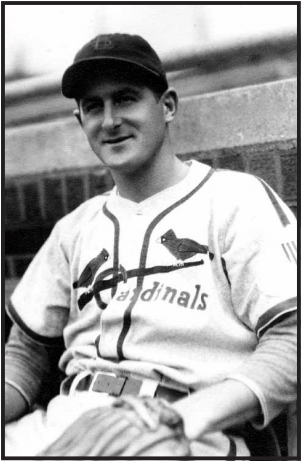

Gene Crumling

Gene Crumling always envisioned himself as a baseball player. “He dropped the ‘b’ from his name when he started playing professional baseball because he said it looked better in print. Our folks didn’t mind,” said his brother Bill.1 Crumbling turned into Crumling in 1941 when Gene kicked off his 12-year professional-baseball career, spent primarily in the low minor leagues, as a fine-fielding but weak-hitting catcher. Four years later, with major-league rosters depleted by World War II, Crumling got his chance as a late-season call-up by the St. Louis Cardinals in 1945. He played in six games, including three starts, and recorded one hit in 12 at-bats in a big-league career that spanned a mere three weeks during the Cardinals’ tense pennant race with the Chicago Cubs that September. The following season, Crumling was back in the low minors.

Eugene Leon Crumling was born on April 5, 1922, in Wrightsville, a small, historic town nestled along the Susquehanna River in south-central Pennsylvania, about 30 miles from the Maryland border. His parents, William H. and Elma Grace (Dietz) Crumbling, were hard-working, industrious folks born in the Keystone State. With moderate means they raised eight children (seven boys and a girl born between 1908 and 1927) and another one from William’s first marriage. William toiled his whole life in construction while Elma found piecemeal work to support the family. Gene, the third youngest in the family, was a natural athlete. He played basketball and ran track at Wrightsville High School, whose foundation his father had laid with a team of horses and a scoop. However, Crumling left his mark as a rocket-armed catcher on the baseball diamond. By the time he was 14 years old he was playing on local sandlots and town teams, moving on to semipro leagues in nearby York, Hallam, and Mount Joy as the Great Depression gradually loosened its grip on American society. The right-hander had a peculiar nickname: Lefty. “As a young kid Gene always did things with his left hand, threw a baseball with his left hand,” explained Bill Crumbling. “He got the name Lefty and it stuck with him even though he switched over doing things right-handed.” After Gene graduated from high school in 1940, he began working construction with his father, but continued playing ball whenever he could. “He loved baseball,” Bill remembered. “He always liked playing for teams in small towns all over the area. There were teams everywhere; there wasn’t much else to do.”

Drawing interest from both the St. Louis Browns and Detroit Tigers, Crumling signed in 1941 with Fred “Dutch” Dorman, player-manager with the Hagerstown (Maryland) Owls, the Tigers’ affiliate in the inaugural season of the Class B Interstate League. “My father always said that he played for the fun of it and not for the money,” said Gene’s only child, Joe Crumling. “He never earned much, but he was a dedicated to the sport.”2 With a $100-a-month contract he fulfilled his dream. Only 19 years old, Crumling opened his professional baseball career as an understudy, catching in 28 games while learning the ropes against older and more experienced players.

Crumling recorded only 18 hits in 100 at-bats in 1941, but his biggest hit did not show up in the box score. On August 7 he married Lillian Whitehead of Hagerstown. According to his family, Crumling met his future wife while she and her parents were at an Owls game. The wedding ceremony was held in front of the entire baseball team.3 The following year their only child, Joe, was born.

After batting .208 in 47 games for the Owls’ first-place squad in 1942, Crumling was sold in midseason 1943 to the Allentown (Pennsylvania) Wings, the Cardinals affiliate in the Interstate League. The Cardinals farm system had a radically different look in 1943 than just a year earlier. Following the departure of GM Branch Rickey after the ’42 season, the club reduced its number of minor-league affiliates from 22 to eight in just one year. The move was necessitated by World War II, which had thinned rosters throughout Organized Baseball.

Crumling had all the tools of an excellent defensive catcher. He was an even 6 feet tall, weighed 180 pounds, and was blessed with quick instincts. According to the Morning Herald of Hagerstown, Maryland, Crumling “has a fine arm and does not hesitate to take a shot at the runners, and he is tops in taking in foul hoists.”4 Teammates and newspapers often called him Rags, a tribute to his rough-and-tumble and aggressive play.5

“Gene could be a hot-head and had a temper,” his brother Bill noted. “I saw him get thrown out of a few games, too. I remember him once yelling at an umpire and kicking dirt on him at a game in nearby Lancaster, in the old Interstate League. Well, he got kicked out maybe in the first inning and met me outside of the park. We went drinking at a local bar afterward.”

After proving that he could hit well enough to be taken seriously (.258 in 310 at-bats) in his third year of pro ball, Crumling earned a promotion to the three-time reigning Junior World Series champion Columbus (Ohio) Red Birds of the American Association in 1944. Like most teams in the league, Columbus consisted of prospects on their way up to the big leagues and former big leaguers struggling to hold on to the love of their life. Crumling, the Red Birds’ third-string catcher, batted a respectable .256 in 125 at-bats and provided excellent fielding in 37 games.

After playing in only 13 games for Columbus in 1945, Crumling left the team in May over a dispute when club officials refused to let him go home to tend to his ailing father, who ultimately died that summer.6 Crumling was transferred to the Rochester (New York) Red Wings of the International League later that season. One of five catchers on manager Burleigh Grimes’s team, Crumling batted .257 in 113 at-bats with little power, but continued his excellent fielding, easily leading the brigade of catchers with a .985 fielding percentage.

The catcher’s position proved to be a challenge for the three-time reigning NL-pennant-winning St. Louis Cardinals in 1945. Three-time All-Star Walker Cooper went into the service after playing in just four games in April. Dependable backup Ken O’Dea was pushed into regular service and appeared in a career-best 100 games before a sore back sidelined him after September 6, leaving the team with just one active catcher, 22-year-old rookie Del Rice. In a worst-case scenario, the Cardinals also had 35-year-old Bob Keely on the active roster; however, he was the team’s bullpen catcher and played in only one inning all season. Consequently, club owner Sam Breadon bought Crumling’s contract. Crumling had joined the precursor to the Army Reserve before Pearl Harbor; however he was subsequently classified 4-F (medically unfit) because of a hernia and never saw active duty.7 [After the 1948 season, he had an operation to correct the hernia].

“I just went limp,” said Crumling upon learning the news of his promotion. “I packed up and headed for St. Louis the next day.”8 On September 11, two days after his arrival, Crumling debuted at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis when he replaced Rice and caught the last two frames in a 6-5 victory against the New York Giants. Thrust into a tight pennant race with the upstart Chicago Cubs, Crumling made his first start in a loss to the Philadelphia Phillies in the first game of a doubleheader on September 16. He notched his only big-league hit and knocked in his only run the following day against the Phillies. As reported by the Associated Press, Crumling executed a squeeze bunt, driving in a run in the Cardinals’ five-run third inning.9 In interviews well after his playing days, Crumling preferred speaking about his first hit: it was a line-drive single off slugger Jimmie Foxx, who was pitching for the ninth and final time in his last season in the big leagues.10 In his six-game career, Crumling handled 20 chances without an error (16 putouts and 4 assists) and recorded one hit and one RBI in 14 plate appearances (including two sacrifice hits).

The Cardinals anticipated a surfeit of catchers in 1946. Veteran Walker Cooper as well as prospects Joe Garagiola, Del Wilber, and Jerry Burmeister were expected to return stateside following completion of their military service; Rice and O’Dea were holdovers from the ’45 squad. With so many bona-fide big-league catchers, the Cardinals sold Crumling in the offseason to Rochester, where he joined nine other catchers on the team’s active list.11 Rochester released Crumling before he had a chance to don the tools of ignorance for them. He supposedly turned down Triple-A contracts with the Jersey City Giants of the International League and the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association in order to sign with Hagerstown, which he had called home since 1941.12

Once described as the “mainstay” of the team, Crumling was a popular fixture with the Hagerstown Owls over the next four years (1946-1949).13 Never much of a hitter, Crumling batted .216, .240, and .216 (averaging about 290 at-bats and 95 games per season), before experiencing a surge in his career year in 1949. For a last-place team (49-89), he hit .282, almost 50 points higher than his career average, while also setting career highs in hits (110) and games (118). The Daily Mail of Hagerstown considered him “one of the finest receivers in the game.”14

Upon his return to the Owls, Crumling expressed to owner Owen Sterling his desire to transition to managing. When Pep Rambert, with two years of managing experience, was named skipper for the ’48 season, Crumling threatened to quit baseball, and joined a semipro team in Washington County, for which Hagerstown is the county seat.15 Ultimately lured back to the team, Crumling took the reins of the club on May 27 when Rembert unexpectedly resigned. The toll of managing a woefully talent-poor team and catching regularly proved to be too much for the 26-year-old. By the end of June Crumling was replaced as skipper by Benny Culp.

The faithful fans of the Hagerstown Owls saw Crumling as one of their own: a local, hard-working guy struggling like the rest of them to make ends meet while offering them a few hours’ respite from the doldrums of everyday life. A month after he was fired, the fans staged a Gene Crumling appreciation night at Municipal Stadium.16 He was showered with gifts including a rifle, a shotgun, and even a race horse. “Gene didn’t know what to do with a race horse,” his brother said, laughing. “He didn’t even go to the races, so he got rid of it.”

Crumling’s association with the Owls ended in early 1950 when Sterling sold the team to Gene Raney, who signed an affiliation agreement with the Boston Braves and turned over the roster. “Genial Gene” (so named for his likeable personality) was released.17

Crumling remained in baseball for three more years (1950-1952), hoping to parlay his knowledge of the game into a permanent coaching career. After playing for the Sunbury (Pennsylvania) A’s in the Interstate League in 1950, he was one of three different managers who guided the York (Pennsylvania) White Roses to a 51-88 record in the Interstate League the following season. His final shot at managing came with yet another weak team, the Wellsville (New York) Rockets of the Class D Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York (PONY) League. He was fired less than two months into the Rockets’ last-place season. Crumling returned home and finished out the year with York, for whom he batted just .174 in 34 games.

Only 30 years old, Crumling hung up his spikes after a 12-year career in professional baseball. Forever thereafter, Crumling could call himself an ex-big leaguer who also played in 895 minor-league contests.

After his playing days, Crumling returned to Wrightsville, where he and his wife, Lillian, lived for the rest of their lives. Like many in central Pennsylvania, Crumling was an avid outdoorsman, and had a fierce independent streak. “After baseball, the love of his life was hunting,” said Joe Crumling, who offered a story to illustrate his point. “My dad had a job at Bendix Aviation in York, but wanted to go hunting with his friends up in Potter County where they had a lodge. His boss told him he couldn’t go because he didn’t have any vacation. So he quit, and never worked in a factory again.”

Crumling’s primary occupation after baseball was bartending, which he did for 15 years at the Washington House restaurant in Wrightsville and then for 27 years at the Kreutz Creek Valley VFW hall. Though his formal bonds to Organized Baseball quickly dissipated after his retirement, he remained lifelong friends with a number of ex-big leaguers from Pennsylvania, such as Kenny Raffensberger, a 15-year veteran from York, All-Star third baseman Whitey Kurowski of the Cardinals, and Nellie Fox, a central Pennsylvanian who played in the Interstate League in the mid-1940s.

Talkative yet modest about his career in baseball, Crumling graciously signed autographs for fans looking for the “one-hit wonder” who had a cup of coffee with the Cardinals in 1945. In 1995 he was elected to the York Sports Hall of Fame, joining his friend Raffensberger and the man who signed him to his first professional contact, Dutch Dorman. In 2008 Crumling threw out the ceremonial first pitch in the first playoff game for the York Revolution, an independent team,

“My dad was a tough old bird,” said son Joe. In his later years, Crumling overcame both prostate and colon cancer. He died at the age of 89 on February 11, 2012, in Yorkana, about five miles from Wrightsville. He was preceded in death by wife of 56 years, Lillian, who died of emphysema in 1997. They are buried in Highmount Cemetery in Hallam.

Sources

Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail

Hagerstown (Maryland) Morning Herald

The Sporting News

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.com

SABR.org

The author interviewed Bill Crumbling (player’s brother) on February 22, 2014.

The author interviewed Joe Crumbling (player’s son) on February 22, 2014.

Notes

1 Author’s Interview with Bill Crumbling on February 22, 2014. All quotations from Bill Crumbling are from this interview.

2 Author’s Interview with Joe Crumling on February 22, 2014. All quotations from Joe Crumling are from this interview.

3 “Miss Whiteman Wed To Baseball Player,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail, August 8, 1941, 6.

4 “The Colley See Um,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Morning Herald July 19, 1946, 3.

5 The Sporting News, August 23, 1945, 20.

6 The Sporting News, May 31, 1945, 18.

7 Crumling’s brother Bill was not sure when Gene joined the Reserve. He knew it was before the attack on Pearl Harbor and could have been as early as 1940.

8 Frank Bodani, Link to Baseball’s Past,” York (Pennsylvania) Daily Record, October 5, 2008.

9 Associated Press, “7-3 Wins Boosts Cards to Within 3 Games of Top,” Williamsport (Pennsylvania) Sun-Gazette, September 18, 1945, 4.

10 Frank Bodani, Link to Baseball’s Past,” York Daily Record, October 5, 2008.

11 Associated Press, “Crumling of Cards Goes to Rochester,” Dunkirk (New York) Observer, February 15, 1946, 12.

12 “Know Your Owls … Introducing Gene Crumling,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail, May 16, 1946, 16.

13 “Owls Catching Staff Boosted,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail, January 21, 1947, 13.

14 Dick Kelly, “Kelly’s Sport Column,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail, August 3, 1946, 8.

15 Dick Kelly, “The Spotlight on Sports,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail, April 10, 1948, 8.

16 The Sporting News, August 4, 1948, 33.

17 Dick Kelly, “The Spotlight on Sports,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail, August 25, 1949, 24.

Full Name

Eugene Leon Crumling

Born

April 5, 1922 at Wrightsville, PA (USA)

Died

February 11, 2012 at Yorkana, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.