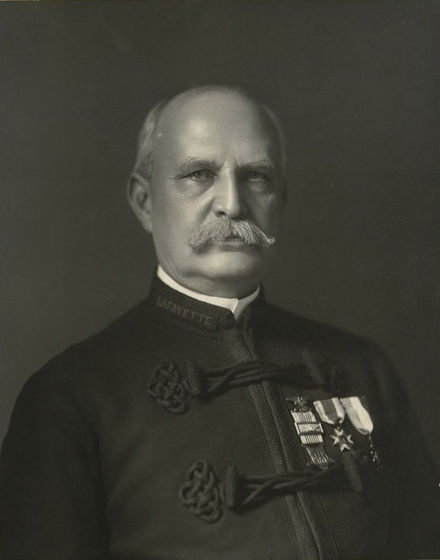

A.G. Mills

Baseball pioneer Abraham Gilbert Mills is remembered-if at all-today for heading the “Mills Commission” which concluded that the game of baseball was invented in America by Civil War General Abner Doubleday. However, this actually represents a very small piece of Mills’ fascinating life.

Baseball pioneer Abraham Gilbert Mills is remembered-if at all-today for heading the “Mills Commission” which concluded that the game of baseball was invented in America by Civil War General Abner Doubleday. However, this actually represents a very small piece of Mills’ fascinating life.

Born March 12, 1844, in New York City, Mills lived there until the outbreak of the Civil War when he enlisted as a private with the 5th New York Volunteers in 1862. Surprisingly, the war did not curtail his baseball playing opportunities. In writing about his war years, Mills remembered packing his bat and ball with his field equipment because he found as much use for them as for his sidearms. In fact, he played in a famous Christmas Day 1862 baseball game at Hilton Head, South Carolina, between the 165th New York Volunteer Infantry Duryea’s Zouaves and a handpicked nine from other Union army regiments. According to reports, 40,000 soldiers witnessed the game.

Mills was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in 1864 and honorably discharged in 1865. His often referred to nickname “Colonel” was simply an honorary title.

After the war, Mills relocated to Washington, D.C., to study law at Columbian Law School (now George Washington University). While in Washington he also became president of (and occasional player for) the Olympic Base Ball Club, and tried unsuccessfully to recruit a young pitcher, Albert Spading, who would later, often with the help of Mills, become one of the most innovative and influential sports figures of the 19th century.

In 1872 Mills married Mary Chester Steele. Their marriage would produce three daughters. After being admitted to the bar, Mills moved to Chicago. It was there, in 1876, that his career took an unexpected turn. National League (NL) baseball teams at that time would freely sign players who were already under contract with non-league teams. Often, several teammates would be taken together, and the depleted non-league team would have no choice but to disband. Mills wrote a scathing newspaper article denouncing this practice and outlining a plan to prevent the raiding of non-league teams. This article caught the eye of NL president William Hulbert, who asked Mills for his help in formulating it into an official document. The plan, completed in 1877, was known as the League Alliance. The NL was very impressed with Mills’ work and kept him on as an advisor. Shortly after Hulbert’s death in 1882 the league unanimously elected him president.

Mills’ first goal as president was to prevent players from routinely jumping from one professional league to the next (often in mid-season) in order to obtain a higher salary. In 1883 at the Hotel Victoria in New York, Mills assembled representatives from the three main professional leagues (the National League, American Association, and Northwestern League) in what was dubbed the “Harmony Conference.” Before the afternoon was out, the men formed the “National Agreement of Professional Base Ball Clubs” (sometimes referred to as the “Tripartite Agreement”), which stated that every league team would be able to keep 11 players at the conclusion of a season. These “reserved” players would have no choice but to play for their current team during the next season. This agreement was extremely unpopular with the players, who now had no control over where they played or how much money they made.

Almost immediately the players struck back. Within six months of the formation of the National Agreement, a new league-the Union Association (UA)-was formed to begin play in the 1884 season. The UA’s big attraction was that it did not recognize the reserve rule or salary limitations. Despite Mills’ threats of permanent expulsion and heavy fines, many players defected to the new league. The result was a chaotic 1884 season. Some cities had as many as three professional teams playing within a few miles of each other fighting for a small fan base. Due to this tug-of-war, attendance was low in every league and many teams folded during the season-some after only a handful of games.

After incurring severe financial loss and barely surviving the season, the UA disbanded. UA players naturally wanted to re-join the NL, but Mills stuck to his guns and refused to allow the “secessionists” back in, saying he was “never more earnest…that these players should never play with any club connected with the National Agreement” (Pietrusza

85).

The league, looking to increase its attendance and financial stability, was more forgiving, and despite Mills’ protests voted to allow the former UA players back in for the 1885 season. The final straw for Mills came when the league voted to allow Henry Lucas-none other than the founder of the Union Association-into the league as the owner of a new St. Louis franchise. An angry and humiliated Mills stepped down as league president in November 1884.

Time eventually healed his wounds and hard feelings, and although no longer officially employed by the league, Mills was often consulted by baseball officials on league matters. In fact, in 1890 he was involved in a matter he was quite familiar with: players jumping to a newly formed league-the new Players League. When it was rumored (falsely as it turned out) that the Players League was planning an attractive employment offer to entice Mills to switch sides, a panicked Spalding quickly created the position of National League chief arbitrator for Mills, who although flattered by the offer, declined to accept it.

In 1888 Spalding took a group of star players around the world to promote the game of baseball. They visited such far away places as Australia, Italy, and England, and even played a game in the shadow of the Great Pyramids of Egypt. Upon their return in April 1889, Mills was asked to be the master of ceremonies at a dinner honoring Spalding and the players. The dinner, held at Delmonico’s restaurant in New York, was attended by an interesting mix of 300 guests including Mark Twain, Theodore Roosevelt, local politicians, baseball officials, Yale undergraduates, and popular members of the New York Stock Exchange.

The main theme of the speeches given at the dinner was how baseball was purely American, invented by Americans, and now had been taught to the rest of the world by Americans. It was not, as many believed, evolved from the British game of rounders. Several times during the evening rousing chants of “No rounders! No rounders!” were bellowed. This show of patriotism intrigued Spalding. For many years he had a friendly ongoing debate with fellow baseball pioneer Henry Chadwick about the origins of baseball. Spalding insisted it was invented in the United States, while the British-born Chadwick maintained it evolved from rounders.

The debate came to a head in 1903 when Chadwick published a widely read article tracing baseball’s evolution from rounders. Spalding almost immediately published an article disputing this claim. He made a suggestion to Chadwick, “Let us appoint a commission to search everywhere that it is possible and thus learn the real facts concerning the origin and development of the game. I will abide by such a commission’s findings regardless” (Spalding 11). Chadwick agreed with Spalding and in 1905 a commission was formed.

Seven prominent men made up the “Mills Commission”: Chairman Abraham G. Mills; Morgan G. Bulkeley, the NL’s first president in 1876; Arthur P. Gorman, a former player and ex-president of the Washington Base Ball Club; Nicholas E. Young, the first secretary and fifth president (replacing Mills) of the NL; Alfred J. Reach and George Wright, well known sporting goods distributors and two of the most famous players of their day; and James E. Sullivan, president of the Amateur Athletic Union.

The commission, through a series of nationally distributed articles in newspapers and sporting publications, asked all Americans who had any knowledge about the formation of the game of baseball to come forward. While passing through Akron, Ohio, on April 3, 1905, a 71-year-old mining engineer from Denver named Abner Graves happened to pick up a copy of the Akron Beacon Journal and read with interest one such article written by Albert Spalding. He went back to his hotel room and typed a letter to the Beacon Journal on his personal stationery. Graves’ letter ran the very next day under the headline “Abner Doubleday Invented Base Ball.”

According to Graves, Doubleday improved the local version of Town Ball being played between pupils of the Otsego Academy and Green’s Select School in Cooperstown, New York. This took place “either the spring prior to or following the ‘Log Cabin and Hard Cider’ campaign of General William H. Harrison for the presidency” (Tofel A20). Graves claimed to be present when Doubleday, drawing on a patch of dirt with a stick, outlined defensive positions on a diamond shaped baseball field. He also claimed to witness Doubleday draw this diagram on paper along with a crude memorandum of the rules for his new game that he named “Base Ball.”

Spalding, Mills, and the rest of the committee were thrilled when they received a copy of the Beacon Journal article. This was exactly what they were looking for. Not only was Doubleday an American, but he was a heroic General in the Civil War. In addition, quaint, picturesque Cooperstown was the absolute perfect setting to represent the country.

The Mills Commission did not investigate the Graves claim. Nobody in the committee ever met or corresponded with Graves. Many glaring facts were overlooked: Graves was only 5 years old at the time of baseball’s “invention.” Doubleday was away at West Point and never set foot in Cooperstown in 1839. Mills himself was friends with Doubleday for over 30 years-so close he was chosen to command the military escort which served as Doubleday’s guard of honor when his body lay in state in 1893-yet never previously mentioned Doubleday’s role in the invention of baseball.

Despite all of the unanswered questions, Mills, on December 30, 1907, drafted an eight- paragraph letter addressed to committee member Sullivan declaring, “the first scheme for playing it, according to the best evidence obtainable to date, was devised by Abner Doubleday at Cooperstown, N.Y. in 1839” (Levine 114). Graves was never mentioned by name, and his article was referred to as “a circumstantial statement by a reputable gentleman” (Levine 114).

Over the years the lightly worded memo took on a life of its own, eventually becoming known as the “Mills Commission Report.” It would remain the final say on the origins of baseball for over half a century until several historians started to question it. It is now widely believed Chadwick was correct and baseball had in fact evolved from the game of rounders. Chadwick himself was amused at the committee’s findings. In a note to Mills he commented that “your decision in the case of Chadwick vs. Spalding…is a masterly piece of special pleading which lets my dear old friend Albert escape a bad defeat”

(Levine 115).

Mills himself had some doubts as to the validity of the commission report. At the National League’s 50th anniversary dinner in 1926 a reporter asked him what conclusive evidence he had for Cooperstown as baseball’s birthplace. Mills answered, “None at all, as far as the actual origin of baseball is concerned. The committee reported that the first baseball diamond was laid out in Cooperstown. They were honorable men and their decision was unanimous. I submit to you gentlemen, that if our search had been for a typical American village, a village that could best stand as a counterpart of all villages where baseball might have been originated and developed-Cooperstown would best fit the bill” (Tofel A20).

The work done for the commission was Mills’ last major role in professional baseball. He had long been associated with the Hale Elevator Company of Chicago. When one of their agents-the Otis Elevator Company of New York-was organized in 1898, he became Otis’ Vice President in charge of sales, a position he held until his death.

Mills and Spalding remained lifelong friends. When Spalding launched what turned out to be an unsuccessful campaign to become U.S. Senator from California in 1910, one of the first people he contacted was Mills, writing, “Publicity and lots of it is my only chance,” and asking him “for a word…with a little baseball twist” (Levine 140). Mills complied, writing a glowing newspaper article describing Spalding in part as “a man in the prime of his life, who, beginning as a country boy, has solely by square-dealing and honest effort, built up a business that extends the world over, and who therefore is just the man to further the trade interests of their state” (Levine 141).

In his later years amateur athletics became Mills’ new passion. He became the director and president of the New York Athletic Club, and in 1921 wrote the American Olympic Association constitution. At the time of his death on August 26, 1929, in Falmouth, Massachusetts, he was president of the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks, and was involved in planning the 1932 Winter Olympics.

Spalding summed up Mills’ career best when he wrote that his friend was “an executive of sterling endowments in the way of administering affairs and managing men” (Spalding 244).

Sources

Alvarez, Mark. The Old Ball Game. Alexandria, Virginia: Redefinition Books, 1990.

“Bismarck of Baseball.” The Otis Elevator Company Bulletin. April-May 1949.

Goldstein, Warren. Playing for Keeps. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989.

Husman, John R. “Mills, Abraham Gilbert ‘The Bismarck of Baseball.’” David L. Porter, ed. Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Leitner, Irving A. Baseball: Diamond in the Rough. New York: Abelard-Schuman, 1972.

Levine, Peter. A. G. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball. New York and London: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Mallinson, James. “Abraham Gilbert Mills.” Frederick Ivor-Campbell, Robert L. Tiemann, and Mark Rucker, eds. Baseball’s First Stars. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996,

Nemec, David. The Beer and Whisky League: The Illustrated History of the American Association-Baseball’s Renegade Major League. New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994.

Peterson, Harold. The Man Who Invented Baseball. New York: Scribner, 1969.

Pietrusza, David. Major Leagues. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1991.

Schleis, Paula. “Baseball Myth Born in Akron.” Akron Beacon Journal. July 1, 2002.

Seymour, Harold. Baseball. 3 vols. New York and London: Oxford University Press,

1960.

Spalding, Albert G. America’s National Game. New York: American Sports

Publishing Company, 1911.

_____. Spalding’s Baseball Guide. A. G. Spalding & Bros., 1903.

Sullivan, Dean A., ed. Early Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, 1825-1908. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

Tofel, Richard J. “The Innocuous Conspiracy of Baseball’s Birth.” Wall Street Journal. July 19, 2001. A20.

Voight, David Quentin. American Baseball. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1983.

Full Name

Abraham Gilbert Mills

Born

March 12, 1844 at New York, NY (US)

Died

August 26, 1929 at Falmouth, MA (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.