then an off day, followed by rain.”

Poem or no poem, Southworth knew the team never would have been in position to win without Voiselle’s earlier success. The manager still had quiet confidence in Big Bill’s arm, and in the third game of the World Series he called on him in a very tight spot. Boston trailed the Indians 2-0 in the fourth inning of Game Three at Cleveland when Southworth yanked rookie starter Vern Bickford with one out and the bases loaded. Voiselle came in, got the dangerous Dale Mitchell on a foul out to third, and then ended the inning by retiring slugger Larry Doby on a groundball back to the box. Cleveland’s next seven hitters also went down in order, and while the game’s score stayed the same, Big Bill’s final line of 3 2/3 innings, one hit, and zero walks boded well for future Series work.

When it came, that work was on the grandest stage. The Braves faced elimination entering the sixth contest at Boston, and Southworth — feeling that Game One and Four starter Sain needed one more day of rest, and knowing Spahn was unavailable after pitching long relief the day before — gave Voiselle the ball. The move was questioned in a must-win situation (even a tired Sain, some surmised, would be a more formidable choice), but “Ol’ 96” gave a noble effort. He was so jacked up before the game that he was seen at 10 AM in full uniform on the grass at Braves Field, checking the wind currents. Seeing that the ballpark’s familiar gusts were heading out toward left, he likely feared that Cleveland’s right-handed power hitters would take advantage. Still, he matched Indians ace Bob Lemon pitch for pitch in the early going, and the score was 1-1 through five innings at Braves Field.

Then the wind helped do him in. Righty slugger Joe Gordon led off the Indians sixth with a home run to deepest left, and a walk, single, and infield out quickly brought in another run to hush the crowd of 40,103. Now down 3-1, Bill pitched a perfect seventh before giving way to Spahn and finishing his day with a solid line of seven hits, two walks, and three runs allowed. The Indians scored one more off Spahnie in the eighth, and when the Braves fell just short in their late-game comeback, it was Voiselle who took the 4-3 loss. His year had ended on the dourest of notes, but Big Bill could take solace as he collected his healthy $4,570.73 loser’s share and headed home to South Carolina. His ERA over 10 2/3 Series innings had been a very solid 2.53, and he had made a good case for a return to the rotation in 1949.

He did earn back his starting spot the next spring, but Voiselle was again plagued by old problems as he turned 30: inconsistency and bad luck. He beat the Dodgers with a three-hitter on April 25 for his first win, but was shelled by the Giants in his next start and then lost a two-hitter to the Reds. Manager Southworth apparently saw something he didn’t like, because Voiselle next went three weeks without pitching before picking up a relief victory against the Dodgers on May 28. Two days later he started and went eight innings for a win against the Phils, raising his record to 3-1, but now Southworth sat him down for a month before granting him another start. Again Big Bill showed his stuff with a four-hitter vs. the Giants, but when he was routed by the same club four days later he was shown the bench once more.

By late August Voiselle’s record was just 6-3, with four of his victories by shutouts. The Braves were floundering around .500 in what would prove an unsuccessful championship defense, and Spahn, Sain, and Bickford had become the unequivocal “Big Three” of the rotation. Other hurlers like 19-year-old bonus baby Johnny Antonelli and forgettable lefty Jumbo Elliott were getting some of Bill’s starts, and by now even a gentle giant like Voiselle had reason to be fuming. Southworth’s decision to temporarily step down on August 16 due to exhaustion (or a breakdown, depending on the source) was likely celebrated by the folks back in Ninety-Six as another chance at redemption for their hero — who that very year brought some of his big-league friends home and put together a benefit exhibition game for Jackie Spearman, a local woman battling cancer. Interim manager Johnny Cooney did indeed put Voiselle back into a regular rotation slot, but he failed to make the most of it — going 1-5 down the stretch to finish with a 7-8 record and a 4.05 ERA.

When reports broke that Braves players had voted Southworth just a half-share of their fourth-place bonus money, it was assumed that Voiselle was one of those voting in the majority to stiff their former-and-future skipper. In post-mortem discussions of the season, with Southworth due to come back, Big Bill was one of those deemed expendable by the club. Rumors broke of interest from the Cubs, and on December 14 they were verified with Voiselle’s swap to Chicago for minor leaguer Gene Mauch and cash. An upbeat Southworth was quoted as saying, “We felt we could give up Voiselle, a possible starter, because I think we’ll be set with the addition of Norman Roy, who came up to us from Milwaukee.”

Southworth was right, to a point. Roy would win just four games in this, his only big-league season, but Boston still got the best of the deal. By May, Chicago Tribune writer Irving Vaughn had dubbed the new Cubs pitcher “hapless Bill Voiseille,” and after an 0-4 record and 5.82 ERA compiled over 19 outings, Ol’ 96 (he still wore the number) was sent to minor league Springfield (Mass.) on July 13. Less than two years after starting the biggest Braves game in 30 years, he had been unable to hold a job with the NL’s seventh-place outfit. Although his final major league record of 74-84 (and 3.83 lifetime ERA) had certainly not reached the level suggested by his rookie exploits, he knew he’d enjoyed higher highs than some hurlers with far better marks.

In most cases this would be the end of the tale, but Bill Voiselle was far from through with baseball. Pitching his home games less than two hours from Braves Field, he went 9-8 with the Triple A Springfield Cubs during the remainder of the 1950 season before being sold into the Brooklyn Dodgers system. He got into 47 games for Montreal in ’51, registering a solid 3.48 ERA for the second straight year, and then after one year off came back to spend parts of five more seasons in the high minors. In 1955, hurling for Triple A Richmond, he led the International League with a then-minor league record 72 appearances at age 36 and was briefly reunited with old Braves rotation-mate Vern Bickford. All told Voiselle pitched in 502 bush league contests bookending his 245 games in the majors, with an 88-110 slate more suggestive of longevity than excellence.

Even when his professional days finally ended after 11 appearances with Tulsa of the Texas League in 1957, Big Bill was hungry for more. He returned to his beloved Ninety-Six with his wife, Virginia, and teamed up again with brothers Jim and Claude on the town’s mill club in the semipro Central Carolina Textile League. When he wasn’t playing himself, he continued helping organize local charity games. On the mound, he certainly didn’t take himself too seriously anymore; on one occasion, after an opponent had collected two straight hits off him, he delivered something different to the plate on the batter’s next time up: his glove. As Voiselle laughed with delight, the batter belted a solid line drive.

Because of his fame as “Ol’ 96,” the town celebrity drew far more interest from autograph seekers than most hurlers sporting a sub-.500 lifetime mark in the majors, and he briefly resurfaced in headlines when pitchers Williams and Wendell took to wearing No. 99 in the 1990s. A few years earlier, Bill traveled to Boston for the 40th reunion of the ’48 Braves champions put on by the New England Sports Museum, but most of the time he stayed close to home. “He was a real caring person to all us kids,” his nephew George Voiselle recalled. “Teachers would have him talk to students, and he never turned anybody down.”

Voiselle also never won a World Series, but was honored by the South Carolina House of Representatives in 2001 for bringing “honor and glory to the State of South Carolina” through his athletic and charitable endeavors. “Everything I got, I owe it to baseball,” Voiselle once told Sports Collectors Digest. “I’m a little ol’ cotton mill boy — never had nothing and never been nowhere.” In the end he got quite far on his pitching, but wound up right back where he started and most wanted to be.

“He was just a wonderful guy, and everybody loved him to death,” longtime neighbor Bubba Summers stated in one tribute published upon Voiselle’s death two days after his 86th birthday in 2005. “If you didn’t know him, you really missed out.”

For Summers, and the other folks in Ninety-Six, Bill Voiselle was far more than just a number.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Sources

Obituary appearing in Feb. 2, 2005 edition of Index-Journal newspaper in Greenwood, S.C. (found on www.thedeadballera.com)

Obituary on www.historicbaseball.com

Assorted Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, Christian Science Monitor, Hartford Courant, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Associated Press, and United Press International articles, 1942-1984.

Obituary at www.retrosheet.org

Stats from www.Baseball-reference.com and baseballray@aol.com

Kelley, Brent. “Bill Voiselle Was Key Member of ’48 Braves”, Sports Collectors Digest, July 19, 1991.

Graham, Frank. The New York Giants — An Informal History of a Great Baseball Club (Carbondale IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002 — reprint of 1952 book)

Author tribute to Voiselle, “Farewell to Ol’ 96,” appearing in Boston Braves Historical Association newsletter, spring 2005

Full Name

William Symmes Voiselle

Born

January 29, 1919 at Greenwood, SC (USA)

Died

January 31, 2005 at Greenwood, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.