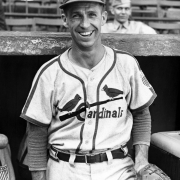

Bob Keely

A big-league career is often a product of fate, luck, and timing. Bob Keely would attest to that. In 1944 the St. Louis Cardinals signed the 34-year-old sandlot star as a third-string catcher. Six months later, Keely was a world champion. Keely was originally signed by the Redbirds in 1936, but a knee injury ended his foray into Organized Baseball after two abbreviated summers. Employed by a tiling company, he continued to play in St. Louis area sandlot and semipro leagues until the Cardinals, whose roster had been depleted by World War II, came calling. With only two ninth-inning appearances and just one big-league at-bat in two years with the Cardinals, Keely’s major-league playing career was short, but it led to a 50-year career in baseball as a respected bullpen coach for the Boston and Milwaukee Braves from 1946 to 1957, and a long career as a scout.

A big-league career is often a product of fate, luck, and timing. Bob Keely would attest to that. In 1944 the St. Louis Cardinals signed the 34-year-old sandlot star as a third-string catcher. Six months later, Keely was a world champion. Keely was originally signed by the Redbirds in 1936, but a knee injury ended his foray into Organized Baseball after two abbreviated summers. Employed by a tiling company, he continued to play in St. Louis area sandlot and semipro leagues until the Cardinals, whose roster had been depleted by World War II, came calling. With only two ninth-inning appearances and just one big-league at-bat in two years with the Cardinals, Keely’s major-league playing career was short, but it led to a 50-year career in baseball as a respected bullpen coach for the Boston and Milwaukee Braves from 1946 to 1957, and a long career as a scout.

Robert William Keely was born on August 22, 1909 on the north side of St. Louis to George and Mary Keely. George, a self-employed house painter originally from Michigan, and Mary were wed in 1907. Her parents were German immigrants who had settled in the Mound City in the 1870s. In their first three years of marriage, the Keelys welcomed three boys into the world: Stanley, and then identical twins Robert and Richard. In 1923 their last child, George, was born. In an era when money was tight, Stanley, Bob, and Richard attended school through the eighth grade, before they dropped out to learn trades and support the family. Bob became a plasterer and laid tile, but his passion was baseball, and he played whenever he could. An attempt to go to night school failed because it meant missing too many baseball games. “We were raised in a baseball family,” said brother George.1 Bob began playing in sandlot leagues and made a name for himself as a good-hitting, strong-armed catcher for teams like the Sunrise Packing Company and Damolay in the local municipal leagues, in the early and mid-1930s. “You’ve got to love baseball —at least I always have. I would have done anything back then to be in baseball. And I’m glad I did. It’s been my whole life,” Keely once said.2

At an age when most men have long since given up on a career in professional baseball, Keely got his chance as a 26-year-old in 1936 when St. Louis Cardinals scout Charley Barrett signed him.3 Unlike many catchers of the era, Keely was tall and lanky (about 6-feet and 170 pounds); he had quick reflexes, and threw and batted right-handed. The Cardinals assigned him to the Springfield (Missouri) Cardinals in the Western Association, one of their 13 Class C teams among 25 farm clubs.4 Keely, a backup to future Cardinals All-Star Walker Cooper, did not play and lasted only a few weeks before he was released.5 He resumed his sandlot career in St. Louis, but was unexpectedly told to report to the Union City (Tennessee) Greyhounds of the Class D Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee (Kitty) League in 1937.6 Keely remained with the team until July; it is unclear if he ever played in a game before a hand injury in July shelved him for the remainder of the season.7

Keely’s minor-league career came to an abrupt close in the offseason. While training at Fairgrounds Park, a municipal park near Sportsman’s Park, the Cardinals’ home ballpark, Keely’s knee locked while he was running downhill. The injury was so severe that the Cardinals’ team physician, Dr. Robert Hyland, performed surgery.8

After convalescing, Keely continued working as a plasterer and tiler and joined a union, but never gave up on baseball. A bachelor who still lived at home with his parents and three siblings, Keely had the luxury of freedom. In the spring of 1939 he signed with Bob Fischer, who ran the Jennings team in the independent Missouri-Illinois League.9 (Jennings is a small city in northern St. Louis County near where the Keelys lived.) In subsequent years he played for the Stags of Belleville, Illinois (across the Mississippi River from St. Louis), in the same league, and regularly garnered praise as the league’s best catcher who had enough talent for him to play Class B baseball.10

World War II had a profound effect on big-league baseball and on Keely. Because of his bad knee, Keely was exempt from military service while hundreds of big-league players were called to serve. Like all teams, the Cardinals suffered a dearth of talent and big-league-ready players.

In a scenario befitting a fairy tale, Cardinals scout Walter Shannon approached Keely after a sandlot game in the spring of 1944 and asked the 34-year-old if he wanted to catch for the Redbirds. The team’s third-string catcher from the previous season, 30-year-old Sam Narron, had retired, and the club needed a bullpen catcher. Keely, who was making about $450 per month for a tile company, told his parents about his second chance at professional baseball. “They said they didn’t like the idea,” remembered Keely, whose salary for the Cardinals in 1944 was $265 per month.11 “But I loved baseball, and my dad could see that. He said, ‘I won’t stop you, because I don’t want you looking back stating that I kept you from finding out what you could do’.”12

On the roster for the entire season, Keely was more like a coach than an active player. He threw batting practice, served as bullpen catcher, and most importantly ran the day-to-day operations in the bullpen. Keely was one of the oldest members of the team, but in a time-honored tradition in baseball, he shaved seven years from his age. For the rest of his major-league career, 1916 was given as his birth date in publications and even on his only Topps baseball card (1954). Keely quickly gained manager Billy Southworth’s trust. He was charged with warming up relief pitchers but also had the discretion to decide which pitchers were best suited in certain situations and games.

It was a dream come true for Keely to play on the eventual World Series champions. His locker was next to that of another player whose career was revived because of the wartime shortage of players, Pepper Martin, Keely’s hero from the 1934 World Series. “We had Walker Cooper and Ken O’Dea, two great ones, so I wasn’t going to get much of a chance [to play],” said Keely.13 On July 25, 1944, Keely made his only appearance of the season under unusual circumstances. With two outs in the ninth inning against the Phillies at Shibe Park in Philadelphia, Cooper went to the mound to confer with his pitcher, Al Jurisich, who was just one strike away from a shutout. Home-plate umpire Jocko Conlan, who had warned Cooper to speed up, ejected him in a 9-0 game, leaving the Cardinals in a predicament. O’Dea was tending to his sick wife at home; Keely was the last and only option. He suited up and caught two pitches —a ball and then a third strike to complete Jurisich’s shutout.14 Keely was on the World Series roster, pitched batting practice, and was one of 21 players to receive a full share of World Series winnings. “[Keely] earned his share,” wrote The Sporting News, “by catching thousands of deliveries in the Cardinals bullpen and warming up pitchers for that 105-game winner.”15

In 1945 Keely reported early to the Cardinals’ spring training site in Cairo, Illinois, and it appeared as if he would transition into a full-time bullpen coach.16 In addition to Cooper and O’Dea, the Cardinals had highly touted rookie Del Rice in camp. But when Cooper was called into military service in late April, Keely was added to the active roster.17 Serving as the bullpen catcher for his second and final season in the big leagues, he played just one inning the entire season, in the next-to-last game of the year, when he replaced Rice in a game against the Reds in Cincinnati. In the top of the ninth inning he made an out in his only big-league at-bat. He caught the final inning of Glenn Gardner’s complete-game, 6-2 victory. The Cardinals finished in second place and released both the 35-year-old Keely and manager Southworth in the offseason.

During their two years together in St. Louis, Southworth and Keely had established mutual trust and respect. When Southworth was named skipper of the Boston Braves for 1946, he invited Keely to spring training in Bradenton, Florida.18 “Billy Southworth made me feel like one of the greatest guys he ever had work for him,” said Keely.19 When the team broke camp and headed for Boston, Keely was the fourth catcher, behind Phil Masi, Stew Hofferth, and Hugh Poland.20 Before the season began, he was named bullpen coach, and his playing career was over.

Keely served as a respected bullpen coach for the Braves in Boston and Milwaukee from 1946 until his unexpected retirement in March 1958. Often described as “quiet,” “tireless,” and “always busy,” Keely had a reputation as a patient, astute observer, whose dedication to his pitchers was praised.21 After winning 20 games in 1946, his first full season, Johnny Sain gave credit to Keely. “There’s something that fans and writers didn’t realize about me last season. It was the help given me by Bob Keely. Some catchers, in warming up pitchers, look around the stands to see if they can spot some friends. Some like to rib and heckle rival players. But not Keely. The guy really instills confidence into the pitchers.”22

Keely was especially good at developing young players and was considered “one of the finest characters in baseball.”23 When the Braves signed 18-year-old phenom Johnny Antonelli for a reported $75,000 bonus prior to 1948 season, Keely was part of the club’s contract negotiating team. Life magazine even reported how Keely, a nondrinker and nonsmoker, was charged with “making Johnny a major-leaguer.”24 They roomed together on the road. Over the course of his coaching career, the soft-spoken, shy Keely, with his gleaming blue eyes, was praised for being a father figure to many of his team’s rookies and youngsters.

Opposing managers also recognized Keely’s expert handing of the bullpen and pitchers, and twice named him to the NL staff for the All-Star Game. The Braves’ Southworth named his trusted coach the batting practice catcher of the 1949 squad,25 but a bigger honor may have come in 1955 when Leo Durocher, skipper of the New York Giants, named him bullpen catcher for the game in Milwaukee. The recognition was not lost on Lloyd Larson, a sportswriter for the Milwaukee Sentinel. “It’s a well-deserved award for a swell guy —a hard worker. From opening day of spring training until the season closes, invariably [Keely’s] the first man on the field and the last to leave.”26 A player’s player, Keely was an ultimate hustler.

In his 12th and final season as a Braves coach, Keely experienced the pinnacle of team success when Milwaukee defeated the New York Yankees in the 1957 World Series. In a startling move just weeks after the season, the Braves fired three of their four coaches (Johnny Riddle, Charlie Root, and Connie Ryan). Asked why he was not included in the axing, Keely responded, “I guess I was too busy minding my own business,” a response that pointed to the acrimonious relationship between Ryan and manager Fred Haney and the anger and outrage expressed by Root over his termination.27 The following spring Keely abruptly resigned. In an open letter to general manager John Quinn, he cited his poor health as the reason for his decision, but also noted, “Money has not been a factor in this matter, nor has anything between me and anyone on the club.”28 The latter remark helped fuel speculation that Keely and Haney no longer saw eye-to-eye.

Keely moved to the Bradenton-Sarasota area in 1960 and became a scout for the St. Louis Cardinals, a job he held until he retired 1978. Keely’s twin brother, Richard, was a longtime scout for the Braves. Just as he was during his playing and coaching career, Keely exhibited an unwavering desire and commitment to baseball. “I never tire of baseball,” he said of his typical 11-hour days scouting. “I’m the first one [at the park] and if I leave early, it’s probably to go see another game at another park. I don’t get excited until I see a kid six, eight, or maybe 10 times.”29

Keely never strayed far from baseball even in retirement. He scouted into his 80s for the Los Angeles Dodgers in the Gulf Coast League and assisted the Pittsburgh Pirates at their spring training site in his home town of Bradenton.30 “I started my career with a World Series championship team, the 1944 Cardinals, and ended with one, the ’57 Braves,” Keely said, noting that he had never been on a losing team.31

Frail, suffering from the onset of dementia, and living in an assisted-living center the last few years of his life, Bob Keely died at the age of 91 on May 20, 2001, in Sarasota, Florida. Always modest, he often pointed out how lucky and fortunate he was to have the career he enjoyed. “The war gave me a great opportunity,” he said, “because I got to work in the big leagues.”32 Upon hearing the news of Keely’s passing former Braves pitcher Ernie Johnson remembered Keely as “a hard worker and totally respected by the pitching staff.”33

Sources

Books

Andrews, Tom, and Rich Wolfe, For Milwaukee Braves Fans Only (Covington, Kentucky: Clerisy Press, 2011).

Buege, Bob, Eddie Mathews and the National Pastime (Milwaukee: Douglas American Sports Publications, 1994).

Buege, Bob, The Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy (Milwaukee: Douglas American Sports Publications, 1988).

Caruso, Gary, The Braves Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995).

Klima, John, Bushville Wins (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2012).

Mumau, Thad, An Indian Summer: The 1957 Milwaukee Braves, Champions of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007).

Povletich, William, Milwaukee Braves: Heroes and Heartbreak (Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2009).

Newspapers

Chicago Tribune

Milwaukee Journal

Milwaukee Sentinel

New York Times

Online Sources

Ancestry.com

Baseball-Almanac.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Notes

1 Harold M. Unger, “He had one big league at-bat, but a long career,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, May 29, 2001, 1A.

2 Mike Eisenbath, “Playing for love, not for money; In ’44 Keely couldn’t resist Cards’ offer,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 29, 1994, 5C.

3 Jim Sandoval, “Charley Barrett, The King of Weeds,” in Jim Sandoval and Bill Nowlin, eds., Can He Play? A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2011), 11.

4 “Springfield to Try Sandlot Graduate,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1936, 2.

5 Eisenbath.

6 Janet Gibson, “Keely was a baseball player, coach, scout,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, May 22, 2001, 6B.

7 Eisenbath.

8 Eisenbath.

9 The Sporting News, April 20, 1939.

10 “Krepel Names ‘Three Eye’ League From Illinois-Missouri,” Alton (Illinois) Evening Telegraph, December 21, 1940, 1.

11 Eisenbath.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Associated Press, “Bob Keely Nearly in Ball Game,” Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland), September 13, 1945, 10.

15 The Sporting News, April 26, 1945, 5.

16 Associated Press, “Flood Waters Keep Cards From Starting Practice,” Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland), March 20, 1945, 7.

17 Associated Press, “O’Dea Gets Chance with Cooper Gone,” Ottawa (Ontario) Citizen, April 24, 1945, 14.

18 The Sporting News, March 21, 1946, 10.

19 Eisenbath.

20 The Sporting News, April 11, 1946, 8.

21 The Sporting News, April 11, 1956, 13.

22 The Sporting News, February, 19, 1947, 11.

23 The Sporting News, July 7, 1948, 6.

24 “Spring Training: The Boston Braves Have a Congenial Camp,” Life, March 28, 1948, 108.

25 New York Times, July 7, 1949, 32.

26 Lloyd Larson, “Durocher Did All Right for Braves in All-Star Selection,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 6, 1955, 2.

27 Bob Wolf, “Fred’s Coaches Are Angry,” Milwaukee Journal, November 5, 1957, 18.

28 The Sporting News, March 19, 1957, 27.

29 John Brockman, “Baseball Scouts Devoted to Complex Job,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, June 6, 1971, 9B.

30 Eisenbath.

31 John Brockman, “Bob Keely Looms Top Cardinal Fan,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, October 10, 1964, 14.

32 Eisenbath.

33 Unger.

Full Name

Robert William Keely

Born

August 22, 1909 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

May 20, 2001 at Sarasota, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.