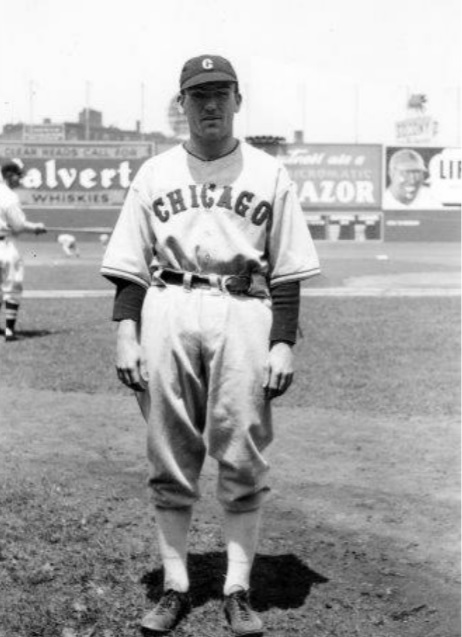

Bill Dietrich

Hard-throwing right-hander Bill Dietrich battled wildness, struggled with his temper, and endured chronic elbow pain that resulted in two operations to fashion a 108-128 record and log in excess of 2,000 innings in parts of 16 injury-plagued big-league seasons (1933-1948) while playing for primarily second-division clubs. Twice waived out the American League in 1936, Dietrich signed with the Chicago White Sox, with whom his career was revived by skipper Jimmy Dykes and coach Muddy Ruel. The following season Dietrich seemed like an unlikely candidate to throw a no-hitter; however, two days after surrendering 10 runs and 14 baserunners in a disastrous 3⅓-inning start, Dietrich ignored his bloated 10.13 ERA to hold the St. Louis Browns hitless on June 1 at Comiskey Park.

A lifelong resident of Philadelphia, William John Dietrich was born on March 29, 1910, in the City of Brotherly Love. His Pennsylvania-born parents of German ancestry were Charles, an accountant, and Berth (Hopes) Dietrich. The family also had an older son, Charles, and a younger daughter, Mable. By all accounts Bill was a small and unathletic child who began wearing glasses by the age of 8. Despite weighing only about 115 pounds when he enrolled in Frankford High School in the Near Northeast Side of the city in 1925, Bill tried out for the freshman baseball team. “I was not much good [as an infielder],” recalled Dietrich, “but it was noticed that I could throw the ball hard. I was advised to take up pitching … and my progress was quick.”1 Aided by a growth spurt that packed about 60 pounds onto his eventual 6-foot frame, young Bill became one of the best athletes in school history. He lettered in football, basketball, and baseball for three years each, and developed into one of the area’s best hurlers. As a senior in 1929 he led his high-school nine to the Philadelphia Public League championship, fanning 20 batters in a 13-inning complete game and scoring the winning run in the title game.2 By that time, scouts from big-league teams routinely watched him pitch. After graduating, Dietrich worked out at Shibe Park at the invitation of Athletics manager Connie Mack, who signed him to a contract for the 1930 season. Dietrich supposedly rejected more lucrative offers from both the New York Giants and the New York Yankees to sign with the reigning champions.3

After competing in various semipro leagues in the summer and fall of 1929 and during an abbreviated college experience at Villanova, Dietrich joined the A’s in spring training in Fort Myers, Florida, in 1930. Practicing with the likes of 20-game winners Lefty Grove and George Earnshaw, the teenage Dietrich held his own. Mack, who thought the youngster could benefit by being around big leaguers, took an unorthodox approach by retaining Dietrich as a batting-practice pitcher at home game during the season, instead of optioning him to the minors. Dietrich continued hurling in Philadelphia’s semipro league the entire season.

Dietrich’s career in Organized Baseball officially got under way in 1931 when he was optioned to the Harrisburg Senators of the Class-B New York-Pennsylvania League after participating in spring training with the big-league club. En route to an 18-11season and a sturdy 2.89 ERA (but also 130 walks in 209 innings) for the league champions, Dietrich tossed a no-hitter on June 6 against Wilkes-Barre in just his eighth professional start.4

Described by the Harrisburg Telegraph as possessing an “extremely fast ball” but also being “very erratic,” Dietrich began the 1932 season with the Portland Beavers in the Double-A Pacific Coast League.5 In mid-July, sporting a 5-7 record, Dietrich was sent back to the New York-Penn League (by one account he asked to pitch closer to home),6 where he twirled for Wilkes-Barre, winning nine of 13 decisions.

In spring training with the A’s for the first time in two seasons, the 23-year-old Dietrich impressed Connie Mack with his speed, and broke north with the club to start the 1933 season. He debuted in the second game of the campaign, on April 13, relieving Earnshaw with one out in the sixth inning at Washington. He yielded three hits and two walks to the five batters he faced, and was charged with three earned runs in a forgettable outing. It didn’t get much better for the native son, who was optioned to Montreal in the Double-A International League in late May. Despite struggling north of the border (5.19 ERA and 104 walks in 156 innings), Dietrich returned as a September call-up to the A’s, who finished in third place with 79 wins, their lowest total since 1924.

Mack, whose primary income was his baseball club, continued dismantling the team in light of the financial hardships brought on by the Great Depression. After selling Al Simmons to the Chicago White Sox after the 1932 season, the “Tall Tactician” dealt two more future Hall of Famers after the ’33 season: Lefty Grove to the Boston Red Sox and Mickey Cochrane to the Detroit Tigers. Mack counted on Dietrich to shore up a young, inexperienced staff that included two first-year players who had respectable seasons: Johnny Marcum (14-11, 4.50 ERA) and Joe Cascarella (12-15, 4.68) and three-year veteran, Sugar Cain (9-17, 4.41). Dietrich got off to a horrible start (10 runs in 10⅔ innings of relief), then lacerated his right thumb on a bottle in mid-May. According to sportswriter Frank Reil, Dietrich was on the verge of being optioned when he pitched a complete-game four-hitter to pick up his maiden big-league victory, 4-2 over the St. Louis Browns.7 Frustratingly inconsistent, Dietrich was either very good (he tossed four shutouts, including a sparking two-hitter against Washington in his next to last start of the year) or horrible. He surrendered at least five earned runs in 11 of his 23 starts, including 11 in a complete-game loss to the Yankees. He finished with an 11-12 record and a 4.68 ERA in 207⅔ innings, and issued a career-high 114 free passes for the fifth-place A’s. Twice that season he walked a career-high nine batters; one of those games was on July 28 against the Yankees, whom he defeated in a distance-going outing, 4-3, despite yielding 17 baserunners.

Dietrich was among the few players who wore spectacles, and rarely did a sportswriter refer to him without mentioning his cheaters. Like Will White of Cincinnati in the American Association in the 1880s and later Lee Meadows of the National League (1915-1929), widely considered the first pitchers to don glasses on the mound, Dietrich’s glasses were not shatterproof. Luckily he was never hit in the face by a batted ball. “I had my cap knocked off lots of times,” recalled Dietrich. “Line drives would come so close to my ear that they would actually draw blood.”8 Throughout his career, Dietrich was known as “Bullfrog,” given his moon-shaped face punctuated by his round eyeglasses.

Dietrich slipped to 7-13 in 1935 as the A’s finished in last place for the first time since 1921. “[He] had a very bad year, both as a starting pitcher and relief pitcher,” opined Philadelphia sportswriter James C. Isaminger.9 Of Dietrich’s 18 starts in a career-best 43 appearances, five came within a 20-day span in August. A six-hit shutout against Cleveland at League Park IV on August 22 was sandwiched between four losses during which he yielded 30 runs in 32 innings. In the final of those defeats, Dietrich surrendered career highs in runs (13), earned runs (11), and hits (17), and also walked eight in a loss to Detroit. Dietrich’s 5.39 ERA (in 185⅓ innings) was the third-highest in the AL.

Dietrich’s big-league career was in peril in 1936. An exasperated Mack finally cut ties with the walk-prone “problem child” of his staff, placing Dietrich on waivers about a week after the right-hander tossed 11 innings of relief against Chicago on June 19, yielding only two unearned runs in the 13th inning to lose the game.10 Despite Dietrich’s unsightly 6.53 ERA in 71⅔ innings, the Washington Senators claimed him. Dietrich made only five ineffective relief appearances (nine earned runs in 8⅓ innings) before he was given his outright option to Albany of the International League. Unexpectedly, the Chicago White Sox blocked the move by claiming him off waivers. Thrust into the starting rotation, Dietrich tossed a complete game in his first start in a 19-6 drubbing of the A’s, then blanked the Boston Red Sox on two hits in his next start.

Notwithstanding Dietrich’s dismal 5.75 ERA in 162⅔ innings for three teams in 1936, Chicago skipper Jimmy Dykes and his trusted coach Muddy Ruel saw a reclamation project. Ruel, a former catcher, thought that Dietrich’s wildness resulted from clenching the ball too tightly, and suggested a lighter grip. That advice helped Dietrich harness his control enough to be a productive hurler for the next decade despite two elbow operations and a host of other injuries.

While Ruel worked on Dietrich’s mechanics, Dykes addressed his attitude. Dietrich had a reputation as a hothead. “[He] had one of the worst tempers in baseball,” said Dykes. “It was the thing that beat him day after day. … I told him I thought he had the makings of a great pitcher except for his temper. ‘You break your temper or I’ll break you,’ I said to him.”11 Dietrich responded to Dykes’s tough love and reined in his temper.

Dietrich got off to a dismal start in 1937, suffering from flu-like symptoms and sinus problems. On May 29 Cleveland assaulted him for nine hits and 10 runs in just 3⅓ innings, raising his ERA to 10.13 in 16 innings. Undeterred by the humiliating loss, Dykes sent the Bullfrog back to the mound on two days’ rest to face the St. Louis Browns at Comiskey Park on June 1. Defying expectations, Dietrich tossed the game of his life, a headline-grabbing no-hitter, and issued just two free passes. The victory was part of what Chicago sportswriter Irving Vaughn called a “sensational spurt” of 10 consecutive wins that catapulted the White Sox into a tie with the Yankees for first place on June 8 and ignited pennant fever.12 The team eventually settled for third place and 86 victories, their best marks since 1920 when the Black Sox scandal broke. Dietrich, bothered by a sore elbow most of the season, went 8-10 and carved out a 4.90 ERA in 143⅓ innings.

In the offseason Dietrich underwent surgery on his right elbow to remove bone chips and growths. The presiding surgeon, Dr. Phillip H. Kreuscher of Philadelphia, expected the hurler to be able to pitch in 1938. However, Dietrich’s recovery was slow and his elbow swelled every time he threw. By mid-June Dietrich had made only eight mostly ineffective appearances (5.44 ERA with 31 walks in 48 innings) and was placed on the voluntarily retired list a month later.13

In the next two seasons Dietrich saw action primarily as a spot starter and occasional reliever as the White Sox recorded consecutive fourth-place finishes. He went 7-8 (5.22 ERA in 127⅔ innings) in 1939, then enjoyed his first winning season (10-6) with a more respectable 4.03 ERA in 149⅔ innings in 1940. In the last five weeks of that season, a finally healthy Dietrich flashed the kind of heater that once made Connie Mack compare him to Walter Johnson and Lefty Grove. In his best stretch of ball since 1934, the Bullfrog completed four of seven starts, relieved once and posted a stellar 2.44 ERA in 66⅓ innings.

In an oft-repeated refrain in White Sox history, the 1941 club was characterized by the league’s lowest-scoring offense and stingiest staff (3.52 team ERA). The result was a .500 record, yet a third-place finish. The mound corps included All-Stars Thornton Lee (22-11, with a league-leading 2.37 ERA and 30 complete games) and Eddie Smith, as well as 40-year-old Sunday hurler Ted Lyons. Dietrich, described by Stan Baumgartner in The Sporting News as one of the “backbones” of the squad, took the mound on Opening Day in front of more than 46,000 partisan fans at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium to face off against Bob Feller, coming off a 27-win season.14 In the second inning, Feller hit Dietrich with a fastball on his right elbow. “Closest call I ever had,” recounted Dietrich years later. “I just got my hands up to protect my face.”15 Courtesy pinch-runner Don Kolloway took first while trainers tended to Dietrich. Surprisingly, Dietrich came back to the mound the next inning and outdueled Bullet Bob, spinning a seven-hitter to win, 4-3. Never one to back down, Dietrich also plunked Feller, in the fifth with a changeup. Apparently feeling no ill effects from Feller’s errant throw, Dietrich held Detroit hitless for 8⅓ innings in an eventual 6-3 victory in his next start. But bad luck always seemed to find Dietrich, who the Chicago Tribune suggested was a “child of repeated misfortune.”16 One start after yielding only a fourth-inning single in a shutout against the Browns on May 29 for his fourth victory of the season (all by complete game), Dietrich injured his thumb in a bunt attempt against Washington and was sidelined almost four weeks.17 In his second start after returning, he injured the same thumb while bunting and also suffered a leg injury in a collision at first base, and was scratched for three more weeks.18 Dietrich’s once promising season ended with a 5-8 record with a bloated 5.35 ERA in 109⅓ innings.

After the White Sox’ sixth-place finish in 1942, sportswriter Irving Vaughan of the Chicago Tribune opined ominously that “only a super-optimist would endeavor to paint a picture showing the Sox ready for what is coming in 1943.”19 Dietrich, who had won six of 17 decisions with the fourth-highest ERA in the league (4.89) in 160 innings the previous season, was named Opening Day starter. He lost his first three starts despite yielding just seven earned runs in 24 innings, then was hit on the right arm by a liner off the bat of Washington’s Rip Radcliff on May 9.20 Dietrich suffered no broken bones, but his arm was put in splints. Over the next seven weeks he made only four abbreviated starts before hurling a four-hit shutout on July 1 against Early Wynn and the Senators, completed in one hour and 39 minutes. Bullfrog finished the season in a flurry, winning all five of his decisions by complete game in September with a stellar 1.29 ERA in 56 innings. Included among his six starts were consecutive 10-inning outings (in the former of which he scored the winning, walk-off run after being hit by a pitch), as well as a seven-hit shut-out against New York in Yankee Stadium.21 In his hitherto best season in the big leagues, Dietrich set new personal bests in wins (12; he also lost 10), starts (26), and ERA (2.80 in 186⅔ innings) for the surprisingly competitive fourth-place White Sox (82-72).

In 1944 the White Sox conducted spring training for the second consecutive season in the southern Indiana spa town of French Lick, about 280 miles from Chicago. Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis had instituted travel restrictions and ordered all teams to conduct camp north of the Mason-Dixon Line and east of the Mississippi River in order to conserve resources for the war effort. (The St. Louis teams were excepted.) The White Sox and their NL brethren, the Cubs, shared a site at the French Lick Spring hotel, and battled cold, wet weather.22

While the White Sox lost defending AL batting champion shortstop Luke Appling and workhorse southpaw Eddie Smith to military service, the pitching staff remained relatively intact for the ’44 season. Dietrich, who had been given a 1-B classification (fit for limited service because of previous injury and his family),23 was joined by the top winner from ’43, Orval Grove, Johnny Humphries, and a highly touted 26-year-old rookie, southpaw Eddie Lopat. That group impressed Chicago beat writer Irving Vaughn, who boldly predicted that the club would win the AL pennant.24

After dropping his first two starts of the ’44 season, Dietrich finally won in exciting fashion. Described by Tribune writer Ed Burns as “the big man on offense and defense,” Dietrich held Cleveland to five hits, singled in the 10th, and subsequently tallied the walk-off run with two outs on a “brilliant sprint” from second base in a 3-2 victory.25 Not known for his hitting or running, Dietrich batted just .150 (94-for-627) in his career. For what seemed like the first time since his rookie season, Dietrich hurled an entire season without suffering a serious injury. To be sure, he still occasionally let his temperament get the best of him; he often argued with skipper Jimmy Dykes and bawled out teammates who muffed plays. Ed Burns described Dietrich as “high-strung” and “allergic to nagging”;26 however, the 34-year-old Bullfrog enjoyed a career year in 1944. Over a nine-week stretch from May 27 to August 3, he was one of the best twirlers in the league, completing eight of 17 starts, winning 12 of 17 decisions, and carving out a stellar 2.17 ERA in 124⅓ innings. On July 9 he was honored in his hometown after the first game of a doubleheader against the A’s at Shibe Park. Dietrich picked up the win (one run in six innings) and also war bonds and a travel bag, while friends and families made public tributes. Despite Vaughn’s optimistic prediction, the White Sox finished in seventh place as the offense sputtered, finishing last in batting average, home runs, and slugging percentage, and seventh in runs scored. In what proved to be Dietrich’s last full season in the majors, he set personal bests in practically every pitching category, including wins (16) starts (36), innings (246), and complete games (15) while posting a 3.62 ERA. He was also a hard-luck loser; in 16 of his league-leading 17 defeats (tied with Early Wynn), Chicago scored just 22 runs, including nine games of one run or less.

Dietrich was the object of fierce trading rumors in the offseason. Most reports had him going to the Cleveland Indians as part of a four- or six-player deal, but neither skipper Dykes nor player-manager Lou Boudreau could agree on what they considered an equitable transaction.27 Nonetheless, when Chicago opened spring training in Terre Haute, Indiana, about 180 miles south of the Windy City, Dietrich was nowhere to be found. [As Don Zminda has pointed out, the Cubs’ and White Sox’ two-year experiment conducting joint spring training in French Lick ended because of players and coaching staffs arguing about space, facilities, and even the golf course.28] Demanding a raise, Dietrich finally arrived in camp at the end of March after accepting a contract worth $9,500, a substantial $2,500 salary increase. But after his first start, Dietrich complained of soreness in his elbow. Irving Vaughn reported that an examination by team physician John Claridge determined that the 35-year-old hurler had bone chips in his elbow that required surgery.29 Despite optimistic predictions that the hurler would miss only three weeks, Dietrich made his next start two months later. In that dramatic return on June 18, Dietrich spun a four-hit shutout against Dizzy Trout and the Detroit Tigers, earning the 1-0 victory when Mike Tresh hit a one-out walk-off single. He tossed two more 1-0 shutouts in a three-start span in July, blanking Philadelphia on nine hits and hurling 11 frames against New York in Yankee Stadium, allowing seven hits and walking just one. The latter was the ninth and final time Dietrich pitched at least 10 innings in a game. Suffering from arm pain throughout the season, Dietrich was limited to 16 starts, finishing with a 7-10 record and 4.19 ERA in 122⅓ innings for the sixth-place White Sox.

Named Opening Day starter in 1946, Dietrich squared off against Bob Feller in a rematch from five years earlier, on April 16 at Comiskey Park. Dietrich “pitched with brilliance,” opined Ed Burns, striking out a career-high nine and allowing only six hits in a distance-going outing.30 However, Feller, who had tossed the first and (as of 2015) only no-hitter on Opening Day, was better, hurling a three-hitter and whiffing 10 in a 1-0 victory. Given some extra time between assignments, Dietrich was off to a good start before suffering a season-ending injury against Washington on June 25. A liner back to the mound by Cecil Travis hit Dietrich in the thumb, breaking it. According to the Tribune, Dietrich returned home to Philadelphia after initial x-rays and examinations; however, his relationship with Ted Lyons, who had replaced Dykes as skipper after 30 games, soon turned toxic. When Dietrich failed to report to Chicago for treatment, Lyons suspended him on August 15. “I acted in good faith when I left Chicago after the team physician told me I would have to wait for several weeks for additional x-rays,” said Dietrich, who also added defiantly, “I’ll just stay home even if I don’t get paid.”31 About a month later, Chicago gave Dietrich his unconditional release. He had posted a 3-3 record and robust 2.61 ERA in 62 innings.

Despite Dietrich’s age and an injury-prone career, the venerable Connie Mack signed the hurler. But it didn’t take long for the injury bug to reappear as a member of the A’s in ’47. According to The Sporting News, Dietrich tore a back muscle in spring training.32 After two relief outings, Dietrich made his first start on May 6 against the White Sox at Comiskey Park. Relying on guile and probably a desire for revenge, Dietrich tossed his 17th and final shutout, blanking his former team on five hits. Plagued by arm pain all season, Dietrich made only eight more starts, finishing with a 5-2 record, a 3.12 ERA and 40 walks 60⅔ innings. In his last victory of the season, as well as a big-league starting pitcher, Dietrich tossed a five-hitter to beat Chicago at Shibe Park.

The dean of AL hurlers in 1948, Dietrich tossed only 15⅓ innings before he was released on June 14, bringing an 18-year career in Organized Baseball to a conclusion (except for an abbreviated comeback attempt with Triple-A Oakland in 1950). He compiled a 108-128 record, started 253 of 366 appearances, and posted a 4.48 ERA in 2003⅔ innings as a big leaguer.

Dietrich settled into his post-playing career with his wife, Doris, his former high-school sweetheart, and their two children, Bill Jr. and Lynne. Save for his brief spell with Oakland, Dietrich had very little contact with major-league baseball after his playing days. He worked as a salesman for the Frankford-Unity grocery-store chain, retiring in 1957. “I’m through with baseball,” Dietrich said in 1952.33 According to Philadelphia sportswriter Harold Rosenthal, Dietrich was bitter because he had played on poor clubs.34 He discouraged his son from playing baseball, too. “I always said that if I caught him playing baseball, I’d break his arm … his pitching arm.”35 Despite his father’s disapproval, Bill Jr. became a stalwart pitcher at Frankford High School and signed with the New York Yankees in 1952. In seven years spent primarily in the low minors, Junior went 40-41. As a member of the Monroe (Louisiana) Sports in the Class-C Cotton States League, Bill joined his father on April 28, 1955, by tossing a no-hitter against the Greenville (Mississippi) Bucks.36

Dietrich died at the age of 68 on June 20, 1978, at his home in Philadelphia.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Dietrich’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Unattributed and undated article in Bill Dietrich’s Hall of Fame file.

2 “Philadelphia High School Baseball Recaps of Public School Title Games,” TedSilary.com; tedsilary.com/BASEPLtitlerecaps.htm.

3 “Dietrich to Pitch Against Black Sox,” Mount Carmel (Pennsylvania) Item, August 15, 1929: 4.

4 “Bill Dietrich Hangs Up No-Hit, No-Run Record Saturday,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, June 8, 1931: 12.

5 Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, July 8, 1932: 12.

6 Ibid.

7 Frank Reil, “Tigers, Hustling Team Under Cochrane, Look Good To Mack,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 6, 1934: 18.

8 The Sporting News, November 19, 1952: 5.

9 The Sporting News, August 29, 1935: 2.

10 The Sporting News, July 9, 1936: 1.

11 The Sporting News, June 5, 1941: 1.

12 The Sporting News, June 10, 1937: 2.

13 Associated Press, “Bill Dietrich Is On Retired List,” Shamokin (Pennsylvania) News-Dispatch, July 14, 1938: 10.

14 The Sporting News, June 5, 1941: 1.

15 The Sporting News, November 19, 1952: 5.

16 “Bill Dietrich To Pitch Today in Boston Final,” Chicago Tribune, July 24, 1941: 17.

17 “Chicago Fans Give Watch To Connie Mack,” Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1941: 31.

18 “Bill Dietrich To Pitch Today in Boston Final,” Chicago Tribune, July 24, 1941: 17.

19 Irving Vaughan, “White Sox Lead with Dietrich; Play St. Louis,” Chicago Tribune, April 21, 1943: 31.

20 Judson Bailey, “Lively Ball Brings Lively Disputes to Big Leagues Sunday,” Dixon (Illinois) Evening Telegraph, May 10, 1943: 6.

21 Irving Vaughan, “Sox Win, 3-2, Over Browns in 10 Innings,” Chicago Tribune, September 18, 1943: A1.

22 “Sports Flashback: White Sox and Cubs spring training in French Lick,” Chicago Tribune, February 20, 2015. Chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/ct-flashback-cubs-sox-spring-training-spt-0222-20150220-story.html.

23 “Bill Dietrich Accepted For Limited Service,” Alton (Illinois) Telegraph, March 3, 1944: 16.

24 Irving Vaughan, “Sox Rated as Team to Beat for the A.L. Crown,” Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1944: A1.

25 Ed Burns, “Cubs Face Reds; Sox Win in 10th,” Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1944: 25.

26 Ed Burns, “Bill Dietrich Yields 7 Hits in 9-5 Triumph,” Chicago Tribune, September 9, 1944: 19.

27 Ed Burns, “Sox and Indians Pilots Weigh 6 Player Deal,” Chicago Tribune, December 7, 1944: 31.

28 Don Zminda, “The White Sox in Wartime,” in Who’s On First. Replacement Players in World War II, eds. Mark Z. Aaron and Bill Nowlin (Phoenix, Arizona: Society for American Baseball Research, 2015), 221.

29 Irving Vaughan, “Dietrich Lost to White Sox for Three Weeks,” Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1945: 25.

30 Ed Burns, “Cubs Win, 4-3; Indians, Feller Whip Sox, 1-0,” Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1946: 25.

31 “Suspension Irks Dietrich,” Chicago Tribune, August 17, 1946: 17.

32 The Sporting News, April 16, 1947: 18.

33 The Sporting News, November 19, 1952: 5.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 Associated Press, “No-hit Game Pitched by Bill Dietrich, Jr.,” Terre Haute (Indiana) Tribune, April 29, 1955: 2.

Full Name

William John Dietrich

Born

March 29, 1910 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

June 20, 1978 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.