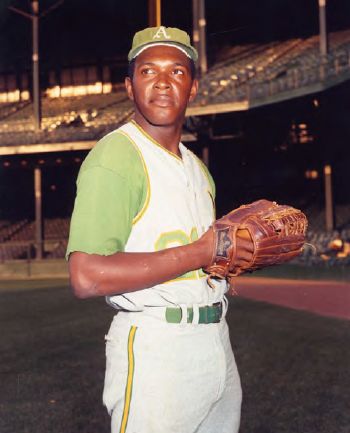

Vida Blue, His Greatest Year

This article was written by Glenn Dickey

This article was published in Northern California Baseball History (SABR 28, 1998)

There are good years and there are great years and there are years which simply defy description, which is the kind of year that Vida Blue had in 1971 as the Oakland A’s won their first American League West division championship.

There are good years and there are great years and there are years which simply defy description, which is the kind of year that Vida Blue had in 1971 as the Oakland A’s won their first American League West division championship.

Great things had been expected of Vida from the time he signed after being a great all-round athlete in high school, a great pitcher and a quarterback who had been offered college scholarships: his high school football coach, in fact, negotiated his contract with the A’s. In 1970, he had a 12-3 record with a 2.08 ERA in Triple-A ball at Iowa. Brought up in September, he was 2-0 and one of those two wins was a no-hitter.

But nobody, including Blue, quite expected what would happen in 1971.

“I was in the zone all year,” Vida remembered. “It was tremendous, all the attention, the magazine covers, the interviews. I loved it. I just had great confidence that nobody would be able to hit me.”

For the most part, he was right. He finished at 24-8 with an incredible 1.82 ERA, striking out 312 batters in 301 innings, pitching eight shutouts, allowing only 209 hits, an average of less than seven hits per nine innings. He won both the Cy Young and Most Valuable Player awards.

But mere statistics don’t tell the whole story. Vida was the big story in baseball that year, a young, handsome, exuberant man with a great talent and a zest for life. Game after game, he would flash that great fastball past hitters, talk exuberantly with reporters after the game, and sign autographs as long as there were fans asking for them.

Vida has always had a close relationship with fans; even now, he says, he’s thrilled when people come up to him to talk about his career. In that magical year of 1971, there were more fans in the autograph lines and in the stands than any other player saw. When the final attendance figures were in, an enterprising writer, Ron Bergman, who was following the As for the Oakland Tribune, figured that nearly 1/12th of all the people who paid to see American League games that season had seen Blue pitch.

“But, I don’t want to sound mushy about this. but I couldn’t have done it by myself,” said Blue. “I got a lot of help from that guy with the handlebar mustache (Rollie Fingers). And Dick Williams really helped. That was his first year as manager, and he taught us how to win. He was tough but fair.”

It started with an otherwise unpleasant off-season, spent in an Army reserve unit. “I was in basic training at Fort Bragg,” said Blue, “and I was in the best shape of my life when I reported to camp that year. I don’t remember what kind of spring I had, but it must have been a good one because I got the opportunity to start the opening game in Washington. That made me the last visiting pitcher to start a Presidential opener, because the next year, the Senators moved to Texas and became the Rangers.”

He won that game, of course, as he won almost all his games in the first half of the season. Oddly, though, the one game he remembers most in that stretch was a loss.

“We came into Boston and there was a huge buildup because I was 9-1 and Sonny Siebert was 10-0,” he said. “Well, I lost the game because I gave up home runs to Rico Petrocelli and Doug Griffin, who didn’t hit much over .240 lifetime but I guarantee you he hit about .475 against me. But it was just such a thrill to me because of all that baseball means in Boston and all the attention we got.”

By the time the All-Star game rolled around, Vida was 17-3, and there was talk that he might even reach the magical 30-win plateau.

The All-Star Game was another thrill, as Blue was the winning pitcher for the American League, even though he gave up a home run to Hank Aaron. “Somebody told me it was Hank’s first extra-base hit in an All-Star game,” Vida said. “You never like to give up a home run, but you don’t feel so bad when it’s Hank Aaron who hits it.”

In the bottom of the third, Reggie Jackson pinch-hit for Blue and hit a home run which everybody remembers, a drive that hit the top of the light standard opposite the right field stands, narrowly missing going out of Tiger Stadium. The ball was hit so hard that it caromed back onto the playing field, to be grabbed by Willie Mays playing center for the National League. “To be honest,” said Blue with deadpan humor, “I don’t think I could have hit the ball that far.”

Playing for the A’s in those days, of course, meant playing for Charlie Finley, and the A’s owner always had to find a way to take at least some of the spotlight away from his stars. His first attempt with Blue was an announcement that he would pay Vida to change his first name to True. It was an outrageous suggestion to Vida, who had been named after his father.

“My dad died when I was only 17,” said Vida, “so I always thought that everything I did was to honor him. I don’t know how much Finley was willing to pay because he never said. I think my response pretty much took care of that idea.”

Then, Finley presented a Cadillac to Blue, which Vida regarded as a mixed blessing. “I don’t think he realized what a putdown that was for a black at the time,” said Vida. “Actually, at that time, Reggie was associated with Doten Pontiac, and that was what I wanted—a Pontiac.

“The Cadillac had a 25-gallon gas tank and it was a real gas guzzler. I told Charlie I couldn’t afford to fill it up with what he was paying me, so he gave me an ARCO gas card. I used to go into the gas stations and if I saw, say, a poor woman with five kids, I’d go over and tell her to use my card to fill up. I didn’t figure it was going to break Charlie, but after that year, he took my card away.”

The second half of ’71 wasn’t as successful for Vida, and the A’s lost three straight to the Baltimore Orioles in the American League Championship Series. Still, it was obvious that the A’s were the coming team in the American League, and it seemed Blue would be a big part of their future success. The A’s did indeed win the next three World Series, but Blue’s path was much rockier.

In the offseason, Blue went in to talk contract with Finley. “I was this young. naive kid from the south. I worked my ass off for him and I thought I deserved it. I just thought I’d get a raise automatically.”

Finley told him, “Vida, I know you won the Cy Young and the MVP, that you had 301 strikeouts, that you were 24-8. You deserve a big raise, but you’re not going to get it.”

“He treated me like a colored boy,” Blue said. “It changed my whole perspective about the game of baseball.”

The contract dispute lasted until May. When he came back, Blue’s attitude and work ethic were changed. “I maybe didn’t take that extra lap I should have to keep in top condition,” he said. “I wasn’t mature enough to realize that people were only going to look at my record. I would be the one who would be blamed.” Vida finished the season 6-10, losing his one World Series start.

After that, Blue got back on course, winning 77 games in the next four seasons as the A’s won two more World Series and three straight divisional titles. But he never quite approached the brilliance of that first great year

“I read somewhere that Al Kaline said he felt sorry for (Seattle shortstop) Alex Rodriguez because he had such a great first year and he’ll never be able to match it. That happened to me. Even though I had a couple of 20-win seasons after that, people always wondered why I didn’t do better. They held me to an impossibly high standard, but then, I did, too. I know now that I was too stubborn. I was throwing 85-90 per cent fastballs in those days. The hitters adjusted but I didn’t do enough adjusting to them. I was probably 26 before I really learned to pitch.”

But Blue knows, as we all do, that he had an outstanding career, winning 209 games, winning All-Star Games for both leagues (he was the National League’s winning pitcher in 1978, while with the Giants), pitching in three World Series. “It was special to be part of those World Series teams,” he said. “That’s something nobody can ever take from me.”

And for one magical year, he reached a level few have ever reached in major league history. “I wish that every player could have one year like that, where he’s at the very top of his game. There’s nothing like it.”

GLENN DICKEY writes for San Francisco Chronicle Sports. Reprinted from A’s Magazine, courtesy of Jim Bloom, Oakland Athletics Baseball Club.