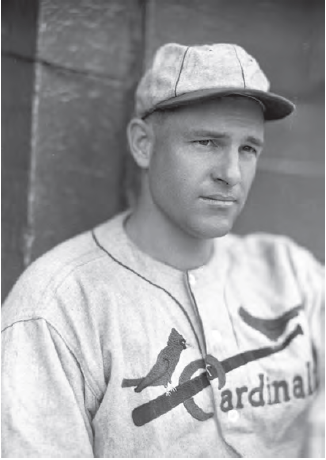

Jack Rothrock

Jack Rothrock, a solid outfielder for the 1934 Cardinals, played every position there was for the Boston Red Sox in 1928, a year in the middle of a good long run (1925-1932) for a really bad team. The versatile outfielder played 639 games in the outer garden in his eight major-league seasons, and more than 200 games in the infield between 1925 and 1930 (78 games at shortstop, 63 at second base, 48 at third base, and 38 at first). And in 1928 he caught in one game and pitched in one.

Jack Rothrock, a solid outfielder for the 1934 Cardinals, played every position there was for the Boston Red Sox in 1928, a year in the middle of a good long run (1925-1932) for a really bad team. The versatile outfielder played 639 games in the outer garden in his eight major-league seasons, and more than 200 games in the infield between 1925 and 1930 (78 games at shortstop, 63 at second base, 48 at third base, and 38 at first). And in 1928 he caught in one game and pitched in one.

Statistically, pitching is where Rothrock excelled – though with a tiny sample size. Motor City fans who came to the game on September 24, 1928, saw the Red Sox’ Sam Gibson throw a five-hit, 8-0 shutout for the Tigers. Rothrock played the outfield (left field) then the infield (shortstop), and pitched in the bottom of the eighth inning (without letting a runner reach base). He fielded his position well, credited with assists on two of the three outs. He’s in the record books, with a perfect 0.00 ERA, having retired all three batters he faced, and a 1.000 fielding percentage. His lifetime major-league batting average was a more pedestrian but still good .276.

Five days after his inning on the mound, Rothrock strapped on the “tools of ignorance” and caught the first inning on September 29 at League Park in Cleveland, playing his ninth field position of the season. Pitcher Danny MacFayden played left field in the bottom of the first (no Indians scored), and then left the game with Rothrock retreating to left field and Johnnie Heving moving in behind the plate. Slim Harriss got credit for Boston’s 6-5 comeback win. Rothrock committed an error while playing in left. He had no fielding chances in his inning serving as the catcher for starter Merle Settlemire. A versatile player indeed.

Jack Houston Rothrock was born in Long Beach, California, on March 14, 1905. “A lot of the newspapers called him John, but he was christened Jack,” said his son, Jack Jr. Jack Sr.’s father, Ray, was a motorman on the street railroad, a position he held for many years. Ray had come to California from Indiana, where his father had been a blacksmith. Ray was a schoolteacher at first, living with his aunt and uncle, but progressed to the possibly better-paying job of motorman. Apparently, Ray was also a competitive bicyclist at one point.1 Clara Law Rothrock, Jack’s mother, was either a Canadian or a Nebraskan depending on which United States Census one believes; Nebraska beat out Canada two to one. Her first-born was Ralph, four years older than Jack. Ralph found work as a mechanic.

Jack was a switch-hitter, the last one the Red Sox had from his April 1932 trade to the White Sox until Pumpsie Green joined the team in 1959. He threw right-handed – from the mound, from behind the plate, from all seven other positions. He was a half-inch shorter than an even 6 feet tall and is listed with a playing weight of 165 pounds. His first major-league game was on July 28, 1925. “I’d rather play ball than eat,” he told writers on his first day with the Red Sox. He’d begun his career in Organized Baseball just the year before.

Jack had played for Long Beach Polytechnic High School, but he’d also played semipro ball in the area and that cost him eligibility for his senior year of baseball for high school and all of college – forcing him to turn down scholarships from four colleges. He kept busy, playing shortstop for Bellflower over the winters of 1923-24 and 1924-25, before and after his first year in Organized Baseball (1924), playing in the Class D Southwestern League for the Arkansas City (Kansas) Osages. Rothrock was 19 and played in 120 games, batting .314. He played shortstop and had three homers, 19 doubles, and six triples.

He may have played one year earlier, in 1923. According to a lengthy feature on Rothrock, he initially signed with the Hutchinson Wheat Shockers of the Southwestern League. Manager Marty Purtell was the shortstop as well, and was hurt and on the bench when Jack arrived. He played a few games at short but when Purtell got better, it was Jack riding the bench. Later in the season, he was sent to the Topeka Kaws in the same league but wasn’t needed at all there. Hutchinson sold him to Arkansas City.2

In 1925 Rothrock reprised with Arkansas City and boosted his average to .337, upping his extra-base totals across the board. In mid-June, Boston Red Sox president Bob Quinn couldn’t know what his end-of-year totals would be; in fact, when he announced that he’d signed Rothrock to report at the close of the minor-league season in September, the Boston Globe reported that his average wasn’t known at the Red Sox headquarters, “but reports received there were to the effect that he is hitting better this year than he did last.”3 He’d been recommended to Quinn by Steve O’Rourke of St. Marys, Kansas, who had earlier recommended infielder Billy Rogell to the Red Sox. Scouts from three or four teams had their eyes on Rothrock, and one just missed. Walter McCredie of the Detroit Tigers turned up just after Jack had signed; had he been just a bit earlier, bird dog Ed Teck would have earned a $500 bonus. It had been Teck who had landed Rothrock the job with Arkansas City.4 Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote an appreciation of Rothrock after his death, and said he’d been signed “out of a softball game in which he’d shown aggressive base running and sliding – on concrete.”5

The Red Sox decided not to wait until September, and Rothrock joined the team in Chicago on July 21, assigned to be pitcher Red Ruffing’s roommate. He played in his first game on July 25, and it was a blowout of a game in Boston, with Tris Speaker’s Cleveland Indians winning, 16-7. Rothrock came into the game late at shortstop, and in his only at-bat he rolled out to pitcher Sherrod Smith, but impressed fans with how quickly he made it down the line. He’d done well in the 100-yard dash at Long Beach, and was exceptionally fast – widely considered the fastest man in baseball at the time. More than one article dubbed him Baseball’s Charley Paddock – a reference to the world record holder in the 100-meter race (who held the record for more than 30 years). A newspaper clipping in his son’s possession told of when Paddock and Rothrock ran against each other from left field to home plate. Paddock crossed the plate perhaps eight inches ahead. Paddock reportedly told Jack that if he’d trained as a runner instead of playing baseball, Paddock might well have lost. Grantland Rice ran a letter from a reader who told about Paddock giving Rothrock a five-yard handicap during a race in Los Angeles and the two of them running even.6

Rothrock had an exceptionally good first year, filling in when he could, getting into 22 games and batting .345 in 55 at-bats. His first hit, a double, came in his third game, when he pinch-hit and took over at shortstop. His first start was the next day, August 4, and he collected his first run batted in. The 1925 Red Sox were so bad that it was only in Rothrock’s tenth game that he enjoyed the pleasure of seeing the team win a game that he’d played in. It was a 5-1 win over the New York Yankees at Fenway Park on September 7, some six weeks after his debut. His top batting performance that year was his last, a 3-for-5 day with a three-run triple on October 2 against the visiting Washington Senators. He was shaky in the field his first year, committing nine errors, all at shortstop, for an .893 fielding percentage.

It was around this time that Jack married his high-school sweetheart and high-school classmate, Vivian Viola Anspach. Jack Jr. was born in 1930 and daughter DeAun came later. Some years later, Jack and Vivian divorced.

New Orleans hosted Red Sox spring training in 1926, Rothrock’s first with the club. He made the team as a utilityman and stuck with Boston the first month and a half of the season, pinch-hitting and doubling in a run against the Yankees on Opening Day. In June he was placed with the Rochester (New York) Tribe of the International League, subject to 48-hour recall. He played 84 games, mostly at second base, batting .302, and was called back just in time to get into one last Red Sox game. He hoped to become a regular in 1927 and hoped to play shortstop.

A full year of work saw Rothrock as a sort of super-utility player in ’27; he appeared in 117 games somewhat evenly spread among all four infield positions. For whatever reason, his average plummeted from .294 to .259, precisely the team average for the season. He scored 61 runs and drove in 36.

In 1928 Rothrock broadened his palette, playing all nine positions, three of them in the one September 24 game. To fit all the information into the AP box score as it appeared in the Washington Post, a radical contraction of Jack’s last name was in order: R’k lf, ss, p. His average nudged up slightly (.267), in exactly the same number of games. He was again second fiddle at every position, an invaluable utility player.

For 1929, Rothrock finally became a regular. He was the team’s center fielder, the better to take advantage of his speed and his strong arm, and he played in 143 games. But manager Bill Carrigan didn’t hesitate to move him around as the situation dictated. An example would be a July 2 game against the Yankees. With Babe Ruth up, Rothrock replaced Elliot Bigelow in right field and made a running catch of Ruth’s long fly ball. Then he was moved to center, switching positions with Ken Williams, and he pulled in Tony Lazzeri’s fly after a good long run. He hit an even .300, the highest average among any of the Red Sox regulars, and stole 24 bases. Both were career highs.

Rothrock entered 1930 full of hope for the year to come, looking to build on his 1929 season. Just as it seemed that he had arrived, he broke his leg in the season’s fourth game sliding into second base in the seventh inning. He didn’t return until July 9, and when he did, he was almost exclusively used for pinch-hitting duties. (He didn’t start another game until September 25.) He hit .277.

In 1931 Rothrock appeared in 133 games, starting most of them as the left fielder, but was also brilliant as a pinch-hitter, reaching base nearly 50 percent of the time: 9-for-20 and one base on balls. His batting average was essentially the same as in 1930, one point higher. In his years with the Red Sox, he pinch-hit safely 27 times.

The Red Sox did two deals with the White Sox on April 29, 1932. They traded catcher Charlie Berry to Chicago for outfielders Smead Jolley and Johnny Watwood and catcher Bennie Tate. In a separate deal, Rothrock was moved to the White Sox for the waiver price of $7,500. He’d been in 12 games for the Red Sox before the trade, batting .208. Oddly, he started the season with a nine-game hitting streak; only in his 10th and 12th games did he fail to collect a hit. For the White Sox, there was an adjustment period. In his first 28 games, Rothrock managed only three hits, though he didn’t have as many opportunities since much of his work was in pinch-hitting. After June 11, batting .088, he was sent to Toronto, where he recovered, batting .327 in 79 games. He came back to Chicago on September 5 and hit well enough to add an even 100 points to his average.

A month after the season, on November 2, Rothrock and infielder Carey Selph were sent to St. Louis to complete a deal with the Cardinals made on September 11 when they sent outfielder Evar Swanson to the White Sox.

Rothrock spent all of 1933 in the American Association, playing for the Columbus (Ohio) Red Birds, and he had an excellent year that The Sporting News called a “stirring comeback” (even though the article got the year wrong). He was named to the league’s All-Star team.7 He hit .357 with 11 home runs, and then was a big factor in Columbus’s defeating Minneapolis in the American Association playoffs and then Buffalo in the Little World Series.

Rothrock’s play earned him a trip back to the majors with the Cardinals in 1934 – and he had a terrific season. Not a great deal was expected of Jack. He was one of the contenders to take over right field from George Watkins, traded to the Giants near the end of March. The Cardinals were always pretty strong in those days, but they had finished sixth in 1932 and fifth in 1933. Second baseman Frankie Frisch had taken over as player-manager in mid-’33. Some saw the Cardinals as having an “outside chance” to grab the 1934 NL flag, but the reigning world champion Giants and the Cubs were probably better bets.

The Cardinals did have pitching, though, and three of the first five batters in the batting order were switch-hitters. After a 2-7 start, the team won 12 of 13 in early May and advanced from seventh place to within a half-game of the league lead. The last of the 12 wins was the third in a row taken from the Giants, won in the bottom of the tenth by Rothrock’s bases-loaded single.

Rothrock became a big part of the St. Louis Gas House Gang as the team made it into, and won, the World Series. He generally batted second and played in every single game – the team carried only 21 players that year. “I had to play every day,” he told Robert L. Burnes of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. “There wasn’t anybody to take my place.”8

Rothrock posted personal bests in runs scored (106), RBIs (72), and home runs (11), and hit .284. His average was a bit below the team’s .288 mark and he wasn’t tops on the team during the regular season in anything other than games played, at-bats, and plate appearances, but he was a solid contributor. Forty-nine of the team’s 95 wins were due to the pitching Deans. Dizzy Dean’s 30-7 record on the mound and Ripper Collins’ 128 RBIs were the key individual stats. Diz’s younger brother Paul had started off his rookie year 10-1, and finished 19-11. In the World Series against Detroit, Jack hit only .233 but it was a very productive .233 – he accounted for three of the team’s four runs in Game Three’s 4-1 win. Rothrock tied for the team lead in doubles and extra-base hits, and (most importantly) led in runs batted in, with six. His fielding was “steady to the point of brilliance,” in the words of J. Roy Stockton of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.9 Jack played every inning of every game in the Series, too.

As the Cardinals were celebrating their lopsided 11-0 win over the Tigers in Game Seven, Miss Jackie Coogan (“a show girl”) filed a lawsuit in Boston demanding that Rothrock return to her a $500 diamond ring she claimed she had entrusted to him at a party two years earlier. Rothrock’s counterclaim said that the ring wasn’t hers.

The 1935 season was a good one, too, though it got off to a very slow start. It was Jack’s 12th year in Organized Baseball. He hit .273 with three homers and 56 RBIs, a bit of a decline. The Cardinals finished in second place, four games behind the Cubs. The team was ready to turn right field over to Pepper Martin. Rothrock had now turned 30 and after the season was over he passed through waivers – not one team claimed him – and was released to Rochester, back again in the minor leagues. It was with a bit of tongue in cheek that New York sports scribe Tom Meany wrote that Rothrock “is being overcome with the infirmities of senility.”10 Jack was studying civil engineering in the offseason and contemplated quitting the game. He relented and played for the Red Wings in 1936. Maybe he was getting old; his .299 batting average was the first time he’d come in under .300 in a minor-league season.

In August 1936, Jack changed affiliations once more. He was traded to the Cincinnati Reds for outfielder Sammy Byrd, but Byrd elected to retire to become a golf pro. That left the Reds needing to either make a fresh deal to keep Jack or return him to Rochester. They returned him, and Rochester turned around and sold him for an undisclosed sum to the Philadelphia Athletics on April 16, three days before the season began.11

It was Jack’s last season in the majors, back where he began, in the American League. He was still only 32, but at least one article included him in a list of “aging ballplayers” looking to make a comeback.12 Rothrock played in 88 games, hitting .267 as a utility outfielder. In his 11 seasons of major-league ball, he’d hit safely 27.6 percent of the time, driven in 327 runs, and scored 498 times. As soon as the season was over, he was purchased by Indianapolis of the American Association, but he refused to report. He wanted to play on the West Coast, and the Los Angeles Angels worked out a deal in March 1938 to buy his contract from Indianapolis. Jack spent the next three seasons in the Pacific Coast League. The first two-plus were for the Angels in 1938 and 1939; a knee injury the first year and a lame leg the next limited his playing time a bit. It’s too bad when facts get in the way of a good story. Los Angeles Times columnist Bob Ray wrote on September 30, 1939, that Jack had a $10 bet with teammate Lee Stine that he’d hit .300. As Ray told it, there were two outs when Jack came up to bat in the ninth inning of the final game of the season. Stine was on second base at the time – and got picked off. Game over. The trouble with the story is that Rothrock’s final average was .292. That December, Stine purchased the house next door to Rothrock’s Lakewood Village home.13

Before the end of 1939, Rothrock asked the Angels for his release so he could play for the Hollywood Stars, managed by his old Red Sox teammate Bill Sweeney. No dice, at first. He opened the 1940 season with the Angels, but was released on April 30 when the team needed to cut down to the player limit. He signed on with the Stars in mid-July, and finished the year with them.

In 1941 Rothrock turned to managing, handling the San Bernardino Stars, a New York Giants team in the Class C California League. The team disbanded on June 29. Before they did, he got in his last ten games as a player, hitting .444 in 18 at-bats, but going 0-2 when he tried his hand at pitching a couple of final times. During the war years, he performed “government engineering work in the Los Angeles Harbor area, after he was obliged to close his profitable café, which was in a vital defense zone.”14 “He owned a restaurant down on the Navy landing in Long Beach,” said his son. “And he had two cabin cruisers. Dad had an offer to go in the Coast Guard because of the fact that he had these cabin cruisers and been familiar with navigation in the area, but he had to get my mother’s permission to go and she wouldn’t give it to him. He went into the Army Engineers and helped build some of the gun emplacements along the West Coast here. He came home almost crying one day because they put one on the 15th green of a very beautiful golf course.”15

From 1947 through 1950, Rothrock managed again – first with the Sunset League’s Anaheim Valencias, where he saw the team leading the league but was fired because the owners wanted to economize by having a playing manager. Two days later, he was hired by the Riverside Dons, who wound up finishing ahead of Anaheim by one game. (Anaheim got its revenge in the playoff finals, defeating Riverside four games to one.) He skippered the Tallahassee Pirates in the 1948 Georgia-Florida League, and then San Bernardino again in 1949. His last season as a manager – and in baseball – was in Virginia with the Big Stone Gap Rebels of the Class D Mountain States League. “Big Stone Gap is coal-mining country, and these coal miners would come out of the mines and they just went wild,” said Jack Jr. “The ballpark was set up by scraping the top of a mountain and flattening it out. The clubhouses were down on the side. One of the guys struck out with the tying run on third and the winning run on second, and he went down to take a shower and heard a couple of plunks. They were up on the mountainside shooting down through the opening in the clubhouse.”16 It was time for other pursuits.

Rothrock was versatile in his choice of offseason and post-baseball occupations, too. Though originally involved in insurance, he’d been working as a necktie salesman during the offseason in Columbus before his 1934 season with the Cardinals. After the 1935 season, he joined a barnstorming tour in California. In 1937 he worked in real estate and built a house for Red Ruffing. He played winter ball, and even ran a basketball team in Long Beach for a couple of winters. In February 1940, a news clipping reported that he had “branched out from a Long Beach, Cal. restaurateur to a hotel man,” taking a five-year lease on the Pickwick Hotel in Anaheim.17

For many years Rothrock worked with the city of San Bernardino Parks Department until retirement. Jack Jr. explained, “He was in the firefighting area. Dad was not a firefighter per se. He worked in the office. The only thing Dad did as far as athletics go was to work in Little League.”

Rothrock died of a heart attack on February 2, 1980, in San Bernardino. He left behind his wife, Ardith; Jack Jr. (a 28-year Marine Corps veteran who served both in Korea and Vietnam); a daughter (DeAun Pyka); and a stepdaughter (Norma Casper).

An updated version of this biography is included in “The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals The World Champion Gas House Gang” (SABR, 2014), edited by Charles F. Faber.

Sources

Interview with DeAun Pyka on December 29, 2009, and with Jack Rothrock, Jr. on December 30, 2009.

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the online SABR Encyclopedia, retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Los Angeles Times, April 17, 1940.

2 Christian Science Monitor, August 22, 1935.

3 Boston Globe, June 23, 1925.

4 Los Angeles Times, July 26, 1925.

5 February 1980 clipping in Rothrock’s Hall of Fame player file.

6 Atlanta Constitution, May 16, 1929.

7 The Sporting News, February 22, 1934.

8 1980 clipping in Rothrock’s Hall of Fame player file.

9 The Sporting News, December 19, 1935.

10 New York World-Telegram, December 5, 1935.

11 The Sporting News, April 22, 1937.

12 Los Angeles Times, February 26, 1937.

13 Los Angeles Times, December 19, 1939.

14 Unattributed February 26, 1942, clipping in Rothrock’s Hall of Fame player file.

15 Interview with Jack Rothrock, Jr. on December 30, 2009.

16 Jack Rothrock, Jr. interview.

17 Los Angeles Times, February 12, 1940.

Full Name

Jack Houston Rothrock

Born

March 14, 1905 at Long Beach, CA (USA)

Died

February 2, 1980 at San Bernardino, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.