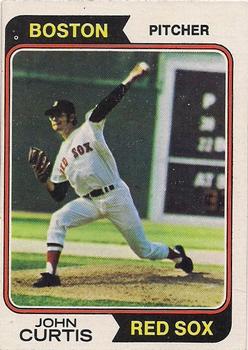

John Curtis

Starting in 1970, John Curtis played in the major leagues for 15 years. He was a respectable left-handed pitcher — 89 wins and 97 losses, with a lifetime ERA of 3.96 — praised as much for his eloquence as his fastball.

Starting in 1970, John Curtis played in the major leagues for 15 years. He was a respectable left-handed pitcher — 89 wins and 97 losses, with a lifetime ERA of 3.96 — praised as much for his eloquence as his fastball.

John Duffield Curtis II was born March 9, 1948 in Newton, Massachusetts, the second son of George and Anne (Tafel) Curtis. Although he was too young to remember, he spent the first three years of his life at 165 Concord Street, Newton Lower Falls, in a house with a back yard alongside the meandering curve of the Charles River. His father was a reservations manager for American Airlines and was transferred from Boston’s Logan Airport to LaGuardia Airport in New York City.

He does recall his childhood at Great Neck, New York, very near LaGuardia. There his family lived in an apartment building that provided a grassy play area nearby where his father would play catch with him and his older brother Bill. George Curtis had been a pitcher while at Andover Prep as well as playing three years on the Yale baseball team. John II recalled, “I learned much later on from an old teammate of his that Dad had a pretty good curve ball. He taught us how to throw one, along with how to catch it.”1

After mastering those first lessons, his father took Bill and John to nearby Gabler Field in Great Neck, and started working on hitting and catching fly balls. The brothers then took their early baseball education to the streets and joined in the neighborhood games of stickball and stoop ball, Wiffle ball, and anything else that would accommodate a bat and ball. John Curtis’ first introduction to organized baseball games came to him by way of Great Neck’s Police Athletic League before he reached age 10.

At the age of 8, Curtis was also inspired after watching one of baseball’s greatest players.

“Young fans found in [Willie] Mays a role model for their own aspirations. Most kids don’t make it to the majors, but John Curtis did, and his dreams began when he walked into the Polo Grounds as a small boy from Long Island. Sitting in the upper deck, he saw ‘that expansive green grass field and the perfect symmetry of the (diamond) — it was like seeing Oz for the first time.’ He watched in awe as the players took their warm-ups, ‘aghast’ that even a pop fly, appearing so easy to handle on television, required so much skill and judgment to actually catch. And then Mays came out, and everything he did looked so easy. Loping across the field to catch fly balls. Throwing perfect strikes to home plate from three hundred feet. Spraying line drives to all parts of the ballpark. ‘And during the game,’ Curtis recalled, ‘he was so colorful and so full of energy. He just seemed at that moment to symbolize what that whole game was about. The harnessing of immense talent. And from that moment on, I knew that was what I wanted to do. If I was going to grow into a baseball player, I wanted to be someone with the authority and grace of Willie.’”2

Shortly after seeing Mays, John’s third-grade teacher asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up. He said with true conviction that he wanted to be a baseball player. He wanted to be like Willie. “How ironic that I ended up being a pitcher,” he said. “I swear, if there’s another life, I’m coming back as a center fielder!”3

In 1957, the Curtis family moved to Smithtown, New York, also on Long Island but further out, in Suffolk County. His solid foundation in baseball, which had begun with his father, continued in organized youth baseball. He joined the local Little League team, graduated to the Babe Ruth League, and finally to the Connie Mack league at the same time he was on the junior and senior high school teams.

Curtis attended Smithtown High School, graduated in 1966, and was first drafted by the Cleveland Indians in the first round of the 1966 major-league baseball draft. He did not sign, instead opting to attend Clemson University. Scouts continued to follow his progress and were impressed with his performance on the mound, which included three no-hitters and a perfect game. In the 1967 Pan American Games he became the first American to defeat Cuba in national competition.4

As a youth, Curtis was an avid reader of baseball books and became aware of the rich history of baseball by way of print and film. He recalled several old classics such as The Babe Ruth Story and Pride of the Yankees. His favorite book was Veeck as in Wreck, the Bill Veeck memoir co-authored with Ed Linn. Reaching further back in baseball history, he said he was introduced to Ring Lardner and his You Know Me, Al stories by his 17th-century English literature professor at Clemson.5

Curtis, 6-foot-1 and listed at 175 pounds, became the first-round Red Sox pick in the 1968 draft. The left-hander was assigned to Winston-Salem of the Carolina League, where he pitched creditably but not spectacularly. That concerned Boston enough to keep him in Single-A ball in 1969. He was transferred to Greenville of the Western Carolinas League, where he improved and developed an impressive fastball. But there were still concerns. He walked 97 batters and his ERA grew to nearly 4.50, losing 12 of 18 decisions. His time in the minors also increased, but at least he was getting closer to Boston when he was moved to Double-A Pawtucket in 1970. He improved his control, repaired his ERA, and made enough progress that the Red Sox called him up in mid-August 1970 and put him in the bullpen.

A ballplayer’s debut is always memorable even if that is so only for the player himself. Sometimes it is memorable for other reasons, and not for being a moment of triumph, but for a moment that is humbling that knocks him off the mound and sends him tumbling down. That Sunday, August 13, 1970 would become a day to un-remember. Yet Curtis ought not to have carried the full burden of blame. After all, Clif Keane of the Boston Globe granted, “whatever ails the rest of the Red Sox pitching staff got to the lefthander who was brought up from Pawtucket for his first try against the Royals.”6

In the seventh inning, with the bases loaded, Curtis served up a pitch to left-handed Royals catcher Ed Kirkpatrick that was sent to Fenway oblivion, a grand slam that surprised the batter as well when he realized that Curtis was making his major league debut. “I didn’t know if the ball was going to make it over the Red Sox bullpen with the wind blowing in,” said Kirkpatrick.7 Asked if he would like to have the grand slam ball as a permanent memento, Kirkpatrick flashed a smile and held up a ball. “This is the ball I hit. Somebody in the Red Sox bullpen picked up the ball and tossed it to Dave Morehead in our bullpen.”8 John Curtis would have wished to have not the ball, but that pitch, back.

Curtis did not pitch again in Boston in 1970. He was sent back to Pawtucket and started the 1971 season in Louisville. When he did finally wear a Boston uniform again, in September 1971, manager Eddie Kasko decided to use him as a starter. Curtis lost the first two games and then, coming out of the bullpen, recorded his first major-league win against the Cleveland Indians. His final appearance on the mound in 1971 was a complete game victory over the Washington Senators. Five game appearances, two wins, and two losses was his final tally for the year.

Although he began the 1972 season with the Triple-A Louisville Colonels, he returned to Boston in May. He got more game opportunities and proved worthy of them, posting a 3.73 ERA to go with an 11-8 record.

At the end of the 1972 season, Curtis became the answer to a trivia question. The new designated hitter rule would go into effect in 1973, and on September 28, 1972, Curtis became the last pitcher to ever bat in a regular lineup at Fenway Park, in the bottom of the seventh inning, in a 3-1 Red Sox win over the Kansas City Royals.

He connection to Boston would prove to be enduring. Curtis began writing as a sideline interest. The Boston Globe featured the Red Sox player — now an emerging writer tossing words instead of pitches — in an article published on October 8, 1972:

“John Duffield Curtis II just completed a very successful rookie season as a Red Sox pitcher. But then, if anyone was born to be a Red Sox, it was Curtis, whose great uncle laid the original sod in Fenway Park and whose uncle was Tom Yawkey’s Yale roommate. And, if any Boston player should write, it is Curtis, who in the off-season writes for the Spartansburg, S.C., Herald while taking graduate courses.”9

In the article he wrote that the 1972 season “will be most remembered as the year of the strike. The baseball strike that delayed opening day for almost two weeks was an exercise in confusion and selfish indifference. I am not sure the accomplishments can bear the weight of public opinion. If a lesson can be derived from the experience, it should be that player-management disagreements cannot abuse the public interest. The fans are the crux of baseball. Without them, there is no need to discuss pension funding.”10

Though Curtis was 13-13 with an ERA of 3.58, manager Kasko’s 1973 season did not turn out as well as he and others hoped. He was fired, much to the dismay of many of the players who praised him for the opportunities he gave them. John Curtis was vocal about his opinion of Kasko’s end. He told Peter Gammons. “I feel really badly about Eddie. He’s a man who gave me 50 starts in the big leagues right off. He’s a man who’d stick with me. We are the ones who let him down. I can’t look at this season and say we gave it our best shot. I thought we could win it, and as a team I think we have to look back and say we didn’t do what we should have. But as it has happened, I’d have to say I’m not unhappy at who is coming up. As you know, I have great respect for Darrell [Johnson. He got me here. He turned my entire career around and got me to be able to answer things for myself.”11 Reporters were finding Curtis a useful resource as an interview.

Eddie Kasko was not the only person exiting Boston at the end of the 1973 season. Curtis, along with Mike Garman and Lynn McGlothen, was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals for Reggie Cleveland, Terry Hughes, and Diego Segui.

Curtis was with the Cardinals from 1974 to the end of the 1976 season, appearing mostly as a starter. In 1977, he was traded to the San Francisco Giants and was utilized much more as a reliever. During his three years with the Giants, he started 27 games and came out of the pen in 89.

Curtis continued the West Coast years of his baseball career by signing with the San Diego Padres as a free agent. By the end of the1980 season, he found himself the ace of the staff, with a 10-8 record and a 3.51 average. Although he began the strike-shortened 1981 season as a starter, he ended up in the now familiar role as a reliever during the last half of the season. His contract was purchased by the California Angels in August 1982, and he remained with the team until he retired after the 1984 season.

Upon retiring, Curtis considered what he might do next. He had always been an intelligent, insightful interview, sought out by reporters looking for an approachable player who provided useful material for their columns. It was a natural fit for him. He began writing articles for the San Diego Union-Tribune, Boston Globe, San Francisco Chronicle, and Sports Illustrated. He wrote articles for the San Francisco Examiner during the offseason, 1977 to 1979, and was given the freedom to write about whatever he wanted. He later reviewed books on baseball and other sports for the San Diego Union-Tribune. He also wrote a biography of sportswriter Ed Linn for the Dictionary of Literary Biography in 2005.

“I did write an article for the Boston Globe at the end of the ’71 or ’72 season. I don’t remember much about it. I was also asked to write a piece for the Christian Science Monitor around that time, and I turned in something that explained how a starting pitcher was like an artist looking at a blank canvas. It was strictly amateur, but the writing did inspire me to look for a sportswriting job in the off-season. In 1971, I wrote for the Spartanburg (South Carolina) Herald-Journal. I discovered that writing for a daily newspaper was a lot like my baseball job. In both, you had to put in a lot of hours at night.”12

Curtis returned to the field in 2005 as a pitching coach for the Long Beach Breakers of the independent Western Baseball League. He saw the chance the give back to the game some of the great things it gave to him.13

As of 2018, John Curtis and his wife Mary Ann reside in Charleston, West Virginia. He continues to write and maintains an interest in baseball, in particular regarding young players advancing through the minors, as he had, to the major-league level.

“I took a crack at writing on baseball and I fell far short of where I hoped I’d land. My inspiration to write came from the beat writers I encountered in Boston, among them Peter Gammons, Ray Fitzgerald, and Clif Keane. There was also a gentleman by the name of Roger Angell, who entered my life while I was pitching for the Red Sox. After reading The Summer Game, he became my Willie Mays of writers.”14

Last revised: August 9, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and verified for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Notes

1 Correspondence with John Curtis, July 19, 2010.

2 James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, the Legend (New York: Scribner, 2010), 258.

3 Correspondence with John Curtis, September 10, 2010.

4 Bruce Markusen, “The Hardball Times,” March 24, 2014.

5 Ibid.

6 Clif Keane, “K.C. Rips Sox, 11-3,” Boston Globe, August 14, 1970: 21.

7 Neil Singelais, “Yesterday: A Hit Tune Sox Would Like to Forget,” Boston Globe, August 14, 1970: 22.

8 Ibid.

9 “Curtis Writes: Sox Locker Room Silence Proved Big Point,” Boston Globe, October 8, 1972: 76.

10 Ibid.

11 Peter Gammons, “Sox Players Sorry Kasko Gone,” Boston Globe, October 1, 1973: 23.

12 Correspondence with John Curtis, July 19, 2010.

13 http://www.baseballsavvy.com/archive/w_johncurtis3.html

14 Correspondence with John Curtis, September 10, 2010.

Full Name

John Duffield Curtis

Born

March 9, 1948 at Newton, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.