Baseball in the Middle of Nowhere: The Unique Story of Herbert Kokernot and the Alpine Cowboys

This article was written by C. Paul Rogers III

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Texas and Beyond (2025)

Sponsor Herbert L. Kokernot Jr. and manager Tom Chandler view the Alpine Cowboys practice at Kokernot Field in 1956. (Courtesy of Rick Herrscher)

Thanks to a successful, quiet, unassuming, and very generous rancher named Herbert Kokernot, the most remote part of the great state of Texas, sometimes referred to as Far West Texas, has a rich baseball history. Alpine, Texas sits about 25 miles southeast of the Davis Mountains and about 80 miles north of Big Bend National Park. It’s the land of cactus, desert willows, mule deer and javelinas, and, surprisingly enough, baseball.

Alpine has about 6,000 residents with the nearest commercial airport about three hours away, whether one chooses the Midland-Odessa Airport or El Paso. It is the seat of Brewster County, the largest by far of Texas’s 254 counties with almost half as many square miles (6,169) as people (about 9,500). Marfa, better known because of the mysterious Marfa Lights and as an art haven, 25 miles to the west, has all of 1,600 people and is the county seat of neighboring Presidio County. Fort Davis, population 855 and the county seat of Jeff Davis County, lies 25 miles to the northwest.

Baseball had been played in Alpine and the Big Bend area since the late nineteenth century with the soldiers at Fort Davis squaring off against cowboys from local ranches, especially on the Fourth of July. By the turn of the century, Alpine had a town team which played against teams from Fort Stockton, Marfa, Marathon, Fort Davis, Pecos, and Sanderson. With the arrival of the Orient Railroad in Brewster County around 1910, the local club became known as the Orient Team for a few years. Later they were called the Alpine Blues, and then the Vaqueros.1

Around 1945 a man named C. West, reputed to be a former big-league pitcher, moved to Alpine, opened the Texas Cafe and organized a local baseball team called the Alpine Cats. Fitted with new uniforms, the Cats won 11 of 12 games and attracted the attention of Herbert J. Kokernot Jr. Generally known as “Mr. Herbert,” he was the wealthy scion of the sprawling Kokernot O6 (pronounced “oh six”) Ranch, which covered some 320,000 acres in Brewster, Jeff Davis, and Pecos Counties. Kokernot had played baseball in high school at the San Marcos Baptist Academy and later as a .300 hitting infielder for the Alpine Independents town team.2 To say he had a passion for the game would be an understatement. Before the 1946 season began, Kokernot had donated land for a ballpark for the Cats and he oversaw the construction of a somewhat makeshift ballpark with wooden planks, chicken wire, a corrugated tin roof, and the O6 brand on the wooden fences.3

Kokernot was soon all in and bought the Cats that summer, renaming the team the Cowboys and outfitting them with new uniforms. Herbert Kokernot Sr. had long ago turned over the running of the O6 Ranch to his son and lived in the more civilized San Antonio. On the father’s annual visit to Alpine that summer, Herbert Jr. told his dad—who cared little for baseball—about his purchase of the ballclub and drove him by the ballpark. Days later, when Herbert Sr. was about to board a train back to San Antonio, he turned and looked his boy in the eye and said, “Son, if you’re going to put the O6 brand on something, do that thing right.” He then climbed on the train and left.4

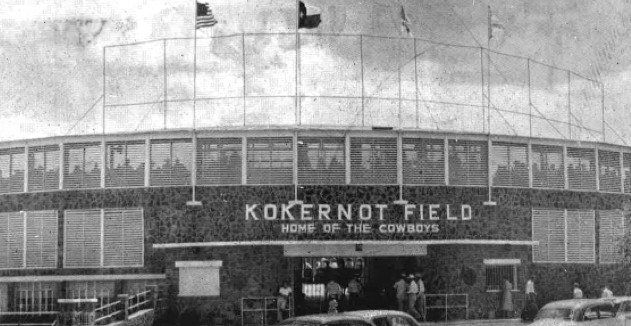

That was all the encouragement Herbert Jr. needed. He decided to start over with a new ballpark and picked a spot just west of the Sul Ross State College campus. Herbert Jr. spared no expense, spending an estimated $1.25 million on Kokernot Field, which opened in May 1947. The ballpark had a completely roofed, concrete, 1,200-seat grandstand, with wooden seats with individual arm and was rests, faced with local reddish-brown stone. On a visit to Georgia, Kokernot had admired the state’s rich, red clay, and so ordered enough for the infield and had it shipped to Alpine by boxcar. Real Bermuda grass covered the playing field. The stone outfield wall was adorned with the O6 brand, with center field a daunting 430 feet from the plate.

Mr. Herbert also paid attention to detail, commissioning decorative iron baseballs from a San Antonio metalworks and having red stitches painted on them. They were hung in clusters over the stone entrance gates.5 A rose garden led to the concession stand which sported a red Spanish tile roof and was framed by pewter bats.6 Gardeners planted flowers and ivy outside the park and the outfield walls were painted bright blue, making Kokernot Field appear to be a baseball oasis in the middle of its arid surroundings.7 One writer describe the decor as “Early Cooperstown.”8

Kokernot outfitted the team with new uniforms with the O6 brand on the sleeve and soon sought to bring in talented semiprofessional players from throughout the state, rather than rely on those available locally. Soon the team became mostly college players, including a number from Sul Ross. His goal was to qualify for the National Baseball Congress Tournament in Wichita, Kansas, which annually attracted the best semiprofessional teams in the country. In 1947, the Cowboys won 20 of 26 games and also won the Sixth Annual Southwestern Semiprofessional Baseball Tournament in El Paso, thus qualifying for Wichita. Mr. Herbert chartered a Pullman for the team to travel in style. After four wins in the Wichita tournament, they lost to the Florida Railroaders in their first bid for a national championship.9

Tom Chandler of Baylor was a stalwart on the first Cowboys teams. He developed a close relationship with Kokernot and in 1952 began a very successful run as coach of the team.10 Together they recruited college stars including Adrian Burk and Larry Isbell of Baylor, and Yale Lary of Texas A&M, later an all-pro defensive back with the Detroit Lions. Later in the decade, future major leaguers Carl Warwick of TCU and Rick Herrscher of SMU played for the Cowboys, as well as other Southwest Conference stars like SMU’s Tommy Bowers and Larry Click and Jerry Mallett of Baylor.

Sul Ross had a strong NAIA baseball program, winning the national championship in 1957, held at Kokernot Field, and many of their top players suited up for the Cowboys in the summer, including Norm Cash, who went on to a stellar major league career with the Detroit Tigers.11

Kokernot and Chandler developed nationwide baseball contacts and in 1957 were called by Milwaukee Braves scout Gil English about a high school farm boy from North Carolina’s Tobacco Road area who threw very hard but was a raw talent. The Cowboys had never had a high schooler, but were convinced to give this one, whose name was Gaylord Perry, a shot. Perry, however, had flunked his English class that spring, and had to somehow make it up to be eligible for his senior year. The team arranged for Perry to take a correspondence course from Texas Tech to make up the course.12

Manager Chandler initially told Perry not to throw too hard in response to Perry’s concern that he might hit someone because he was so wild.13 In a game against the Sinton Oilers, Perry was getting knocked around until he asked Chandler, “Can I just throw harder?” Chandler said yes, and Perry was pretty much untouchable for the rest of the summer.14

Perry’s off-the-field problem, passing English, persisted. Willowdean Chandler, Tom’s wife, was Perry’s correspondence course tutor, but the lack of a workbook hindered his progress in the course. Mrs. Chandler took to filling in the answers to his assignments—careful not to answer them all correctly—and then sending them in. The final exam posed a problem, however, because it had to be taken in front of a high school principal. It turned out that Chuck Ellis, the principal of Marathon High School, 25 miles east of Alpine, loved the Cowboys baseball team, so he and his wife and Chandler and Willowdean took the exam for Perry while in the car driving to a road game.15

Under NCAA rules, college athletes were not allowed to be paid for playing their sport in the summer, so Kokernot hired the players for $400 a month to work on his ranch, while they played baseball for the Cowboys ostensibly for free. One of the typical jobs was killing jackrabbits, which were a plague on the ranch. The players used old Jeeps and drove through the prairie armed with .22s and even pistols, chasing the rabbits down until the critters tired and stopped.16

Kokernot Field (Courtesy of Rick Herrscher)

In 1955, the big local event was the filming of the movie Giant in Marfa, 25 miles away. The movie starred Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, and James Dean, and included a 19-year-old Dennis Hopper. During the shooting, it was arranged for the Alpine team to visit the famous house set and meet the actors. Doyle Stout, one of pitchers for the Cowboys, had a conversation with James Dean in which Dean asked. “What do you guys do here for excitement?” Stout replied that hunting jackrabbits from the hood of his car, armed with 35-inch baseball bats, was one of his favorite pastimes. Dean thought that sounded great, and a couple of days later joined some of the ballplayers, “yelling, cursing, and swinging and having a great time, although he didn’t hit a lot of rabbits.”17

Mr. Herbert was nothing if not generous with his players and annually donated bushels of scholarships to enable students to attend Sul Ross. He often rewarded players for home runs or well-pitched games with a $50 or $100 bill and hosted frequent barbecues at his ranch for the entire team. In the early years of the Cowboys, the players stayed at the Holland Hotel in downtown Alpine and just signed for their meals; Mr. Herbert took care of all their food and lodging. However, after Larry Isbell, a high-profile player from Baylor, abused the practice by buying a new set of tires for his car and a trolling boat on Kokernot’s credit, the players were relegated to the dorms at Sul Ross.18

Kokernot, ever the baseball enthusiast, also sometimes enlisted major league teams to play spring training exhibition games in Alpine, beginning with a Cubs-Browns tilt in 1949, played before a sellout crowd.19 In 1951, Satchel Paige and the St. Louis Browns took on the Chicago White Sox as a reported 6,000 fans from all over the area crammed into Kokernot Field. Mr. Herbert announced that he would pay $100 to the player on each team who got the most hits, plus other cash prizes for most total bases, strikeouts, and assists.20 Paige, who pitched one inning of the game, remarked to Kokernot before the game how much he liked his white Stetson. By the time of the postgame barbeque at the O6 ranch, Kokernot had arranged to pass out white cowboy hats to the entire Browns team.21

In 1953 the Browns and Cubs again played at Kokernot Field as Mr. Herbert handed out $1,900 in “bonuses” for top performances, including $500 to the Browns for the winning the game.22 In early April 1956, another jammed house saw Ernie Banks blast two home runs over the left-field fence during a Cubs-Orioles exhibition game that the Cubs won 16-4.23 In the third inning, an Air Force fighter jet, probably stationed in Del Rio, zoomed over the field at about 500 feet, causing some, like Cubs pitcher Russ Meyer and umpire Stan Landes, to dive for cover.24

Also in 1953, Kokernot arranged for the Brooke Army Medical Center team to play a series in Alpine, since the Brooke team featured major leaguers Don Newcombe and Bob Turley, who were both in the service. Mr. Hebert promised to pay Newcombe $1,000 an inning pitched and Newcombe remembered, “I don’t care if my arm was sore, I pitched five innings.”

Newcombe never forgot Mr. Herbert’s generosity and left tickets for him for Game Seven of the 1955 World Series.25 Of course, Johnny Podres, who had just turned 22, famously pitched the Brooklyn Dodgers to their first World Championship in that game with a 2-0 shutout over the New York Yankees. Afterwards, Kokernot managed to push his way up to Podres in the Dodgers clubhouse. Mr. Herbert told Podres he wanted him to come to Alpine to pitch sometime, and when he whispered a figure in Podres’ ear, he got the lefty’s attention.26

The opportunity probably came sooner than expected. In 1956, the Cowboys fielded a very strong team behind such stalwarts (and future big leaguers) as Rick Herrscher of SMU and Jacke Davis of Baylor and qualified for the National Baseball Congress Tournament in Wichita. Teams often used ringers in Wichita and the Cowboys made a real splash by adding Podres—who was then in the Navy—and future National League Rookie of the Year Jack Sanford, who was also in the service. Podres flew to Wichita and struck out seven in four innings in an eventual 23-2 Cowboys victory, while also going 4-for-5 at the plate.27 Podres later recalled that Mr. Herbert paid him $1,000 to pitch, plus $100 a strikeout.28

Jack Sanford also pitched and won a game for the Cowboys in Wichita, but protests ensued, and the military leaves of both players were canceled. The Cowboys ended up finishing third in the tournament.29

For years Kokernot planned to add lights to the field, so people with weekday jobs could attend games, and he visited ballparks around the country to find the best lighting available. He was ready to have them installed before the 1958 season, telling his contractor, “I want lights better than Yankee Stadium.” When the lights were switched on before the Cowboys’ first game of 1958, a tilt against the Dyess Air Force Base Sonics, the crowd gasped and cheered as 435,000 watts bathed the field.30

Before the game, Mr. Herbert visited the Cowboys’ dugout and offered a $100 bill to the first player to hit a home run under the lights. The result was that everyone swung from the heels, with few making good contact and no one hitting a homer. In fact, it took several games before Gene Leek of the University of Arizona finally sent one out of the park.31

Aerial view of Kokernot Field in the early 1950s. (Courtesy of Rick Herrscher)

Those ‘58 Cowboys were a juggernaut, led by future major league pitcher Joe Horlen and his shortstop brother, Bill, from San Antonio. They finished the summer with a 45-5 record—with Horlen going 12-1—and again qualifying for the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita. There the team advanced to the championship game, but fell to the Drain, Oregon, Black Sox in a nail-biting final, 8-7, to finish second.32

In 1959, with it becoming more difficult for the Cowboys to find semipro and military teams in the region to play, Kokernot, perhaps against his better instincts, entered into a working agreement with the Boston Red Sox to field a team in the Class D Sophomore League. Mr. Herbert insisted that the team be called the Cowboys and refused to permit the typical outfield fence advertising signs favored by minor league teams.33 Alpine was the smallest city in affiliated baseball and literally half the town, 2.500 people, turned out for the opener, an 18-1 shellacking of San Angelo.34 It was a precursor of the season to come as the team won 88 games against just 34 losses. Led by Don Schwall, who won 23 games, and Chuck Schilling, who batted .340, the Cowboys at one juncture won 15 games in a row and topped their four-team division by a whopping 34 games. Just two years later with the Boston Red Sox, Schwall would be named American League Rookie of the Year while Schilling would place fourth in the balloting.35

The 1960 club, led by future American League All-Star Jim Fregosi—who later called Kokernot Field the best ballpark he ever played in36—won the regular season by six games with a 76-52 record before losing the playoffs to Hobbs, two games to one. Mel Parnell, the former Red Sox ace, was sent to manage the ‘61 club, but before the season was out, Boston announced it would not renew its working agreement. That was fine with Mr. Herbert, who lamented how the Red Sox treated the players, buying and selling them like cattle.37

Kokernot Field then became the home park to Sul Ross, and when Sul Ross dropped baseball in 1968, to the Alpine High School Fighting Bucks. But the field gradually fell into disrepair until Sul Ross restarted its baseball program in 1984. The school leased the park and put $150,000 into its refurbishment.38 Mr. Herbert consented to throw out the first pitch for the Lobos’ first game in 16 years. Kokernot passed away in 1987, at age 87, leaving behind a beautiful ballpark, plus a legacy of generosity, kindness, and love for the game of baseball.

In 2009, professional baseball returned to Alpine and Kokernot Field for the first time in 48 years with the debut of the Big Bend Cowboys of the independent Continental League. Two years later the team reorganized as a non-profit and as the Alpine Cowboys became charter members of the far-flung independent Pecos League.39 There they have thrived through 2024, winning their division championship eight times and the league championship three times. In 2024, the Cowboys had a truly incredible season, winning 45 games and losing only four before sweeping through the league playoffs with six more wins against a single loss.40

Mr. Herbert’s paean to the great game in Far West Texas thus lives on.

C. PAUL ROGERS III is president of the Ernie Banks-Bobby Bragan (Dallas-Fort Worth) SABR Chapter and the co-author of four baseball books, including The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant written with his boyhood hero Robin Roberts, and Lucky Me: My 65 Years in Baseball authored with Eddie Robinson. He is also co-editor of SABR team histories of the 1951 New York Giants and the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies as well as a frequent contributor to the SABR bio and games projects. His real job is as a law professor at SMU where he was dean of the law school for nine years and has served as the university’s faculty athletic representative for 38 years.

Notes

1. Betty L. Dillard and Karen L. Green, “Beeves and Baseball: The Story of the Alpine Cowboys,” The Journal of Big Bend Studies (Vol. 11, 1999): 172.

2. Dillard and Green, 173-75.

3. Nicolas Dawidoff, “The Best Little Ballpark in Texas (Or Anywhere Else),” Sports Illustrated (July 31, 1989).

4. Dick Sheffield, “A Field of West Texas Dreams,” Boston Sunday Globe, March 21, 1999: A12; Dawidoff.

5. Dillard and Green, 177.

6. William M. Adler, “Just Imagine: the Kokernot Yankees,” New York Daily News, February 20, 2000: 1245.

7. Dillard and Green, 177.

8. Ray Buck, “Love Field,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 29, 2003: 48.

9. In 1948 the Cowboys made it back to Wichita, only to exit the tournament early. When Mr. Herbert learned that the team from Glen Ridge, New Jersey was out of funds and stranded, he charitably offered them the hotel rooms being vacated by Alpine and paid their expenses for the balance of the tournament. Glen Ridge, dubbed the New Jersey Cowboys, finished the tournament in fourth place. Dillard and Green, 178; Buck, 48.

10. Tom Chandler went on the become the highly successful baseball coach at Texas A&M University, where in 26 years, he won five Southwest Conference championships and was named Coach of the Year seven times. He was elected to the Texas A&M Athletic Hall of Fame in 1991.

11. Dawidoff.

12. David Vaught, Spitter—Baseball’s Notorious Gaylord Perry (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2023): 69.

13. DJ Stout, The Amazing Tale of Mr. Herbert and His Fabulous Alpine Cowboys Baseball Club (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010): 147.

14. Sheffield, A12.

15. Stout, 147; Vaught, 70-71.

16. Robert L. McCartha, Texas Heat, Chicago Fire: The Remarkable Life of Joe Horlen(North Charleston, SC, 2017): 57-58.

17. Stout, 159.

18. Interview with Rick Herrscher, January 21, 2025; Sheffield, A12.

19. The Cubs won 7-6 as Roy Smalley hit a home run for the Cubs and Al Zarilla and Gerry Priddy hit for the circuit for the Browns. L.A. McMaster, “Browns Find Baseball In Alpine, Tex., Costs Plenty to Kokernots,” St Louis Post-Dispatch, April 1, 1949: 36.

20. The White Sox won 3-1 with two runs in the bottom of the eighth to break a 1-1 tie. “3,000 See Chisox Victory At Alpine,” San Angelo Standard-Times, March 31, 1951: 4.

21. Dawidoff; Dillard and Green, 185.

22. The final score was 9-4 behind 16 hits by the Browns. L.A. McMaster, “Browns Collect 16 Hits, A 9-4 Victory and $1330 In Big Payoff With Cubs,” St Louis Post-Dispatch, April 3, 1953: 33.

23. Chuck Whitlock, “Chicago Cubs Slaughter Baltimore Orioles, 16-4,” El Paso Times, April 6,1956: 34.

24. “Cubs Rout Orioles, 16-4, At Alpine’s Kokernot Field,” San Angelo Standard-Times, April 6, 1956: 19; Stout, 175.

25. Sheffield, A12.

26. Dawidoff.

27. Stout, 179.

28. Dawidoff.

29. Stout, 179.

30. Stout, 202.

31. Stout, 213.

32. McCartha, 59-60.

33. “Kokernot To Skip Fence Signs,” El Paso Times, January 25, 1959: 34.

34. Dawidoff.

35. In other words, both would jump from Class D to starring roles in the Major Leagues in just two years.

36. Dawidoff.

37. Stout, 235. Seventeen year-old Dalton Jones, who played nine years in the big leagues, was on the ‘61 Cowboys, who finished 62-63, good for fourth place in the six team Sophomore League.

38. Mark Rogers, “Field of Dreams,” Odessa American, October 16, 1989: 9; Buck, 48.

39. Bill Rogan, Life Ain’t the Same in the Pecos League (Self-published, 2020).